Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

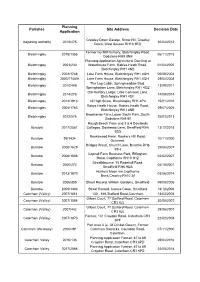

Parishes Planning Application Site Address Decision Date

Planning Parishes Site Address Decision Date Application Crawley Down Garage, Snow Hill, Crawley Adjoining Authority 2012/475 30/04/2012 Down, West Sussex RH10 3EQ Former Ivy Mill Nursery, Bletchingley Road, Bletchingley 2015/1358 06/11/2015 Godstone RH9 8NB Planning Application Agricultural Dwelling at Bletchingley 2003/230 Waterhouse Farm, Rabies Heath Road, 01/04/2005 Bletchingley RH1 4NB Bletchingley 2003/1748 Lake Farm House, Bletchingley RH1 4QH 05/08/2004 Bletchingley 2003/1748/A Lake Farm House, Bletchingley RH1 4QH 29/04/2008 The Log Cabin, Springmeadow Stud, Bletchingley 2010/459 13/09/2011 Springbottom Lane, Bletchingley RH1 4QZ Old Rectory Lodge, Little Common Lane, Bletchingley 2014/278 14/08/2014 Bletchingley RH1 4QF Bletchingley 2014/1913 46 High Street, Bletchingley RH1 4PA 15/01/2016 Rabys Heath House, Rabies Heath Road, Bletchingley 2004/1763 29/07/2005 Bletchingley RH1 4NB Brooklands Farm,Lower South Park,,South Bletchingley 2012/576 25/03/2013 Godstone,Rh9 8lf Rough Beech Farm and 3 & 4 Dowlands Burstow 2017/2581 Cottages, Dowlands Lane, Smallfield RH6 13/12/2018 9SD Rookswood Farm, Rookery Hill Road, Burstow 99/1434 10/11/2000 Outwood. Bridges Wood, Church Lane, Burstow RH6 Burstow 2006/1629 25/06/2007 9TH Cophall Farm Business Park, Effingham Burstow 2006/1808 02/02/2007 Road, Copthorne RH10 3HZ Streathbourne, 75 Redehall Road, Burstow 2000/272 04/10/2001 Smallfield RH6 9QA Hunters Moon Inn,Copthorne Burstow 2013/1870 03/06/2014 Bank,Crawley,Rh10 3jf Burstow 2006/805 Street Record, William Gardens, Smallfield 09/08/2006 Burstow 2005/1446 Street Record, Careys Close, Smallfield 18/12/2006 Caterham (Valley) 2007/1814 130 - 166,Stafford Road,Caterham 13/03/2008 Gilbert Court, 77 Stafford Road, Caterham Caterham (Valley) 2007/1088 30/08/2007 CR3 6JJ Gilbert Court, 77 Stafford Road, Caterham Caterham (Valley) 2007/442 28/06/2007 CR3 6JJ Former, 131 Croydon Road, Caterham CR3 Caterham (Valley) 2007/1870 22/02/2008 6PF Part Area 3 (e. -

January 2021 Minutes

Chelsham & Farleigh Parish Council The minutes of the virtual meeting over Zoom of the Parish Council of Chelsham & Farleigh held on Monday 4th January 2021 at 7:30pm Attendees: Cllr Jan Moore - Chairman Cllr Peter Cairns Cllr Lesley Brown Cllr Barbara Lincoln Cllr Neil Chambers Cllr Jeremy Pursehouse ( Parish & District Councillor) Cllr Celia Caulcott (District Councillor) Cllr Becky Rush (County Councillor) Mrs Maureen Gibbins - Parish Clerk & RFO ————————————————————————————————— M I N U T E S 1. Apologies for absence Cllr Nancy Marsh and District Cllr Simon Morrow 2. Declaration of Disclosable Pecuniary Interest by Councillors of personal pecuniary interests in matters on the agenda, the nature of any interests, and whether the member regards the interest to be prejudicial under the terms of the new Code of Conduct. Anyone with prejudicial interest must, unless an exception applies, or a dispensation has been issued, withdraw from the meeting. There was no specific declaration of interest although all the Councillors have an interest in the area due to living in the Parish 3. A period of fifteen minutes (including County and District Councillors reports) are available for the public to express a view or ask a question on relevant matters on the following agenda. 10 members of the public were in attendance of which 8 were observing the meeting and 1 spoke regarding the high speed fibre broadband and another the issues regarding the bridleway at Holt Wood. County Cllr Becky Rush - had a site meeting with residents prior to Christmas in relation to the highways issues regarding the crematorium. Cllr Rush is meeting with Highways Officers on 8th January raise the concerns and issues highlighted by resi- dents at the pre Christmas meeting. -

The Harvard Classics Eboxed

0113 DSIS Qil3D THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. English Poetry IN THREE VOLUMES VOLUME II From Collins to Fitzgerald ^ith Introductions and l>iotes Yolume 41 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, igro By p. F. Collier & Son uanufactuked in v. s. a. CONTENTS William Collins page FiDELE 475 Ode Written in mdccxlvi 476 The Passions 476 To Evening 479 George Sewell The Dying Man in His Garden 481 Alison Rutherford Cockburn The Flowers of the Forest 482 Jane Elliot Lament for Flodden 483 Christopher Smart A Song to David 484 Anonymous Willy Drowned in Yarrow 498 John Logan The Braes of Yarrow 500 Henry Fielding A Hunting Song 501 Charles Dibdin Tom Bowling 502 Samuel Johnson On the Death of Dr. Robert Levet 503 A Satire 504 Oliver Goldsmith When Lovely Woman Stoops 505 Retaliation 505 The Deserted Village 509 The Traveller; or, A Prospect of Society 520 Robert Graham of Gartmore If Doughty Deeds 531 Adam Austin For Lack of Gold 532 465 466 CONTENTS William Cowper page Loss OF THE Royal George 533 To A Young Lady 534 The Poplar Field 534 The Solitude of Alexander Selkirk 535 To Mary Unwin 536 To the Same 537 Boadicea: An Ode 539 The Castaway 54" The Shrubbery 54^ On the Receipt of My Mother's Picture Out of Norfolk 543 The Diverting History of John Gilpin 546 Richard Brinsley Sheridan Drinking Song 554 Anna Laetitia Barbauld Life 555 IsoBEL Pagan (?) Ca' the Yowes to the Knowes 556 Lady Anne Lindsay AuLD Robin Gray 557 Thomas Chatterton Song from ^lla 558 -

Planning Applications: Received and Determined Week Ending – 09.03.2016

Planning Applications: R eceived and D etermined Week ending – 09.03.2016 Viewing Planning Applications All of these applications, including forms, plans and supporting information can be viewed online by following this link. http://planning.reigate-banstead.gov.uk/online-applications/ The new planning applications search will enable viewing, tracking and commenting on planning applications Commenting on Planning Applications Any observations you may have should be sent as soon as possible to the Head of Places and Planning or by following the link to the Council’s new planning application search facility http://planning.reigate-banstead.gov.uk/online-applications/ This will enable viewing, tracking and commenting on planning applications In the interests of economy, comments regarding planning applications will not be acknowledged. Access to Information The Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985, allows members of the public, including the applicant, the right to examine and receive copies of any letters received in relation to an application three days in advance of the matter being considered by the appropriate Committee and the Freedom of Information Act 2000 affords any person a similar right at any time. Furthermore, the Council operates an “open file” procedure allowing public access to planning application files held at the Town Hall and placing copies of representations received on its web site. Data on the website is redacted to avoid releasing personal information. Explanatory Notes - A glossary of the terms used within this publication is set out below. Type of Application Outline: - approval is sought in principle without full details (these would follow in Reserved Matter applications) Reserved Matter: - a detailed application following Outline approval Full planning: - a single, detailed application, including full plans and elevations, as appropriate, instead of Outline and Reserved Matter applications Change of use: - application seeking approval to use land or buildings for a new purpose (e.g. -

The Holt Chelsham Surrey the Holt Chelsham Surrey

THE HOLT CHELSHAM SURREY THE HOLT CHELSHAM SURREY Introducing the highest standard of living in a small gated semi-rural community....……. A select and exciting development of four unique properties, set in an exclusive oasis of tranquility with substantial grounds. Due to be completed Autumn 2016. LARCHES – 2323 sq. ft. ORCHARD HOUSE – 2268 sq. ft. Commanding three double en-suite bedroom property, with three reception rooms and Truly one of a kind, a building project with potential to create a fantastic three to five stupendous kitchen/diner bedroom house with access to fabulous landscaped gardens OAKLANDS – 1588 sq. ft. THE LODGE – 2287 sq. ft. A perfectly proportioned three double en-suite bedroom home, with feature kitchen/diner & A stunning equine property with three/four bedrooms and excellent living space, with the generous living accommodation rare commodity of 20 acres and substantial equine features GROUNDS & ADDITIONAL LAND There are various packages of land surrounding the development that can be secured by negotiation • These details are for guidance purposes only and should not be relied upon as factual and do not form any part of any contract and their accuracy cannot be guaranteed • Please note that no appliances or systems have been tested. Unless advised, no warranty as to condition or suitability is confirmed. Purchasers are advised to obtain verification from their surveyor/solicitor • Internal photos are advisory of what may appear when the development has been completed • EPC’s are a guide only as the properties are still under development www.clarendonsproperty.co.uk 01737 230 821 The Situation The development is superbly located for London yet occupies a serene, rural position with total peace just moments from the traditional shops, pubs, restaurants and amenities of Warlingham. -

Sunny Brae | Margery Lane | Lower Kingswood | Surrey KT20 7BG

Sunny Brae | Margery Lane | Lower Kingswood | Surrey KT20 7BG These particulars, whilst believed to be accurate are set out as a general guide only for guidance and do not constitute any part of an offer or contract. Intending purchasers should not rely on them as statements of representation of fact, but must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise as to their accuracy. No person in Kennedys’ has the authority to make or give any representation or warranty in respect of the property. door which has space for a washing machine. To the front of M25 is easily accessed at Junction 8 (Reigate Hill) and is Sunny Brae | Margery Lane | the hallway, the WC is located with ceramic tiled walls and within approximately half a mile, which in turn gives access flooring. to both Gatwick and Heathrow airports. Lower Kingswood | Surrey Upstairs there are two good sized double bedrooms, both with We would certainly recommend a viewing and would be fitted wardrobes and vanity sinks, a single bedroom with pleased to send further information or arrange a private KT20 7BG fitted wardrobe and a family bathroom with feature corner viewing. For any assistance, please call our sales team on bath and shower. 01737 817718 Overlooking fields on a quiet residential road, Sunny Brae is To the front of the property, through an electric gate there is a a three bedroom detached property with off street parking, spacious garden offering much seclusion from the road, a and a sizeable garden to include four stables. The large block paved driveway which can accommodate up to 7 accommodation benefits from gas central heating, wooden cars, and garage, and gated access to the rear garden. -

Lower Kingswood Residents' Association

Owen, David From: Lower Kingswood RA Sent: 08 April 2018 18:11 To: reviews Subject: Reigate & Banstead (Borough Council) Electoral Review Importance: High Dear Sir/Madam The following comments are made on behalf of the Lower Kingswood Residents’ Association, and take into account a copy of a report prepared by Reigate & Banstead Borough Council (R&BBC) in April 2017 that has only just become available to us. (a) Suggestions about where the ward boundaries should be: 1. Although the A217/Brighton Road runs north/south through the centre of Lower Kingswood and does sometimes pose difficulties in crossing from one “side" of the village to the other, Lower Kingswood has always been regarded by its residents as one entity. [N.B. The A217 was only made into a dual carriageway in the early 1970s which, at the time, prompted a series of protests by residents of Lower Kingswood.] Furthermore current traffic issues along the A217 are shared by the communities to the north. 2. An anomaly was introduced in 2011/12 with the last Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) review for Surrey County Council wards, which resulted in those properties along the north side of Chipstead Lane being “separated” from the remainder of Lower Kingswood. We cannot agree with the R&BBC report that Chipstead Lane forms a “hard boundary with different communities either side at this point”; and feel that ALL properties in Chipstead Lane form part of Lower Kingswood - with properties from Birch Grove northwards forming part of Kingswood itself. 3. The current ward boundary between Kingswood with Burgh Heath and Chipstead,Hooley & Woodmansterne effectively splits the small community located in Monkswell Lane and Mugswell in two - there is merit in clarifying this one way or the other. -

Local Plan Fact Sheet Warlingham East, Chelsham & Farleigh

Warlingham East, Chelsham & Farleigh This fact sheet is an overview of some of the Once Regulation 19 is complete, an updated Draft key information regarding this ward which is Local Plan is submitted for examination by an contained in the Draft Local Plan. independent Planning Inspector who will undertake a ‘public examination’. It is intended to act as a guide to help better direct you to the relevant information in the Draft Local Key documents Plan which contains more detail. To view the Draft Local Plan and the We have created a map for each of the 20 wards Spatial Strategy document, please visit in the district, as well as listing some important www.tandridge.gov.uk/localplan. information for each including: Key information for Warlingham East, Allocated housing sites – This is a site that has Chelsham & Farleigh been allocated for residential development. Infrastructure – Requirements for roads, schools Allocated Housing Sites and health centres etc. Land at Green Hill Lane and Alexandra Avenue, Town Centres, Local Centres and Neighbourhood Warlingham. HSG16 (estimated size 50 units) Centres- These are protected shopping areas. (in the Green Belt) Tourism Asset – These are protected places to Land at Farleigh Road, Warlingham. HSG17 visit. (estimated size 50 units) (in the Green Belt) Strategic Employment Sites and Important Infrastructure* Employment Sites– Provide a mix of employment Flood works at junction of Farleigh Road and uses which will be protected and intensified. Sunnybank. Garden Community in South Godstone Flood works at junction of Harrow Road and Chelsham Road. The Garden Community will be located in South Godstone. -

Classification of Candidates

LONDON ELECTORAL HISTORY – STEPS TOWARDS DEMOCRACY 7.2 CANDIDATES AND THE CLASSIFICATION OF VOTING BEHAVIOUR The key endeavour of much electoral analysis is to determine what kind of voter polled for what kind of candidate. The historian of the pre- reform electorate is fortunate in this respect in being able to know much more about almost every candidate1 than at any time before the contemporary period.2 Nomination of candidates took place at the hustings, immediately prior to the call for a show of hands by the returning officer. Some who may have sought election nonetheless withdrew from the contest, either following a disappointing canvass or following the show of hands. For the purposes of the LED only those who carried on to the next stage of the electoral process, in eighteenth-century parlance those who ‘stood the poll’, are deemed to have been candidates. Of those who stood the poll, some withdrew during the course of polling. Sometimes this would terminate the election, as when John Graham withdrew from the Westminster election of 1802, or when William Mellish withdrew from the Middlesex contest of 1820. In other cases the withdrawal of a candidate allowed others to continue the contest, although there was no mechanism for re-allocating those votes already given to the candidate who threw in the towel. Thus the withdrawal of William Pitt from the London election of 1784, after he had been nominated for a popular but uncertain seat without his consent, did not preclude a continuation of the contest between the remaining candidates. Even the death of John Hankey, the fifth candidate in the London contest of 1807, did not cause the poll to be terminated. -

Unit 4 BRITISH LITERATURE LIFEPAC 4 the NINETEENTH CENTURY (1798–1900) CONTENTS I

Unit 4 BRITISH LITERATURE LIFEPAC 4 THE NINETEENTH CENTURY (1798–1900) CONTENTS I. THE ROMANTIC ERA • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 William Blake • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 5 William Wordsworth • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 9 Samuel Taylor Coleridge • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 14 Sir Walter Scott • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 26 II. THE LATE ROMANTIC ERA • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 40 Jane Austen • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 40 Charles Lamb • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 47 George Gordon–Lord Byron • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 52 Percy Bysshe Shelley • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 58 John Keats • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 63 III. THE VICTORIAN ERA • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 71 INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 71 Thomas Carlyle • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 75 John Henry Cardinal Newman • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 80 Alfred, Lord Tennyson • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 84 Charles John Huffman Dickens • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 90 Robert Browning • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 100 George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 103 Oscar Wilde • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 109 Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) -

Religion, White Supremacy, and the Rise and Fall of Thomas Dixon, Jr

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2013 "History Written with Lightning": Religion, White Supremacy, and the Rise and Fall of Thomas Dixon, Jr David Michael Kidd College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kidd, David Michael, ""History Written with Lightning": Religion, White Supremacy, and the Rise and Fall of Thomas Dixon, Jr" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623616. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-5k6d-9535 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “History Written With Lightning”: Religion, White Supremacy, and the Rise and Fall of Thomas Dixon, Jr. David Michael Kidd Norfolk, Virginia Master of Arts, University of Florida, 1992 Bachelor of Arts, Auburn University, 1990 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies The College of William and Mary May, 2013 © 2013 David M. Kidd All Rights Reserved APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy David Michael Kidd Approved by the Committee, April, 2013 Committee Chair Professor of American Studies and English, Susan V. -

Comics and Videogames

14 Creating Lara Croft The meaning of the comic books for the Tomb Raider franchise Josefa Much Since the creation of Lara Croft in 1996, it seems impossible to imagine the game industry without her. Her pop-cultural impact certainly affected the gaming industry, but the expansion of her character into a whole franchise has also immortalized her through action figures, cosplay, music videos, and appearances in many other media. If you take a closer look at the franchise, you will find a number of different videogames for different gaming platforms as well as three action films, six novels, and many comic books. Shortly after the release of the very firstTomb Raider game in 1996, the comic book pub- lisher Top Cow released a crossover with their own heroine Sara Pezzini aka Witchblade and Lara Croft: Tomb Raider/ Witchblade (Turner 1997, 1998). The Witchblade comic books were one of Top Cow’s most prominent series. As a result, something very interesting happened: Lara Croft was introduced into a new universe beyond her own games, and thus into a new storyworld. She became part of the Top Cow universe as both franchises collided. Two years later, the Tomb Raider received her own stand- alone comic book series. It not only focused on her adventures, but also on her personal thoughts and approach, introducing different characters and friends of hers. Later on, this would be used to create new crossovers with different Top Cow characters (e.g., Dark Crossing [Holland and Turner 2000a, 2000b]; Endgame [Rieber and Green 2003a, 2003b, 2003c; Silvestri and Tan 2003; Turner 2002c]; the Magdalena crossover [Bonny and Basaldua 2004a, 2004b, 2004c]; the Fathom/ Witchblade/ Tomb Raider crossover [Turner 2000, 2002a, 2002b]).