Theatricality of Naumachiae Bachelor’S Diploma Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman Entertainment

Roman Entertainment The Emergence of Permanent Entertainment Buildings and its use as Propaganda David van Alten (3374912) [email protected] Bachelor thesis (Research seminar III ‘Urbs Roma’) 13-04-2012 Supervisor: Dr. S.L.M. Stevens Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 1: The development of permanent entertainment buildings in Rome ...................................... 9 1.1 Ludi circenses and the circus ............................................................................................ 9 1.2 Ludi scaenici and the theatre ......................................................................................... 11 1.3 Munus gladiatorum and the amphitheatre ................................................................... 16 1.4 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 19 2: The uncompleted permanent theatres in Rome during the second century BC ................. 22 2.0 Context ........................................................................................................................... 22 2.1 First attempts in the second century BC ........................................................................ 22 2.2 Resistance to permanent theatres ................................................................................ 24 2.3 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... -

Waters of Rome Journal

TIBER RIVER BRIDGES AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANCIENT CITY OF ROME Rabun Taylor [email protected] Introduction arly Rome is usually interpreted as a little ring of hilltop urban area, but also the everyday and long-term movements of E strongholds surrounding the valley that is today the Forum. populations. Much of the subsequent commentary is founded But Rome has also been, from the very beginnings, a riverside upon published research, both by myself and by others.2 community. No one doubts that the Tiber River introduced a Functionally, the bridges in Rome over the Tiber were commercial and strategic dimension to life in Rome: towns on of four types. A very few — perhaps only one permanent bridge navigable rivers, especially if they are near the river’s mouth, — were private or quasi-private, and served the purposes of enjoy obvious advantages. But access to and control of river their owners as well as the public. ThePons Agrippae, discussed traffic is only one aspect of riparian power and responsibility. below, may fall into this category; we are even told of a case in This was not just a river town; it presided over the junction of the late Republic in which a special bridge was built across the a river and a highway. Adding to its importance is the fact that Tiber in order to provide access to the Transtiberine tomb of the river was a political and military boundary between Etruria the deceased during the funeral.3 The second type (Pons Fabri- and Latium, two cultural domains, which in early times were cius, Pons Cestius, Pons Neronianus, Pons Aelius, Pons Aure- often at war. -

Urban Fabric: the Built Environment

CHAPTER 3. URBAN FABRIC: THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT On Christmas Eve a young man with long hair and luxurious clothes inlaid with jewels kneels in prayer on a deep red stone disk laid in the floor of Saint Peter’s Basilica. The Pope lifts a golden crown from the altar and places it on the man’s bowed head and the throng of spectators shouts, “To Charles the August, crowned by God, great and pacific emperor, long life and victory!” URBAN FABRIC: THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT 55 With this coronation in the year 800 the Holy Roman Empire was born, and, although the young French king did not use the title, Charlemagne is considered its first Emperor. His coro- nation brought some political stability to Europe and some of the first significant artistic activity in Rome since its fall. In fact, some historians, such as Kenneth Clark and Richard Krautheimer, invoking the Latin name for Charles, Carolus, have termed the period that follows the “Carolingian Renais- sance.” If you left St. Peter’s Basilica after the coronation, say to walk to your home on the Esquiline, you would have seen a city sur- prisingly similar to that of the height of the empire. Of course, the city had been devastated by numerous invasions which had stripped buildings of their valuable artworks and often left them roofless, open to the elements. Nevertheless, the basic building shapes were recognizable. Leaving St. Peter’s in the direction of the Colosseum you would pass the Circus Flaminius, the Pan- theon, the Theatre of Pompey and then the Baths of Agrippa. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Naumachie De Titus” Gérald Cariou

Projet ”Naumachie de Titus” Gérald Cariou To cite this version: Gérald Cariou. Projet ”Naumachie de Titus”. Virtual Retrospect 2003, Robert Vergnieux, Nov 2003, Biarritz, France. pp.44-50. hal-01741936 HAL Id: hal-01741936 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01741936 Submitted on 23 Mar 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Version en ligne Tiré-à-part des Actes du colloque Virtual Retrospect 2003 Biarritz (France) 6 et 7 novembre 2003 Vergnieux R. et Delevoie C., éd. (2004), Actes du Colloque Virtual Retrospect 2003, Archéovision 1, Editions Ausonius, Bordeaux G. Cariou Project “Titus Naumachia” . pp. 44-50 Conditions d’utilisation : l’utilisation du contenu de ces pages est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Tout autre utilisation est soumise à une autorisation préalable. Contact : [email protected] http://archeovision.cnrs.fr Virtual Retrospect 2003 November 6, 7 PROJET “NAUMACHIE DE TITUS” Gérald Cariou Centre de Recherche sur l’Antiquité et les Mythes (CERLAM) Maison de la Recherche en Sciences Humaines de Caen Basse-Normandie Université de Caen, Esplanade de la Paix 14032 Caen Cedex [email protected] Abstract : A team of scientists, artists and computer graphics Mots clés : Rome Antique – Naumachie – modélisation – designers are working on a short film showing the greatest images de synthèse. -

Term-List-For-Ch3b-Ancient-Roman-Theatre-2

Ancient Roman Theatre Cultural Periods and Events Theatrical Developments Persons Roman Kingdom Atellan & Greek influences Pompey Etruscan Rule Ludi Romani added plays Julius Caesar Roman Republic Ludi Florales included mime Mark Antony & Cleopatra Sabine invasion mime became pornographic Augustus (Octavian) Plebian Council reorganized ideals about not mixing comedy & Hadrian Tribal Assembly tragedy, 5 acts, 3 actors, moral Simon bar Kokhba Second & Third Punic Wars chorus, to profit & please Marcus Aurelius Third Servile War theatre buildings & arenas invented Commodus Jerusalem conquered arenas built across empire Elagabalus (Heliogabalus) Gaul conquered emperors as gladiators Diocletian crossing of the Rubicon slave & star actors/gladiators Justinian II Caesar assassinated loss of audience to the games Theodosius Roman Empire decline of theatre with Christian Plautus Great Fire of Rome condemnation, yet plays preserved in Jupiter & Mercury Vesuvius eruption the Byzantine (Eastern) Empire Terence Pantheon rebuilt Seneca bar Kokhba revolt Nero Pax Romana Horace Christians martyred Venus in temple watching toleration for Christians Christians sacrificed in arena Council of Nicaea gladiators (female) & hunters Constantine's two capitals referee with rudis Roman Empire as Christian stagehands as larvae, Mercury, Rome sacked Pluto, or Charon Western Empire collapsed musicians & clowns Byzantium conquered spectators with missilia senators, knights, & editor Commodus as Hercules dominus Perf. Types & Play Titles Performance Places & Spaces -

The Acts of Augustus As Recouded on the Monumentum Ancyranum

THE ACTS OF AUGUSTUS AS RECOUDED ON THE MONUMENTUM ANCYRANUM Below is a copy of the acts of the Deified Augustus by which he placed the whole world under the sovereignty of the Roman people, and of the amounts which he expended upon the state and the Roman people, as engraved upon two bronze colimins which have been set up in Rome.<» 1 . At the age of nineteen,* on my o>vn initiative and at my own expense, I raised an army " by means of which I restored Uberty <* to the republic, which the Mausoleum of Augustus at Rome. Its original form on that raonument was probably : Res gestae divi Augusti, quibus orbem terrarum imperio populi Romani subiecit, et impensae quas in rem publicam populumque Romanum fecit. " The Greek sup>erscription reads : Below is a translation of the acts and donations of the Deified Augustus as left by him inscribed on two bronze columns at Rome." * Octa\ian was nineteen on September -23, 44 b.c. « During October, by offering a bounty of 500 denarii, he induced Caesar's veterans at Casilinum and Calatia to enlist, and in Xovember the legions named Martia and Quarta repudiated Antony and went over to him. This activity of Octavian, on his own initiative, was ratified by the Senate on December 20, on the motion of Cicero. ' In the battle of Mutina, April 43. Augustus may also have had Philippi in mind. S45 Source: Frederick W. Shipley, Velleius Paterculus, Compendium of Roman History. Res Gestae Divi Augusti, LCL (Cambridge, MA: HUP, 19241969). THE ACTS OF AUGUSTUS, I. -

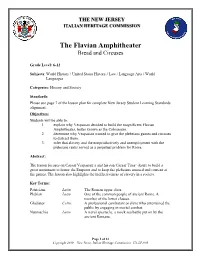

The Flavian Amphitheater Bread and Circuses

THE NEW JERSEY ITALIAN HERITAGE COMMISSION The Flavian Amphitheater Bread and Circuses Grade Level: 6-12 Subjects: World History / United States History / Law / Language Arts / World Languages Categories: History and Society Standards: Please see page 7 of the lesson plan for complete New Jersey Student Learning Standards alignment. Objectives: Students will be able to: 1. explain why Vespasian decided to build the magnificent Flavian Amphitheater, better known as the Colosseum. 2 determine why Vespasian wanted to give the plebeians games and circuses to distract them. 3. infer that slavery and the nonproductively and unemployment with the plebeians ranks served as a perpetual problem for Rome. Abstract: The lesson focuses on Caesar Vespasian’s and his son Caesar Titus’ desire to build a great monument to honor the Emperor and to keep the plebeians amused and content at the games. The lesson also highlights the ineffectiveness of slavery in a society. Key Terms: Patricians Latin The Roman upper class. Plebian Latin One of the common people of ancient Rome. A member of the lower classes. Gladiator Celtic A professional combatant or slave who entertained the public by engaging in mortal combat. Naumachia Latin A naval spectacle; a mock sea battle put on by the ancient Romans. Page 1 of 13 Copyright 2019 – New Jersey Italian Heritage Commission U3-LP-005 Background: Early in the history of the Roman Republic, most common Romans farmed on small homesteads around the city. They also served in the army during Rome's numerous wars. As Roman conquests increased, the city began to employee a professional army and the patricians, or the upper class accumulated tremendous amounts of wealth. -

The Streets of Rome Walking Through the Streets of the Capital

Comune di Roma Tourism The streets of Rome Walking through the streets of the capital via dei coronari via giulia via condotti via sistina via del babuino via del portico d’ottavia via dei giubbonari via di campo marzio via dei cestari via dei falegnami/via dei delfini via di monserrato via del governo vecchio via margutta VIA DEI CORONARI as the first thoroughfare to be opened The road, whose fifteenth century charac- W in the medieval city by Pope Sixtus IV teristics have more or less been preserved, as part of preparations for the Great Jubi- passed through two areas adjoining the neigh- lee of 1475, built in order to ensure there bourhood: the “Scortecchiara”, where the was a direct link between the “Ponte” dis- tanners’ premises were to be found, and the trict and the Vatican. The building of the Imago pontis, so called as it included a well- road fell in with Sixtus’ broader plans to known sacred building. The area’s layout, transform the city so as to improve the completed between the fifteenth and six- streets linking the centre concentrated on teenth centuries, and its by now well-es- the Tiber’s left bank, meaning the old Camp tablished link to the city centre as home for Marzio (Campus Martius), with the northern some of its more prominent residents, many regions which had risen up on the other bank, of whose buildings with their painted and es- starting with St. Peter’s Basilica, the idea pecially designed facades look onto the road. being to channel the massive flow of pilgrims The path snaking between the charming and towards Ponte Sant’Angelo, the only ap- shady buildings of via dei Coronari, where proach to the Vatican at that time. -

Roman Colosseum Newsletter

The Roman Colosseum A massive stone amphitheater located just East of the Roman Forum is a Colosseum that was commissioned around 70-72 A.D. by Emperor Vespasian of the Flavian dynasty. It was a gift to the Roman people. The Emperor wanted to restore Rome to its former glory period prior to the turmoil of the recent civil war. Construction of the Colosseum began in 72 A.D. and was located on the site that was once the lake and gardens of the Emperor Nero's Golden House. The lake was drained and a concrete foundation six meters deep was put down as a precaution against potential earthquakes. The Colosseum's original name was Amphiteatrum Flavium (Flavian Amphitheater). It opened for business in 80 A.D. in the reign of Titus, Vespasian's eldest son, with a 100 day gladiator spectacular. The Colosseum was finally completed in the reign of the other son, Domitian. The finished building was like nothing Romans had ever seen. It was the biggest building of its kind. Its features: Four stories Height of 150 feet Width of 620 Feet x 513 feet A roofed awning Capacity for 50,000 people 32 animal pens 80 entrances 36 trap doors Underground two-level Colosseum Architecture Measuring some 620 by 513 feet, the Colosseum was the largest amphitheater in the Roman world. It was a freestanding structure that spanned 6 acres of land. The distinctive exterior had three stories of arched entrances - a total of around 80-supported by semi-cicular columns. Each story contained columns of a diferent style. -

Colosseum As a Site of Ancient Roman Entertainment and Where the Different Social Classes of the Ancient Roman Society Sat

AimAim • I can describe the Colosseum as a site of Ancient Roman entertainment and where the different social classes of the Ancient Roman society sat. SuccessSuccess Criteria • •Statement I can explain 1 Lorem why ipsumAncient dolor Romans sit amet attended, consectetur the Colosseum. adipiscing elit. • •Statement I can explain 2 where the different social classes of the Ancient Roman society• Sub statement sat in the Colosseum. • I can explain the role of the Emperor and the senators in Ancient Roman society. • I can explain who the gladiators were and their role in relation to the Colosseum. A Roman Amphitheatre The Colosseum is a Roman amphitheatre. Its name in Latin was Amphitheatrum Flavium Romae. Latin was the language of the Roman Empire and many European languages spoken today, such as Spanish, French, Portuguese or Italian come from Latin. Attending the Colosseum was part of Ancient Roman life. Can you imagine why? A Place for Entertainment Ancient Romans liked to have fun, but they had a very different concept of fun to the way we amuse ourselves nowadays. For example, they enjoyed watching people fight against lions! They were also amused by watching gladiators fight to death. The Colosseum is the largest amphitheatre ever built. It had seating for 55,000 people! That’s as big as the Anfield Football Stadium in Liverpool. The best place, the Podium, or Tribune, was reserved for the Emperor and his family, as well as for the senators. The Emperor and the Senate The Emperor controlled the Roman Empire and had a very luxurious life with the best of everything. -

Nero Claudius Caesar (Nero) - the Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Volume 6

Nero Claudius Caesar (Nero) - The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 6. C. Suetonius Tranquillus Project Gutenberg's Nero Claudius Caesar (Nero), by C. Suetonius Tranquillus This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Nero Claudius Caesar (Nero) The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 6. Author: C. Suetonius Tranquillus Release Date: December 13, 2004 [EBook #6391] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NERO CLAUDIUS CAESAR *** Produced by Tapio Riikonen and David Widger THE LIVES OF THE TWELVE CAESARS By C. Suetonius Tranquillus; To which are added, HIS LIVES OF THE GRAMMARIANS, RHETORICIANS, AND POETS. The Translation of Alexander Thomson, M.D. revised and corrected by T.Forester, Esq., A.M. Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. NERO CLAUDIUS CAESAR. (337) I. Two celebrated families, the Calvini and Aenobarbi, sprung from the race of the Domitii. The Aenobarbi derive both their extraction and their cognomen from one Lucius Domitius, of whom we have this tradition: --As he was returning out of the country to Rome, he was met by two young men of a most august appearance, who desired him to announce to the senate and people a victory, of which no certain intelligence had yet reached the city. To prove that they were more than mortals, they stroked his cheeks, and thus changed his hair, which was black, to a bright colour, resembling that of brass; which mark of distinction descended to his posterity, for they had generally red beards.