Cacc 320/2016 [2020] Hkca 184 in the High Court of the Hong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHY HONG KONG Webinar Series

SPONSORS SUPPORTERS MEDIA PARTNER OGEMID WHY HONG KONG webinar series 31 MAY 2021 16:00 - 19:00 (GMT+8) The third edition of the ‘Why Hong Kong’ webinar series – ‘Why Use Hong Kong Law’ will provide major highlights of the substantive law of Hong Kong, presenting an in-depth and well-rounded analysis on the distinctive advantages of using Hong Kong law from different perspectives. Top-tier practitioners will be drawing on their solid experience to shed light upon the unique strengths of Hong Kong law in a broad spectrum of important areas ranging from litigation and restructuring to intellectual property, maritime and construction. Speakers will also bring to the fore unique aspects of Hong Kong law that provides unparalleled promising opportunities for worldwide companies and investors. Renowned for its solid yet transparent legal regime with an infinite number of business opportunities and exceptional dispute resolution service providers, Hong Kong shall remain a leading international business and dispute resolution hub for years to come. FREE REGISTRATION https://zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_FTNJ2Oc1Sv2eSYQvj9oi8g Enquiries For further details, please visit event website [email protected] https://aail.org/2021-why-use-hk-law/ TIME (GMT+8) PROGRAMME Welcome Remarks 16:00–16:05 • Ms Teresa Cheng GBS SC JP Secretary for Justice, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China Keynote Speech 16:05–16:25 • The Honourable Mr Justice Jeremy Poon Chief Judge of the High Court, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of -

Margaret Fong 方舜文 Melissa K

二零二一年七月 JULY 2021 HK$308 COVER STORY 封面專題 JULY 2021 2021 JULY Margaret 2021年7月 Fong Executive Director, Hong Kong Trade Development Council 方舜文 香港貿易發展局總裁 DATA PRIVACY 個人資料私隱 SECURITIES LAW 證券法 CIVIL PROCEDURE 民事訴訟程序 Limiting Disclosure of Personal Analysis of The Exchange’s Reform of Submitting to the Jurisdiction Data in the Companies Register the Main Board Profit Requirement – 接受司法管轄 Will Help Curb Doxxing Right Time for Hong Kong To Move On? 限制公司登記冊披露個人資料 港交所改革主板盈利規定之分析 —— 將有助遏止「起底」 香港改革是否正當其時? 100 95 75 25 5 0 Hong Kong Lawyer 香港律師 www.hk-lawyer.org The official journal of The Law Society of Hong Kong (incorporated with limited liability) 香港律師會 (以有限法律責任形式成立) 會刊 www.hk-lawyer.org Editorial Board 編輯委員會 Chairman 主席 Huen Wong 王桂壎 Nick Chan 陳曉峰 Inside your July issue Peter CH Chan 陳志軒 七月期刊內容 Charles CC Chau 周致聰 Michelle Cheng 鄭美玲 Heidi KP Chu 朱潔冰 Julianne P Doe 杜珠聯 3 EDITOR’S NOTE 編者的話 Elliot Fung 馮以德 Warren P Ganesh 莊偉倫 4 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 會長的話 Julienne Jen 任文慧 Karen Lam 藍嘉妍 6 CONTRIBUTORS 投稿者 Bernard Yue 余志匡 Stella SY Leung 梁淑儀 8 DISCIPLINARY DECISION 紀律裁決 Sauw Yim 蕭艷 Adamas KS Wong 黃嘉晟 12 FROM THE SECRETARIAT 律師會秘書處資訊 Tony YH Yen 嚴元浩 15 FROM THE COUNCIL TABLE 理事會議題 THE COUNCIL OF THE LAW SOCIETY OF HONG KONG 17 COVER STORY 封面專題 香港律師會理事會 Face to Face with 專訪 President 會長 Margaret Fong 方舜文 Melissa K. Pang 彭韻僖 Executive Director, Hong Kong Trade 香港貿易發展局總裁 Development Council Vice Presidents 副會長 Amirali B. Nasir 黎雅明 23 LAW SOCIETY NEWS 律師會新聞 Brian W. Gilchrist 喬柏仁 C. M. Chan 陳澤銘 28 NOTARIES NEWS 香港國際公證人協會新聞 Council Members 理事會成員 30 DATA PRIVACY 個人資料私隱 白樂德 Denis Brock Limiting Disclosure of Personal Data in 限制公司登記冊披露個人資料將 莊偉倫 Warren P. -

Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism

Emory International Law Review Volume 35 Issue 1 2021 Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism Shucheng Wang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Shucheng Wang, Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism, 35 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 21 (2021). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol35/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WANG_2.9.21 2/10/2021 1:03 PM HONG KONG’S CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE UNDER CHINA’S AUTHORITARIANISM Shucheng Wang∗ ABSTRACT Acts of civil disobedience have significantly impacted Hong Kong’s liberal constitutional order, existing as it does under China’s authoritarian governance. Existing theories of civil disobedience have primarily paid attention to the situations of liberal democracies but find it difficult to explain the unique case of the semi-democracy of Hong Kong. Based on a descriptive analysis of the practice of civil disobedience in Hong Kong, taking the Occupy Central Movement (OCM) of 2014 and the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (Anti-ELAB) movement of 2019 as examples, this Article explores the extent to which and how civil disobedience can be justified in Hong Kong’s rule of law- based order under China’s authoritarian system, and further aims to develop a conditional theory of civil disobedience for Hong Kong that goes beyond traditional liberal accounts. -

Members of the International Hague Network of Judges

on International Child Protection 35 Members of the International CANADA Hague Network of Judges The Honourable Justice Jacques CHAMBERLAND, Court of Appeal of Quebec (Cour d’appel du Québec), Montreal (Civil List as of November 2013 Law) ARGENTINA The Honourable Justice Robyn M. DIAMOND, Court of Queen’s Bench of Manitoba, Winnipeg (Common Law) Judge Graciela TAGLE, Judge of the City of Cordoba (Juez de la Ciudad de Córdoba), Córdoba CHILE AUSTRALIA Judge Hernán Gonzalo LÓPEZ BARRIENTOS, Judge of the Family Court of Pudahuel (Juez titular del Juzgado de Familia The Honourable Chief Justice Diana BRYANT, Appeal de Pudahuel), Santiago de Chile Division, Family Court of Australia, Melbourne (alternate contact) CHINA (Hong Kong, Special Administrative Region) The Honourable Justice Victoria BENNETT, Family Court of Australia, Commonwealth Law Courts, Melbourne (primary The Honourable Mr Justice Jeremy POON, Judge of the contact) Court of First Instance of the High Court, High Court, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region AUSTRIA Deputy High Court Judge Bebe Pui Ying CHU, Court of First Dr. Andrea ERTL, Judge at the District Court of Linz Instance, High Court, Hong Kong Special Administrative (Bezirksgericht Linz), Linz Region, Hong Kong BELGIUM COLOMBIA Ms Myriam DE HEMPTINNE, Magistrate of the Court of Doctor José Guillermo CORAL CHAVES, Magistrate of the Appeals of Brussels (Conseiller à la Cour d’appel de Bruxelles), Civil Family Chamber of the Superior Court for the Judicial Brussels District of Pasto (Magistrado de la Sala Civil Familia del Tribunal Superior del Distrito Judicial de Pasto), Pasto BELIZE COSTA RICA The Honourable Justice Michelle ARANA, Supreme Court Judge, Supreme Court of Belize, Belize City Mag. -

ACAH 2011 Official Conference Proceedings

The 2nd Asian Conference on Arts and Humanities Osaka, Japan, 2011 The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities Conference Proceedings 2011 For the International Academic Forum & The IAFOR International Advisory Board Professor Don Brash, Former Governor of the the New Professor Michiko Nakano, Waseda University, Tokyo, Zealand Reserve Bank & Former Leader of the National Japan Party, New Zealand Ms Karen Newby, Director, Par les mots solidaires, Lord Charles Bruce of Elgin and Kincardine, Lord Paris, France Lieutenant of Fife, Chairman of the Patrons of the National Galleries of Scotland & Trustee of the Historic Professor Michael Pronko, Meiji Gakuin University, Scotland Foundation, UK Tokyo, Japan Professor Tien-Hui Chiang, National University of Mr Michael Sakemoto, UCLA, USA Tainan, Chinese Taipei Mr Mohamed Salaheen, Country Director, UN World Mr Marcus Chidgey, CEO, Captive Minds Food Programme, Japan & Korea Communications Group, London, UK Mr Lowell Sheppard, Asia Pacific Director, HOPE Professor Steve Cornwell, Osaka Jogakuin University, International Osaka, Japan Professor Ken Kawan Soetanto, Waseda University, Professor Georges Depeyrot, Centre National de la Japan Recherche Scientifique/Ecole Normale Superieure, France His Excellency Dr Drago Stambuk, Croatian Professor Sue Jackson, Pro-Vice Master of Teaching Ambassador to Brazil and Learning, Birkbeck, University of London, UK Professor Mary Stuart, Vice-Chancellor of the Professor Michael Herriman, Nagoya University of University of Lincoln, UK Commerce and Business, Japan -

Sustainability Report 2015/16 BUILDING OUR SHARED FUTURE

Sustainability Report 2015/16 BUILDING OUR SHARED FUTURE Building Our Shared Future is about creating the physical and human capacity to enable us – Airport Authority Hong Kong, the airport community and the aviation industry – to meet Hong Kong’s growing demand for air transport, and thereby strengthen its social and economic development and sustain its long-term prosperity. BUILDING OUR SHARED FUTURE Building Our Shared Future is about creating the physical and human capacity to enable us – Airport Authority Hong Kong, the airport community and the aviation industry – to meet Hong Kong’s growing demand for air transport, and thereby strengthen its social and economic development and sustain its long-term prosperity. CONTENTS HOW TO READ THIS REPORT How to Read This Report 3 The structure of this report is stakeholder driven. To determine its THE BIG PICTURE content, we engaged with our employees, business partners, suppliers, tenants, non-governmental organisations, academics and other 2015/16 Sustainability in Essence 4 representatives of the Hong Kong community to better understand their interests and expectations as regards the sustainability initiatives and Chairman’s Message 6 performance of Airport Authority Hong Kong (AAHK). We have framed the report as a response to the most significant issues raised during Chief Executive Officer’s Message 8 the stakeholder focus groups. In addition, we have presented the direct views of our staff and quotes from external stakeholders to give a wider Our Approach to Sustainability 10 perspective on various sustainability issues and initiatives. To make the report easier to read and digest, it is divided into two main parts: HKIA at a Glance 14 ♦ The BIG PICTURE summarises our approach to sustainability and THEMATIC AREAS highlights our key achievements and initiatives for 2015/16. -

Cb(2)1574/03-04

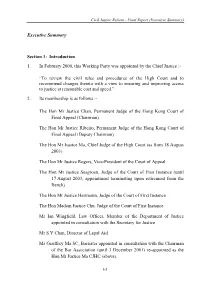

Civil Justice Reform - Final Report (Executive Summary) Executive Summary Section 1: Introduction 1. In February 2000, this Working Party was appointed by the Chief Justice :- “To review the civil rules and procedures of the High Court and to recommend changes thereto with a view to ensuring and improving access to justice at reasonable cost and speed.” 2. Its membership is as follows :- The Hon Mr Justice Chan, Permanent Judge of the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal (Chairman) The Hon Mr Justice Ribeiro, Permanent Judge of the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal (Deputy Chairman) The Hon Mr Justice Ma, Chief Judge of the High Court (as from 18 August 2003) The Hon Mr Justice Rogers, Vice-President of the Court of Appeal The Hon Mr Justice Seagroatt, Judge of the Court of First Instance (until 17 August 2003, appointment terminating upon retirement from the Bench) The Hon Mr Justice Hartmann, Judge of the Court of First Instance The Hon Madam Justice Chu, Judge of the Court of First Instance Mr Ian Wingfield, Law Officer, Member of the Department of Justice appointed in consultation with the Secretary for Justice Mr S Y Chan, Director of Legal Aid Mr Geoffrey Ma SC, Barrister appointed in consultation with the Chairman of the Bar Association (until 3 December 2001) re-appointed as the Hon Mr Justice Ma CJHC (above). E1 Civil Justice Reform - Final Report (Executive Summary) Mr Ambrose Ho SC, Barrister appointed in consultation with the Chairman of the Bar Association (as from 3 December 2001) Mr Patrick Swain, Solicitor appointed in consultation with the President of the Law Society Professor Michael Wilkinson, University of Hong Kong Mrs Pamela Chan, Chief Executive of the Consumer Council Master Jeremy Poon, Master of the High Court (Secretary) Mr Hui Ka Ho, Magistrate (Research Officer) 3. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(4)1162/18-19 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref: CB4/HS/1/18 Subcommittee on Proposed Senior Judicial Appointments Minutes of meeting held on Tuesday, 11 June 2019, at 10:45 am in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex Members present : Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, SBS, JP(Chairman) Hon Starry LEE Wai-king, SBS, JP Hon Steven HO Chun-yin, BBS Hon Frankie YICK Chi-ming, SBS, JP Hon Alice MAK Mei-kuen, BBS, JP Hon Dennis KWOK Wing-hang Dr Hon Fernando CHEUNG Chiu-hung Hon Alvin YEUNG Hon Jimmy NG Wing-ka, JP Dr Hon Junius HO Kwan-yiu, JP Hon Holden CHOW Ho-ding Hon YUNG Hoi-yan Hon CHAN Chun-ying, JP Members absent : Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Hon CHEUNG Kwok-kwan, JP Hon HUI Chi-fung Public Officers : Agenda item II attending Administration Wing, Chief Secretary for Administration's Office Ms Esther LEUNG, JP Director of Administration - 2 - Ms Jennifer CHAN, JP Deputy Director of Administration 2 Judiciary Administration Miss Emma LAU, JP Secretary Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission / Judiciary Administrator Mr Jock TAM Assistant Judiciary Administrator (Corporate Services) Clerk in attendance : Ms Shirley CHAN Chief Council Secretary (4)5 Staff in attendance : Mr Bonny LOO Assistant Legal Adviser 4 Ms Shirley TAM Senior Council Secretary (4)5 Ms Lauren LI Council Secretary (4)5 Ms Zoe TONG Legislative Assistant (4)5 Miss Mandy LUI Clerical Assistant (4)5 Action I. Election of Chairman Dr Priscilla LEUNG, the member who had the highest precedence among members present at the meeting, presided over the election of the Chairman. -

Edmilson Star of the Show As Duhail Lift Amir Cup Again

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Koepka grabs early lead with Ashghal total expenditure 63 as Tiger focused on roads and struggles highways until 2023: OBG published in QATAR since 1978 FRIDAY Vol. XXXX No. 11186 May 17, 2019 Ramadan 12, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Al Janoub Stadium in Wakrah opens to fanfare atar inaugurated its fi rst pur- pose-built stadium for the 2022 QWorld Cup yesterday, staging the prestigious Amir Cup fi nal in the 40,000-capacity Al Janoub (South) Stadium at Al Wakrah. The stadium, designed by late Brit- ish-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid and located south of Doha, erupted into cheers as Amir Cup fi nalists Al Sadd and Al Duhail ran onto the pitch. There were some traffi c jams and tight security checks as the ground, which was nearly full for the prestig- ious fi xture, began to fi ll ahead of kick- off . His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani tweeted on his verifi ed account ahead of kick- off that the ground’s name would be changed to ‘Al Janoub Stadium’ mean- ing ‘stadium of the south’. “I’ve travelled the world and I’ve been to stadiums in diff erent cities in- cluding the UK,” said Yousef al-Jaber, a His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani greets 35-year-old oil company research di- His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani is seen with FIFA President Gianni Infantino as they watch the match. spectators at the stadium. -

HKSAR V. CHAN CHUN CHUEN (30/10/2015, CACC233/2013)

HKSAR v. CHAN CHUN CHUEN (30/10/2015, CACC233/2013) Home | Go to Word | Print | CACC233/2013 IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION COURT OF APPEAL CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 233 OF 2013 (ON APPEAL FROM HCCC NO. 182 OF 2012) ____________ BETWEEN HKSAR Respondent and CHAN CHUN CHUEN (陳振聰) Applicant ____________ Before : Hon Lunn VP, Poon and Pang JJA in Court Date of Hearing : 17, 18, 21-24 September 2015 Date of Judgment : 30 October 2015 ________________________ J U D G M E N T ________________________ Hon Lunn VP (giving the Judgment of the Court) : 1. The applicant seeks leave to appeal against his conviction on 4 July 2013 after trial by Macrae J, as Macrae JA was then, and a jury of a count of forgery of the will of Nina Kung (Count 1), and a count of using that will (Count 2), contrary to sections 71 and 73 respectively of the Crimes Ordinance, Cap. 200 (the ‘Ordinance’). In addition, the applicant seeks leave to appeal against the sentence of 12 years’ imprisonment imposed on him by the judge in respect of each of the two counts, which sentences were ordered to be served concurrently. The indictment http://legalref.judiciary.gov.hk/lrs/common/ju/ju_frame.jsp?DIS=101120&currpage=T[30-Oct-2015 15:55:29] HKSAR v. CHAN CHUN CHUEN (30/10/2015, CACC233/2013) Count 1 2. The Particulars of Offence of Count 1 alleged that between 15 October 2006 and 8 April 2007 the applicant made a will of Nina Kung, to whom reference will be made by her married name Mrs Nina Wang, bearing the date of 16 October 2006: “ …. -

List of Attendees Africa

Standing International Forum of Commercial Courts The Standing International Forum of Commercial Courts Third Meeting Hosted virtually by the Supreme Court of Singapore List of Attendees Africa The Gambia Nigeria Uganda The Supreme Court of The Gambia Federal High Court of Nigeria Supreme Court of Uganda Hon. Chief Justice Hassan Jallow, Justice Ibrahim N. Buba Hon. Chief Justice Alfonse Owiny- Dollo, Chief Justice of The Gambia Chief Justice of Uganda Justice Nnamdi Dimgba The High Court of The Gambia Hon. Justice Stella Arach Amoko, Justice of the Supreme Court of Hon. Justice Zainab Jawara Alami, Sierra Leone Uganda Justice of the High Court of The Gambia Supreme Court of Sierra Leone Court of Appeal Kenya Hon. Chief Justice Hon. Justice Barishaki Cheborion, Babatunde Edwards, Justice of the Court of Appeal of Uganda High Court Chief Justice of the Republic of Sierra Leone High Court Hon. Lady Justice Mary Kasongo, Judge of the High Court Court of Appeal Hon. Justice Susan Abinyo, Judge of the Commercial Court Hon. Lord Justice Alfred Mabeya, Hon. Justice Allan B Halloway, Presiding Judge of the Commercial Justice of the Court of Appeal Hon. Justice Anne Bitature, & Tax Division of the High Court SIFoCC Judicial Observation High Court Programme participant 2021 Chief Magistrate Liz Gicheha Hon. Justice Lornard Taylor, Hon. Justice Boniface Wamala, Deputy Registrar Elizabeth Tanui; Justice of the High Court Judge of the High Court SIFoCC Judicial Observation Programme participant 2021 2 Asia People’s Republic of China Hong Kong SAR Japan Kazakhstan International Commercial Court of Hong Kong Judiciary (Participating as Observers) Supreme Court of Kazakhstan the Supreme People’s Court of the Hon. -

Curriculum Vitae of Mr Justice Jeremy Poon Shiu-Chor Justice of Appeal of the Court of Appeal of the High Court 1. Personal

Annex Curriculum Vitae of Mr Justice Jeremy Poon Shiu-chor Justice of Appeal of the Court of Appeal of the High Court 1. Personal Background Mr Justice Jeremy Poon Shiu-chor was born in Hong Kong in February 1962 (now 57). He is married and has two children. 2. Education Mr Justice Poon was educated in Hong Kong and in the United Kingdom. He obtained a Bachelor of Laws degree and a Postgraduate Certificate in Laws both from the University of Hong Kong in 1985 and 1986 respectively. He further acquired a Master of Laws degree from University of London in 1987. 3. Legal Experience Mr Justice Poon was called to the Hong Kong Bar in 1986. 4. Judicial Experience Mr Justice Poon was in private practice before joining the Judiciary as Magistrate in 1993. He was appointed Deputy Registrar, High Court in 1999 and Judge of the Court of First Instance of the High Court in 2006. He was appointed Justice of Appeal of the Court of Appeal of the High Court in 2015. Between 2011 and 2015, Mr. Justice Poon was the Civil Listing Judge, and the Judge in charge of the Probate List, the Family Law List and the Mental Health List in the Court of First Instance. In the Court of Appeal, Mr. Justice Poon hears civil, criminal and public law appeals. 5. Services and Activities related to the Legal Field Between 2000 and 2004 Secretary, Chief Justice’s Working Party on Civil Justice Reform Between 2012 and 2015 Chairman, Chief Justice’s Working Party on Family Procedure Rules, recommending the introduction of a unified procedure code for all family and matrimonial proceedings Since 2012 Member, Civil Court Users’ Committee 2013 In his capacity as the Probate Judge, Mr.