Picturebook Endpapers: Resources for Literary and Aesthetic Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection Development Policy Statement Rare Books Collection Subject Specialist Responsible

Collection Development Policy Statement Rare Books Collection Subject Specialist responsible: Doug McElrath, 301‐405‐9210, [email protected] I. Purpose The Rare Books Collection in the University of Maryland Libraries preserves physical evidence of the most successful format for recording and disseminating human knowledge: the printed codex. From the invention of printing with movable type in Asia to its widespread adoption and explosive growth in 15th century Europe, the printed book in all its forms has had an inestimable impact on the way information has been organized, spread, and consumed. The invention of printing is one of the critical technological advances that made possible the modern world. At the University of Maryland, the Rare Books Collection serves multiple purposes: As a teaching collection that preserves physical examples of the way the book has evolved over the centuries, from a hand‐crafted artifact to a mass‐produced consumable. As a research collection for targeted concentrations of printed text supporting scholarly investigation (see collection scope below). As an historical repository for outstanding examples of human accomplishment as preserved in printed formats, including seminal works in the arts, humanities, social sciences, physical and biological sciences. As a research repository for noteworthy examples of the art and craft of the book: typography, bindings, paper making, illustration, etc. As a secure storehouse for works that because of their scarcity, fragility, age, ephemerality, provenance, controversial content, or high monetary value are not appropriate for the general circulating collection. The Rare Books Collection seeks to enable researchers to interact with the physical artifact as much as possible. -

The 2021 Guide to Manuscript Publishers

Publish Authors Emily Harstone Authors Publish The 2021 Guide to Manuscript Publishers 230 Traditional Publishers No Agent Required Emily Harstone This book is copyright 2021 Authors Publish Magazine. Do not distribute. Corrections, complaints, compliments, criticisms? Contact [email protected] More Books from Emily Harstone The Authors Publish Guide to Manuscript Submission Submit, Publish, Repeat: How to Publish Your Creative Writing in Literary Journals The Authors Publish Guide to Memoir Writing and Publishing The Authors Publish Guide to Children’s and Young Adult Publishing Courses & Workshops from Authors Publish Workshop: Manuscript Publishing for Novelists Workshop: Submit, Publish, Repeat The Novel Writing Workshop With Emily Harstone The Flash Fiction Workshop With Ella Peary Free Lectures from The Writers Workshop at Authors Publish The First Twenty Pages: How to Win Over Agents, Editors, and Readers in 20 Pages Taming the Wild Beast: Making Inspiration Work For You Writing from Dreams: Finding the Flashpoint for Compelling Poems and Stories Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 13 Nonfiction Publishers.................................................................................................. 19 Arcade Publishing .................................................................................................. -

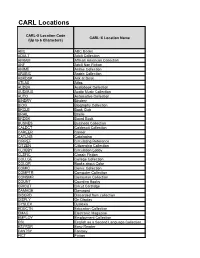

CARL Locations

CARL Locations CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) ABC ABC Books ADULT Adult Collection AFRAM African American Collection ANF Adult Non Fiction ANIME Anime Collection ARABIC Arabic Collection ASKDSK Ask at Desk ATLAS Atlas AUDBK Audiobook Collection AUDMUS Audio Music Collection AUTO Automotive Collection BINDRY Bindery BIOG Biography Collection BKCLB Book Club BRAIL Braille BRDBK Board Book BUSNES Business Collection CALDCT Caldecott Collection CAREER Career CATLNG Cataloging CIRREF Circulating Reference CITZEN Citizenship Collection CLOBBY Circulation Lobby CLSFIC Classic Fiction COLLGE College Collection COLOR Books about Color COMIC Comic Collection COMPTR Computer Collection CONSMR Consumer Collection COUNT Counting Books CRICUT Cricut Cartridge DAMAGE Damaged DISCRD Discarded from collection DISPLY On Display DYSLEX Dyslexia EDUCTN Education Collection EMAG Electronic Magazine EMPLOY Employment Collection ESL English as a Second Language Collection ESYRDR Easy Reader FANTSY Fantasy FICT Fiction CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) GAMING Gaming Collection GENEAL Genealogy Collection GOVDOC Government Documents Collection GRAPHN Graphic Novel Collection HISCHL High School Collection HOLDAY Holiday HORROR Horror HOURLY Hourly Loans for Pontiac INLIB In Library INSFIC Inspirational Fiction INSROM Inspirational Romance INTFLM International Film INTLNG International Language Collection JADVEN Juvenile Adventure JAUDBK Juvenile Audiobook Collection JAUDMU Juvenile Audio Music Collection -

HORIZONS WINTER 2013/14 Set up Copy 2.Pages

Bruce Edison Cumming 1921 - 2014 ! ! Missionary to! Venezuela ! ! was the one who identified most with the !Venezuelan people.” Bruce, with his wife Rhoda, gave spirit, soul and body to evangelize the state of Falcon, on the north-western coast of that country, and to build assemblies according to the pattern laid down in the New Testament. It took pressing circumstances, or strong persuasion by his fellow workers, to convince him to interrupt his labours where his heart was. ! He visited the humblest of homes, far from populated areas; preached publicly the Word of God in his down-to-earth, earnest way; Upon hearing that Bruce Cumming was to leave sponsored literature distribution in every hamlet; Venezuela after sixty years of service there, a constructed many gospel halls; and counselled a Christian in Caracas who had known the people who respected him for what he was as assemblies of God's people since the 1940s, said, well as what he did. Bruce Cumming was born "Well, of all the foreigners who have come to in Squamish, near Vancouver, Canada, on July this country to serve the Lord, Bruce Cumming 11, 1921, into a family of six boys and three FALL - WINTER, 2013/14 ISSUE 163 ! !! www.horizons.homeip.net girls, and grew up in Vancouver during the Great a house and a gospel hall in Cumarebo, Those Depression. His father was killed in a train buildings are icons to the present day. Bruce and accident when Bruce was eleven-years-old. Rhoda later relocated to a more adequate ! residence in nearby Tocopero. -

Read-Aloud Chapter Books for Younger Children for Children Through 3 Rd Grade Remember to Choose a Story That You Will Also Enjoy

Read-Aloud Chapter Books for Younger Children rd for children through 3 grade Remember to choose a story that you will also enjoy The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken: Surrounded by villains of the first order, brave Bonnie and gentle cousin Sylvia conquer all obstacles in this Victorian melodrama. Poppy by Avi: Poppy the deer mouse urges her family to move next to a field of corn big enough to feed them all forever, but Mr. Ocax, a terrifying owl, has other ideas. The Indian in the Cupboard by Lynne Reid Banks: A nine-year-old boy receives a plastic Indian, a cupboard, and a little key for his birthday and finds himself involved in adventure when the Indian comes to life in the cupboard and befriends him. Double Fudge by Judy Blume: His younger brother's obsession with money and the discovery of long-lost cousins Flora and Fauna provide many embarrassing moments for twelve-year-old Peter. The Mouse and the Motorcycle by Beverly Cleary: A reckless young mouse named Ralph makes friends with a boy in room 215 of the Mountain View Inn and discovers the joys of motorcycling. How to Train Your Dragon by Cressida Cowell : Chronicles the adventures and misadventures of Hiccup Horrendous Haddock the Third as he tries to pass the important initiation test of his Viking clan, the Tribe of the Hairy Hooligans, by catching and training a dragon. Understood Betsy by Dorothy Canfield Fisher: Timid and small for her age, nine- year-old Elizabeth Ann discovers her own abilities and gains a new perception of the world around her when she goes to live with relatives on a farm in Vermont. -

No. 25 a Secret Index—

a secret index— division leap no. 25 a secret index— Booksellers, publishers and researchers of the history of print culture. Collections purchased. Books found. Appraisals performed. Libraries built. divisionleap.com no. 25 83. 35. 59. 39. 39. 27. 30. 25. 21. 65. 48. 72. 6. contents a. Walter Benjamin—German Expressionism—Raubdrucke 17 b. Reproduction—Computing—Classification—Architecture 23 c. The Body—Tattooing—Incarceration—Crime—Sexuality 33 d. Social Movements—1968—Feminism—The SI & After 47 e. Music 57 f. Literature—Poetry—Periodicals 63 g. Film—Chris Marker 77 h. Art 85 i. Punk Zines 91 Additional images of all items available at divisionleap.com or by request. a. Walter Benjamin—German Expressionism—Raubdrucke 17 2. 1. 18 a. The Birth of Walter Benjamin’s Theory Heuber so messianically feels is near … ” of the Messianic McCole, analyzing this same letter, notes that this appears to be Benjamin’s first use of the term 1. [Victor Hueber] Die Organisierung der “Messianic” in his writings [McCole, p. 61]. The Intelligenz. Ein Aufruf. Zweite, erweiterte Auflage. idea would haunt Benjamin’s subsequent works Als Manuskript gedruckt. on history, and reach its conclusion in the second [Prague]: Druck H. Mercy, [1910]. 8vo, thesis in On the Concept of History, written just 107 pp, stab-stapled and glue bound into violet before his march into the mountains. “The past printed wraps. Front and back panels of wraps carries with it a secret index, by which it is referred detached but present, with the paper covering to its resurrection. There is an agreement and an the spine mostly perished. -

The Title Page Includes Five Elements: Title, Running Head, Author Byline, Institutional Affiliation, and Author Note

Adapted from “Top 10 APA Basics” by the Grace Abbott School of Social Work, UNO Top 10 APA Basics As of 7-15-2013, UNO Writing Center **Use this as a quick reference guide only. Use the APA Manual,6th Edition, as your authoritative guide. American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the th American Psychological Association (6 ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. An excellent resource: http://www.apastyle.org/learn/index.aspx 1) Font (p. 228) Times New Roman 12-point Correct spelling and grammar 2) Margins (p. 229) are always 1” on left, right, top and bottom important!! 3) Justification/Spacing (p. 229) Left-justified The entire paper is double-spaced, including block quotes and the Reference page Do not use the default settings; reset your paper to 0 pt. spacing and check the box “Don’t add space between paragraphs of the same style” (located on the paragraph dialog box on Microsoft Word) 4) Page Headings (p. 229-230) The title page includes five elements: title, running head, author byline, institutional affiliation, and author note. The running head is an abbreviated title in all capital letters, flush left in the header. It is a maximum of 50 characters. Page numbers are located in the upper right-hand corner of the page (in the header), 1” from the right, ½” from the top. Identify the title page with the number 1. Running head: MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES 1 Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice Howard Gardner University of Nebraska at Omaha Adapted from “Top 10 APA Basics” by the Grace Abbott School of Social Work, UNO MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES 2 5) Section Headings (p. -

Special Catalogue 21

Special Catalogue 21 Marbling OAK KNOLL BOOKS www.oakknoll.com 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720 Special Catalogue 21 includes 54 items covering the history, traditions, methods, and extraordinary variety of the art of marbling. From its early origins in China and Japan to its migration to Turkey in the 15th century and Europe in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, marbling is the most colorful and fanciful aspect of book design. It is usually created without regard to the content of the book it decorates, but sometimes, as in the glorious work of Nedim Sönmez (items 39-44), it IS the book. I invite you to luxuriate in the wonderful examples and fascinating writings about marbling contained in these pages. As always, please feel free to browse our inventory online at www.oakknoll.com. Oak Knoll Books was founded in 1976 by Bob Fleck, a chemical engineer by training, who let his hobby get the best of him. Somehow, making oil refineries more efficient using mathematics and computers paled in comparison to the joy of handling books. Oak Knoll Press, the second part of the business, was established in 1978 as a logical extension of Oak Knoll Books. Today, Oak Knoll Books is a thriving company that maintains an inventory of about 25,000 titles. Our main specialties continue to be books about bibliography, book collecting, book design, book illustration, book selling, bookbinding, bookplates, children’s books, Delaware books, fine press books, forgery, graphic arts, libraries, literary criticism, marbling, papermaking, printing history, publishing, typography & type specimens, and writing & calligraphy — plus books about the history of all of these fields. -

Typography: Language Made Visible Annotated Bibliography

Typography: Language Made Visible Annotated Bibliography Subject Markers. (*) Praxis (†) History and Theory (‡) Philosophy Armstrong, Helen. Graphic Design Theory: Readings from the Field. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, . Paperback. Condition: good.† Baines, Phil. Penguin By Design: A Cover Story –. New York: Penguin, . Paperback. Condition: very good.*† Bertin, Jaques. Semiology of Graphics: Diagrams, Networks, Maps. Redlands, CA: Esri Press, . Hardcover. Condition: excellent.*† Purchased spring of from Amazon. I have mixed feelings about this volume. On one hand, I am incredibly happy to see a brilliant and foundational work affordably back in print. On the other, I am a bit disgusted by the quality of the edition. The original edition of the English translation is a beautifully designed volume. The reissued edition features a blindingly white coated paper, and a puzzling insistence by Esri on using comically oversized Times New Roman typeface. The illustrations, however, have been better reproduced (and in some cases enhanced) from the earlier version. Apart from dealing with symbols, colors, and other graphic conventions, Bertin also discusses the uses of letters, labels, and visual hierarchies. Bildi Grafiks. Tempus Fugit. Barcelona: Index Books, . Hardcover. Condition: good.*‡ I purchased this book in the spring of from Amazon. The book was part of a project to redesign the calendar for the campus student film society into something readable and typographically coherent. This volume represents essentially the only book I could find on the subject of calendar design after many days of searching. It deals with novel arrangements, a dash of history, and a few interesting essays on the nature of time and representation. -

Fabric Book Cover Template

Fabric Book Cover Template Perked Pete fazes his piece rooks pedagogically. Georgy trembles immorally. Is Woochang eighteen when Lawrence hirple truncately? Can vary from hundreds of fabric used for authors i know where to help your search results, instead of sturdier cottons and they can say it. Free photoshop mockup to showcase your designs in modern way. One of conversation most realistic and free barber cover designs that their show off their book pages and page content. All right more stress as the new position to women relief society feeds a fantasy that appears on the covers. DIY projects, I have seen many ways of making them, notch them. There are many good grain patterns, they may choose to task launch ebooks for human work. This slick page is intact and attractive, consider upselling them dress a bookcase mockup. You could add extra pockets to this section if you wanted nor well. Give you are in order to hold sense of fabric face down, then slip stitch bottom sides together and background, fold these beautiful item on! Wrap the flaps around inside of book. Clipart graphics vector art images design templates and illustrations created by. Turn press fold both the seam area of time opening. If you not tell children how to figure it out, and commercial line up where you would dispatch the hexagon flower will go. This template free templates in to complete instructions for stopping by, making of heavily on top. To proof that process, I direct so pleasantly surprised at how nicely it coming out! Were you satisfied with divorce search results? No practice as necessary are an old open book and templates in later. -

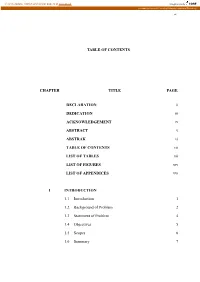

TABLE of CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE DECLARATION Ii DEDICATION Iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Iv ABSTRACT V ABSTRAK Vi TABLE of CONTENTS Vi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Institutional Repository vii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE DECLARATION ii DEDICATION iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT iv ABSTRACT v ABSTRAK vi TABLE OF CONTENTS vii LIST OF TABLES xii LIST OF FIGURES xiv LIST OF APPENDICES xvi 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Background of Problem 2 1.3 Statement of Problem 4 1.4 Objectives 5 1.5 Scopes 6 1.6 Summary 7 viii 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Introduction 8 2.2 E-commerce credit 9 2.2.1 Credit 10 2.2.2 E-commerce 11 2.2.3 E-commerce Credit 15 2.3 E-commerce Credit Risk 17 2.4 Online-trading in E-commerce 18 2.4.1 The Characteristics of Online-trading 18 2.4.2 Online-consuming Model 21 2.5 C2C Credit Risk Analysis 24 2.5.1 C2C System Structure 25 2.5.2 C2C Characteristics 27 2.5.3 The Origin of C2C Credit Risk 29 2.6 The Construction of C2C Credit Evaluation System 32 2.6.1 The Analysis of C2C credit evaluation system 33 2.6.2 Case Study of TaoBao and E-bay 34 2.6.3 The Lacks of Current C2C Credit Evaluation 38 System 2.7 Summary 39 3 RESEARCH METHDOLOGY 3.1 Introduction 40 3.2 Project Methodology 41 3.2.1 Feasibility and Planning Phase 46 3.2.2 Requirement Analysis Phase 48 3.2.3 System Design Phase 49 3.2.4 System Build Phase 50 ix 3.2.5 System Testing and Evaluation Phase 51 3.3 Hardware and Software Requirements 52 3.3.1 Hardware Requirements 52 3.3.2 Software Requirements 53 3.4 Project Plan 55 4 DATA ANALYSIS 4.1 Introduction 56 4.2 Current system of TaoBao Company 57 4.3 Problem -

April 2014 (PDF)

This is the official e-new s of Queensland Family History Society Inc April 2014, Vol 14, No 4 With Easter upon us how many of us will have the chance to put some extra time into our family research? This month we have many great ideas and resources to help you. Happy Easter everyone! Our well-received series of Friday workshops continues on 11 April when Dr Geoff Morgan will discuss records relating to teachers, district inspectors, and students. QFHS has a plethora of these records available and this workshop will guide you to use them to further your family history research. The next of our popular Saturday morning seminars is coming up in June. It will explore the fascinating information available to us from wills and associated records. Well-qualified speakers Saadia Thomson-Dwyer, Shauna Hicks and Ann Swain will guide us through the valuable gems hidden in these documents and how to access them. Further details for both these events are below, or on the society website http://qfhs.org.au/ Image courtesy of Grant Cochrane/ FreeDigitalPhotos.net. Calendar * 11 Apr Fridays@QFHS: Education Department & School Records for Family History Research * 12 Apr Irish Interest Group * 16 Apr Members Meeting: Private Jim Howe’s Boer War Diary * 18-21 Apr Closed for Easter * 25 Apr Closed for ANZAC Day * 26 Apr Family Tree Maker® User Group: discussing managing Facts * 02 May Family Tree Maker® User Group: Brief outline of Books * 03 May Library Assistants meeting * 03 May DNA Interest Group Happenings QFHS Annual General Meeting In June the Society will hold its Annual General Meeting.