1 Becoming Vaquero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

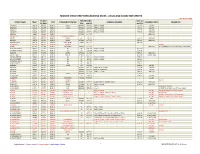

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

The Morgan's Role out West

THE MORGAN’S ROLE OUT WEST CELEBRATED AT VAQUERO HERITAGE DAYS 2012 By Brenda L. Tippin Stories of cowboys and the old west have always captivated Americans with their romance. The California vaquero was, in fact, America’s first cowboy and the Morgan horse was the first American breed regularly used by many of these early vaqueros. Renewed interest in the vaquero style of horsemanship in recent years has opened up huge new markets for breeders, trainers, and artisans, and the Morgan horse is stepping up to take his rightful place as an important part of California Vaquero Heritage. THE MORGAN CONNECTION and is becoming more widely recognized as what is known as the The Justin Morgan horse shared similar origins with the horses of “baroque” style horse, along with such breeds as the Andalusian, the Spanish conquistadors, who were the forefathers of the vaquero Lippizan, and Kiger Mustangs, which are all favored as being most traditions. The Conquistador horses, brought in by the Moors, like the horse of the Conquistadors. These breeds have the powerful, carried the blood of the ancient Barb, Arab, and Oriental horses— deep rounded body type; graceful arched necks set upright, coming the same predominant lines which may be found in the pedigree out of the top of the shoulder; and heavy manes and tails similar of Justin Morgan in Volume I of the Morgan Register. In recent to the European paintings of the Baroque period, which resemble years, the old style foundation Morgan has gained in popularity today’s original type Morgans to a remarkable degree. -

Stories of Words: Spanish

Stories of Words: Spanish By: Elfrieda H. Hiebert & Wendy Svec Stories of Words: Spanish, Second Edition © 2018 TextProject, Inc. Some rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-937889-23-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. “TextProject” and the TextProject logo are trademarks of TextProject, Inc. Cover photo ©2016 istockphoto.com/valentinrussanov. All rights reserved. Used under license. 2 Contents Learning About Words ...............................4 Chapter 1: Everyday Sayings .....................5 Chapter 2: ¡Buen Apetito! ...........................8 Chapter 3: Cockroaches to Cowboys ......12 Chapter 4: ¡Vámonos! ...............................15 Chapter 5: It’s Raining Gatos & Perros!....18 Our Changing Language ..........................21 Glossary ...................................................22 Think About It ...........................................23 3 Learning About Words Hola! Welcome to America, where you can see and hear the Spanish language all around you. Look at street signs or on menus. You will probably see Spanish words or names. Listen to the radio or television. It is likely you will hear Spanish being spoken. Since Spanish-speaking people first arrived in North America in the 16th century, the Spanish language has been part of American culture. Some people are being raised in Spanish-speaking homes and communities. Other people are taking classes to learn to speak and read Spanish. As a result, Spanish has become the second most spoken language in the United States. Every day, millions of Americans are speaking Spanish. -

Foreign Consular Offices in the United States

United States Department of State Foreign Consular Offices in the United States Spring/Summer2011 STATE DEPARTMENT ADDRESSEE *IF YOU DO NOT WISH TO CONTINUE RECEIVING THIS PUBLICATION PLEASE WRITE CANCEL ON THE ADDRESS LABEL *IF WE ARE ADDRESSING YOU INCORRECTLY PLEASE INDICATE CORRECTIONS ON LABEL RETURN LABEL AND NAME OF PUBLICATION TO THE OFFICE OF PROTOCOL, DEPARTMENT OF STATE, WASHINGTON, D.C. 20520-1853 DEPARTMENT OF STATE PUBLICATION 11106 Revised May 24, 2011 ______________________________________________________________________________ For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 FOREIGN CONSULAR OFFICES IN THE UNITED STATES i PREFACE This publication contains a complete and official listing of the foreign consular offices in the United States, and recognized consular officers. Compiled by the U.S. Department of State, with the full cooperation of the foreign missions in Washington, it is offered as a convenience to organizations and persons who must deal with consular representatives of foreign governments. It has been designed with particular attention to the requirements of government agencies, state tax officials, international trade organizations, chambers of commerce, and judicial authorities who have a continuing need for handy access to this type of information. Trade with other regions of the world has become an increasingly vital element in the economy of the United States. The machinery of this essential commerce is complicated by numerous restrictions, license requirements, quotas, and other measures adopted by the individual countries. Since the regulations affecting both trade and travel are the particular province of the consular service of the nations involved, reliable information as to entrance requirements, consignment of goods, details of transshipment, and, in many instances, suggestions as to consumer needs and preferences may be obtained at the foreign consular offices throughout the United States. -

Doma Vaquero My Journey in Understanding Spanish Traditions

Written by Alice Trindle Copyright: T&T Horsemanship May 2006 No portion of this article can be reproduced without the consent of the author Doma Vaquero My Journey in Understanding By Alice Trindle Spanish Traditions appreciate in the Quarter Horse were originally t all started with a horse! Juandero was a I placed in the gene pool by the Spanish beautiful bay Azteca gelding. He didn’t just Andalusian. The conquistadors brought the appear at my place…He arrived! His presence Spanish blood horses into Mexico during the was unmistakably alive, somewhat full of himself, Aztec era, and later on they brought them into but aware of everything around him and quite what became the continental United States with prepared to play. As I had the honor to begin to Spanish missionaries, and the Spanish army. work with Juandero I soon discovered there was These horses were very agile and athletic, as their more to this picture then a beautiful horse, with a heritage was to fight the bulls of Spain. Even willing and playful attitude, that carried himself in today, these bulls are not your average polled a natural balance that was light and suspended. Hereford with a docile temperament! The Spanish There was a tradition – a heritage – that was bull is bred for attitude with horns, and therefore exhibiting itself in every movement of this horse your horse must be able to leg-yield or half-pass, and I wanted to know more about it. canter and counter-canter, in balance and at various speeds. In Spain, the Doma Vaquero uses a 13-foot long wood pole called the garrocha for working the bulls, as well as a partner in an elegant dance and artistic display between horse, rider, and pole, set to beautiful Spanish guitar music. -

Chapter 6: End of Spanish Rule

End of Spanish Rule Why It Matters Europeans had ruled the New World for centuries. In the late 1700s people in the Americas began to throw off European rule. The thirteen English colonies were first. The French colony of Haiti was next. Texas was one part of the grand story of the independence of the Spanish colonies. For the people living in Texas, though, the transition from Spanish province to a territory in the independent nation of Mexico was tremendously important. The Impact Today • Texas was the region of North America in which Spanish, French, English, and Native Americans met. • Contact among people encourages new ways of thinking. Later the number of groups in Texas increased as African and Asian people, as well as others from all over the world, brought their cultures. 1773 1760 ★ Spanish 1779 ★ Atascosito Road used for abandon East • Nacogdoches military purposes Texas missions founded 1760 1770 1780 1790 1763 1773 1789 • Treaty of Paris ended • Captain James Cook crossed • George Washington Seven Years’ War the Antarctic Circle became first president 1783 1793 • Great Britain and United • Eli Whitney States signed peace treaty invented the cotton gin 136 CHAPTER 6 End of Spanish Rule Summarizing Study Foldable Make this foldable and use it as a journal to help you record key facts about the time when Spain ruled Texas. Step 1 Stack four sheets of paper, one on top of the other. On the top sheet of paper, trace a large circle. Step 2 With the papers still stacked, cut out all four circles at the same time. -

The Following Event Descriptions Are Presented for Your Edification and Clarification on What Is Being Represented and Celebrated in Bronze for Our Champions

The following event descriptions are presented for your edification and clarification on what is being represented and celebrated in bronze for our champions. RODEO: Saddle Bronc Riding Saddle Bronc has been a part of the Calgary Stampede since 1912. Style, grace and rhythm define rodeo’s “classic” event. Saddle Bronc riding is a true test of balance. It has been compared to competing on a balance beam, except the “apparatus” in rodeo is a bucking bronc. A saddle bronc rider uses a rein attached to the horse’s halter to help maintain his seat and balance. The length of rein a rider takes will vary on the bucking style of the horse he is riding – too short a rein and the cowboy can get pulled down over the horse’s head. Of a possible 100 points, half of the points are awarded to the cowboy for his ride and spurring action. The other half of the points come from how the bronc bucks and its athletic ability. The spurring motion begins with the cowboy’s feet over the points of the bronc’s shoulders and as the horse bucks, the rider draws his feet back to the “cantle’, or back of the saddle in an arc, then he snaps his feet back to the horse’s shoulders just before the animal’s front feet hit the ground again. Bareback Riding Bareback has also been a part of the Stampede since 1912. In this event, the cowboy holds onto a leather rigging with a snug custom fit handhold that is cinched with a single girth around the horse – during a particularly exciting bareback ride, a rider can feel as if he’s being pulled through a tornado. -

Shorty's Yarns: Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2004 Shorty's Yarns: Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon Bruce Kiskaddon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Kiskaddon, B., Field, K., & Siems, B. (2004). Shorty's yarns: Western stories and poems of Bruce Kiskaddon. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHORTY’S YARNS Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon Illustrations by Katherine Field Edited and with an introduction by Bill Siems Shorty’s Yarns THE LONG HORN SPEAKS The old long horn looked at the prize winning steer And grumbled, “What sort of a thing is this here? He ain’t got no laigs and his body is big, I sort of suspicion he’s crossed with a pig. Now, me! I can run, I can gore, I can kick, But that feller’s too clumsy for all them tricks. They’re breedin’ sech critters and callin’ ‘em Steers! Why the horns that he’s got ain’t as long as my ears. I cain’t figger what he’d have done in my day. They wouldn’t have stuffed me with grain and with hay; Nor have polished my horns and have fixed up my hoofs, And slept me on beddin’ in under the roofs Who’d have curried his hide and have fuzzed up his tail? Not none of them riders that drove the long trail. -

Spanish Relations with the Apache Nations East of the Rio Grande

SPANISH RELATIONS WITH THE APACHE NATIONS EAST OF THE RIO GRANDE Jeffrey D. Carlisle, B.S., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2001 APPROVED: Donald Chipman, Major Professor William Kamman, Committee Member Richard Lowe, Committee Member Marilyn Morris, Committee Member F. Todd Smith, Committee Member Andy Schoolmaster, Committee Member Richard Golden, Chair of the Department of History C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Carlisle, Jeffrey D., Spanish Relations with the Apache Nations East of the Río Grande. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May 2001, 391 pp., bibliography, 206 titles. This dissertation is a study of the Eastern Apache nations and their struggle to survive with their culture intact against numerous enemies intent on destroying them. It is a synthesis of published secondary and primary materials, supported with archival materials, primarily from the Béxar Archives. The Apaches living on the plains have suffered from a lack of a good comprehensive study, even though they played an important role in hindering Spanish expansion in the American Southwest. When the Spanish first encountered the Apaches they were living peacefully on the plains, although they occasionally raided nearby tribes. When the Spanish began settling in the Southwest they changed the dynamics of the region by introducing horses. The Apaches quickly adopted the animals into their culture and used them to dominate their neighbors. Apache power declined in the eighteenth century when their Caddoan enemies acquired guns from the French, and the powerful Comanches gained access to horses and began invading northern Apache territory. -

Trunk Contents

Trunk Contents Hands-on Items Bandana – Bandanas, also known as "snot rags," came in either silk or cotton, with the silk being preferred. Silk was cool in the summer and warm in the winter and was perfect to strain water from a creek or river stirred up by cattle. Cowboys favored bandanas that were colorful as well as practical. With all the dust from the cattle, especially if you rode in the rear of the herd (drag), a bandana was a necessity. Shirt - The drover always carried an extra shirt, as 3,000 head of cattle kicked up a considerable amount of dust. The drovers wanted a clean shirt available on the off- chance that the cowboy would be sent to a settlement (few and far between) to secure additional supplies. Crossing rivers would get your clothes wet and cowboys would need a clean and dry shirt to wear. Many times they just went into the river without shirt and pants. For superstitious reasons many cowboys did not favor red shirts. Cuffs - Cuffs protected the cowboy's wrist from rope burns and his shirt from becoming frayed on the ends. Many cuffs were highly decorated to reflect the individual's taste. Students may try on these cuffs. 1 Trunk Contents Long underwear – Cowboys sometimes called these one-piece suits "long handles." They wore long underwear in summer and winter and often kept them on while crossing a deep river, which gave them a measure of modesty. Long underwear also provided extra warmth. People usually wore white or red "Union Suits" in the West. -

Communication from Public

Communication from Public Name: Colleen Smith Date Submitted: 05/11/2021 11:21 AM Council File No: 20-1575 Comments for Public Posting: I would hope that banning certain devices used in rodeo would be the least of your concern. Given the absolutely abhorrent conditions that are currently plaguing your city and entire state, your efforts should be attempting to figure out your homeless problem!! Communication from Public Name: Date Submitted: 05/17/2021 01:38 PM Council File No: 20-1575 Comments for Public Posting: Please Do NOT Ban Rodeo and Bull Riding in Los Angeles! This ordinance is unnecessary – PBR already takes great care of the bulls!! - The health and safety of the animals in bull riding is paramount. These animal athletes get the best care and live a great life – extending four to five times as long as the average bull. - PBR stock contractors make their living by breeding, training, and working with their animal athletes. They truly love these animal athletes, treat them as a member of their own family, and have many safeguards in place to ensure their care. - The bulls in PBR are not wild animals forced to compete – they’re bred and trained for their jobs. Bulls buck because of their genetics. They are not abused or coerced to compete. The flank straps and dull spurs used in PBR do NOT harm the bulls. - In addition to bringing millions of dollars of economic impact to LA, bull riding teaches important values like hard work, charity, respect, responsibility, and honesty. The sport is inclusive and promotes equality. -

Ekphrasis and Avant-Garde Prose of 1920S Spain

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2015 Ekphrasis and Avant-Garde Prose of 1920s Spain Brian M. Cole University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cole, Brian M., "Ekphrasis and Avant-Garde Prose of 1920s Spain" (2015). Theses and Dissertations-- Hispanic Studies. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/23 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies.