How to Turn Heads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hat Magazine Archive Issues 1 - 10

The Hat Magazine Archive Issues 1 - 10 Issue No Date Main Articles Workroom Process ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 1 Apr-Jun 1999 Luton - Ascot Shoot - Sean Barratt Feathers - Dawn Bassam -Trade Shows - Fashion Museums & Dillon Wallwork ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 2 Jul-Sep 1999 Paris – Marie O’Regan – Royal Ascot Working with crinn with - Student Shows – Geoff Roberts Frederick Fox ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 3 Oct-Nov 1999 Hat Designer of the Year ’99 - Block Making with Men in Hats, shoot – Trade Fairs Serafina Grafton-Beaves ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 4 Jan-Mar 2000 Mitzi Lorenz – Philip Treacy couture Working with sinamay (1) show Paris – Florence – Bridal shoot with Marie O’Regan Street page – Trades Shows ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 5 Apr-Jun 2000 Coco Chanel – Trade Fairs Working with sinamay (2) Dagmara Childs – Knits Shoot with Marie O’Regan Street page - Trade Shows ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 6 Jul-Sep 2000 Luton shoot – Royal Ascot Working with -

Retail Product Merchandising: Retail Buying-Selling Cycle

Retail Product Merchandising: Retail Buying-Selling Cycle SECTION 2: Establishing the Retail Merchandise Mix Part 1: The Basics of the Retail Merchandise Mix Part 1: 1-2 Industry Zones in the Apparel Industry Fashion products, especially in the women’s wear industry, are categorized by the industry zone in which they are produced and marketed. Industry has designated these zones as a) Haute Couture or couture, b) designer, c) bridge, d) contemporary, e) better, f) moderate, g) popular price/budget/mass, and g) discount/off price. Often the industry emphasizes the wholesale costs or price points of the merchandise in order to define the zone. However, price alone is not the major factor impacting the placement of the merchandise in the zone. Major factors impacting the zone classifications include the following criteria: . fashion level of the design (i.e., degree of design innovation inherent or intrinsic to the merchandise) . type and name of designer creating and developing the design concept . wholesale cost and retail price of product . types and quality of fibers and fineness of fabrications, trims, and findings . standards of construction quality or workmanship quality. In summary, the classification of a zone is based on the type of designer creating the product, design level of the product, type and quality of fabrications, standards of the workmanship, and the price range of the merchandise. Therefore, depending upon the lifestyle of the target consumer, the fashion taste level of that consumer (i.e., position of product on the fashion curve), and the current fashion trend direction in the market, the retailer, when procuring the merchandise mix, selects the industry zone(s) which offer(s) the product characteristics most desired by the target consumer. -

The Mini Skirt Danielle Hueston New York City College of Technology Textiles

The Mini Skirt Danielle Hueston New York City College of Technology Textiles When I was six my mother and I took one of our weekly day shopping trips to the mall. On our way back we stopped at this local thrift store. This being one of the first times I had ever experienced one, everything seemed so different and weird, in a good way. I wasn’t used to there only being one of everything, or one store that sold clothes, books, toys, home decor and shoes.Walking down the ‘bottoms aisle’ is where I first came across it. It was black and flowy, probably a cotton material, with a black elastic band around the waist. I wanted it, I needed it. It was the perfect mini skirt. It reminded me of the one I saw Regina George wear in the Hallway Scene in the movie ‘Mean Girls’ a few months prior and had to get it, even though it was a “little” big. There was only one, I was going to make it work. When Monday came I wasted no time showing off my new skirt at school. It made me feel like a whole new person. At some point of the day however my teacher had stepped out of the room to talk to another teacher, in conjunction one of my classmates playfully grabbed my pencil out of my hand, to which I decided to chase him around the room to retrieve it back. I tripped and my skirt fell right to my ankles, in front of the entire class. -

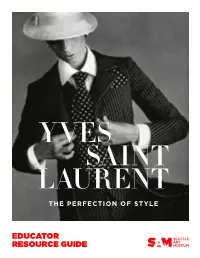

Yves Saint Laurent: the Perfection of Style: Educator Resource Guide

EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE OVERVIEW ABOUT THE EXHIBITION Organized by the Seattle Art Museum in partnership with the Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent, Yves Saint Laurent: The Perfection of Style highlights the legendary fashion designer’s 44-year career. Known for his haute couture designs, Yves Saint Laurent’s creative process included directing a team of designers working to create his vision of each garment. He would often begin by sketching the clothing he imagined, then a team would work to sew and create his designs. After the first version of the garment was created with simple fabric called muslin, Saint Laurent would select the final fabric for the garment. Under Saint Laurent’s direction, his team would piece the garment together—first on amannequin , next on a model. Working collaboratively, the team made changes according to Saint Laurent’s decisions, sewing new parts before the final garment was finished. Taking inspiration from changes in society around him, Saint Laurent adapted his designs over the years. Starting his career designing custom-made clothing worn by upper-class women, he shifted his focus to create clothing that more people would want to wear and could afford. He responded to contemporary changes of the time and pushed gender, class, and expressive boundaries of fashion. He created innovative, glamorous pantsuits for women, ready-to-wear clothing for the wider population, and high fashion inspired by what he saw young people wearing on the street. In 1971 Yves Saint Laurent summed this up with one sentence, “What I want to do is shock people, force them to think.” The exhibition features over 100 haute couture and ready-to-wear garments. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Media Guide 1 Contents

Tuesday 19th - Saturday 23rd June 2018 MEDIA GUIDE 1 CONTENTS WELCOME TO ROYAL ASCOT FROM HER MAJESTY’S REPRESENTATIVE 4 VISITOR INFORMATION 5 RACING AT ROYAL ASCOT 6 RECORD PRIZE MONEY OF £13.45 MILLION AT ASCOT IN 2018 7 ROYAL ASCOT 2017 REVIEW 8 ROYAL ASCOT 2018 ORDER OF RUNNING AND PRIZE MONEY 10 ROYAL ASCOT GROUP I ENTRIES 12 A GLOBAL EVENT: ROYAL ASCOT’S RACE PROGRAMME MILESTONES 14 THE WEATHERBYS HAMILTON STAYERS’ MILLION 16 FOUR BREEDERS’ CUP CHALLENGE RACES TO BE HELD AT ROYAL ASCOT IN 2018 17 WORLD HORSE RACING LAUNCHES THE ULTIMATE DIGITAL RACING EXPERIENCE 18 CUSTOMERS INVITED TO BET WITH ASCOT 19 2018 GOFFS LONDON SALE GIVEN A NEW LOOK AT SAME ADDRESS 20 THE ROAD TO QIPCO BRITISH CHAMPIONS DAY 21 THE BELL ÉPOQUE 22 VETERINARY FACILITIES, EQUINE AND JOCKEYS’ FACILITIES 26 CHRIS STICKELS, CLERK OF THE COURSE 27 BROADCASTERS AT ROYAL ASCOT 28 NEW AT ROYAL ASCOT 30 COMMONWEALTH FASHION EXCHANGE 31 ASCOT RACECOURSE SUPPORTS 32 SCULPTURES 34 SHOPPING: THE COLLECTION 39 PARTNERS & SUPPLIERS 42 ASCOT’S OFFICIAL PARTNERS 43 ASCOT’S OFFICIAL SPONSORS AND SUPPLIERS 46 FASHION & DRESS CODE 50 ASCOT LAUNCHES THE SEVENTH ANNUAL ROYAL ASCOT STYLE GUIDE 51 THE HISTORY OF FASHION AT ROYAL ASCOT - KEY DATES 52 THE ROYAL ASCOT MILLINERY COLLECTIVE 2018 54 ROYAL ASCOT DRESS CODE 56 FINE DINING AT ROYAL ASCOT 58 FINE DINING AT ROYAL ASCOT CONTINUES TO DIVERSIFY AND DELIGHT 59 ASCOT HISTORY 66 ASCOT STORIES AND OTHER PROMOTIONAL FILMS 67 ROYAL ASCOT - THE ROYAL PROCESSION 68 THE BOWLER HAT AND ASCOT 71 ROYAL ASCOT FACTS AND FIGURES 72 ASCOT RACECOURSE -

Fashion Design Studio

PRECISION EXAMS Fashion Design Studio EXAM INFORMATION DESCRIPTION Exam Number This course explores how fashion influences everyday life 355 and introduces students to the fashion industry. Topics Items covered include: fashion fundamentals, elements and 59 principles of design, textiles, consumerism, and fashion Points related careers, with an emphasis on personal 69 application. FCCLA and/or DECA may be an integral Prerequisites part of this course. NONE Recommended Course Length ONE SEMESTER National Career Cluster ARTS, A/V TECHNOLOGY & COMMUNICATIONS HUMAN SERVICES EXAM BLUEPRINT MARKETING STANDARD PERCENTAGE OF EXAM Performance Standards 1 - Fashion Fundamentals 37% INCLUDED (OPTIONAL) 2 - Principles & Elements 27% Certificate Available 3 - Textiles 16% YES 4 - Consumer Strategies 11% 5 - Personal Fashion Characteristics 9% Fashion Design Studio STANDARD 1 STUDENTS WILL EXPLORE THE FUNDAMENTALS OF FASHION Objective 1 Identify why we wear clothes. 1. Protection – clothing that provides physical safeguards to the body, preventing harm from climate and environment. 2. Identification – clothing that establishes who someone is, what they do, or to which group(s) they belong. 3. Modesty – covering the body according to the code of decency established by society. 4. Status – establishing one’s position or rank in relation to others. 5. Adornment – using individual wardrobe to add decoration or ornamentation. Objective 2 Define common terminology. 1. Common Terminology. 1. Accessories – articles added to complete or enhance an outfit. Shoes, belts, handbags, jewelry, etc. 2. Apparel – all men's, women's, and children's clothing. 3. Avant-garde – wild and daring designs that are unconventional and startling. Usually disappear after a few years. 4. Classic – item of clothing that satisfies a basic need and continues to be in fashion acceptance over an extended period of time. -

Course Syllabus & Itinerary, THTR 216, Maymester 2015 the Art

Course Syllabus & Itinerary, THTR 216, Maymester 2015 The Art, History, & Business of London Fashion We will explore many facets of the business of style that make London one of the most cutting-edge and influential fashion capitals of the world. Our study will begin with an overview of fashion history and its connection to the fine and decorative arts. We will learn about the origins of Haute Couture, from its roots in England and France in the 19th century, to today’s well known designers and trendsetters who have kept this cosmopolitan city at the forefront of the industry. Dynamic British designers from the 20th and 21st century at the heart of our study, who have continually pushed boundaries and changed rules of etiquette in their quest for fashion to mirror political, economic, and sociopolitical changes in society, include: Charles Frederick Worth, considered to be the father of Haute Couture; Mary Quant and her mini-skirt revolution; Vivienne Westwood and her influence on the world of punk fashion; Alexander McQueen and his creation of artful garments; and Stella McCartney and her ethical, sustainable approach to design. Excursions will include trips to: world renowned museums, to study works of fine and decorative art and historic examples of clothing; theatrical performances, to compare the theatricality of stage costumes and the principles of stage design to both runway and everyday fashion; the Making of Harry Potter, to see how designers create artful film designs; and a variety of commercial fashion venues, in which contemporary -

REPEAL ASSOCATION..Wps

REPEAL ASSOCATION. Detroit-25 th July, 1844 To Daniel O’Donnell, Esq. M.P. Sir--The Detroit repealers beg leave respectfully to accompany their address by a mite of contribution towards the fine imposed on you, and solicit the favour of being allowed to participate in its payment. They would remit more largely, but are aware that others will also claim a like privilege. I am directed therefore to send you £20, and to solicit your acceptance of it towards the above object. We lately send 100/., to the Repeal Association, and within the past year another sum of 55/. Should there be any objection to our present request on your part or otherwise, we beg of you to apply it at your own discretion. I have the honour, Sir, to be your humble servant. H.H. Emmons, Corrres. Sec. Detroit Repeal Association. Contributers to the £20 send. C.H.Stewart, Dublin. Denis Mullane, Mallow, Co. Cork. Michael Dougherty, Newry. James Fitzmorris, Clonmel. Dr. James C. White, Mallow. James J. Hinde, Galway. John O’Callaghan, Braney, Co. Cork, one of the 1798 Patriots. (This could be Blarney). F.M. Grehie. Waterford. Michael Mahon, Limerick. George Gibson, Detroit. Christopher Cone, Tyrone, John Woods, Meath. Mr. and Mrs Hugh O’Beirne, Leitrim. James Leddy, Cavan. John Wade, Dublin, Denis O’Brien, Co. Kilkenny. James Collins, Omagh, Tyrone. Charles Moran, Detroit. Michael Kennedy, Waterford. Cornelius Dougherty, Tipperary. Thomas Sullivan, Cavan. Daniel Brislan, Tipperary. James Higgins, Kilkenny, Denis Lanigan, Kilkenny, John Sullivan, Mallow. Terence Reilly, Cavan, John Manning, Queens County. John Bermingham, Clare. Patrick MacTierney, Cavan. -

Department of Art & Design

Whitburn Academy Department of Art & Design Art & Design Studies Learners Higher: Art & Design Studies Design Analyse the factors influencing designers and design practice by Booklet Fashion 1.1 Describing how designers use a range of design materials, techniques and technology in their work 1.2 Analysing the impact of the designers’ creative choices in a range of design work 1.3 Analysing the impact of social and cultural influences on selected designers and their design practice. A study of Coco Chanel Day dress, ca. 1924 Gabrielle Theater suit, 1938, Gabrielle Evening dress, ca. 1926–27 "Coco" Chanel (French, 1883–1971) "Coco" Chanel (French, 1883– Attributed to Gabrielle "Coco" Wool 1971) Silk Chanel (French, 1883–1971) Silk, metallic threads, sequins What is Fashion Design? Fashion design is a form of art dedicated to the creation of clothing and other lifestyle accessories. Modern fashion design is divided into two basic categories: haute couture and ready-to-wear. The haute couture collection is dedicated to certain customers and is custom sized to fit these customers exactly. In order to qualify as a haute couture house, a designer has to be part of the Syndical Chamber for Haute Couture and show a new collection twice a year presenting a minimum of 35 different outfits each time. Ready-to-wear collections are standard sized, not custom made, so they are more suitable for large production runs. They are also split into two categories: designer/creator and confection collections. Designer collections have a higher quality and finish as well as an unique design. They often represent a certain philosophy and are created to make a statement rather than for sale. -

Bespoke Tailoring: the Luxury and Heritage We Can Afford

University of Huddersfield Repository Almond, Kevin Bespoke Tailoring: The Luxury and Heritage we can afford Original Citation Almond, Kevin (2011) Bespoke Tailoring: The Luxury and Heritage we can afford. In: Fashion Colloquia London 2011, 21st - 22nd September 2011, London College of Fashion. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/11539/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ BESPOKE TAILORING: THE LUXURY AND HERITAGE WE CAN AFFORD Slide 1 PLACE OF PUBLICATION: THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TECHNOLOGY, KNOWLEDGE AND SOCIETY KEY WORDS: Bespoke, Tailor, Conflict, Luxury, Heritage, Technology, Fashion ABSTRACT This article investigates the conflict between hand crafted bespoke tailoring and computerised mass market tailoring in the UK, in order to assess the overall place for this traditional technique within fashion design. -

Fashion Design in the 21St Century A

TECHNOLOGY AND CREATIVITY: FASHION DESIGN IN THE 21 ST CENTURY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by MARY RUPPERT-STROESCU Dr. Jana Hawley, Dissertation Supervisor May 2009 © Copyright by Mary Ruppert-Stroescu 2009 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled TECHNOLOGY AND CREATIVITY: FASHION DESIGN IN THE 21 ST CENTURY Presented by Mary Ruppert-Stroescu, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________ Dr. Kitty Dickerson _______________________________ Dr. Jana Hawley _______________________________ Dr. Laurel Wilson _______________________________ Dr. Julie Caplow I dedicate this dissertation to my sons, Matei and Ioan Stroescu, who are continuous sources of inspiration and joy. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Dr. Jana Hawley, for inspiring and challenging me without fail. I will remain eternally grateful as well to Dr. Laurel Wilson & Dr. Kitty Dickerson, for their patience, insight, and guidance. I must also recognize Dr. Jean Hamilton, whose courses I will never forget because her ability to communicate a passion for research sparked my path to this dissertation. Dr. Julie Caplow built upon the appreciation for qualitative research that began with Dr. Hamilton, and I thank her for her support. Without Peter Carman I would not have had a platform for connecting with the French industry interviewees. I thank my family for their support, and all those who took time from their professional obligations to discuss technology and creativity with me.