THE ORIGIN of the GODS Incorporating the Ideas of Edward Furlong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology (2007)

P1: JzG 9780521845205pre CUFX147/Woodard 978 0521845205 Printer: cupusbw July 28, 2007 1:25 The Cambridge Companion to GREEK MYTHOLOGY S The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology presents a comprehensive and integrated treatment of ancient Greek mythic tradition. Divided into three sections, the work consists of sixteen original articles authored by an ensemble of some of the world’s most distinguished scholars of classical mythology. Part I provides readers with an examination of the forms and uses of myth in Greek oral and written literature from the epic poetry of the eighth century BC to the mythographic catalogs of the early centuries AD. Part II looks at the relationship between myth, religion, art, and politics among the Greeks and at the Roman appropriation of Greek mythic tradition. The reception of Greek myth from the Middle Ages to modernity, in literature, feminist scholarship, and cinema, rounds out the work in Part III. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology is a unique resource that will be of interest and value not only to undergraduate and graduate students and professional scholars, but also to anyone interested in the myths of the ancient Greeks and their impact on western tradition. Roger D. Woodard is the Andrew V.V.Raymond Professor of the Clas- sics and Professor of Linguistics at the University of Buffalo (The State University of New York).He has taught in the United States and Europe and is the author of a number of books on myth and ancient civiliza- tion, most recently Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult. Dr. -

David N. Talbott

David N. Talbott THE SATURN MYTH A reinterpretation of rites and symbols illuminating some of the dark corners of primordial society Intrigued by Velikovsky’s claim that Saturn was once the pre-eminent planetary god, David Talbott resolved to examine its mythical character. “I wanted to know,” he wrote, “if ancient sources had a coherent story to tell about the planet . I had no inkling of the spectacular tale hidden in the chronicles.” In this startling re-interpretation of age-old symbolism Talbott argues that the “Great God” or “Universal Monarch” of the ancients was not the sun, but Saturn, which once hung ominously close to the earth, and visually dominated the heavens. Talbott’s close textual and symbolic analysis reveals the fundamental themes of Saturn imagery and proves that all of them—including the “cosmic ship”, the “island at the top of the world”, the “eye of heaven” and “the revolving temple” were based on celestial observations in the northern sky. In addition he shows how such diverse symbols as the Cross, “sun”-wheels, holy mountains, crowns of royalty and sacred pillars grew out of ancient Saturn worship. Talbott contends that Saturn's appearance at the time, radically different from today, inspired man's leap into civilization, since many aspects of early civilization can be seen as conscious efforts to re-enact or commemorate Saturn’s organization of his “celestial” kingdom. A fascinating look at ancient history and cosmology, The Saturn Myth is a provocative book that might well change the way you think about man’s history and the history of the universe. -

Plinius Senior Naturalis Historia Liber V

PLINIUS SENIOR NATURALIS HISTORIA LIBER V 1 Africam Graeci Libyam appellavere et mare ante eam Libycum; Aegyptio finitur, nec alia pars terrarum pauciores recipit sinus, longe ab occidente litorum obliquo spatio. populorum eius oppidorumque nomina vel maxime sunt ineffabilia praeterquam ipsorum linguis, et alias castella ferme inhabitant. 2 Principio terrarum Mauretaniae appellantur, usque ad C. Caesarem Germanici filium regna, saevitia eius in duas divisae provincias. promunturium oceani extumum Ampelusia nominatur a Graecis. oppida fuere Lissa et Cottae ultra columnas Herculis, nunc est Tingi, quondam ab Antaeo conditum, postea a Claudio Caesare, cum coloniam faceret, appellatum Traducta Iulia. abest a Baelone oppido Baeticae proximo traiectu XXX. ab eo XXV in ora oceani colonia Augusti Iulia Constantia Zulil, regum dicioni exempta et iura in Baeticam petere iussa. ab ea XXXV colonia a Claudio Caesare facta Lixos, vel fabulosissime antiquis narrata: 3 ibi regia Antaei certamenque cum Hercule et Hesperidum horti. adfunditur autem aestuarium e mari flexuoso meatu, in quo dracones custodiae instar fuisse nunc interpretantur. amplectitur intra se insulam, quam solam e vicino tractu aliquanto excelsiore non tamen aestus maris inundant. exstat in ea et ara Herculis nec praeter oleastros aliud ex narrato illo aurifero nemore. 4 minus profecto mirentur portentosa Graeciae mendacia de his et amne Lixo prodita qui cogitent nostros nuperque paulo minus monstrifica quaedam de iisdem tradidisse, praevalidam hanc urbem maioremque Magna Carthagine, praeterea ex adverso eius sitam et prope inmenso tractu ab Tingi, quaeque alia Cornelius Nepos avidissime credidit. 5 ab Lixo XL in mediterraneo altera Augusta colonia est Babba, Iulia Campestris appellata, et tertia Banasa LXXV p., Valentia cognominata. -

Greek Culture

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE GREEK CULTURE Course Description Greek Culture explores the culture of ancient Greece, with an emphasis on art, economics, political science, social customs, community organization, religion, and philosophy. About the Professor This course was developed by Frederick Will, Ph.D., professor emeritus from the University of Iowa. © 2015 by Humanities Institute Course Contents Week 1 Introduction TEMPLES AND THEIR ART Week 2 The Greek Temple Week 3 Greek Sculpture Week 4 Greek Pottery THE GREEK STATE Week 5 The Polis Week 6 Participation in the Polis Week 7 Economy and Society in the Polis PRIVATE LIFE Week 8 At the Dinner Table Week 9 Sex and Marriage Week 10 Clothing CAREERS AND TRAINING Week 11 Farmers and Athletes Week 12 Paideia RELIGION Week 13 The Olympian Gods Week 14 Worship of the Gods Week 15 Religious Scepticism and Criticism OVERVIEW OF GREEK CULTURE Week 16 Overview of Greek Culture Selected collateral readings Week 1 Introduction Greek culture. There is Greek literature, which is the fine art of Greek culture in language. There is Greek history, which is the study of the development of the Greek political and social world through time. Squeezed in between them, marked by each of its neighbors, is Greek culture, an expression, and little more, to indicate ‘the way a people lived,’ their life- style. As you will see, in the following syllabus, the ‘manner of life’ can indeed include the ‘products of the finer arts’—literature, philosophy, by which a people orients itself in its larger meanings—and the ‘manner of life’ can also be understood in terms of the chronological history of a people; but on the whole, and for our purposes here, ‘manner of life’ will tend to mean the way a people builds a society, arranges its eating and drinking habits, builds its places of worship, dispenses its value and ownership codes in terms of an economy, and arranges the ceremonies of marriage burial and social initiation. -

Biblical Chronology: Legend Or Science? the Ethel M

James Barr, Biblical Chronology: Legend Or Science? The Ethel M. Wood Lecture 1987. Delivered at the Senate House, University of London on 4 March 1987. London: University of London, 1987. Pbk. ISBN: 7187088644. pp.19. Biblical Chronology: Legend Or Science? James Barr, FBA Regius Professor of Hebrew, University of Oxford The Ethel M. Wood Lecture 1987 Delivered at the Senate House, University of London on 4 March 1987 [p.1] The subject of biblical chronology can be seen in two quite different ways. Firstly, there is scientific or historical chronology, which deals with the real chronology of actual events. This is the way in which the subject is approached in most current books, articles and encyclopaedias.1 You may ask, for instance, in what year Jesus was born, or in what year John the Baptist began his preaching; and the way to approach this is to consider the years in which Augustus or Tiberius was Roman emperor, in which Herod was king of Judaea, in which Quirinius conducted a census in Syria, and to try to set the relevant gospel stories in relation with these. If you were successful, you would end up with a date in years BC or AD, for example 4 BC which was long the traditional date for the birth of Jesus (since it was the year in which Herod the Great died), although most recent estimates end up with a date some years earlier.2 Or you might ask what was the year in which Solomon’s temple was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar, and you might produce the result of 586 BC, on the basis of historical data which could be mustered and verified historically. -

Chronology of Old Testament a Return to Basics

Chronology of the Old Testament: A Return to the Basics By FLOYD NOLEN JONES, Th.D., Ph.D. 2002 15th Edition Revised and Enlarged with Extended Appendix (First Edition 1993) KingsWord Press P. O. Box 130220 The Woodlands, Texas 77393-0220 Chronology of the Old Testament: A Return to the Basics Ó Copyright 1993 – 2002 · Floyd Nolen Jones. Floyd Jones Ministries, Inc. All Rights Reserved. This book may be freely reproduced in any form as long as it is not distributed for any material gain or profit; however, this book may not be published without written permission. ISBN 0-9700328-3-8 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... I am gratefully indebted to Dr. Alfred Cawston (d. 3/21/91), founder of two Bible Colleges in India and former Dean and past President of Continental Bible College in Brussels, Belgium, and Jack Park, former President and teacher at Sterling Bible Institute in Kansas, now serving as a minister of the gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ and President of Jesus' Missions Society in Huntsville, Texas. These Bible scholars painstakingly reviewed every Scripture reference and decision in the preparation of the Biblical time charts herewith submitted. My thanks also to: Mark Handley who entered the material into a CAD program giving us computer storage and retrieval capabilities, Paul Raybern and Barry Adkins for placing their vast computer skills at my every beckoning, my daughter Jennifer for her exhausting efforts – especially on the index, Julie Gates who tirelessly assisted and proofed most of the data, words fail – the Lord Himself shall bless and reward her for her kindness, competence and patience, and especially to my wife Shirley who for two years prior to the purchase of a drafting table put up with a dining room table constantly covered with charts and who lovingly understood my preoccupation with this project. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

A Glossary of Greek Birds

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA MEDICAL CENTER LIBRARY SAN FRANCISCO FROM THBJLreWTRY OF THE LATE PAN S. CODELLAS, M.D. rr^r s*~ - GLOSSARY OF GREEK BIRDS Bonbon HENRY FROWDE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE AMEN CORNER, E.G. MACMILLAN & CO., 66 FIFTH AVENUE Fro. I. FIG. 2. FIG. 3. FIG. FIG. 5. FIG. 6. FRONTISPIECE. ILLUSTRATIONS. i. PARTHIAN FIG. AN ARCHAIC GEM, PROBABLY (Paris Coll., 1264,2 ; cf. Imhoof-Blumer und Keller, PI. xxi, 14). FIG. 2. TETRADRACHM OF ERETRIA (B. M. Cat., Central Or., PI. xxiii, i). Both these subjects represent a bird on a bull's (or cow's) back, in my opinion the pleiad in relation to the sign Taurus (vide infra, p. 31). In 2 is to the in r it is in Fig. the bull turning round, symbolize tropic ; Fig. the conventional kneeling attitude of the constellation Taurus, as Aratus describes it (Ph. 517) Tavpov 5f ateeXfcov oaarj irepityaiveTai oK\a, or in Cicero's translation ' Atque genu flexo Taurus connititur ingens.' Compare also, among other kindred types, the coins of Paphos, showing a bull with the winged solar disc on or over his back {Rev. Num., 1883, p. 355; Head, H. Numorum, p. 624, &c.). FIGS. 3, 4. A COIN OF AGRIGENTUM, WITH EAGLE AND CRAB (Head, H. Niimorum, p. 105). Aquila, which is closely associated with i. as Cancer rises : it Capricorn (cf. Manil. 624), sets may figure, therefore, as a solstitial sign. FIG. 5. COIN OF HlMERA, BEFORE B.C. 842, WITH THE COCK (Head, cf. H. Numorum, p. 125 ; infra, p. 26). FIG. -

Arrian's Voyage Round the Euxine

— T.('vn.l,r fuipf ARRIAN'S VOYAGE ROUND THE EUXINE SEA TRANSLATED $ AND ACCOMPANIED WITH A GEOGRAPHICAL DISSERTATION, AND MAPS. TO WHICH ARE ADDED THREE DISCOURSES, Euxine Sea. I. On the Trade to the Eqft Indies by means of the failed II. On the Di/lance which the Ships ofAntiquity ufually in twenty-four Hours. TIL On the Meafure of the Olympic Stadium. OXFORD: DAVIES SOLD BY J. COOKE; AND BY MESSRS. CADELL AND r STRAND, LONDON. 1805. S.. Collingwood, Printer, Oxford, TO THE EMPEROR CAESAR ADRIAN AUGUSTUS, ARRIAN WISHETH HEALTH AND PROSPERITY. We came in the courfe of our voyage to Trapezus, a Greek city in a maritime fituation, a colony from Sinope, as we are in- formed by Xenophon, the celebrated Hiftorian. We furveyed the Euxine fea with the greater pleafure, as we viewed it from the lame fpot, whence both Xenophon and Yourfelf had formerly ob- ferved it. Two altars of rough Hone are ftill landing there ; but, from the coarfenefs of the materials, the letters infcribed upon them are indiftincliy engraven, and the Infcription itfelf is incor- rectly written, as is common among barbarous people. I deter- mined therefore to erect altars of marble, and to engrave the In- fcription in well marked and diftinct characters. Your Statue, which Hands there, has merit in the idea of the figure, and of the defign, as it reprefents You pointing towards the fea; but it bears no refemblance to the Original, and the execution is in other re- fpects but indifferent. Send therefore a Statue worthy to be called Yours, and of a fimilar delign to the one which is there at prefent, b as 2 ARYAN'S PERIPLUS as the fituation is well calculated for perpetuating, by thefe means, the memory of any illuftrious perfon. -

A Ritual for the Dead: the Tablets from Pelinna (L 7Ab)

CHAPTER TWO A RITUAL FOR THE DEAD: THE TABLETS FROM PELINNA (L 7AB) Translation of tablets L 7ab from Pelinna The two tablets from Pelinna (L 7a and 7b) were found in Thessaly in 1985, on the site of ancient Pelinna or Pelinnaion. They were placed on the breast of a dead female, in a tomb where a small statue of a maenad was also found (cf. a similar gure in App. II n. 7). Published in 1987, they revolutionized what had been known and said until then about these texts, and contributed new and extremely important view- points.1 They are in the shape of an ivy leaf, as they are represented on vase paintings,2 although it cannot be ruled out that they may represent a heart, in the light of a text by Pausanias that speaks of a “heart of orichalcum” in relation to the mysteries of Lerna.3 Everything in the grave, then, including the very form of the text’s support, suggests a clearly Dionysiac atmosphere, since both the ivy and the heart evoke the presence of the power of Dionysus. The text of one of the tablets is longer than that of the other. It has been suggested4 that the text of the shorter tablet was written rst, and since the entire text did not t, the longer one was written. We present the text of the latter:5 1 These tablets were studied in depth by their \ rst editors Tsantsanoglou-Parássoglou (1987) 3 ff., and then by Luppe (1989), Segal (1990) 411 ff., Graf (1991) 87 ff., (1993) 239 ff., Ricciardelli (1992) 27 ff., and Riedweg (1998). -

The Panel Abstracts

The Outskirts of Iambos Panel Proposal While the genre of Iambos is most commonly thought of as an archaic Greek phenomenon, iambic poetics seems to rear its ugly head throughout classical antiquity and beyond. In the typical literary-historical accounts, Iambos proper is deployed to describe the work of Archilochus, Hipponax, Semonides and other, more shadowy characters who inhabit the archaic Greek poetic landscape. Those poets who do compose iambic verses in later periods, e.g., Callimachus, Horace, etc., are seen purely as imitators or adapters—their archaic models contribute significantly to the interpretation of their iambic poetry. Of course, in the case of Callimachus and Horace, this derivative status is based on the poets' own words (cf. Call. Ia. 1.1- 4 and Hor. Ep. 1.19.23-25). The question arises, then, why focus attention on the derivative nature of a poem? Is this simply a symptom of the anxiety of influence or does it have a more integral role to play in the iambic mode? Given the liminal character of the archaic Greek iambographers, this panel examines such derivativeness as constitutive aspect of Iambos from the earliest period. In short, the archaic Greek iambographers tendency to showcase, in their poetry, their own faults and failings, their distance from Greek cultural and poetic norms, can be seen as an essential feature of the iambic mode and, as such, is used and transformed in subsequent iambicizing texts. This panel will investigate the implications of this self-consciously distant aspect of iambic poetics by looking for ways in which the iambic mode is marshaled in texts that seemingly lie outside the purview of what is traditionally considered authentic Iambos (i.e., limited to that composed in archaic Greece). -

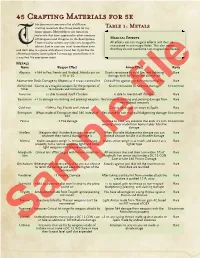

45 Crafting Materials for 5E His Document Contains a List of Different Crafting Materials That I Have Made for My Table 1: Metals Home Games

45 Crafting Materials for 5e his document contains a list of different crafting materials that I have made for my Table 1: Metals home games. Most of these are based on materials that have appeared in other versions of Dungeons and Dragons. In the descriptions, Magical Effects I have tried to remove any reference to specific All effects are non-magical effects and thus are Tplanes. Just in case you want to use them as-is maintained in anti-magic fields. This also means and don't play in a game with planar travel, but if you like the that they do not overcome non-magical resistances effects but not the descriptions I encourage you to flavor it in a way that fits your game most. Metals Name Weapon Effect Armor Effect Rarity Abyssus +1d4 to Fey, Fiends and Undead, Attacks crit on Grants resistance to cold, fire, and lightning Rare a 19 or 20 damage dealt by fiends and elementals Adamantine Deals Damage to Objects as if it was a critical hit Critical Hits against you turn into normal hits Rare Alchemical Counts as a magical weapon for the purposes of Grants resistance to Necrotic damage Uncommon Silver resistances and immunities Aururum Is able to mend itself if broken Is able to mend itself if broken Rare Baatorium +1 to damage on slashing and piercing weapons Resistance to slashing and piercing damage from Rare non-magical weapons Cold Iron +1d4 to Fey, Fiends and Undead Grants advantage on saves vs Spells Rare Entropium Whips made of Entropium deal 1d6 instead of Resistance to non-magical bludgeoning damage Uncommon 1d4 Fevrus +1 Fire damage Immune to Cold, any creature that ends it’s turn Uncommon wearing armor made from Fevrus takes 1d6 Fire damage.