Some Illustrated Jain Manuscripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julia A. B. Hegewald

Table of Contents 3 JULIA A. B. HEGEWALD JAINA PAINTING AND MANUSCRIPT CULTURE: IN MEMORY OF PAOLO PIANAROSA BERLIN EBVERLAG Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 3 13.04.2015 13:45:43 2 Table of Contents STUDIES IN ASIAN ART AND CULTURE | SAAC VOLUME 3 SERIES EDITOR JULIA A. B. HEGEWALD Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 2 13.04.2015 13:45:42 4 Table of Contents Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographical data is available on the internet at [http://dnb.ddb.de]. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. Coverdesign: Ulf Hegewald. Wall painting from the Jaina Maṭha in Shravanabelgola, Karnataka (Photo: Julia A. B. Hegewald). Overall layout: Rainer Kuhl Copyright ©: EB-Verlag Dr. Brandt Berlin 2015 ISBN: 978-3-86893-174-7 Internet: www.ebverlag.de E-Mail: [email protected] Printed and Hubert & Co., Göttingen bound by: Printed in Germany Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 4 13.04.2015 13:45:43 Table of Contents 7 Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 1 Introduction: Jaina Manuscript Culture and the Pianarosa Library in Bonn Julia A. B. Hegewald ............................................................................ 13 Chapter 2 Studying Jainism: Life and Library of Paolo Pianarosa, Turin Tiziana Ripepi ....................................................................................... 33 Chapter 3 The Multiple Meanings of Manuscripts in Jaina Art and Sacred Space Julia A. -

Voliirw(People and Places).Pdf

Contents of Volume II People and Places Preface to Volume II ____________________________ 2 II-1. Perception for Shared Knowledge ___________ 3 II-2. People and Places ________________________ 6 II-3. Live, Let Live, and Thrive _________________ 18 II-4. Millennium of Mahaveer and Buddha ________ 22 II-5. Socio-political Context ___________________ 34 II-6. Clash of World-Views ____________________ 41 II-7. On the Ashes of the Magadh Empire _________ 44 II-8. Tradition of Austere Monks ________________ 50 II-9. Who Was Bhadrabahu I? _________________ 59 II-10. Prakrit: The Languages of People __________ 81 II-11. Itthi: Sensory and Psychological Perception ___ 90 II-12. What Is Behind the Numbers? ____________ 101 II-13. Rational Consistency ___________________ 112 II-14. Looking through the Parts _______________ 117 II-15. Active Interaction _____________________ 120 II-16. Anugam to Agam ______________________ 124 II-17. Preservation of Legacy _________________ 128 II-18. Legacy of Dharsen ____________________ 130 II-19. The Moodbidri Pandulipis _______________ 137 II-20. Content of Moodbidri Pandulipis __________ 144 II-21. Kakka Takes the Challenge ______________ 149 II-22. About Kakka _________________________ 155 II-23. Move for Shatkhandagam _______________ 163 II-24. Basis of the Discord in the Teamwork ______ 173 II-25. Significance of the Dhavla _______________ 184 II-26. Jeev Samas Gatha _____________________ 187 II-27. Uses of the Words from the Past ___________ 194 II-28. Biographical Sketches __________________ 218 II - 1 Preface to Volume II It's a poor memory that only works backwards. - Alice in Wonderland (White Queen). Significance of the past emerges if it gives meaning and context to uncertain world. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

Lord Mahavira Publisher's Note

LORD MAHAVIRA [A study in Historical Perspective] BY BOOL CHAND, M.A. Ph.D (Lond.) P. V. Research Institute Series: 39 Editor: Dr. Sagarmal Jain With an introduction by Prof. Sagarmal Jain P.V. RESEARCH INSTITUTE Varanasi-5 Published by P.V. Research Institute I.T.I. Road Varanasi-5 Phone:66762 2nd Edition 1987 Price Rs.40-00 Printed by Vivek Printers Post Box No.4, B.H.U. Varanasi-5 PUBLISHER’S NOTE 1 Create PDF with PDF4U. If you wish to remove this line, please click here to purchase the full version The book ‘Lord Mahavira’, by Dr. Bool Chand was first published in 1948 by Jaina Cultural Research Society which has been merged into P.V. Research Institute. The book was not only an authentic piece of work done in a historical perspective but also a popular one, hence it became unavailable for sale soon. Since long it was so much in demand that we decided in favor of brining its second Edition. Except some minor changes here and there, the book remains the same. Yet a precise but valuable introduction, depicting the relevance of the teachings of Lord Mahavira in modern world has been added by Dr. Sagarmal Jain, the Director, P.V. Research Institute. As Dr. Jain has pointed out therein, the basic problems of present society i.e. mental tensions, violence and the conflicts of ideologies and faith, can be solved through three basic tenets of non-attachment, non-violence and non-absolutism propounded by Lord Mahavira and peace and harmony can certainly be established in the world. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

JAIN VALUES, WORSHIP AND THE TIRTHANKARA IMAGE B.A., University of Washington, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard / THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1980 (c)Roy L. Leavitt In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date 14 October 1980 The main purpose of the thesis is to examine Jain worship and the role of the Jains1 Tirthankara images in worship. The thesis argues that the worshipper emulates the Tirthankara image which embodies Jain values and that these values define and, in part, dictate proper behavior. In becoming like the image, the worshipper's actions ex• press the common concerns of the Jains and follow a pattern that is prized because it is believed to be especially Jain. The basic orientation or line of thought is that culture is a system of symbols. These symbols are implicit agreements among the community's members, agreements which entail values and which permit the Jains to meaningfully interpret their experiences and guide their actions. -

Sculptural Art of Jains in Odisha: a Study

International Journal of Humanities And Social Sciences (IJHSS) ISSN (P): 2319-393X; ISSN (E): 2319-3948 Vol. 6, Issue 4, Jun - Jul 2017; 115 - 126 © IASET SCULPTURAL ART OF JAINS IN ODISHA: A STUDY AKHAYA KUMAR MISHRA Lecturer in History, Balugaon College, Balugaon, Khordha, Odisha, India ABSTRACT In ancient times, Odisha was known as Utkal, which means utkarsh in kala i.e., excellent in the arts. Its rich artistic legacy permeates through time, into modern decor, never deviating from the basics. Each motif or intricate pattern, draws its inspiration from a myth or folklore, or from the general ethos itself. Covered by the dense forests, soaring mountains, sparkling waterfalls, murmuring springs, gurgling rivers, secluded dales, deep valleys, captivating beaches and sprawling lake, Odisha is a kaleidoscope of past splendor and present glory. Being the meeting place of Aryan and Dravidian cultures, with is delightful assimilations, from the fascinating lifestyle of the tribes, Odisha retains in its distinct identity, in the form of sculptural art, folk art and performing art. The architectural wonders of Odisha must be seen in the Jain caves, which speak about the fine artistry of Odisha’s craftsmen, in the bygone era. The Odias displayed their remarkable creative power, in the Jain sculptural art. While they built their caves like giants, they sculptured the caves like master artists. The theme of these sculptures was so varied, for the artist and his imagination so deep that, as if, he was writing an epic on the surface of the stone. KEYWORDS: Art, Architecture, Sculpture, Prolific INTRODUCTION Odisha has a rich and unique heritage of art traditions, beginning from the sophisticated ornate temple architecture, and sculpture to folk arts, in different forms. -

Depiction of Yaksha and Yakshi's in Jainism

International Journal of Applied Research 2016; 2(2): 616-618 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 Depiction of Yaksha and Yakshi’s in Jainism IJAR 2016; 2(2): 616-618 www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 13-12-2015 Dr. Venkatesha TS Accepted: 15-01-2016 Jainism, one of the oldest living faiths of India, has a hoary antiquity in Karnataka. No doubt, Dr. Venkatesha TS UGC-POST Doctoral Fellow this religion took its birth in North India. However, within a couple of centuries of its birth, Department of Studies and this religionis said to have entered into Karnataka. Jaina tradition ascribes III C.B.C. as the Research in History and date of entry of this religion to south India, and in particular to Karnataka. After this period Archaeology Tumkur Jainism grew from strength to strength and heralded a glorious era, never to be witnessed in University, Tumkur-572103 any part of India, to become a religion next only to Brahmanism in popularity and number. Though Jainism was spread over different parts of south India within the first few centuries of the Christian era, its nucleus as well as the stronghold was southern Karnataka. In fact, it is the general opinion that the history of Jainism in south India is predominantly the history of that religion in Karnataka. Such was the prominence that this religion enjoyed throughout the first millennium A.D. Liberal royal patronage extended by the Kadambas, the Gangas, the Chalukyas of Badami, the Rashtrakutas, the Nolambas, the Kalyana Chalukyas, the Hoysalas, the Vijayanagar rulers and their successors, resulted in the uninterrupted growth of this religion in southern Karnataka. -

Why Must There Be an Omniscient in Jainism?

5 WHY MUST THERE BE AN OMNISCIENT IN JAINISM? Sin Fujinaga 1. It is a well-known fact that the Jains deny the existence of God as a creator of this universe while the Hindus admit such existence. According to Jainism this universe has no beginning and no end, so no being has created it. On the other hand, the Jains are very eager to establish the existence of an omniscient person. Such a person is denied in the Hindu tradition. The Jain saviors or tirthaÅkaras are sometimes called bhagavan, a Lord. This word does not indicate a creator but rather means a respected person with all-pervading knowledge. Generally speaking, the omniscience of the tirthaÅkaras is such that they grasp each and every thing of the universe not only in the present time, but in the past and the future also. The view on the omniscience of tirthaÅkaras, however, is not ubiquitous in the Jaina tradition. Kundakunda remarks, “From the practical point of view an omniscient Lord perceives and knows all, while from the real point of view he perceives and knows his own soul.”1 Buddhism, another non-Hindu school of Indian philosophy, maintains that the founder Buddha is omniscient. In the Pali canon, the Buddha is sometimes described with the word savvaññu or sabbavid, both of which mean omniscient.2 But he is also said to recognize only the religious truth of dharma, more precisely, the four noble truths, caturaryasatya. This means that the omniscient Buddha does not need to know details of matters such as the number of insects in this world. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

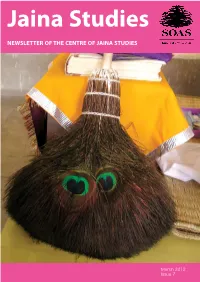

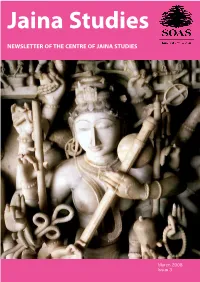

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2012 Issue 7 CoJS Newsletter • March 2012 • Issue 7 Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES Contents: 4 Letter from the Chair Conferences and News 5 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Programme 7 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Abstracts 11 The Paul Thieme Lectureship in Prakrit 12 Jaina Narratives: SOAS Jaina Studies Workshop 2011 15 SOAS Workshop 2013: Jaina Logic 16 Old Voices, New Visions: Jains in the History of Early Modern India at the AAS 18 How Do You ‘Teach’ Jainism? 20 Sanmarga: International Conference on the Influence of Jainism in Art, Culture & Literature 22 Jaina Studies Section at the 15th World Sanskrit Conference 24 Jiv Daya Foundation: Jainism Heritage Preservation Effort 24 Jaina Studies Certificate at SOAS Research 25 Stūpa as Tīrtha: Jaina Monastic Funerary Monuments 28 Peacock-Feather Broom (Mayūra-Picchī): Jaina Tool for Non-Violence 30 A Digambar Icon of 24 Jinas at the Ackland Art Museum 34 Life and Works of the Kharatara Gaccha Monk Jinaprabhasūri (1261-1333) 37 Jains in the Multicultural Mughal Empire 40 Fragile Virtue: Interpreting Women’s Monastic Practice in Early Medieval India Jaina Art 42 The Elegant Image: Bronzes at the New Orleans Museum of Art 45 Notes on Nudity in Digambara Jaina Art 47 Victoria & Albert Museum Jaina Art Fund 48 Continuing the Tradition: Jaina Art History in Berlin Publications 49 Jaina Studies Series 51 International Journal of Jaina Studies 52 International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 52 Digital Resources in Jaina Studies at SOAS Prakrit Studies 53 Prakrit Courses at SOAS Jaina Studies at the University of London 54 Postgraduate Courses in Jainism at SOAS 54 PhD/MPhil in Jainism at SOAS 55 Jaina Studies at the University of London On the Cover The Peacock-Feather Broom (mayūra-picchī) of Āryikā Muktimatī Mātājī, in the Candraprabhu Digambara Jain Baṛā Mandira, in Bārābaṅkī/U.P. -

The Jain History, Art and Architecture in Pakistan: a Fresh Light1

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan Volume No. 56, Issue No. 1 (January - June, 2019) Muhammad Iqbal Chawla * Muhammad Hameed** Syeda Mahnaz Hassan *** The Jain History, Art and Architecture in Pakistan: A Fresh Light1 Abstract This paper attempts to understand the history, art and architecture of Jains in Pakistan with the new perspective. Among ancient religions of Indian Subcontinent, Jainism is the only one that remained a practicing religion in Pakistan till the country gained independence in 1947. Historical records clearly mention presence of jain community in major cities of Pakistan. Archaeological data consisting of jain temples, community halls and other shrines also throws light on the contribution of jains in the socio-religious, cultural, architectural and artistic activities of the country. Researches related to Indus Valley, Gandhara, Islamic and Hindu art and architecture have overshadowed the study of jain archaeology. Purpose of the present paper is to share what we intend to do regarding the study of Jainism in Pakistan. No major work has been done for the systematic exploration, identification and documentation of the jain built heritage of Pakistan. The Department of Archaeology, University of the Punjab is taking this initiative for the first time to make detailed study of history of Jainism, its rise and decline. The study would highlight glory of the religion and contributions of its followers in social, cultural, economic, artistic and architectural fields. Comparative and analytical study of the jain archaeology would also be made keeping in view variety of the jain building traditions. Awareness among research scholars and local community would also be given to play their role for the preservation of Jain heritage scattered in different parts of Punjab as well as of Sindh province. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2008 Issue 3 CoJS Newsletter • March 2008 • Issue 3 Centre for Jaina Studies' Members _____________________________________________________________________ SOAS MEMBERS EXTERNAL MEMBERS Honorary President Paul Dundas Professor J Clifford Wright (University of Edinburgh) Vedic, Classical Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit Senior Lecturer in Sanskrit language and literature; comparative philology Dr William Johnson (University of Cardiff) Chair/Director of the Centre Jainism; Indian religion; Sanskrit Indian Dr Peter Flügel Epic; Classical Indian religions; Sanskrit drama. Jainism; Religion and society in South Asia; Anthropology of religion; Religion and law; South Asian diaspora. ASSOCIATE MEMBERS Professor Lawrence A. Babb John Guy Dr Daud Ali (Amherst College) (Metropolitan Mueum of Art) History of medieval South India; Chola courtly culture in early medieval India Professor Nalini Balbir Professor Phyllis Granoff (Sorbonne Nouvelle) (Yale University) Professor Ian Brown The modern economic and political Dr Piotr Balcerowicz Dr Julia Hegewald history of South East Asia; the economic (University of Warsaw) (University of Heidelberg) impact of the inter-war depression in South East Asia Nick Barnard Professor Rishabh Chandra Jain (Victoria and Albert Museum) (Muzaffarpur University) Dr Whitney Cox Sanskrit literature and literary theory, Professor Satya Ranjan Banerjee Professor Padmanabh S. Jaini Tamil literature, intellectual (University of Kolkata) (UC Berkeley) and cultural history of South India, History of Saivism Dr Rohit Barot Dr Whitney M. Kelting (University of Bristol) (Northeastern University Boston) Professor Rachel Dwyer Indian film; Indian popular culture; Professor Bhansidar Bhatt Dr Kornelius Krümpelmann Gujarati language and literature; Gujarati (University of Münster) (University of Münster) Vaishnavism; Gujarati diaspora; compara- tive Indian literature.