<I>Mecaster Fourneli</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handbook of Texas Cretaceous Fossils

University of Texas Bulletin No. 2838: October 8, 1928 HANDBOOK OF TEXAS CRETACEOUS FOSSILS B y W. S. ADKINS Bureau of Economic Geology J. A. Udden, Director E. H. Sellards, Associate Director PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY FOUR TIMES A MONTH, AND ENTERED AS SECOND-CLASS MATTER AT THE POSTOFFICE AT AUSTIN, TEXAS. UNDER THE ACT OF AUGUST 24. 1912 The benefits of education and of useful knowledge, generally diffused through a community, are essential to the preservation of a free govern m en t. Sam Houston Cultivated mind is the guardian genius of democracy. It is the only dictator that freemen acknowl edge and the only security that free men desire. Mirabeau В. Lamar CONTENTS P age Introduction __________________________________________________ 5 Summary of Formation Nomenclature_______________________ 6 Zone Markers and Correlation_______________________________ 8 Types of Texas Cretaceous Fossils___________________________ 36 Bibliography ________________________________________________ 39 L ist and Description of Species_________________________________ 46 P lants ______________________________________________________ 46 Thallophytes ______________________________________________ 46 Fungi __________________________________________________ 46 Algae __________________________________________________ 47 Pteridophytes ____________________________________________ 47 Filices __________________________________________________ 47 Spermatophytes __________________________________________ 47 Gymnospermae _________________________________________ -

First Record of the Irregular Sea Urchin Lovenia Cordiformis (Echinodermata: Spatangoida: Loveniidae) in Colombia C

Muñoz and Londoño-Cruz Marine Biodiversity Records (2016) 9:67 DOI 10.1186/s41200-016-0022-9 RECORD Open Access First record of the irregular sea urchin Lovenia cordiformis (Echinodermata: Spatangoida: Loveniidae) in Colombia C. G. Muñoz1* and E. Londoño-Cruz1,2 Abstract Background: A first record of occurrence of the irregular sea urchin Lovenia cordiformis in the Colombian Pacific is herein reported. Results: We collected one specimen of Lovenia cordiformis at Gorgona Island (Colombia) in a shallow sandy bottom next to a coral reef. Basic morphological data and images of the collected specimen are presented. The specimen now lies at the Echinoderm Collection of the Marine Biology Section at Universidad del Valle (Cali, Colombia; Tag Code UNIVALLE: CRBMeq-UV: 2014–001). Conclusions: This report fills a gap in and completes the distribution of the species along the entire coast of the Panamic Province in the Tropical Eastern Pacific, updating the echinoderm richness for Colombia to 384 species. Keywords: Lovenia cordiformis, Loveniidae, Sea porcupine, Heart urchin, Gorgona Island Background continental shelf of the Pacific coast of Colombia, filling Heart shape-bodied sea urchins also known as sea por- in a gap of its coastal distribution in the Tropical Eastern cupines (family Loveniidae), are irregular echinoids char- Pacific (TEP). acterized by its secondary bilateral symmetry. Unlike most sea urchins, features of the Loveniidae provide dif- Materials and methods ferent anterior-posterior ends, with mouth and anus lo- One Lovenia cordiformis specimen was collected on cated ventrally and distally on an oval-shaped horizontal October 19, 2012 by snorkeling during low tide at ap- plane. -

(Spatangoida) Abatus Agassizii

fmicb-11-00308 February 27, 2020 Time: 15:33 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 28 February 2020 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00308 Characterization of the Gut Microbiota of the Antarctic Heart Urchin (Spatangoida) Abatus agassizii Guillaume Schwob1,2*, Léa Cabrol1,3, Elie Poulin1 and Julieta Orlando2* 1 Laboratorio de Ecología Molecular, Instituto de Ecología y Biodiversidad, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2 Laboratorio de Ecología Microbiana, Departamento de Ciencias Ecológicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 3 Aix Marseille University, Univ Toulon, CNRS, IRD, Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography (MIO) UM 110, Marseille, France Abatus agassizii is an irregular sea urchin species that inhabits shallow waters of South Georgia and South Shetlands Islands. As a deposit-feeder, A. agassizii nutrition relies on the ingestion of the surrounding sediment in which it lives barely burrowed. Despite the low complexity of its feeding habit, it harbors a long and twice-looped digestive tract suggesting that it may host a complex bacterial community. Here, we characterized the gut microbiota of specimens from two A. agassizii populations at the south of the King George Island in the West Antarctic Peninsula. Using a metabarcoding approach targeting the 16S rRNA gene, we characterized the Abatus microbiota composition Edited by: David William Waite, and putative functional capacity, evaluating its differentiation among the gut content Ministry for Primary Industries, and the gut tissue in comparison with the external sediment. Additionally, we aimed New Zealand to define a core gut microbiota between A. agassizii populations to identify potential Reviewed by: Cecilia Brothers, keystone bacterial taxa. -

X-Ray Microct Study of Pyramids of the Sea Urchin Lytechinus Variegatus

Journal of Structural Biology Journal of Structural Biology 141 (2003) 9–21 www.elsevier.com/locate/yjsbi X-ray microCT study of pyramids of the sea urchin Lytechinus variegatus S.R. Stock,a,* S. Nagaraja,b J. Barss,c T. Dahl,c and A. Veisc a Institute for Bioengineering and Nanoscience in Advanced Medicine, Northwestern University, 303 E. Chicago Avenue, Tarry 16-717, Chicago, IL 60611-3008, USA b School of Mechanical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA c Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL 60611, USA Received 19 June 2002, and in revised form 23 September 2002 Abstract This paper reports results of a novel approach, X-ray microCT, for quantifying stereom structures applied to ossicles of the sea urchin Lytechinus variegatus. MicroCT, a high resolution variant of medical CT (computed tomography), allows noninvasive mapping of microstructure in 3-D with spatial resolution approaching that of optical microscopy. An intact pyramid (two demi- pyramids, tooth epiphyses, and one tooth) was reconstructed with 17 lm isotropic voxels (volume elements); two individual demipyramids and a pair of epiphyses were studied with 9–13 lm isotropic voxels. The cross-sectional maps of a linear attenuation coefficient produced by the reconstruction algorithm showed that the structure of the ossicles was quite heterogeneous on the scale of tens to hundreds of micrometers. Variations in magnesium content and in minor elemental constitutents could not account for the observed heterogeneities. Spatial resolution was insufficient to resolve the individual elements of the stereom, but the observed values of the linear attenuation coefficient (for the 26 keV effective X-ray energy, a maximum of 7.4 cmÀ1 and a minimum of 2cmÀ1 away from obvious voids) could be interpreted in terms of fractions of voxels occupied by mineral (high magnesium calcite). -

SI Appendix for Hopkins, Melanie J, and Smith, Andrew B

Hopkins and Smith, SI Appendix SI Appendix for Hopkins, Melanie J, and Smith, Andrew B. Dynamic evolutionary change in post-Paleozoic echinoids and the importance of scale when interpreting changes in rates of evolution. Corrections to character matrix Before running any analyses, we corrected a few errors in the published character matrix of Kroh and Smith (1). Specifically, we removed the three duplicate records of Oligopygus, Haimea, and Conoclypus, and removed characters C51 and C59, which had been excluded from the phylogenetic analysis but mistakenly remain in the matrix that was published in Appendix 2 of (1). We also excluded Anisocidaris, Paurocidaris, Pseudocidaris, Glyphopneustes, Enichaster, and Tiarechinus from the character matrix because these taxa were excluded from the strict consensus tree (1). This left 164 taxa and 303 characters for calculations of rates of evolution and for the principal coordinates analysis. Other tree scaling methods The most basic method for scaling a tree using first appearances of taxa is to make each internal node the age of its oldest descendent ("stand") (2), but this often results in many zero-length branches which are both theoretically questionable and in some cases methodologically problematic (3). Several methods exist for modifying zero-length branches. In the case of the results shown in Figure 1, we assigned a positive length to each zero-length branch by having it share time equally with a preceding, non-zero-length branch (“equal”) (4). However, we compared the results from this method of scaling to several other methods. First, we compared this with rates estimated from trees scaled such that zero-length branches share time proportionally to the amount of character change along the branches (“prop”) (5), a variation which gave almost identical results as the method used for the “equal” method (Fig. -

Fossil Spatangoid Echinoids of Cuba

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO PALEOBIOLOGY • NUMBER 55 Fossil Spatangoid Echinoids of Cuba Porter M. Kier SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1984 ABSTRACT Kier, Porter M. Fossil Spatangoid Echinoids of Cuba. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, number 55, 336 pages, frontispiece, 45 figures, 90 plates, 6 tables, 1984.—The fossil spatangoid echinoids of Cuba are described based for the most part on specimens in the Sanchez Roig Collection. Seventy-nine species are recognized including 10 from the Late Cretaceous, 36 from the Eocene, 20 from the Oligocene-Miocene, 11 from the Miocene, and 2 of uncertain age. Three of the Eocene species are new: Schizas ter forme III, Linthia monteroae, and Antillaster albeari. A new genus of schizasterid is described, Caribbaster, with the Eocene Prenaster loveni Cotteau as the type-species. A new Asterostoma, A. pawsoni, is described from the Eocene of Jamaica. The Eocene age of the Cuban echinoid-bearing localities is confirmed by the presence outside Cuba of many ofthe same species in beds dated on other fossils. Some evidence supports the Miocene determinations, but the echinoids are of little assistance in resolving the question whether the Cuban beds attributed to the Oligocene are Oligocene or Miocene. Cuban, and in general, the Caribbean Tertiary echinoid faunas are distinct from those in Europe and the Mediterranean. Many genera are confined to the Caribbean. The Cuban fauna is also different from that found nearby in Florida. This difference may be due to a suggested greater depth of water in Cuba. Se describen los equinoideos espatangoideos de Cuba, incluyendo los es- pecimenes de la Coleccion Sanchez Roig. -

For Peer Review

Page 1 of 40 Geological Journal Page 1 of 32 1 2 3 Neogene echinoids from the Cayman Islands, West Indies: regional 4 5 6 implications 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 11 STEPHEN K. DONOVAN *, BRIAN JONES and DAVID A. T. HARPER 12 13 14 15 1Department of Geology, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, the Netherlands 16 17 2Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, T6G 2E3 18 For Peer Review 19 3 20 Department of Earth Sciences, Durham University, Durham, UK 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 *Correspondence to: S. K. Donovan, Department of Geology, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, 49 50 Darwinweg 2, 2333 CR Leiden, the Netherlands. 51 52 E-mail: [email protected] 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/gj Geological Journal Page 2 of 40 Page 2 of 32 1 2 3 The first fossil echinoids are recorded from the Cayman Islands. A regular echinoid, Arbacia? sp., the 4 5 spatangoids Brissus sp. cf. B. oblongus Wright and Schizaster sp. cf. S. americanus (Clark), and the 6 7 clypeasteroid Clypeaster sp. are from the Middle Miocene Cayman Formation. Test fragments of the 8 9 mellitid clypeasteroid, Leodia sexiesperforata (Leske), are from the Late Pleistocene Ironshore 10 11 Formation. Miocene echinoids are preserved as (mainly internal) moulds; hence, all species are left 12 13 14 in open nomenclature because of uncertainties regarding test architecture. -

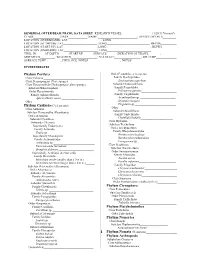

Benthic Data Sheet

DEMERSAL OTTER/BEAM TRAWL DATA SHEET RESEARCH VESSEL_____________________(1/20/13 Version*) CLASS__________________;DATE_____________;NAME:___________________________; DEVICE DETAILS_________ LOCATION (OVERBOARD): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________ LOCATION (AT DEPTH): LAT_______________________; LONG_____________________________; DEPTH___________ LOCATION (START UP): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________;.DEPTH__________ LOCATION (ONBOARD): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________ TIME: IN______AT DEPTH_______START UP_______SURFACE_______.DURATION OF TRAWL________; SHIP SPEED__________; WEATHER__________________; SEA STATE__________________; AIR TEMP______________ SURFACE TEMP__________; PHYS. OCE. NOTES______________________; NOTES_______________________________ INVERTEBRATES Phylum Porifera Order Pennatulacea (sea pens) Class Calcarea __________________________________ Family Stachyptilidae Class Demospongiae (Vase sponge) _________________ Stachyptilum superbum_____________________ Class Hexactinellida (Hyalospongia- glass sponge) Suborder Subsessiliflorae Subclass Hexasterophora Family Pennatulidae Order Hexactinosida Ptilosarcus gurneyi________________________ Family Aphrocallistidae Family Virgulariidae Aphrocallistes vastus ______________________ Acanthoptilum sp. ________________________ Other__________________________________________ Stylatula elongata_________________________ Phylum Cnidaria (Coelenterata) Virgularia sp.____________________________ Other_______________________________________ -

Morphological Variations, Patterns of Frontal Ambulacrum Pores And

Pak. J. Sci. Ind. Res. Ser. B: Biol. Sci. 2011 54 (1) 41-46 Morphological Variations, Patterns of Frontal Ambulacrum Pores and Paleoecology of Heteraster renngarteni Poretzkaja (Echinoidea: Spatangoida) from Aptian Sediments of Baghin Area, Kerman, Iran Mohammed Raza Vaziri* and Ahmad Lotfabad Arab Geology Department, Faculty of Sciences, Shahid Bahonar University, Kerman, Islamic Republic of Iran (received July 30, 2009; revised July 25, 2010; accepted August 30, 2010) Abstract. Detailed macro- and microscopic analysis of spatangoid echinoid, Heteraster renngarteni Poretzkaja showed a remarkable variation in morphology and alternation of short and long pores in the frontal ambu- lacrum. The differentiation of pores in the frontal ambulacrum has been interpreted as an adaptive strategy for survival in a shallow shelf environment whereas, variation in morphology appears to be influenced mainly by grain size of the substrate. Keywords: echinoids, Iran, ambulacrum pores, Heteraster renngarteni, Cretaceous, Kerman Introduction of spatangoids (Villier et al., 2001), there is no revised Phylogenetic schemes for spatangoid relationships have monograph of the genus. Description of Iranian mate- been proposed by Smith (1984) and more recently by rial will improve knowledge about the genus and help Neumann (1999). The order Spatangoida appeared first compare it with the specimens reported from the other in the lowermost Cretaceous (Berriasian). Within the parts of the world. spatangoids, the family Toxasteridae originated probably H. renngarteni, on which this study focused, is a rather from a disasteroid ancestor. During the Berriasian to the large toxasterid echinoid and occurs abundantly in Aptian, diversification of the family led to appearance Aptian marls of Baghin area, west of Kerman, Iran. -

Arbacia Lixula (Linnaeus, 1758)

Arbacia lixula (Linnaeus, 1758) AphiaID: 124249 OURIÇO-NEGRO Animalia (Reino) > Echinodermata (Filo) > Echinozoa (Subfilo) > Echinoidea (Classe) > Euechinoidea (Subclasse) > Carinacea (Infraclasse) > Echinacea (Superordem) > Arbacioida (Ordem) > Arbaciidae (Familia) Vasco Ferreira Vasco Ferreira Estatuto de Conservação Sinónimos Arbacia aequituberculata (Blainville, 1825) Arbacia australis Lovén, 1887 Arbacia grandinosa (Valenciennes, 1846) Arbacia pustulosa (Leske, 1778) Cidaris pustulosa Leske, 1778 Echinocidaris (Agarites) loculatua (Blainville, 1825) Echinocidaris (Tetrapygus) aequituberculatus (Blainville, 1825) Echinocidaris (Tetrapygus) grandinosa (Valenciennes, 1846) 1 Echinocidaris (Tetrapygus) pustulosa (Leske, 1778) Echinocidaris aequituberculata (Blainville, 1825) Echinocidaris grandinosa (Valenciennes, 1846) Echinocidaris loculatua (Blainville, 1825) Echinocidaris pustulosa (Leske, 1778) Echinus aequituberculatus Blainville, 1825 Echinus equituberculatus Blainville, 1825 Echinus grandinosus Valenciennes, 1846 Echinus lixula Linnaeus, 1758 Echinus loculatus Blainville, 1825 Echinus neapolitanus Delle Chiaje, 1825 Echinus pustulosus (Leske, 1778) Referências additional source Hayward, P.J.; Ryland, J.S. (Ed.). (1990). The marine fauna of the British Isles and North-West Europe: 1. Introduction and protozoans to arthropods. Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK. ISBN 0-19-857356-1. 627 pp. [details] basis of record Hansson, H.G. (2001). Echinodermata, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list -

The Impact of Morphometric Scheme, Temporal Scale, and Taxonomic Level in Spatangoid Echinoids

In Press, Paleobiology Assessing the robustness of disparity estimates: the impact of morphometric scheme, temporal scale, and taxonomic level in spatangoid echinoids Loïc Villier and Gunther J. Eble RRH: ROBUSTNESS OF DISPARITY IN SPATANGOIDS LRH: LOÏC VILLIER AND GUNTHER J. EBLE Villier and Eble, p. 2 Abstract. – The joint quantification of disparity and diversity is an important aspect of recent macroevolutionary studies, and is usually motivated by theoretical considerations on the pace of innovation and the filling of morphospace. In practice, varying protocols of data collection and analysis have rendered comparisons among studies difficult. The basic question remains, how sensitive is any given disparity signal to different aspects of sampling and data analysis? Here we address this issue in the context of the radiation of the echinoid order Spatangoida during the Cretaceous. We compare patterns at the genus- and species-level, with time subdivision into subepochs and into stages, and with morphological sampling based on landmarks, traditional morphometrics, and discrete characters. In terms of temporal scale, similarity of disparity pattern accrues despite a change in temporal resolution. Different morphometric methods, however, produce somewhat different signals early in the radiation. Both the landmark analysis and the discrete character analysis suggest relatively high early disparity, whereas the analysis based on traditional morphometrics records a much lower value. This difference appears to reflect primarily the measurement of different aspects of overall morphology. Notwithstanding, a general deceleration in morphological diversification is apparent at both the genus and the species level. Moreover, inclusion or exclusion of the sister-order Holasteroida and stem-group Disasteroida in the reference morphospace did not affect proportional Villier and Eble, p. -

Paleogenomics of Echinoids Reveals an Ancient Origin for the Double-Negative Specification of Micromeres in Sea Urchins

Paleogenomics of echinoids reveals an ancient origin for the double-negative specification of micromeres in sea urchins Jeffrey R. Thompsona,1, Eric M. Erkenbrackb, Veronica F. Hinmanc, Brenna S. McCauleyc,d, Elizabeth Petsiosa, and David J. Bottjera aDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089; bDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511; cDepartment of Biological Sciences, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213; and dHuffington Center on Aging, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030 Edited by Douglas H. Erwin, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Neil H. Shubin January 31, 2017 (received for review August 2, 2016) Establishing a timeline for the evolution of novelties is a common, methods thus provide a rigorous methodology in which to examine unifying goal at the intersection of evolutionary and developmental gene expression datasets, and ultimately animal body plan evolu- biology. Analyses of gene regulatory networks (GRNs) provide the tion (11), within the context of evolutionary time. After genomic ability to understand the underlying genetic and developmental novelties underlying differential body plan development have been mechanisms responsible for the origin of morphological structures identified, we can then consider the rates at which these novelties both in the development of an individual and across entire evolution- arise, and the rates at which GRNs evolve. Achieving this end ary lineages. Accurately dating GRN novelties, thereby establishing requires an explicit timeline in which to explore GRN evolution. a timeline for GRN evolution, is necessary to answer questions In a phylogenetically informed, comparative framework, it is about the rate at which GRNs and their subcircuits evolve, and to possible to infer where on a phylogenetic tree and when, in deep tie their evolution to paleoenvironmental and paleoecological time, GRN innovations are likely to have first arisen.