Global Shakespeare As a Tautological Myth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

177 © the Author(S) 2020 J. H. Pope, Shakespeare's Fans, Palgrave

INDEX1 NUMBERS AND SYMBOLS Amateur, 7, 8, 11, 16, 27, 46, 46n17, 10 Things I Hate About You, 26, 52, 54, 60, 69, 72, 72n14, 74, 33–63, 68, 108, 149 82–84, 87–89, 169 Anachronism, 26, 34, 122–124, 172 Anonymity, 120 A Anonymous, 71, 72, 91, 174 Actor, 2, 4, 8, 10, 20, 26, 28, 34, 46, Anti-fandom, 74, 173, 174, 174n9 48, 54, 58, 62, 79, 83, 104, 121, Anti-Midas, 55n57 124, 133–136, 136n4, 138–143, Appropriation, 33, 40n8, 67–69, 147–152, 148n37 81n47, 85 Adaptation, 9–11, 13–17, 19, Arcadia, 76 33, 36, 61, 67, 68, 77–79, Archive, 3, 24, 25, 71, 87, 100, 101, 80n45, 88–90, 94, 100, 103, 105, 108, 112, 114, 115, 119, 104, 107, 108, 110, 124, 127, 154, 169, 171, 171n3, 172 133, 148, 153, 162, 164, Archive of Our Own (AO3), 100, 171–173, 174n9 101, 110, 112, 113, 115, Affect, 26, 33–63, 85, 118 117n42, 119, 120, 128n62, 133, The Alchemist, 8 141, 145, 155, 163 All is True, 144 Aristophanes, 140 Allusion, 47, 61, 80, 107, Arthurian literature, 19 113, 116, 151, 153, 157, As You Like It, 79, 138, 159 159, 164 Atwood, Margaret, 17, 18 1 Note: Page numbers followed by ‘n’ refer to notes. © The Author(s) 2020 177 J. H. Pope, Shakespeare’s Fans, Palgrave Studies in Adaptation and Visual Culture, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33726-1 178 INDEX Austen, Jane, 23, 75, 115, 170–171 The Cobler of Preston (Charles Authenticity, 41, 54, 81, 106, 149, Johnson), 78 150, 154, 164 The Cobler of Preston (Christopher Authority, 16, 21, 27, 38, 39, 41–44, Bullock), 78 67, 70, 73, 74, 91, 92, 94, 95, Cohen, Ethan, 156 120, 152, 154n55, 162, 164, 170 Cohen, Joel, -

Browsing Through Bias: the Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies

Browsing through Bias: The Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies Sara A. Howard and Steven A. Knowlton Abstract The knowledge organization system prepared by the Library of Con- gress (LC) and widely used in academic libraries has some disadvan- tages for researchers in the fields of African American studies and LGBTQIA studies. The interdisciplinary nature of those fields means that browsing in stacks or shelflists organized by LC Classification requires looking in numerous locations. As well, persistent bias in the language used for subject headings, as well as the hierarchy of clas- sification for books in these fields, continues to “other” the peoples and topics that populate these titles. This paper offers tools to help researchers have a holistic view of applicable titles across library shelves and hopes to become part of a larger conversation regarding social responsibility and diversity in the library community.1 Introduction The neat division of knowledge into tidy silos of scholarly disciplines, each with its own section of a knowledge organization system (KOS), has long characterized the efforts of libraries to arrange their collections of books. The KOS most commonly used in American academic libraries is the Li- brary of Congress Classification (LCC). LCC, developed between 1899 and 1903 by James C. M. Hanson and Charles Martel, is based on the work of Charles Ammi Cutter. Cutter devised his “Expansive Classification” to em- body the universe of human knowledge within twenty-seven classes, while Hanson and Martel eventually settled on twenty (Chan 1999, 6–12). Those classes tend to mirror the names of academic departments then prevail- ing in colleges and universities (e.g., Philosophy, History, Medicine, and Agriculture). -

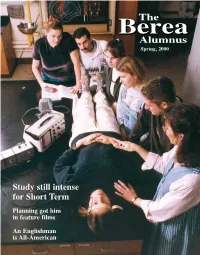

Study Still Intense for Short Term Planning Got Him in Feature Films

Spring, 2000 Study still intense for Short Term Planning got him in feature films An Englishman is All-American Editor’s Notes . Rod Bussey, ’63, Publisher Ed Ford, Fd ’54, Cx’58, Interim Editor Jackie Collier Ballinger, ’80, Managing Editor Shelley Boone Rhodus, ’85, Class Notes Editor The Berea Alumnus is published quarterly for Berea College alumni and friends by the Berea College Public Relations Department, CPO 2216, Berea, Ky. 40404. Periodical Postage paid at Berea, Ky. and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address corrections to Fukushima Keido (right), head of the Tofuku Temple in Kyoto, Japan, prepares a Japanese ink THE BEREA ALUMNUS, c/o Berea College painting banner at the recent Japan Semester Focus 2000 program sponsored by the Alumni Association, CPO 2203, Berea, Ky. International Center. 40404. Phone (859) 985-3104. ALUMNI ASSOCIATION STAFF Bringing the world to Berea—one of the major goals of the College’s Rod Bussey, ’63, Vice President for Alumni International Center—became a reality with the beginning of the Spring Term. Relations and Development Jackie Collier Ballinger, ’80, Executive Japanese arts, culture and history are included in an in-depth program that Director of Alumni Relations began in January and continues through May. Some of the highlights concerning Mary Labus, ’78, Associate Director the focus on Japan and its impact on the campus community are in Julie Shelley Boone Rhodus, ’85, Associate Director Melanie Conley Turner, ’94, Office Manager Sowell’s story that begins on page 8. Norma Proctor Kennedy, ’80, Secretary Motion picture actors have explored a variety of avenues in their quests to ALUMNI EXECUTIVE COUNCIL build film careers. -

When Culture Meets Couture Designer Lee Lapthorne to Create Bespoke Pieces of Furniture Inspired by Shakespeare

Press Release 7 January 2019 When Culture Meets Couture Designer Lee Lapthorne to create bespoke pieces of furniture inspired by Shakespeare One of the UK’s leading creative talents, Lee Lapthorne has been selected as the new Artist-in- Residence at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, the independent charity which cares for the five Shakespeare heritage sites in Stratford-upon-Avon, and promotes the enjoyment and understanding of his works, life and times. A prominent artist, fashion and textile designer, Lee Lapthorne will be creating two bespoke pieces of furniture inspired by the historic interiors of the Shakespeare houses and the Trust’s world-class museum and archive collection. They will go on display at Anne Hathaway’s Cottage and Hall’s Croft in Stratford-upon-Avon from 11 March – 15 September 2019. The Bard’s Rest Artist impression of The Bard’s Rest, by Lee Lapthorne The Bard’s Rest is a re-interpretation of a Greaves & Thomas pop-up sofa designed with bespoke textiles inspired by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust’s museum and archive collection, including intricate embroidery from a 16th century sweet purse, and the original rosette from David Garrick’s Shakespeare Jubilee of 1769*. The Bard’s Rest will be displayed in Hall’s Croft - the elegant Jacobean home of Shakespeare’s daughter Susanna, and her physician husband John Hall. The Love Settle Artist impression of The Love Settle, by Lee Lapthorne The Love Settle is an outdoor garden lounger bearing digital, screen-printed and embroidered weather-proof fabric inspired by love and romance in Shakespeare’s world. -

Selected Songs from "The Jubilee" (1769) Part Ofthe Colloquium on ((Shakespeare, Music, and Memory"

( () tv\ ~ lid c\ ~ sc Cv~ The University ofWashington School ofMusic )o{~ and the Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities present Gr ~ J-~ Selected songs from "The Jubilee" (1769) Part ofthe colloquium on ((Shakespeare, Music, and Memory" 29 April 2016 5:00 PM Brechemin Auditorium, UW School ofMusic UW Collegium Musicum Directed by J~Ann Taricani Tekla Cunningham, baroque violin John Lenti, baroque guitar Emerald Lessley, soprano Linda Tsatsanis, soprano Nathan Whittaker, baroque cello PROGRAM Texts by David Garrick (1717-1779) Music by Charles Dibdin (1745-1814) Texts provided in the slides are images from 18th-century publications of"The Jubilee" -'';"-. -- r~lZ~C01i:5/}CiV'ict:n;~-~:-~ ,.-~~=;' . -----~~.-.- ;....,_.--' Z. "Let Beauty with the Sun Arise" (duet) 3'.3 ~ "All this for a Poet?" (air) 2 ~ 0 S 4- "Ye Warwickshire Lads and Ye Lasses" (air) -'3>: s S' t'Sweet Willie 0" (air) 3,',/ Lf £; "Let us Sing It and Dance It" (duet) {: 13 -1- A Roundelay: "The Jubilee" (air) Lt" {g if "This, Sir, is a Jubilee" (duet) "The Jubilee" was a play produced by the Shakespearean actor David Garrick in October 1769. a month after his disastrous attempt to produce a three-day Shakespeare Jubilee in Stratford-upon-Avon in September 1769, which ended at mid-point because oftorrential rains and the flooding ofthe venue by the River Avon. Garrick departed Stratford in a fury and in debt, turning his vehemence into a satire ofthe Stratford event in his play "The Jubilee," performed over ninety times in the 1769-70 season at the Drury Lane Theatre in London. -

Terrorist and Organized Crime Groups in the Tri-Border Area (Tba) of South America

TERRORIST AND ORGANIZED CRIME GROUPS IN THE TRI-BORDER AREA (TBA) OF SOUTH AMERICA A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the Crime and Narcotics Center Director of Central Intelligence July 2003 (Revised December 2010) Author: Rex Hudson Project Manager: Glenn Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 205404840 Tel: 2027073900 Fax: 2027073920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ p 55 Years of Service to the Federal Government p 1948 – 2003 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Tri-Border Area (TBA) PREFACE This report assesses the activities of organized crime groups, terrorist groups, and narcotics traffickers in general in the Tri-Border Area (TBA) of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, focusing mainly on the period since 1999. Some of the related topics discussed, such as governmental and police corruption and anti–money-laundering laws, may also apply in part to the three TBA countries in general in addition to the TBA. This is unavoidable because the TBA cannot be discussed entirely as an isolated entity. Based entirely on open sources, this assessment has made extensive use of books, journal articles, and other reports available in the Library of Congress collections. It is based in part on the author’s earlier research paper entitled “Narcotics-Funded Terrorist/Extremist Groups in Latin America” (May 2002). It has also made extensive use of sources available on the Internet, including Argentine, Brazilian, and Paraguayan newspaper articles. One of the most relevant Spanish-language sources used for this assessment was Mariano César Bartolomé’s paper entitled Amenazas a la seguridad de los estados: La triple frontera como ‘área gris’ en el cono sur americano [Threats to the Security of States: The Triborder as a ‘Grey Area’ in the Southern Cone of South America] (2001). -

The Oxfordian Volume 21 October 2019 ISSN 1521-3641 the OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019

The Oxfordian Volume 21 October 2019 ISSN 1521-3641 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 The Oxfordian is the peer-reviewed journal of the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship, a non-profit educational organization that conducts research and publication on the Early Modern period, William Shakespeare and the authorship of Shakespeare’s works. Founded in 1998, the journal offers research articles, essays and book reviews by academicians and independent scholars, and is published annually during the autumn. Writers interested in being published in The Oxfordian should review our publication guidelines at the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship website: https://shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org/the-oxfordian/ Our postal mailing address is: The Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship PO Box 66083 Auburndale, MA 02466 USA Queries may be directed to the editor, Gary Goldstein, at [email protected] Back issues of The Oxfordian may be obtained by writing to: [email protected] 2 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 Acknowledgements Editorial Board Justin Borrow Ramon Jiménez Don Rubin James Boyd Vanessa Lops Richard Waugaman Charles Boynton Robert Meyers Bryan Wildenthal Lucinda S. Foulke Christopher Pannell Wally Hurst Tom Regnier Editor: Gary Goldstein Proofreading: James Boyd, Charles Boynton, Vanessa Lops, Alex McNeil and Tom Regnier. Graphics Design & Image Production: Lucinda S. Foulke Permission Acknowledgements Illustrations used in this issue are in the public domain, unless otherwise noted. The article by Gary Goldstein was first published by the online journal Critical Stages (critical-stages.org) as part of a special issue on the Shakespeare authorship question in Winter 2018 (CS 18), edited by Don Rubin. It is reprinted in The Oxfordian with the permission of Critical Stages Journal. -

China and Latin America and the Caribbean Building a Strategic Economic and Trade Relationship

China and Latin America and the Caribbean Building a strategic economic and trade relationship Osvaldo Rosales Mikio Kuwayama UNITED NATIONS China and Latin America and the Caribbean Building a strategic economic and trade relationship Osvaldo Rosales Mikio Kuwayama E C L n c Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) Santiago, April 2012 Libros de la CEPAL Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary Antonio Prado Deputy Executive Secretary Osvaldo Rosales Chief of the Division of International Trade and Integration Ricardo Pérez Chief of the Documents and Publications Division This document was prepared by Osvaldo Rosales and Mikio Kuwayama, Chief and Economic Affairs Officer, respectively, of the Division of International Trade and Integration of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Statistical support was provided by José Durán Lima and Mariano Alvarez, of the same Division. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Organization. Cover design: José Manuel Vélez United Nations publication ISBN: 978-92-1-021082-9 • E-ISBN: 978-92-1-055362-9 LC/G.2519-P Sales No. E.12.II.G.12 Copyright © United Nations, April 2012. All rights reserved Printed at United Nations, Santiago, Chile • 2011-914 Applications for the right to reproduce this work are welcomed and should be sent to the Secretary of the Publications Board, United Nations Headquarters, New York, N.Y. 10017, United States. Member States and the governmental institutions may reproduce this work without prior authorization, but are requested to mention the source and inform the United Nations of such reproduction. -

The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

THE KNOPF DOUBLEDAY PUBLISHING GROUP Autumn Rights Guide 2020 FICTION Jim Carrey & Dana Vachon, Memoirs and Misinformation 3 Tiffany McDaniel, Betty 5 Susan Conley, Landslide 7 Orville Schell, My Old Home 9 Jim Shepard, Phase Six 11 Bill Clinton & James Patterson, The President’s Daughter 13 Brittany Ackerman, The Brittanys 15 P.J. Vernon, Bath Haus 17 Omar El Akkad, What Strange Paradise 19 Ha Jin, A Song Everlasting 21 Timothy Schaffert, The Perfume Thief 23 FEATURED FICTION FROM THE BACKLIST Dorothy West, The Wedding 25 NON-FICTION Edward D. Melillo, The Butterfly Effect 27 Scott Anderson, The Quiet Americans 29 Peter Cozzens, Tecumseh and the Prophet 31 Tom Shone, The Nolan Variations 33 Bill Gates, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster 35 Joby Warrick, Red Line 36 Sharon Stone, The Beauty of Living Twice 38 Roya Hakakian, A Beginner’s Guide to America 39 Jenny Minton Quigley, Lolita in the Afterlife 41 Sharman Apt Russell, Within Our Grasp 43 Ian Manuel, My Time Will Come 45 Brian Castner, Stampede 47 Michael Dobbs, King Richard 49 M. Leona Godin, There Plant Eyes 51 Michael Sayman, App Kid 53 David Andrew Price, The Geniuses’ War 55 Helen Ellis, Bring Your Baggage and Don’t Pack Light 57 Tim Higgins, Power Play 59 Peter Robison, Flying Blind 61 Highlights from the Backlist 63 A New York Times Bestseller Memoirs and Misinformation A Novel Jim Carrey & Dana Vachon “A mad fever dream. Carrey and his collaborator Vachon pull out all the stops as their protagonist Jim Carrey careens from midlife blues through love and career complications toward the apocalypse . -

Greatest Living Playwright 8 February – 21 September 2014

Shakespeare: Greatest Living Playwright 8 February – 21 September 2014 In celebration of the 450th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s birth on 23 April 2014, this display will explore Shakespeare’s works as inspiration for a multitude of theatrical interpretations through the centuries and across the globe. Shakespeare: Greatest Living Playwright will take Shakespeare’s First Folio as its centrepiece. This collected edition of 36 of Shakespeare’s plays (excluding Pericles ) was published in 1623 and contains the first known versions of many of the plays. Without it, eighteen of the works would be unknown today, including Macbeth , The Tempest , and Twelfth Night . Surrounding the Folio will be new interviews, archive footage and photography, and twenty-five objects from the V&A collections, to explore how the plays have been interpreted and re-imagined by successive generations. At the heart of the display will be a specially commissioned audiovisual installation by Fifty Nine Productions featuring interviews with contemporary theatre practitioners. Leading actors, directors and designers will consider their relationships with Shakespeare’s plays, including Simon Russell Beale, Lucy Osborne, Edward Hall, Julie Taymor, Cush Jumbo, Sinéad Cusack and the Belarus Free Theatre. Illustrating the interviews will be recorded excerpts of Shakespearean performances from the V&A’s National Video Archive of Performance, and images from the Museum’s collections. This material will be projected onto a constellation of screens to represent the seeming infinity of interpretations of Shakespeare’s works. Objects on display, including props, costumes, set models, design sketches and printed ephemera, will illustrate past productions of Shakespeare’s works. -

HOW ARE THEIR NEEDS BEING MET? Submitted by Bernadette Anayah

DISSERTATION INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS AT COMMUNITY COLLEGES: HOW ARE THEIR NEEDS BEING MET? Submitted by Bernadette Anayah School of Education In partial fulfillment of requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2012 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: Linda Kuk Timothy Davies Nathalie Kees Deborah Young Copyright by Bernadette Anayah 2012 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS AT COMMUNITY COLLEGES: HOW ARE THEIR NEEDS BEING MET? An emerging trend today is the increased enrollment of international students at community colleges. International students look to American community colleges as a stepping stone to achieving an education that might otherwise be beyond their reach. They are attracted to the community college by the lower tuition costs, opportunities for guaranteed transfer to a four- year university, and the opportunity to study at a variety of geographical locations throughout the United States. California is one of the most popular destinations for international students in the United States. In 2011, more than 23,000 international students were enrolled in California’s 112 community colleges. The purpose of this qualitative study was to examine the experience of international students at selected California community colleges and explore how they perceive their needs and expectations are being met. Twenty nine international students from 19 countries were interviewed at seven California community colleges with small, medium, and large international student programs. The phenomenological interview was used as the primary method of data collection. The interview questions were open-ended and allowed the participants to discuss the wide and varied nature of their experience as international students at community colleges. -

Hamlet's Age and the Earl of Southampton

Hamlet’s Age and the Earl of Southampton Hamlet’s Age and the Earl of Southampton By Lars Kaaber Hamlet’s Age and the Earl of Southampton By Lars Kaaber This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Lars Kaaber All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9143-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9143-1 To Mikkel and Simon, two brilliant actors who can certainly do justice to Hamlet (and bring him to justice as well). TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Part I ............................................................................................................ 1 Hamlet’s Age Part II ......................................................................................................... 85 Hamlet and the Earl of Southampton Bibliography ............................................................................................ 147 Index ........................................................................................................ 153 PREFACE As Stuart M. Kurland quite correctly has observed, critics