The Threatened Legacy of Baltimore's Brutalist and Urban

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ED 022 658 RE 001 449 By-Cooper, Minna; and Others DEVELOPMENTAL READING in SOCIAL STUDIES; the LOCAL COKMUNITY: LONG ISLAND and NEW YORK CITY

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 022 658 RE 001 449 By-Cooper, Minna; And Others DEVELOPMENTAL READING IN SOCIAL STUDIES; THE LOCAL COKMUNITY: LONG ISLAND AND NEW YORK CITY. A GUIDE FOR TEACHERS, GRADE 7, REVISED. Sewannaka Central High School District Number 2, Nassau County, N.Y. Pub Date 64 Note-63p. EDRS Price MF-S0.50 HC-$2.60 Descriptors-COMPREHENSION, CONTENT READING. CRITICAL THINKING, *CURRICULUM GUIDES. *DEWLOPMENTAL READING. DIRECTED READING ACTIVITY, *GRADE 7, *SOCIAL STUDIES. STUDY SKILLS. VOCABULARY DEVELOPMENT This guide is designed to provide seventh-grade social studies teachers with materials needed to present instruction in reading skills and to teach those facts, concepts, and attitudes which are the aim of social studies education.Entries on the subject of Long Island and New York City are arranged by topic, and material within each topic is arranged according to two texts: "Living in New York- by Flierl and Ike to be used with modified classes, and 'New York: The Empire State byEllis. Frost, and Fink, to be used with honors and average classes. To promote the development of comprehension, vocabulary, criticalthinking, and studyskills,the guide presents exercises in categorizing, reading for main ideas and supporting details, organization. -and map-reading. Questions are designed to evaluate the students's mastery of these skills and of content subject matter. Some questions are designed to cover collateral chapters in the two books. (RT) a4114111 The Local Connnunky: Long Island and New York City U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IL POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

NYC Travel Sheet V1 2.18

NYC Travel Sheet VER. 1 – 2.10.20 THE THEATER CENTER - THE JERRY ORBACH THEATER Address: 210 West 50th Street, New York NY 10019 (Off of Broadway) The Jerry Orbach Theater is located on the Third Floor, accessible by stair or elevator DIRECTIONS : - Driving directions from Purchase College are page 2 - From Grand Central Station o Take Shuttle to Times Square, Walk towards 50th Street. Take a left onto 50th street, the Theater will be on your left. OR o Walk West from Grand Central to Broadway. Walk North West on Broadway until 50th street. Take a left onto 50th street, the Theater will be on your left. PARKING : FOOD & DINING : - Quik Park (4 min away) - Dig Inn o 888 Broadway, New York, o 856 8th Ave, New York, NY NY - Dunkin’ Donuts o (212) 445-0011 o 850 8th Ave, New York, NY - Icon Parking (3 min away) - Buffalo Wild Wings o 24 hours o 253 W 47th St, New York, o 790 8th Ave, New York, NY NY o (212) 581-8590 - Chipotle o 854 8th Ave FRNT 1, New CONVENIENCE STORES : York, NY - Rite Aid (3 min away) - Starbucks o 24 hours o 750 7th Ave, New York, NY o 301 W 50th St, New York, - McDonalds NY o 1651 Broadway, New - Duane Reade (1 min away) York, NY o 8 am – 8 pm o 1627 Broadway, New York, NY Tuesday there will be catering services in between shows. There will be a vegetarian option but if you are a picky eater or have other dietary restrictions please plan ahead. -

All Hazards Plan for Baltimore City

All-Hazards Plan for Baltimore City: A Master Plan to Mitigate Natural Hazards Prepared for the City of Baltimore by the City of Baltimore Department of Planning Adopted by the Baltimore City Planning Commission April 20, 2006 v.3 Otis Rolley, III Mayor Martin Director O’Malley Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction .........................................................................................................1 Plan Contents....................................................................................................................1 About the City of Baltimore ...............................................................................................3 Chapter Two: Natural Hazards in Baltimore City .....................................................................5 Flood Hazard Profile .........................................................................................................7 Hurricane Hazard Profile.................................................................................................11 Severe Thunderstorm Hazard Profile..............................................................................14 Winter Storm Hazard Profile ...........................................................................................17 Extreme Heat Hazard Profile ..........................................................................................19 Drought Hazard Profile....................................................................................................20 Earthquake and Land Movement -

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY and PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY AND PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative OVERVIEW In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative developed an Emergency Food Strategy. An Emergency Food Planning team, comprised of City agencies and critical nonprofit partners, convened to guide the City’s food insecurity response. The strategy includes distributing meals, distributing food, increasing federal nutrition benefits, supporting community partners, and building local food system resilience. Since COVID-19 reached Baltimore, public-private partnerships have been mobilized; State funding has been leveraged; over 3.5 million meals have been provided to Baltimore youth, families, and older adults; and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Online Purchasing Pilot has launched. This document provides a summary of distribution of food boxes (grocery and produce boxes) from April to June, 2020, and reviews the next steps of the food distribution response. GOAL STATEMENT In response to COVID-19 and its impact on health, economic, and environmental disparities, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative has grounded its short- and long-term strategies in the following goals: • Minimizing food insecurity due to job loss, decreased food access, and transportation gaps during the pandemic. • Creating a flexible grocery distribution system that can adapt to fluctuating numbers of cases, rates of infection, and specific demographics impacted by COVID-19 cases. • Building an equitable and resilient infrastructure to address the long-term consequences of the pandemic and its impact on food security and food justice. RISING FOOD INSECURITY DUE TO COVID-19 • FOOD INSECURITY: It is estimated that one in four city residents are experiencing food insecurity as a consequence of COVID-191. -

Download This

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) r~ _ B-1382 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Completelhe National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property I historic name Highfield House____________________________________________ other names B-1382___________________________________________________ 2. Location street & number 4000 North Charles Street ____________________ LJ not for publication city or town Baltimore___________________________________________________ D vicinity state Maryland code MD county Baltimore City code 510 zip code 21218 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^ nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property E] meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally D statewide ^ locally. -

Kimmel in the C M Nity

THE SIDNEY KIMMEL COMPREHENSIVE CANCER CENTE R AT JOHNS HOPKINS KIMMEL IN THE C MNITY PILLARS OF PROGRESS Closing the Gap in Cancer Disparities MUCH PROGRESS HAS been made in Maryland toward eliminating cancer disparities, and I am very proud of the role the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center has played in this progress. Overcoming cultural and institutional barriers and increasing minority participation in clinical trials is a priority at the Kimmel Cancer Center. Programs like our Center to Reduce Cancer Disparities, Office of Community Cancer Research, the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund at Johns Hopkins, and Day at the Market are helping us obtain this goal. Historical Trends (1975-2012) The challenge before Maryland is greater than Mortality, Maryland most states. Thirty percent of Maryland’s citizens are All Cancer Sites, Both Sexes, All Ages Deaths per 100,000 resident population African-American, compared to a national average 350 of 13 percent. We view our state’s demographics as 300 black (includes hispanics) an opportunity to advance the understanding of 250 factors that cause disparities, unravel the science White (includes hispanics) 200 that may also play a contributory role, and become the model for the rest of the country. Our experts are 150 setting the standards for removing barriers and 100 hispanic (any race) improving cancer care for African-Americans and 50 other minorities in Maryland and around the world. 0 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Although disparities still exist in Maryland, we year of Death continue to close that gap. Overall cancer death rates have declined in our state, and we have narrowed the gap in cancer death disparities between African -American and white Marylanders by more than 60 percent since 2001, far exceeding national progress. -

Inner Harbor West

URBAN RENEWAL PLAN INNER HARBOR WEST DISCLAIMER: The following document has been prepared in an electronic format which permits direct printing of the document on 8.5 by 11 inch dimension paper. If the reader intends to rely upon provisions of this Urban Renewal Plan for any lawful purpose, please refer to the ordinances, amending ordinances and minor amendments relevant to this Urban Renewal Plan. While reasonable effort will be made by the City of Baltimore Development Corporation to maintain current status of this document, the reader is advised to be aware that there may be an interval of time between the adoption of any amendment to this document, including amendment(s) to any of the exhibits or appendix contained in the document, and the incorporation of such amendment(s) in the document. By printing or otherwise copying this document, the reader hereby agrees to recognize this disclaimer. INNER HARBOR WEST URBAN RENEWAL PLAN DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT BALTIMORE, MARYLAND ORIGINALLY APPROVED BY THE MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL OF BALTIMORE BY ORDINANCE NO. 1007 MARCH 15, 1971 AMENDMENTS ADDED ON THIS PAGE FOR CLARITY NOVEMBER, 2004 I. Amendment No. 1 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance 289, dated April 2, 1973. II. Amendment No. 2 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance No. 356, dated June 27, 1977. III. (Minor) Amendment No. 3 approved by the Board of Estimates on June 7, 1978. IV. Amendment No. 4 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance No. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

B-4480 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word process, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name One Charles Center other names B-4480 2. Location street & number 100 North Charles Street Q not for publication city or town Baltimore • vicinity state Maryland code MP County Independent city code 510 zip code 21201 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this G3 nomination • request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property C3 meets • does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally • statewide K locally. -

ADDENDUM a Case 1:03-Cv-01058-JFM Document 269-2270-1 Filed 08/15/1308/19/13 Page 2 of 30

Case 1:03-cv-01058-JFM Document 269-2270-1 Filed 08/15/1308/19/13 Page 1 of 30 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARYLAND BETSY CUNNINGHAM et al. : Plaintiffs : Civil Action No. JFM-03-1058 vs. : KIMBERLY AMPREY FLOWERS et al. : Defendants : CONSENT DECREE ADDENDUM A Case 1:03-cv-01058-JFM Document 269-2270-1 Filed 08/15/1308/19/13 Page 2 of 30 RULES AND REGULATIONS of the CITY OF BALTIMORE. DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION AND PARKS Affecting Management, Use, Government And Preservation With Respect To All Land, Property and Activities Under The Control Of THE DIRECTOR OF THE DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION AND PARKS Whereas Article VII, Section 67(f) of the Baltimore City Charter, 1996 Edition, as amended, provides as follows: “The Director of Recreation and Parks shall have the following powers and duties: (f) To adopt and enforce rules and regulations for the management, use, government and preservation of order with respect to all land, property, and activities under the control of the Department. To carry out such regulations, fines may be imposed for breaches of the Rules and Regulations as provided by law." Now, therefore, the Director of the Department of Recreation and Parks on this ______day of _________________, 2013, does make, publish and declare the following Rules and Regulations for the government and preservation of order within all areas over which the regulatory powers of the Director extend. The new rules and regulations shall be effective as of this date. All former rules and regulations previously issued, declared or printed are hereby amended and superseded. -

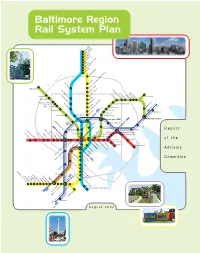

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

The Journal of the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc

The Journal of the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc. The the ageissue 2016 NOV/DEC $7 USD €10 EUR www.dramatistsguild.com FrontCOVER.indd 1 10/5/16 12:57 PM To enroll, go to http://www.dginstitute.org SEP/OCTJul/Aug DGI 16 ad.indd FrontCOVERs.indd 1 2 5/23/168/8/16 1:341:52 PM VOL. 19 No 2 TABLE OF NOV/DEC 2016 2 Editor’s Notes CONTENTS 3 Dear Dramatist 4 News 7 Inspiration – KIRSTEN CHILDS 8 The Craft – KAREN HARTMAN 10 Edward Albee 1928-2016 13 “Emerging” After 50 with NANCY GALL-CLAYTON, JOSH GERSHICK, BRUCE OLAV SOLHEIM, and TSEHAYE GERALYN HEBERT, moderated by AMY CRIDER. Sidebars by ANTHONY E. GALLO, PATRICIA WILMOT CHRISTGAU, and SHELDON FRIEDMAN 20 Kander and Pierce by MARC ACITO 28 Profile: Gary Garrison with CHISA HUTCHINSON, CHRISTINE TOY JOHNSON, and LARRY DEAN HARRIS 34 Writing for Young(er) Audiences with MICHAEL BOBBITT, LYDIA DIAMOND, ZINA GOLDRICH, and SARAH HAMMOND, moderated by ADAM GWON 40 A Primer on Literary Executors – Part One by ELLEN F. BROWN 44 James Houghton: A Tribute with JOHN GUARE, ADRIENNE KENNEDY, WILL ENO, NAOMI WALLACE, DAVID HENRY HWANG, The REGINA TAYLOR, and TONY KUSHNER Dramatistis the official journal of Dramatists Guild of America, the professional organization of 48 DG Fellows: RACHEL GRIFFIN, SYLVIA KHOURY playwrights, composers, lyricists and librettists. 54 National Reports It is the only 67 From the Desk of Dramatists Guild Fund by CHISA HUTCHINSON national magazine 68 From the Desk of Business Affairs by AMY VONVETT devoted to the business and craft 70 Dramatists Diary of writing for 75 New Members theatre. -

Exhibit a Case 1:20-Cv-08899-CM Document 74-1 Filed 05/05/21 Page 2 of 20

Case 1:20-cv-08899-CM Document 74-1 Filed 05/05/21 Page 1 of 20 Exhibit A Case 1:20-cv-08899-CM Document 74-1 Filed 05/05/21 Page 2 of 20 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK THE CLEMENTINE COMPANY, LLC No. 1:20-cv-08899-CM d/b/a THE THEATER CENTER; PLAYERS THEATRE MANAGEMENT FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT CORP. d/b/a THE PLAYERS THEATRE; WEST END ARTISTS COMPANY d/b/a THE ACTORS TEMPLE THEATRE; SOHO PLAYHOUSE INC. d/b/a SOHO PLAYHOUSE; CARAL LTD. d/b/a BROADWAY COMEDY CLUB; and DO YOU LIKE COMEDY? LLC d/b/a NEW YORK COMEDY CLUB Plaintiffs, -against- ANDREW M. CUOMO, in his official capacity as Governor of the State of New York; BILL DE BLASIO, in his official capacity as Mayor of New York City, Defendants. 1. Plaintiffs The Clementine Company, LLC d/b/a The Theater Center; Players Theatre Management Corp. d/b/a The Players Theatre; West End Artists Company d/b/a The Actors Temple Theatre; SoHo Playhouse Inc. d/b/a SoHo Playhouse; Caral Ltd. d/b/a Broadway Comedy Club; and Do You Like Comedy? LLC d/b/a New York Comedy Club for their Complaint against Defendants Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio, allege as follows: 1 Case 1:20-cv-08899-CM Document 74-1 Filed 05/05/21 Page 3 of 20 INTRODUCTION 2. This civil rights lawsuit seeks to vindicate the constitutional rights of free speech and equal protection for the Plaintiff theaters and comedy clubs, which have been subject to unequal closure orders for more than a year.