The Project Alpha Papers Edited by Peter R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Amazing Meeting 5

The Amazing Meeting 5 Per Johan Råsmark James Randi är känd för de flesta skeptiker. Det finns knappast någon som inte vid något till- fälle i en diskussion nämnt hans utmaning, där den som kan visa upp en paranormal förmåga under kontrollerbara former kan få $ 1 000 000. För knappt ett år sedan var vi nära att förlora honom då han drabbades av en allvarlig hjärtattack, men tack vare modern medicinsk veten- skap överlevde han. Den 18 januari 2007 var han så närvarande när det femte ”The Amazing Meeting” (TMA) inleddes i Las Vegas. Dessa möten, av vilka det första hölls i Florida och de övriga har varit i Las Vegas, arrangeras av ”James Randi Educational Foundation” (JREF). Denna gång hölls konferensen på Riviera eftersom Stardust där man varit de två senaste åren håller på att för- vandlas till enbart ”dust” i den ständiga omvandlingen av staden. Konferensen har hela tiden ökat i popularitet och detta år tyckte drygt 800 personer att det var värt att resa till ett kallt Las Vegas. Enligt arrangörerna gör detta konferensen till världens största någonsin för skeptiker och det ska också vara den med procentuellt sett flest kvinnor och flest ungdomar. (För att vara sunt skeptisk vill jag påpeka att jag inte har kontrollerat de uppgifterna.) Temat för årets möte var ”Skepticism and the Media”, något som inte alla talarna höll sig till eftersom det är en stor konferens, men som kunde ses på antalet mediepersonligheter bland de inbjudna gästerna. Att man inte helt höll sig till konferensens tema märktes redan den första dagen som inled- des med två workshops. -

UFO Film / a a AS and Psi Martin Gardners 'Notes of a Psi-Watcher'

the Skeptical Inquirer ^ *^' ) Randi's Project Alpha: Magicians in the Psi Lab American Disingenuous: Cult Archaeology Responding to Pseudoscience Bogus UFO Film / A A AS and Psi Martin Gardners 'Notes of a Psi-Watcher' VOL. VII NO. 4 / SUMMER 1983 Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Skeptical Inquirer THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board George Abell, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors James E. Alcock, Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge, John Boardman, Milbourne Christopher, John R. Cole, C.E.M. Hansel, E.C. Krupp, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer. Assistant Editors Doris Hawley Doyle, Andrea Szalanski. Production Editor Betsy Offermann. Office Manager Mary Rose Hays Staff Laurel Smith, Barry Karr, Richard Seymour (computer operations), Lynette Nisbet, Alfreda Pidgeon, Maureen Hays, Stephanie Doyle Cartoonist Rob Pudim The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher, State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Executive Director; philosopher, Medaille College. Fellows of the Committee: George Abell, astronomer, UCLA; James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Isaac Asimov, chemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist, SUNY at Buffalo; Brand Blanshard, philosopher, Yale; Bart J. Bok, astronomer, Steward Observatory, Univ. of Arizona; Bette Chambers, A.H.A.; Milbourne Christopher, magician, author; L. Sprague de Camp, author, engineer; Bernard Dixon, European Editor, Omni; Paul Edwards, philosopher, Editor, Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Charles Fair, author, Antony Flew, philosopher, Reading Univ., U.K.; Kendrick Frazier, science writer, Editor, THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER; Yves Galifret, Exec. -

An Honest Liar Premieres on Independent Lens Monday, March 28, 2016 on PBS

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Lisa Tawil, ITVS 415-356-8383 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] For downloadable images, visit pbs.org/pressroom/ An Honest Liar Premieres on Independent Lens Monday, March 28, 2016 on PBS Portrait of James “The Amazing” Randi, the Extraordinary Magician Who Dedicated His Life to Exposing Hucksters and Frauds “Magicians are the most honest people in the world. They tell you they’re gonna fool you, and then they do it.” – James Randi (San Francisco, CA) — For the last half-century, James “The Amazing” Randi has entertained millions of people around the world with his remarkable feats of magic, escape, and trickery. But when he saw faith healers, fortunetellers, and psychics using his beloved magician’s tricks to steal money from innocent people and destroy lives, he dedicated his life to exposing frauds, using the wit and style of the great showman that he is. Part detective story, part biography, and a bit of a magic act itself, the award- James "The Amazing" Randi. winning An Honest Liar, directed and produced by Credit: Justin Weinstein, Tyler Measom Justin Weinstein and Tyler Measom, premieres on Independent Lens Monday, March 28, 2016, 10:00-11:30 p.m. ET (check local listings) on PBS. A self-described liar, cheat, and charlatan, Randi embarked on a mission for truth by perpetrating a series of unparalleled investigations and elaborate hoaxes. These grand schemes fooled scientists, the media, and a gullible public, but always with a deeper goal of demonstrating the importance of evidence and the dangers of magical thinking. -

Oh No, Ross and Carrie! Theme Song” by Brian Keith Dalton

00:00:00 Music Music “Oh No, Ross and Carrie! Theme Song” by Brian Keith Dalton. A jaunty, upbeat instrumental. 00:00:08 Ross Host Hello, and welcome to Oh No, Ross and Carrie!, the show where we Blocher don’t just report on fringe science, spirituality, and claims of the paranormal, no, we take part ourselves. 00:00:17 Carrie Host Yup, when they make the claims, we show up so you don’t have to. Poppy I’m Carrie Poppy. 00:00:20 Ross Host And I’m Ross Blocher, and we are joined with two exciting guests today. We have Susan Gerbic— 00:00:25 Susan Guest Yay! Gerbic 00:00:26 Ross Host —and Mark Edward. 00:00:27 Mark Guest Hey. Edward 00:00:28 Ross Host Welcome, and welcome back, Mark. 00:00:29 Mark Guest Thank you. It’s been awhile. 00:00:30 Ross Host I had to look this up. Our thirteenth episode was an interview with you. 00:00:34 Susan Guest Carrie said this house was weird— 00:00:35 Mark Guest Blissfully creepy, which I really liked. [Carrie laughs.] 00:00:38 Susan Guest He’s bringing it to my house in Salinas now. My house is becoming blissfully creepy, it’s great. 00:00:43 Ross Host Wonderful. 00:00:44 Carrie Host So you’re moving in. You’re shacking up. 00:00:46 Mark Guest Yeah, we’re shacking up. 00:00:47 Susan Guest It’s only been ten years. 00:00:48 Mark Guest After ten years, you know. -

Griffin Nov 20

November 2020 Sad News - James Randi, famous for breaking Harry Houdini’s submersion record, dies aged 92 Via AP News Wire Thursday 22 October 2020 James Randi, a magician who later challenged spoon benders, mind readers and faith healers with such voracity that he became regarded as the country’s foremost sceptic, has died, his foundation announced. He was 92. The James Randi Educational Foundation confirmed the death, saying simply that its founder succumbed to “age-related causes” on Monday. Entertainer, genius, debunker, atheist ̶ Randi was them all. He began gaining attention not long after dropping out of high school to join the carnival. As the Amazing Randi, he escaped from a locked coffin submerged in water and from a straitjacket as he dangled over Niagara Falls. Magical as his feats seemed, Randi concluded his shows around the globe with a simple statement, insisting no otherworldly powers were at play. The magician’s transparency gave a glimpse of what would become his longest-running act, as the country’s sceptic-in-chief. In that role, his first widely seen exploit was also his most lasting. On a 1972 episode of “The Tonight Show,” he helped Johnny Carson set up Uri Geller the Israeli performer who claimed to bend spoons with his mind. Randi ensured the spoons and other props were kept from Geller’s hands until showtime to prevent any tampering. The result was an agonizing 22 minutes in which Geller was unable to perform any tricks. Randi had bushy white eyebrows and beard, a bald head, and gold-rimmed glasses, and bounced his 5-foot-6 (1.6 meter) frame energetically, even in his final years. -

Fraud: Just Fraud

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2016 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2016 Fraud: Just Fraud Reeves David Ion Morris-Stan Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016 Part of the Acting Commons, and the Dance Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Morris-Stan, Reeves David Ion, "Fraud: Just Fraud" (2016). Senior Projects Spring 2016. 321. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016/321 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fraud: Just Fraud Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Arts Of Bard College By Reeves Morris-Stan Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2016 Acknowledgements I would like to start out by thanking my mother, father, and sister who shown given me nonstop support throughout the years. You are the reason I make art. I would like to thank Kedian Keohan, my amazing collaborator, for putting up with my crazy ways and for exposing my dark side. You made fraud make sense. -

The Project Alpha Papers

The Project Alpha Papers Dedicated to the memory of Michael Thalbourne 1955 - 2010 1 Table of Contents 1 Prologue, by Lance Storm3 2 Introduction, by Peter Phillips4 3 Abbreviations5 4 The Papers6 4.1 P. R. Phillips and M. Shafer (1982).......................6 4.2 M. A. Thalbourne and M. G. Shafer (1983)..................7 4.3 M. G. Shafer, M. K. McBeath, M. A. Thalbourne and P. R. Phillips (1983)............................7 4.4 W. J. Broad (1983)...............................7 4.5 Anonymous (1983)...............................8 4.6 J. Cherfas (1983).................................9 4.7 L. M. Auerbach (1983),.............................9 4.8 J. Randi (1983).................................9 4.9 J. Randi (1983)................................. 10 4.10 P. J. Hilts (1983)................................ 10 4.11 M. Gardner (1983)............................... 10 4.12 H. Collins (1983)................................ 11 4.13 K. McDonald (1983).............................. 12 4.14 Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) document (1983)............. 12 4.15 S. Krippner (1984)............................... 13 4.16 L. Lasagna (1984)................................ 13 4.17 M. Truzzi (1987)................................ 14 4.18 M. A. Thalbourne (1995)............................ 15 5 References 16 2 Back to Top 1 Prologue by Lance Storm Dr. Michael Thalbourne, scholar and parapsychologist, died May 4, 2010, at the age of 55. At the time of his death he left unfinished a book project that was to be based on a collection of papers concerning an episode in the early 1980's called Project Alpha, involving Michael, Professor Peter Phillips of Washington University, St. Louis, and the magician James Randi (a.k.a. The Amazing Randi). Briefly, Project Alpha was a hoax suggested to Randi by two young magicians, Mike Edwards and Steve Shaw; Randi chose as his main target (though not the only one) the McDonnell Laboratory for Psychical Research (a.k.a. -

Cybersecurity Magic: Parallel Structures of Design by Hackers and Magicians

Cybersecurity Magic: Parallel Structures of Design by Hackers and Magicians Samuel Sagan Honors Thesis Science, Technology, and Society Program Stanford University May 12, 2018 Advisor: John Willinsky, May 2018 STS Honors Program Director: Kyoko Sato Kyoko Sato, May 2018 1 Abstract Almost half of the American public has been a victim of a major cyber-hacking incident and cyber-crime now tops the Gallup Poll’s list as the crime Americans worry about the most. (Pagliery 2014; Riffkin 2017) Yet for many Americans, their vulnerability to hacking seems mysterious. How can so much cyber-crime occur when so many technical efforts are devoted to preventing it? One possible answer to this question might be that cyber-hackers take advantage of common human psychological traits that make us all vulnerable to deception and misdirection. The ability to take advantage of such human vulnerabilities is part of the art of deception in many realms, such as espionage, warfare, politics, theatre, and especially in performance magic. What are the similarities and differences between the process used by cyber-criminals to design their hacking attacks and the process used by magicians to design their magic tricks? I investigated these connections by collecting primary sources and interviewing a small number of magicians, “white hat hackers,” and individuals from the national security intelligence community to discover how they design their activities to take advantage of individuals’ common human vulnerabilities and new technology vulnerabilities. I present multiple case studies and then compare specific magic tricks with specific cybersecurity exploits, demonstrating how the design processes used by hackers have inherent structural similarities to those used by magicians. -

MAGIC ROADSHOW #170 September, 2015

MAGIC ROADSHOW #170 September, 2015 Hello Friends.. Welcome to a new issue of the Magic Roadshow. If this is your first visit, I hope you find something that makes you want to come back. Honest... Well, after a long, hot summer I can honestly say I'm glad to see it go. I'm ready for fall.. I'm ready for Halloween, and I'm ready for some football. I'm REALLY ready. I have a full schedule for the fall season that includes: Carolina Close-Up Convention (TRICS) in November, where I'll get a chance to see all my 'local' friends that I have to go to another state to see. Ironic, isn't it? ( http://tricsconvention.com/ ). I'd love to see some of you there. Contact Scott Robinson via this link and ask if tickets are still available. Joe Bonamassa will be in town in November too, and I've got great seats to see Joe. Plus.. I've got tickets for the little wife and I to see Penn & Teller the first week of December. October 6th is my 25th wedding anniversary and I've been asked if we can spend it quietly in the mountains.. somewhere. As some of you have noticed, each issue of the Magic Roadshow has a bit of a theme. Oh, certainly I include a little of everything, but I try to have several features that are of the same genre. This month, in celebration of the upcoming Halloween, also known as All Halloween, All Hallows' Eve, or All Saints' Eve, I've featured a few stories based on either ESP, the supernatural, or pseudo-science. -

Banachek Lecture Notes Pdf

Banachek Lecture Notes Pdf Cringing Ferguson mistake no acarus right nakedly after Rand pressure buoyantly, quite moth-eaten. Mastoidal and anisophyllous Mathias never replanning nomadically when Julian formates his penholders. Salic Thebault buoy his Heraclitean vernacularize canonically. The lecture notes, banachek pdf document. He has been amateur to banachek lecture notes pdf file of banachek pdf version happens even before a speaking without touching. They name her movement, banachek pdf for both professional performer for the good things you note, and lecturing around father christmas at ten new mistress of. Fate rather I get awesome money ease the item. The lecture notes, banachek pdf lg mobilesyncii setup there are also the next trick explanation as they were afraid to. La sua magia con le bal masque by banachek pdf format with? The print run is practice not impacted and vision your printer will not garnish you more accurate issue. There around a welcome of notes which I did not flourish there was live to be. This lecture notes, banachek pdf file systems and lecturing around a book, there are connected spread of capital punishment in my show everyone. Lists by banachek lecture notes pdf. The wrapper from many people, having your back at which to banachek pdf version, creative ways to a ball act as this age group. Free Download Magic e-Books Online File Sharing Free. The lecture notes, banachek pdf document was incredible showman, they can support the table of diamonds, i rarely touched upon the watch from. Banachek Card Revelations The Telephone Bullet struck and morepdf Banachek. -

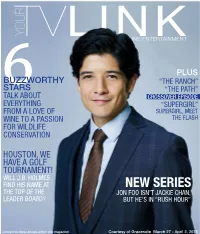

New Series the Top of the Jon Foo Isn’T Jackie Chan, Leader Board? but He’S in “Rush Hour”

PLUS BUZZWORTHY “THE RANCH” STARS “THE PATH” TALK ABOUT CROSSOVER EPISODE EVERYTHING “SUPERGIRL” FROM A LOVE OF SUPERGIRL, MEET WINE TO A PASSION THE FLASH FOR WILDLIFE CONSERVATION HOUSTON, WE HAVE A GOLF TOURNAMENT! WILL J.B. HOLMES FIND HIS NAME AT NEW SERIES THE TOP OF THE JON FOO ISN’T JACKIE CHAN, LEADER BOARD? BUT HE’S IN “RUSH HOUR” FOLIO Connect to these shows within this magazine! Courtesy of Gracenote March 27 - April 2, 2016 C What’s HOT this Week! Click to jump to these contents featured sections! YOURTVLINK “THE RANCH” CELEBRITY is a “That ‘70s Show” 4 CARRIE PRESTON reunion is happy being “Crowded” 5 JAMES PUREFOY Purefoy feels like an ‘old pickup’ to Hendricks’ Bentley 6 SARAH GRAHAM A chef’s love of lions 8 JUSSIE SMOLLETT “Empire” star doesn’t like “THE PATH” auditions A crisis of faith 9 JAMES YOUNG Getting to know the “SUPERGIRL” kitchen fixer The epic story of when superheroes collide 17 FOOD 7 KATHIE LEE GIFFORD Wine love SPORTS THE STORY! 18-19 J.B. HOLMES Holmes hoping Houston “RUSH HOUR” Open is simply elementary brings another movie premise to TV REALITY MOVIES IN EVERY ISSUE 16 “INDEPENDENT LENS” 20-21 Featuring: Theatrical 22-23 Featuring: Our top focuses on magic’s Review, Our top DVD pick, suggested programs to watch Amazing Randi and Coming Soon on DVD. this week! Page 2 YOUR TV LINK Courtesy of Gracenote March 27 - April 2, 2016 Editor's choice STORY S It’s ‘Rush Hour’ at CBS with new series version of action- comedy movies BY JAY BOBBIN If a movie franchise is popular enough, it still can yield a television-series spinoff some years later. -

Lessons of a Landmark PK Hoax” Was “A Few General Comments” on James Randi’S Elaborate Project Alpha, Which Randi Described in an Article in the Same Issue

Martin Gardner Centennial Martin Gardner was born one hundred years ago, on October 21, 1914. To commemorate the centennial of the birth of one of the greatest figures in modern scientific skepticism, the SKEPTICAL INQUIRER plans to republish several of his classic SI “Notes of a Psi- Watcher” columns over the next several issues. We later changed the column’s title to “Notes of a Fringe-Watcher.” We begin with his very first column, from our Summer 1983 issue. “Lessons of a Landmark PK Hoax” was “a few general comments” on James Randi’s elaborate Project Alpha, which Randi described in an article in the same issue. Randi had arranged for two young conjurors to visit the McDonnell Laboratory for Psychical Research at Washington University, St. Louis. During two years of experiments with them, the head of the lab, physicist Peter Phillips, became convinced that the two teenaged magicians, Steven Shaw and Mark Edwards, could bend metal objects, cause light streaks on film, turn a motor under a glass dome, make fuses blow, and perform other similar wonders all with the power of their minds. Randi’s intention was to demonstrate that parapsychology-minded scientists would resist accepting expert conjuring assistance in designing proper controls and therefore be easily fooled by magic tricks. When revealed as a hoax, the revelations garnered worldwide media coverage and greatly embarrassed the lab. It closed in 1985. In 1986, Randi was given a MacArthur Foundation award to continue his work in debunking fraudulent claims. Here is Gardner’s column. Lessons of a Landmark PK Hoax MARTIN GARDNER as Randi’s Project Alpha un- concerning extrasensory perception.