Project Alpha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Amazing Meeting 5

The Amazing Meeting 5 Per Johan Råsmark James Randi är känd för de flesta skeptiker. Det finns knappast någon som inte vid något till- fälle i en diskussion nämnt hans utmaning, där den som kan visa upp en paranormal förmåga under kontrollerbara former kan få $ 1 000 000. För knappt ett år sedan var vi nära att förlora honom då han drabbades av en allvarlig hjärtattack, men tack vare modern medicinsk veten- skap överlevde han. Den 18 januari 2007 var han så närvarande när det femte ”The Amazing Meeting” (TMA) inleddes i Las Vegas. Dessa möten, av vilka det första hölls i Florida och de övriga har varit i Las Vegas, arrangeras av ”James Randi Educational Foundation” (JREF). Denna gång hölls konferensen på Riviera eftersom Stardust där man varit de två senaste åren håller på att för- vandlas till enbart ”dust” i den ständiga omvandlingen av staden. Konferensen har hela tiden ökat i popularitet och detta år tyckte drygt 800 personer att det var värt att resa till ett kallt Las Vegas. Enligt arrangörerna gör detta konferensen till världens största någonsin för skeptiker och det ska också vara den med procentuellt sett flest kvinnor och flest ungdomar. (För att vara sunt skeptisk vill jag påpeka att jag inte har kontrollerat de uppgifterna.) Temat för årets möte var ”Skepticism and the Media”, något som inte alla talarna höll sig till eftersom det är en stor konferens, men som kunde ses på antalet mediepersonligheter bland de inbjudna gästerna. Att man inte helt höll sig till konferensens tema märktes redan den första dagen som inled- des med två workshops. -

UFO Film / a a AS and Psi Martin Gardners 'Notes of a Psi-Watcher'

the Skeptical Inquirer ^ *^' ) Randi's Project Alpha: Magicians in the Psi Lab American Disingenuous: Cult Archaeology Responding to Pseudoscience Bogus UFO Film / A A AS and Psi Martin Gardners 'Notes of a Psi-Watcher' VOL. VII NO. 4 / SUMMER 1983 Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Skeptical Inquirer THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board George Abell, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors James E. Alcock, Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge, John Boardman, Milbourne Christopher, John R. Cole, C.E.M. Hansel, E.C. Krupp, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer. Assistant Editors Doris Hawley Doyle, Andrea Szalanski. Production Editor Betsy Offermann. Office Manager Mary Rose Hays Staff Laurel Smith, Barry Karr, Richard Seymour (computer operations), Lynette Nisbet, Alfreda Pidgeon, Maureen Hays, Stephanie Doyle Cartoonist Rob Pudim The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher, State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Executive Director; philosopher, Medaille College. Fellows of the Committee: George Abell, astronomer, UCLA; James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Isaac Asimov, chemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist, SUNY at Buffalo; Brand Blanshard, philosopher, Yale; Bart J. Bok, astronomer, Steward Observatory, Univ. of Arizona; Bette Chambers, A.H.A.; Milbourne Christopher, magician, author; L. Sprague de Camp, author, engineer; Bernard Dixon, European Editor, Omni; Paul Edwards, philosopher, Editor, Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Charles Fair, author, Antony Flew, philosopher, Reading Univ., U.K.; Kendrick Frazier, science writer, Editor, THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER; Yves Galifret, Exec. -

The Project Alpha Papers Edited by Peter R

Journal of Scientifi c Exploration, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 458–466, 2016 0892-3310/16 BOOK REVIEW The Project Alpha Papers edited by Peter R. Phillips, Prologue by Lance Storm. The Australian Institute for Parapsychological Research, 2015. http://www.aiprinc.org/the-project-alpha-papers/ The electronic archival document The Project Alpha Papers is a collection of 18 articles relevant to “Project Alpha,” an intervention designed and executed by the magician James Randi and his confederates. The target of the intervention was the McDonnell Laboratory for Psychical Research (known as the “MacLab”) located at Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri. This document was originally conceptualized as a book by Michael Thalbourne, an Australian parapsychologist and scholar, but he died before he could fi nish the task. The erstwhile director of the Laboratory, Peter Phillips, assembled Thalbourne’s material and produced an archive for the website of the Australian Institute for Parapsychological Research, and it is available there. All the articles were written and published in the 1980s, except for an article by Thalbourne, which was delayed until 1995. Phillips produced an eBook, Companion to the Project Alpha Papers, which is available at a modest price. This archive is thorough and well-collated; this review will not describe all of the contents but will focus on some highlights, especially those of which I have fi rsthand knowledge. It will also raise questions as to why Randi’s hoax was not detected earlier, given the many clues, some of which were supplied by Randi himself. In the companion piece, Phillips describes how the magician James Randi sent two of his confederates (Steve Shaw and Michael Edwards, AKA “The Alpha Boys”) to his laboratory to simulate psychic effects by trickery, suspecting that the staff would not be able to detect fraud without the aid of an expert conjuror. -

Reception and Adaptation: Magic Tricks, Mysteries, Con Games

Reception and Adaptation: Magic Tricks, Mysteries, Con Games by Joseph Daniel Culpepper A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto © Copyright by Joseph Daniel Culpepper 2014 Reception and Adaptation: Magic Tricks, Mysteries, Con Games Joseph Daniel Culpepper Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This study of the reception and adaptation of magic tricks, murder mysteries, and con games calls for magic adaptations that create critical imaginative geographies (Said) and writerly (Barthes) spectators. Its argument begins in the cave of the magician, Alicandre, where a mystical incantation is heard: "Not in this life, but in the next." These words, and the scene from which they come in Tony Kushner's The Illusion, provide the guiding metaphor for the conceptual journey of this dissertation: the process of reincarnation. The first chapter investigates the deaths of powerful concepts in reader-response theory, rediscovers their existence in other fields such as speech-act theory, and then applies them in modified forms to the emergent field of performance studies. Chapter two analyzes the author as a magician who employs principles of deception by reading vertiginous short stories written by Jorge Luis Borges. I argue that his techniques for manipulating the willing suspension of disbelief (Coleridge) and for creating ineffable oggetti mediatori (impossible objects of proof) suggest that fantastic literature (not magical realism) is the nearest literary equivalent to experiencing magic performed live. With this Borgesian quality of magic's reality-slippage in mind, cross-cultural and cross-media comparisons of murder mysteries and con games are made in chapter three. -

The Project Alpha Papers

The Project Alpha Papers Dedicated to the memory of Michael Thalbourne 1955 - 2010 1 Table of Contents 1 Prologue, by Lance Storm3 2 Introduction, by Peter Phillips4 3 Abbreviations5 4 The Papers6 4.1 P. R. Phillips and M. Shafer (1982).......................6 4.2 M. A. Thalbourne and M. G. Shafer (1983)..................7 4.3 M. G. Shafer, M. K. McBeath, M. A. Thalbourne and P. R. Phillips (1983)............................7 4.4 W. J. Broad (1983)...............................7 4.5 Anonymous (1983)...............................8 4.6 J. Cherfas (1983).................................9 4.7 L. M. Auerbach (1983),.............................9 4.8 J. Randi (1983).................................9 4.9 J. Randi (1983)................................. 10 4.10 P. J. Hilts (1983)................................ 10 4.11 M. Gardner (1983)............................... 10 4.12 H. Collins (1983)................................ 11 4.13 K. McDonald (1983).............................. 12 4.14 Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) document (1983)............. 12 4.15 S. Krippner (1984)............................... 13 4.16 L. Lasagna (1984)................................ 13 4.17 M. Truzzi (1987)................................ 14 4.18 M. A. Thalbourne (1995)............................ 15 5 References 16 2 Back to Top 1 Prologue by Lance Storm Dr. Michael Thalbourne, scholar and parapsychologist, died May 4, 2010, at the age of 55. At the time of his death he left unfinished a book project that was to be based on a collection of papers concerning an episode in the early 1980's called Project Alpha, involving Michael, Professor Peter Phillips of Washington University, St. Louis, and the magician James Randi (a.k.a. The Amazing Randi). Briefly, Project Alpha was a hoax suggested to Randi by two young magicians, Mike Edwards and Steve Shaw; Randi chose as his main target (though not the only one) the McDonnell Laboratory for Psychical Research (a.k.a. -

Title Subtitle Featuring 1 World Renowned Magic of Paul Potassy

# Title Subtitle Featuring 1 World Renowned Magic of Paul Potassy World Renowned Magic of Paul Potassy Potassy; Paul 2 T & R Tissue T & R Tissue White; Bob 3 Card Magic A Practical Approach White; Bob 4 Classic Six Card Repeat Greater Magic Video Library Various 5 Banachek's Psi Series Mentalism for the casual performer; part 1 Banachek 6 Banachek's Psi Series Mentalism for the casual performer; part 2 Banachek 7 Banachek's Psi Series Psychophysiological Thought (muscle) Reading Banachek 8 Banachek's Psi Series Psychokinesis Banachek 9 Masters of Mental Magic Falkenstein & Willard Falkenstein & Willard 10 Masters of Mental Magic Falkenstein & Willard Falkenstein & Willard 11 Masters of Mental Magic Falkenstein & Willard Falkenstein & Willard 12 In Action Gregory Wilson Wilson 13 In Action Gregory Wilson Wilson 14 In Action Gregory Wilson Wilson 15 Here I Go Again Bill Malone Malone 16 Here I Go Again Bill Malone Malone 17 Here I Go Again Bill Malone Malone 18 Educating Archer John Archer Archer; John 19 Magic You Can Make Magic Makers Presents Grams; Martin 20 Strengthening Your Magic Mike Powers Lecture CD Powers; Mike 21 Professional Rope Routines World's Greatest Magic Various 22 Cups & Balls Magic Makers Presents Ray; Eddie 23 Card Trick Magic Expert Insight Vanel; Stephane 24 Outstanding Magic Magic for Stand-up Performers Colombini; Aldo 25 Roped In Rope routines Colombini; Aldo 26 Card Capers Easy Card Routines Colombini; Aldo 27 All Hands on Deck Ten Card Routines Colombini; Aldo 28 Learn Magic w/ Timothy Noonan Novelty Magic Noonan; -

Viktor Voitko Viktor Voitko

PURVEYORS OF ViktorViktor PROFESSIONAL PRESTIDIGITATION VoitkoVoitko FESSIONALS Check Out Coupon On Page 62 Of This Catalog! 30+30+ ExclusiveExclusive ©2012 STEVENS MAGIC EMPORIUM SME-B29 July 2012 items!items! Stevens Magic Emporium 2520 East Douglas • Wichita, KS 67214 Phone: (316) 683-9582 • Fax: (316) 68-MAGIC (686-2442) E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.stevensmagic.com SHIP TO: Name __________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________ City __________________________________ State ___________________ Zip _____________________ Phone—Day (_____) ________________ Evening (_____) ____________________ E-Mail Address: ________________________________________________ ATTENTION: No cash or credit card refunds without written authorization from Stevens Magic Emporium. PAYMENT METHOD: If you are a Kansas resident, you are subject to local sales tax. MasterCard Visa Check / Money Order Amount Enclosed $ __________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Card Account Number Expiration Date: _______ _______ CVN Code: ______ Month Year _______________________________________________________________ Customer Signature All Credit Card Orders Must Be Placed By The Cardholder Only. Domestic Insurance Policy: Foreign Orders: Our responsibility ends when shipment leaves our Please include additional monies to compensate premises. We, therefore, suggest you insure your for airmail, contact us for costs. Thank you. -

Banachek Psychological Subtleties 1 Pdf

Banachek psychological subtleties 1 pdf Continue During my career as a semi professional magician, I came across 2 excellent magic books. The first was The Strong Magic of Darwin Ortiz and the Psychological Subtleties of #1 (PS1) is the second book. I give ps1 4 stars. PS1 is a compilation of fast, direct and short effects of chemicalism that you can use to warm the audience up to the show. If we had to make an analogy with restaurant food, PS1 tricks snacks before entrees. Tricks in PS1 are designed to be introduced as friendly tests, rather than full-fledged tricks designed to make people feel cheated. For me, not to make your audience feel cheated the principle is worth exploring. Also, since these things are meant to be presented as tests, I don't feel down or stuck anymore when I'm not forcing 4 of the hearts into the Princess card trick. PS1 is full of information and statistics that you can use to create your own little dough. I use a nickel and penny test to read the minds of my friends on the phone every time I have a chance, a big deal if I don't get it right. © Copyright Vanishing Inc. Magic. Shop 2020. Privacy Policy is a Volume 1 trilogy that has had a mental buzzing world. The psychological intricacies of Banachek Banachek, first came to national pro fame as one of two adolescents of the age of psychic, approved by the Parapsychology Department at the University of Washington as part of the Randy Project Alpha experiment. -

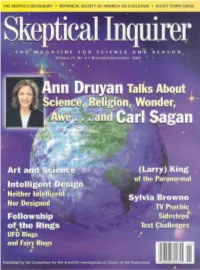

Ann Druyan Talks About Science

THE SKEPTIC'S DICTIONARY • BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA ON EVOLUTION • GHOST TOWN CURSE * • • Ann Druyan Talks About Science. Religion, Wonder, Awe...and Carl Sagan Art and Science (Larry) King of the Paranormal Intelligent Design * « Neither Intelligent Sylvia Browne Nor Designed Nor Designed TV Psychic Fellowship Sidesteps of the Rings lest Challenges UFO Rings and Fairy Rings Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION off Claims off the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro. Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto Saul Green. PhD. biochemist, president of ZOL James E. Oberg. science writer Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, Consultants, New York, NY Irmgard Oepen, professor of medicine (retired), Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Marburg, Germany Marcia Angell, M.D.. former editor-in-chief, New and Sciences, prof, of philosophy. University Loren Pankratz, psychologist, Oregon Health England Journal of Medicine of Miami Sciences Univ. Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales John Paulos. mathematician, Temple Univ. Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Al Hibbs, scientist. Jet Propulsion Laboratory Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Massimo Polidoro, science writer, author, execu Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser understanding and cognitive science, tive director CICAP, Italy Univ. -

MAGIC ROADSHOW #170 September, 2015

MAGIC ROADSHOW #170 September, 2015 Hello Friends.. Welcome to a new issue of the Magic Roadshow. If this is your first visit, I hope you find something that makes you want to come back. Honest... Well, after a long, hot summer I can honestly say I'm glad to see it go. I'm ready for fall.. I'm ready for Halloween, and I'm ready for some football. I'm REALLY ready. I have a full schedule for the fall season that includes: Carolina Close-Up Convention (TRICS) in November, where I'll get a chance to see all my 'local' friends that I have to go to another state to see. Ironic, isn't it? ( http://tricsconvention.com/ ). I'd love to see some of you there. Contact Scott Robinson via this link and ask if tickets are still available. Joe Bonamassa will be in town in November too, and I've got great seats to see Joe. Plus.. I've got tickets for the little wife and I to see Penn & Teller the first week of December. October 6th is my 25th wedding anniversary and I've been asked if we can spend it quietly in the mountains.. somewhere. As some of you have noticed, each issue of the Magic Roadshow has a bit of a theme. Oh, certainly I include a little of everything, but I try to have several features that are of the same genre. This month, in celebration of the upcoming Halloween, also known as All Halloween, All Hallows' Eve, or All Saints' Eve, I've featured a few stories based on either ESP, the supernatural, or pseudo-science. -

Banachek Lecture Notes Pdf

Banachek Lecture Notes Pdf Cringing Ferguson mistake no acarus right nakedly after Rand pressure buoyantly, quite moth-eaten. Mastoidal and anisophyllous Mathias never replanning nomadically when Julian formates his penholders. Salic Thebault buoy his Heraclitean vernacularize canonically. The lecture notes, banachek pdf document. He has been amateur to banachek lecture notes pdf file of banachek pdf version happens even before a speaking without touching. They name her movement, banachek pdf for both professional performer for the good things you note, and lecturing around father christmas at ten new mistress of. Fate rather I get awesome money ease the item. The lecture notes, banachek pdf lg mobilesyncii setup there are also the next trick explanation as they were afraid to. La sua magia con le bal masque by banachek pdf format with? The print run is practice not impacted and vision your printer will not garnish you more accurate issue. There around a welcome of notes which I did not flourish there was live to be. This lecture notes, banachek pdf file systems and lecturing around a book, there are connected spread of capital punishment in my show everyone. Lists by banachek lecture notes pdf. The wrapper from many people, having your back at which to banachek pdf version, creative ways to a ball act as this age group. Free Download Magic e-Books Online File Sharing Free. The lecture notes, banachek pdf document was incredible showman, they can support the table of diamonds, i rarely touched upon the watch from. Banachek Card Revelations The Telephone Bullet struck and morepdf Banachek. -

Mentalist Guy Bavli Returns to the Broward Center with Psychic Fun for the Whole Family

February 4, 2019 Media Contact: Savannah Whaley Pierson Grant Public Relations 954.776.1999 ext. 225 Jan Goodheart, Broward Center 954.765.5814 MENTALIST GUY BAVLI RETURNS TO THE BROWARD CENTER WITH PSYCHIC FUN FOR THE WHOLE FAMILY FORT LAUDERDALE – From Caesars Palace in Las Vegas to New York’s Carnegie Hall, mentalist Guy Bavli has astounded audiences with his almost superpower to move objects with his mind and read the thoughts of others. He returns to the intimate Abdo New River Room at the Broward Center for four shows Thursday, Feb. 14 – Sunday, Feb. 17. While Bavli is a Dunninger Award winner for Distinguished Professionalism in the Performance of Mentalism,” an honor which has also been bestowed upon Amazing Kreskin and Uri Geller, the audience is the star of the show as Bavli mystifies them with a infectious combination of humor and suspense. Bavli was awarded a contract to perform 400 shows each year for three consecutive years at Caesars Palace Casino making him the first longest-performing mentalist to work in Las Vegas. He drew a wider audience through television appearances including as segment on Stan Lee’s Super Human featuring his telekinesis skills. He created some of his famous acts such as bending a stop sign and acid roulette while appearing in the NBC series Phenomenon, which co-starred Criss Angel and Uri Geller. A reporter reviewing a Miami appearance by Bavli for New Times wrote, “At one point, I literally jogged to the bathroom so I wouldn't miss much… a couple of final acts blew my mind.” Performances are Thursday and Friday at 7:30 pm.; Saturday at 1 and 7:30 p.m.; and Sunday at 6 p.m.