EXPANDED CHOREOGRAPHY: Shifting the Agency of Movement in the Artificial Nature Project and 69 Positions Mette, Ingvartsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3Rd EDITION 201 4

3rd EDITION 201 4 SATURDAY 14 JUNE FROM 11 AM SUNDAY 15 JUNE FROM 2:30 PM ADMISSION FREE, SUBJECT TO AVAILABILITY (NO ADVANCE BOOKING NECESSARY ) detailed programme available from June 2 SELECTED 20PROJECTS A shared artistic adventure www.danse-elargie.com I www.theatredelaville-paris.com I www.museedeladanse.org COMMUNICATION THÉÂTRE DE LA VILLE Anne-Marie Bigorne 01 48 87 87 39 [email protected] Jacqueline Magnier 01 48 87 84 61 IN PARTNERSHIP WITH [email protected] Marie-Laure Violette 01 48 87 82 73 WITH THE SUPPORT [email protected] 16, QUAI DE GESVRES 75180 PARIS CEDEX 04 The Théâtre de la Ville is supported by Paris Town Hall. Tél. 01 48 87 54 42 The Musée de la danse is supported by the French Ministry of Culture and Communication - the Direction régionale des Affaires Culturelles, the city of Rennes, the regional Council of Brittany and the General Council of llle-et-Vilaine. YOU THINK THAT THE DOORS OF THE THEATRES ARE TOO NAR - ROW ? THAT NEW, WIDER ONES SHOULD BE INVENTED ? YOU THINK THAT THE PRETEXT OF A COMPETITION CAN ALLOW TO CREATE A TRUE, BIG AND FREE HAPPENING ? AN OPPORTUNITY TO CHANGE WHAT IS USUALLY ALLOWED ? YOU THINK THAT COMPETITION TAKES PLACE ON A DAILY BASIS ANYWAY ? THAT SELECTION IS RUTHLESS BUT THAT AT LEAST HERE ON THE STAGE THERE IS ROOM FOR DIAGONALS ? YOU WANT TO TAKE PART , WATCH , GIVE IT . A TRY ? YOU ARE WELCOME AND WE’D LOVE TO SEE YOU. Dance is a dirty job but somebody’s got to do it , Scali Delpeyrat Y E N E P U O P E H T A G A © L’Homme transcendé , Yukio -

Roskilde University

Roskilde University The Striking Presence of Absence A Portrait of Mette Ingvartsen Petersen, Franziska Bork; Butte, Maren Published in: Peripeti Publication date: 2017 Citation for published version (APA): Petersen, F. B., & Butte, M. (2017). The Striking Presence of Absence: A Portrait of Mette Ingvartsen. Peripeti, 26, 73-85. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Portrættet The Striking Presence of Absence 50/50 | Mette Ingvarsen 2004 Foto: Peter Lanaerts The Striking Presence of Absence A Portrait of Mette Ingvartsen Franziska Bork Petersen and Maren Butte A Relational Portrait When does something stop being dance? How far can you take choreography before it becomes an installation or a performance piece? What is choreography in the expanded field – between the arts and between (bodily) movement and discourse? How can one shift the agency of movement? Mette Ingvartsen explores the ontological status of dance and the political implications this entails. -

Magazin Im August 201410 MB

MAGAZIN IM AUGUST Tanz im August | 26.Internationales Festival 15.–30.8.2014 | Berlin Komplettes Programm im Innenteil Miss RevolutionaryTrash anddiszipliniert Spirit das Chaos Dance, Photograph Wolfgang Tillmans trifft Michael Clark Jefta vanFrom Dinther Clubsüber seine toArbeit the mit StageCullbergy and Ballet Risks präsentiert von Liebe Leserin, Dear Reader, lieber Leser You have your hands on “Magazin im August”, a spin-off of Tanz im August Als im Jahr 1988 West-Berlin die International Dance Festival. Born out “Kulturhauptstadt Europas” wurde, hat- of curiosity and of love for both dance te die Stadt, in der wir leben, noch ein and writing, it offers interviews and völlig anderes Gesicht. Mit ihrem unt- features to introduce the exciting ar- rüglichen Gespür für den richtigen tists coming to Berlin in August. In Moment rief Nele Hertling ein Jahr fact, the magazine is inspired by art- später, 1989, Tanz im August ins Le- ists and their thoughts – from all over ben. Unter ihrer Leitung war das Hebbel-Theater gerade als inter- the world. That is why we decided to print the texts and interviews nationales Haus für Koproduktionen und Gastspiele neu eröffnet in German and English. The respective other versions you will find worden. Mit dem Festival schuf sie eine Veranstaltungsplattform, on our website tanzimaugust.de. die seitdem jährlich die maßgeblichen Entwicklungen im zeitge- nössischen Tanz auch an der Spree sichtbar macht. We visited the Brazilian choreographer Marcelo Evelin and talked with his crew in Poland, only minutes before they were going on Kaum mehr als ein Vierteljahrhundert später ist das wiederver- stage – naked and painted all in black. -

STÉPHANE BARBIER BOUVET Lives in Geneva (Ch) and Brussels (Be)

STÉPHANE BARBIER BOUVET lives in Geneva (ch) and Brussels (be) DESIGN COMMISSIONS 2017 Display of Stream the Nowy Teatr, Warsaw, in collaboration with choreographer Ula Sickle. Permanent installation for the exhibition center La Loge, Brussels. 2016 Display of Exhibition space and film set Labor Zer Labor (l-0-l.org), La Friche de la Belle de Mai, Marseille. Art Direction for interior design of the artist residencies of Luma Fondation, Arles. Design of offices and furniture for BETC-Euro RSCG advertising agency, Pantin. 2015 Design of the Bookshop La Librairie (Oraibi and Beck Books), Geneva, with Elise van Mourik. Design of the kitchen system Stack, Bordeaux. nominated for Swiss Design Awards. 2014 Design of the shelving System Olivia. Design of a pier on the Dordogne River in Asques, France (non realised). 2013 Exhibition furniture for Seigneur, accorde à l’esprit un crédit à la production at Circuit, Lausanne. (Kaiser Kraft). Circulation (handrails) enters the Parking Club catalogue, Amsterdam. Design of different furnitures for the Casa Tabarelli by Carlo Scarpa, Bolzano. cloth cabinet, table, paravent. Lighting design for the exhibition Hotel Abisso, Centre d’art Contemporain, Geneva. (Kaiser Kraft). Design for the show of Daniel Dewar et Gregory Gicquel at the galerie Graff Mourgue d’algue, Geneva. (Kaiser Kraft). 2012 Artotheque for the biennale de Belleville, Paris. Cur: Patrice Joly. Project cancelled right after the opening. Exhibition design of La Demeure Joyeuse II at the galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich. Cur: Anne Dressen. The CCLA, with Kaiser Kraft, conception of a cultural center for the village of Les Arques, Cur: Daniel Dewar. -

Performing Arts Flanders Content

PERFORMING ARTS FLANDERS CONTENT FOREWORD 5 PART 1 - OVERVIEW Dance in Flanders 2007-2013. 11 An outline of the dance landscape Pieter T’ Jonck Counting steps. Evolutions in ‘Flemish dance’ from an 31 international perspective (1993-2011) Bart Magnus, Delphine Hesters, Joris Janssens, Wessel Carlier PART 2 - INTERVIEWS ‘We are always social bodies’ 51 An interview with Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker Karlien Vanhoonacker ‘My generation wants reconciliation and collectivity’ 61 An interview with Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui Karlien Vanhoonacker PART 3 - PROFILES Who’s who? An overview of the dance landscape 77 Dance companies 80 Artists 113 Training programmes 125 Intermediaries and supporting organisations 128 ABOUT ‘PERFORMING ARTS FLANDERS’ 141 COLOPHON 144 FOREWORD Perspective: Dance offers the interested reader an insight at several levels into the developing dance landscape of Flanders and Brussels. With its outline of the landscape, new research material and above all a great many portraits of performing artists and producers, as well as an overview of intermediaries, this book provides evidence of a dance scene whose dynamism is considered exceptional throughout the world. The dance scene as it currently exists in Flanders and Brussels is all in all a relatively recent phenomenon. In the 1980s, creating dance in Flanders and Brussels was still work for pioneers. Since then things have changed radically for dance-makers. ‘We once planted a tree in a desert, but now that tree stands in a wood’, said the choreographer Wim Vandekeybus some time ago during a debate organised by VTi – Institute for the Performing Arts in Flanders. Previous research publications from VTi, such as Canaries in the coalmine. -

Workshops & Research

WORKSHOPS & RESEARCH 19 JULY - 15 AUGUST 2015 Workshops in Contemporary Dance and Bodywork for all levels from beginners to professional dancers. Seven phases which can be attended independently from each other (each week- workshop: 1 class per day, each intensive-workshop: 2 classes per day) «impressions'15»: 19 July ! Week1: 20 - 24 July Intensive1: 25 + 26 July Week2: 27 July - 31 July ! Intensive2: 01 + 02 August! Week3: 03 - 07 August! Intensive3: 08 + 09 August! Week4: 19 - 14 August ! «expressions'15»: 15 August Index 3 Artists listed by departments 4 - 134 All workshop descriptions listed by artists 135 - 146 All Field Project descriptions listed by artists 146 - 148 Pro Series descriptions listed by artists 2 AMERICAN EUROPEAN CONTEMPORARY Conny Aitzetmueller | Kristina Alleyne | Sadé Alleyne | Amadour Btissame | Laura Arís | Iñaki Azpillaga | Susanne Bentley | Nicole Berndt-Caccivio | Andrea Boll | Bruno Caverna | Marta Coronado | Frey Faust | David Hernandez | Florentina Holzinger | Peter Jasko | German Jauregui | Kira Kirsch | Clint Lutes | Simon Mayer | Rasmus Ölme | Sabine Parzer | Francesco Scavetta | Rakesh Sukesh | Samantha Van Wissen | Angélique Willkie | Hagit Yakira | David Zambrano IMPROVISATION Eleanor Bauer | Susanne Bentley | David Bloom | Alice Chauchat | DD Dorvillier | Defne Erdur | Alix Eynaudi | Jared Gradinger | Miguel Gutierrez | Andrew de Lotbinière Harwood | David Hernandez | Keith Hennessy | Claudia Heu | Jassem Hindi | Inge Kaindlstorfer | Jennifer Lacey | Benoît Lachambre | Charmaine LeBlanc | Pia Lindy -

Pedagogical and Artistic Team 2020-21

Pedagogical and artistic team 2020-21 Programme coordination Annouk Van Moorsel Annouk Van Moorsel (°1962) studied at the Higher Institute for Dance and the Vrije Uni- versiteit Brussel (Licentiaat in clinical psychology). She worked as a dancer, choreogra- pher and dance teacher. Since 2002 she has been the coordinator of the dance teacher training programme at the Royal Conservatoire of Artesis Hogeschool. She was respon- sible for the quality assurance policy of the department. Since 2007 she is also the Head of the teacher training programmes dance, drama and music and since 2019 the Acting Head of dance. She has worked as a psychologist / therapist and is co-author of the book “4 je mee?” - Initiation lessons for 6-year-olds with crossovers to the art disciplines of drama, dance, music and image. Since 2005 she has been involved as a promoter and co-supervisor in various research projects at the Department of the Royal Conservatoire and the University of Antwerp and is chair of CORPoREAL research group (KCA). She is a member of the Organizing Body of AP Hogeschool, the Council of the School of Arts Royal Conservatoire and the Research Council of the Royal Conservatoire and the Royal Academy of Antwerp. She is a member of CoDA an inter- national research network "Cultures of Dance" that was founded in 2019 on the initiative of Professor Timmy De Laet of the University of Antwerp. Function: Head of Dance and Educational Graduate, Bachelor and Master Programmes Dance, Music, Drama Nienke Reehorst Nienke (°1964) graduated at the Rotterdamse Dansacademie (Codarts) before continu- ing her dance studies in New York. -

Faustin Linyekula

MORE MORE MORE ... FUTURE We deserve more than the vanishing shadows of delusions We deserve more than headlines and media compassion More than the false happiness that blinds our minds More than assistance, we deserve justice More than money, we deserve dignity More than a glorious past, we long for a future MORE MORE MORE...FUTURE Choreographer and director Faustin Linyekula creates intricate and powerful dance/theater/performance works which refl ect on the political, social and cultural history and present day struggles of his home country. Through personal stories, communal activity and beautifully crafted choreography, his works subvert the dominant images of contemporary Congo with their resourcefulness and hope. With more more more...future he takes inspiration from the driving force of ndombolo; bastard daughter of rumba, traditional rhythms, church fanfares and Sex Machine funk, this Congolese pop delivers unstoppable energy. Ndombolo musicians praise their own power, beautiful women, designer clothes and luxury cars -- a fantasy life drawn from soap operas and American music videos -- as if everything is granted in a country where in fact you have to start over again every day. In more more more...future ndombolo expresses not the cheap, thin dreams of money and fame, but the diffi culties, dead ends, and mistakes of previous generations. Linyekula’s choreography embraces creative destruction and stakes a claim to his own no-future society, saying “If it’s impossible for us to send to hell a future that we never had, if it’s diffi cult to go on ruining our pile of ruins, let’s try to dream, the feet firmly kept on the ground, and just imagine more future.” In this raucous and provocative performance three dancers, including Linyekula, twist and rage to the seething poems of Antoine Vumilia Muhindo, a political prisoner in Kinshasa and childhood friend of Linyekula’s, set in song by music director Flamme Kapaya, an exceptional guitarist and a major star in the Congo. -

The Artificial Nature Project and 69 Positions

EXPANDED CHOREOGRAPHY: Shifting the agency of movement in The Artificial Nature Project and 69 positions Mette, Ingvartsen 2016 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Mette, I. (2016). EXPANDED CHOREOGRAPHY: Shifting the agency of movement in The Artificial Nature Project and 69 positions. https://vimeo.com/164552586 Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 The Artificial Nature Series Mette Ingvartsen The Artificial Nature Series This book is part of Mette Ingvartsen’s dissertation Expanded Choreography: Shifting the agency of movement in The Artificial Nature Series and 69 positions. The dissertation has been carried out and supervised within the graduate program in choreography at Stockholm University of the Arts and DOCH School of Dance and Circus. -

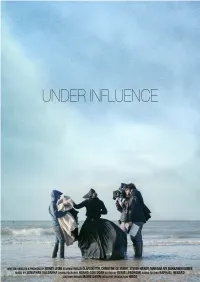

Sidneyleoni-UI-17.Pdf

sidney leoni under influence UNDER INFLUENCE is a fiction feature film portraying the mysterious and psychotic journey of the actress Julia Gordon, who frenetically turns her imagination into a living world away from the humdrum existence of her contemporaries. Frustrated by the character that she is playing in a new motion picture titled Being Kate Winslet, Julia Gordon finds comfort under the influence of charismatic classic film characters – which she repetitively turns into. UNDER INFLUENCE is shaped like a maze of real and naturalistic events, of series of cuts, of shifts and collisions between the real world and fictional ones, of complete imaginary and fantastic situations, of visualization of thoughts, of mental associations, of wishes and fantasies that swirl through the mind of an actress who conveys her dreams to us. The plot being the point of entry into a kaleidoscopic experience of identity and of cinema in the way of a visual, auditory and physical journey. SCREENINGS 01 > 03.10.2015 Dansens Hus, Stockholm (SE) - Screening test - 17.03.2016 Inkonst, Malmö (SE) 25 > 26.03.2016 Beursschouwburg, Brussels (BE) - Belgian Première - 28.04.2016 Centre Culturel Jacques Franck, Brussels (BE) 24.08.2016 Reykjavik Dance Festival, Reykjavik (IS) 26 > 27.08.2016 Tanz im August (HAU Hebbel am Ufer), Berlin (DE) 06.10.2016 Buda Arts Center, Kortrijk (BE) © Thomas Cartron CREDITS Written, directed & produced by: Sidney Leoni Starring: Halla Ólafsdóttir, Christine de Smedt, Steven Wendt, Mariana My Suikkanen Gomes, Alexandra Cismondi, Elias -

Cyberarts 2019

CyberArts 2019 Prix Ars ElectronicaPrix Ars Electronica · STARTS · STARTS Prize'19 Prize’17 ars.electronica.art/prixprixars.aec.at CyberArts 2019 CyberArts Prix ArsElectronica Prix ARS ELECTRONICA ARS Art, Technology &Society Art, Technology S+T+ARTS Prize'19 CyberArts 2019 Prix Ars Electronica S+T+ARTS Prize'19 ARS ELECTRONICA Art, Technology & Society Hannes Leopoldseder · Christine Schöpf · Gerfried Stocker CyberArts 2019 Prix Ars Electronica 2019 Computer Animation · Artificial Intelligence & Life Art Digital Musics & Sound Art · u19–create your world STARTS Prize'19 Grand Prize of the European Commission honoring Innovation in Technology, Industry and Society stimulated by the Arts Contents Prix Ars Electronica 2019 10 Christine Schöpf, Gerfried Stocker – Prix Ars Electronica 2019 12 Hannes Leopoldseder – Turning Point: At the Dawn of a New World COMPUTER ANIMATION 20 Extending Screens: Extending Vision – Statement of the Computer Animation Jury 24 Kalina Bertin, Sandra Rodriguez, Nicolas S. Roy, Fred Casia – ManicVR · Golden Nica 28 Ruini Shi – Strings 30 Cindy Coutant – Undershoot, sensitive data: Cristiano 32 Studio Job, Joris & Marieke – A Double Life 34 Tomek Popakul – ACID RAIN 36 Siyeon Kim / ARTLab – City Rhythm 38 Martina Scarpelli – Egg 40 Universal Everything – Emergence 42 Sam Gainsborough – Facing It 44 Lilli Carré, David Sprecher – Huskies 46 Michael Frei, Mario von Rickenbach / Playables – KIDS 48 Theo Triantafyllidis – Nike 50 Réka Bucsi – Solar Walk 52 Ismaël Joffroy Chandoutis / Fresnoy – Swatted 54 Romain Tardy -

Radialsystem 6 PM–11 PM Shareholders Is a Three-Part Project Curated by the Interdisciplinary Series WITH: Montag Modus About Practices and Politics of Sharing

14 AUG radialsystem 6 PM–11 PM ShareHolders is a three-part project curated by the interdisciplinary series WITH: Montag Modus about practices and politics of sharing. Montag Modus is a Berlin-based series that involves both local as well as artists and cultural workers from Central and Eastern Europe. Its program is centered around performance art, choreography and time-based media. Within one evening Pankaj Tiwari Sunny Pfalzer it features multiple works that are often presented alongside one another & Maria Magdalena Kozłowska & Marshall Vincent in an exhibition-like situation. The kick-off event of ShareHolders takes experiences of societal and environmental changes at its starting point to explore the necessary conditions for coming together, for tending to environments and to each other in a post pandemic world. Through a range of performative strategies, somatic techniques and queer re-imaginings it investigates what it means Maru Mushtrieva Justin F. Kennedy, to share space; the responsibilities to hold and the strategies to claim & Liudmila Savelyeva Emma Waltraud Howes, space. The performance-exhibition hosts different practices of sharing Ethan Braun, by proposing and realizing multiple forms of access and participation. Caterina Veronesi & Marcel Darienzo The booklet gives an insight into the background of the presented works. A neutral, descriptive tone was deliberately avoided in order to preserve and reflect the personal voices of the respective artists. SERAFINE1369 Omsk Social Club & Hollow HALLE: ground floor SAAL: ground floor DECK: 3rd floor max 130 people max 25 people max 30 people *An ongoing performance with open door policy. Pankaj Tiwari TENT: During Montag Modus TENT hosts the performance Constructive Inter- ference by Pankaj Tiwari and Maria Magdalena Kozłowska.