Scoones and Cou ... Dry South of Zimbabwe.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promotion of Climate-Resilient Lifestyles Among Rural Families in Gutu

Promotion of climate-resilient lifestyles among rural families in Gutu (Masvingo Province), Mutasa (Manicaland Province) and Shamva (Mashonaland Central Province) Districts | Zimbabwe Sahara and Sahel Observatory 26 November 2019 Promotion of climate-resilient lifestyles among rural families in Gutu Project/Programme title: (Masvingo Province), Mutasa (Manicaland Province) and Shamva (Mashonaland Central Province) Districts Country(ies): Zimbabwe National Designated Climate Change Management Department, Ministry of Authority(ies) (NDA): Environment, Water and Climate Development Aid from People to People in Zimbabwe (DAPP Executing Entities: Zimbabwe) Accredited Entity(ies) (AE): Sahara and Sahel Observatory Date of first submission/ 7/19/2019 V.1 version number: Date of current submission/ 11/26/2019 V.2 version number A. Project / Programme Information (max. 1 page) ☒ Project ☒ Public sector A.2. Public or A.1. Project or programme A.3 RFP Not applicable private sector ☐ Programme ☐ Private sector Mitigation: Reduced emissions from: ☐ Energy access and power generation: 0% ☐ Low emission transport: 0% ☐ Buildings, cities and industries and appliances: 0% A.4. Indicate the result ☒ Forestry and land use: 25% areas for the project/programme Adaptation: Increased resilience of: ☒ Most vulnerable people and communities: 25% ☒ Health and well-being, and food and water security: 25% ☐ Infrastructure and built environment: 0% ☒ Ecosystem and ecosystem services: 25% A.5.1. Estimated mitigation impact 399,223 tCO2eq (tCO2eq over project lifespan) A.5.2. Estimated adaptation impact 12,000 direct beneficiaries (number of direct beneficiaries) A.5. Impact potential A.5.3. Estimated adaptation impact 40,000 indirect beneficiaries (number of indirect beneficiaries) A.5.4. Estimated adaptation impact 0.28% of the country’s total population (% of total population) A.6. -

The Policy and Legislative Framework for Zimbabwe's Fast Track Land Reform Programme and Its Implications on Women's Rights

The Policy and Legislative Framework for Zimbabwe’s Fast Track Land Reform Programme and its Implications on Women’s Rights to Agricultural Land BY MAKANATSA MAKONESE Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Law Southern and East African Regional Centre for Women’s Law (SEARCWL) University of Zimbabwe Supervisors Professor Julie Stewart and Professor Anne Hellum 2017 i Dedication To my two mothers, Betty Takaidza Nhengu (Gogo Dovi) and Felistas Dzidzai Nhengu (Gogo Banana) - Because of you, I believe in love. To my late brothers Thompson, Thomas Hokoyo and Munyenyiwa Nhengu; I know you would have been so proud of this accomplishment. To my late father, VaMusarinya, In everything I do, I always remember that “ndiri mwana wa Ticha Nhengu” ii Acknowledgments For any work of this magnitude, there are always so many people who contribute in many but unique ways in making the assignment possible. If I were to mention all the people that played a part in small and big ways in making this dream a reality, it would be such a long list. To all of you, I say, thank you. I am grateful to my supervisors, Professor Julie Stewart and Professor Anne Hellum for your guidance, patience, commitment, for the occasional “wake-up” slap and for meticulously combing through the many chapters and versions of this thesis which I produced along the way. Thank you for believing in me and for assuring me that with hard work, I could do it. I would also like to thank Professor William Derman of the Norwegian University of Life Sciences for his advice on my thesis and for providing me with volumes of useful reading material on the Zimbabwean land question. -

Zimbabwe Community COP20

COMMUNITY COP20 ZIMBABWE COMMUNITY PRIORITIES PEPFAR COUNTRY OPERATIONAL PLAN 2020 Introduction Civil society and people living with and affected by HIV in Zimbabwe appreciate the increased PEPFAR budget support in COP20 by US$63m. Zimbabwe remains committed to ending HIV/AIDS by 2030 despite its current social, economic and political challenges. While Zimbabwe is celebrated for achieving more with less, the operating environment has deteriorated significantly over the past 12 months. Power outage, cash and fuel shortages have made project implementation costly and unsustainable. Throughout this period, disbursements to health remained unpredictable and below budget allocation with just over 80% of the budget allocated being disbursed. In 2018, 64% of the Government of Zimbabwe (GOZ) budget allocation for Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) was for salaries according to the Resource Mapping Report, 20191. This leaves the larger burden of important health system components (e.g. commodity needs and distribution, laboratory sample transportation, and health facility operational costs, etc.) in the hands of external funding from donors. Domestic and External Funding Cost Drivers: Source Resource Mapping 2019 1. Resource Mapping 2019 Report 2 PEOPLE’S COP20 – COMMUNITY PRIORITIES – ZIMBABWE Despite support from Zimbabwe’s health development partners, Art Refill Distribution -OFCAD) and strategies of care as piloted the consolidated total funding still falls short of projected by BHASO in partnership with MSF and MoHCC in Mwenezi requirements necessary to fully implement the national health District with excellent retention in care results; strategy particularly supporting human resources for health. + Improve levels of stocks of commodities especially VL reagents, adult send line treatment, opportunistic infections drugs and As of December 2018, the GOZ’s allocation to health was 7.3% of paediatric treatment; the national budget, well below the Abuja Target of 15%. -

Zimbabwe Market Study: Masvingo Province Report

©REUTERS/Philimon Bulawayo Bulawayo ©REUTERS/Philimon R E S E A R C H T E C H N I C A L A S S I S T A N C E C E N T E R January 2020 Zimbabwe Market Study: Masvingo Province Report Dominica Chingarande, Gift Mugano, Godfrey Chagwiza, Mabel Hungwe Acknowledgments The Research team expresses its gratitude to the various stakeholders who participated in this study in different capacities. Special gratitude goes to the District Food and Nutrition Committee members, the District Drought Relief Committee members, and various market actors in the province for providing invaluable local market information. We further express our gratitude to the ENSURE team in Masvingo for mobilizing beneficiaries of food assistance who in turn shared their lived experiences with food assistance. To these food assistance beneficiaries, we say thank you for freely sharing your experiences. Research Technical Assistance Center The Research Technical Assistance Center is a world-class research consortium of higher education institutions, generating rapid research for USAID to promote evidence-based policies and programs. The project is led by NORC at the University of Chicago in partnership with Arizona State University, Centro de Investigacin de la Universidad del Pacifico (Lima, Peru), Davis Management Group, the DevLab@Duke University, Forum One, the Institute of International Education, the Notre Dame Initiative for Global Development, Population Reference Bureau, the Resilient Africa Network at Makerere University (Kampala, Uganda), the United Negro College Fund, the University of Chicago, and the University of Illinois at Chicago. The Research Technical Assistance Center (RTAC) is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of contract no. -

University of Pretoria Etd – Nsingo, SAM (2005)

University of Pretoria etd – Nsingo, S A M (2005) - 181 - CHAPTER FOUR THE PROFILE, STRUCTURE AND OPERATIONS OF THE BEITBRIDGE RURAL DISTRICT COUNCIL INTRODUCTION This chapter describes the basic features of the Beitbridge District. It looks at the organisation of the Beitbridge Rural District Council and explores its operations as provided in the Rural District Councils Act of 1988 and the by-laws of council. The chapter then looks at performance measurement in the public sector and local government, in particular. This is followed by a discussion of democratic participation, service provision and managerial excellence including highlights of their relevance to this study. BEITBRIDGE DISTRICT PROFILE The Beitbridge District is located in the most southern part of Zimbabwe. It is one of the six districts of Matebeleland South province. It shares borders with Botswana in the west, South Africa in the south, Mwenezi District from the north to the east, and Gwanda District in the northwest. Its geographical area is a result of amalgamating the Beitbridge District Council and part of the Mwenezi- Beitbridge Rural District Council. The other part of the latter was amalgamated with the Mwenezi District to form what is now the Mwenezi District Council. Significant to note, from the onset, is that Beitbridge District is one of the least developed districts in Zimbabwe. Worse still, it is located in region five (5), which is characterized by poor rainfall and very hot conditions. As such, it is not suitable for crop farming, although this takes place through irrigation schemes. University of Pretoria etd – Nsingo, S A M (2005) - 182 - The district is made up of an undulating landscape with shrubs, isolated hills and four big rivers. -

An Agrarian History of the Mwenezi District, Zimbabwe, 1980-2004

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UWC Theses and Dissertations AN AGRARIAN HISTORY OF THE MWENEZI DISTRICT, ZIMBABWE, 1980-2004 KUDAKWASHE MANGANGA A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.PHIL IN LAND AND AGRARIAN STUDIES IN THE DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT, UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE November 2007 DR. ALLISON GOEBEL (QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY, CANADA) DR. FRANK MATOSE (PLAAS, UWC) ii ABSTRACT An Agrarian History of the Mwenezi District, Zimbabwe, 1980-2004 Kudakwashe Manganga M. PHIL Thesis, Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies, Department of Government, University of the Western Cape. The thesis examines continuity and change in the agrarian history of the Mwenezi district, southern Zimbabwe since 1980. It analyses agrarian reforms, agrarian practices and development initiatives in the district and situates them in the localised livelihood strategies of different people within Dinhe Communal Area and Mangondi Resettlement Area in lieu of the Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) since 2000. The thesis also examines the livelihood opportunities and challenges presented by the FTLRP to the inhabitants of Mwenezi. Land reform can be an opportunity that can help communities in drought prone districts like Mwenezi to attain food security and reduce dependence on food handouts from donor agencies and the government. The land reform presented the new farmers with multiple land use patterns and livelihood opportunities. In addition, the thesis locates the current programme in the context of previous post-colonial agrarian reforms in Mwenezi. It also emphasizes the importance of diversifying rural livelihood portfolios and argues for the establishment of smallholder irrigation schemes in Mwenezi using water from the Manyuchi dam, the fourth largest dam in Zimbabwe. -

Masvingo Province

School Level Province Ditsrict School Name School Address Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIKITA FASHU SCH BIKITA MINERALS CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIKITA MAMUTSE SECONDARY MUCHAKAZIKWA VILLAGE CHIEF BUDZI BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIRIVENGE MUPAMHADZI VILLAGE WARD 12 CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita BUDIRIRO VILLAGE 1 WARD 11 CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHENINGA B WARD 2, CHF;MABIKA, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIKWIRA BETA VILLAGE,CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE,WARD 16 Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHINYIKA VILLAGE 23 DEVURE WARD 26 Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIPENDEKE CHADYA VILLAGE, CHF ZIKI, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIRIMA RUGARE VILLAGE WARD 22, CHIEF;MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIRUMBA TAKAWIRA VILLAGE, WARD 9, CHF; MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHISUNGO MBUNGE VILLAGE WARD 21 CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIZONDO CHIZONDO HIGH,ZINDOVE VILLAGE,WARD 2,CHIEF MABIKA Secondary Masvingo Bikita FAMBIDZANAI HUNENGA VILLAGE Secondary Masvingo Bikita GWINDINGWI MABHANDE VILLAGE,CHF;MUKANGANWI, WRAD 13, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita KUDADISA ZINAMO VILLAGE, WARD 20,CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita KUSHINGIRIRA MUKANDYO VILLAGE,BIKITA SOUTH, WARD 6 Secondary Masvingo Bikita MACHIRARA CHIWA VILLAGE, CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE Secondary Masvingo Bikita MANGONDO MUSUKWA VILLAGE WARD 11 CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita MANUNURE DEVURE RESETTLEMENT VILLAGE 4A CHIEF BUDZI Secondary Masvingo Bikita MARIRANGWE HEADMAN NEGOVANO,CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE Secondary Masvingo Bikita MASEKAYI(BOORA) -

An Agrarian History of the Mwenezi District, Zimbabwe, 1980-2004

AN AGRARIAN HISTORY OF THE MWENEZI DISTRICT, ZIMBABWE, 1980-2004 KUDAKWASHE MANGANGA A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.PHIL IN LAND AND AGRARIAN STUDIES IN THE DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT, UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE November 2007 DR. ALLISON GOEBEL (QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY, CANADA) DR. FRANK MATOSE (PLAAS, UWC) ii ABSTRACT An Agrarian History of the Mwenezi District, Zimbabwe, 1980-2004 Kudakwashe Manganga M. PHIL Thesis, Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies, Department of Government, University of the Western Cape. The thesis examines continuity and change in the agrarian history of the Mwenezi district, southern Zimbabwe since 1980. It analyses agrarian reforms, agrarian practices and development initiatives in the district and situates them in the localised livelihood strategies of different people within Dinhe Communal Area and Mangondi Resettlement Area in lieu of the Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) since 2000. The thesis also examines the livelihood opportunities and challenges presented by the FTLRP to the inhabitants of Mwenezi. Land reform can be an opportunity that can help communities in drought prone districts like Mwenezi to attain food security and reduce dependence on food handouts from donor agencies and the government. The land reform presented the new farmers with multiple land use patterns and livelihood opportunities. In addition, the thesis locates the current programme in the context of previous post-colonial agrarian reforms in Mwenezi. It also emphasizes the importance of diversifying rural livelihood portfolios and argues for the establishment of smallholder irrigation schemes in Mwenezi using water from the Manyuchi dam, the fourth largest dam in Zimbabwe. -

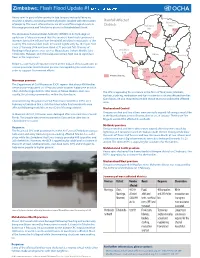

ZIM-Infographic-Flood-06 A4 07Feb2014 Zimbabwe Flash Flood - February 2014.Ai

¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¦ § ¨ © ¡ ¥ Heavy rains in parts of the country in late January and early February resulted in deaths and displacement of people, coupled with destruction Rainfall A!ected Mashonaland of property. The worst a!ected areas are Chivi and Masvingo districts in Districts Mashonaland Central Masvingo province and Tsholotsho district in Matabeleland North. West Shamva The Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA) in its hydrological Makonde Binga update on 5 February warned that the country’s dam levels continue to Harare increase due to the in"ows from the rainfall activities in most parts of the Gokwe South country. The national dam levels increased signicantly by 10.29 per cent since 27 January 2014 and now stand at 71 per cent full. Chances of Mashonaland "ooding in "ood prone areas such as Muzarabani, Gokwe, Middle Sabi, Matabeleland East Tsholotsho, Malapati and Chikwalakwala remain high due to signicant North Midlands Manicaland "ows in the major rivers. Tsholotsho Gutu Bulawayo Below is a summary of reports received on the impact of incessant rains in Masvingo Chivi various provinces. Humanitarian partners are appealing for assistance in Matabeleland Masvingo order to support Government e!orts. Mangwe South A!ected districts Gwanda Mwenezi Chiredzi Masvingo province The Department of Civil Protection (DCP) reports that about 400 families needed to be evacuated on 3 February while another 4,000 were at risk in Chivi and Masvingo districts after levels at Tokwe-Mukorsi dam rose The CPC is appealing for assistance in the form of food, tents, blankets, rapidly, threatening communities within the dam basin. buckets, clothing, medication and fuel in order to assist the a!ected families. -

COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT in RESILIENCE BUILDING PROJECTS: CASE of CHIREDZI and MWENEZI DISTRICT of ZIMBABWE MUTAMBARA, Solomon

COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT IN RESILIENCE BUILDING PROJECTS: CASE OF CHIREDZI AND MWENEZI DISTRICT OF ZIMBABWE MUTAMBARA, Solomon Livelihoods Analyst 1791 Mkoba 14 Gweru, Zimbabwe Email address: [email protected] And BODZO Eugenia Independent Researcher 6922B, Western Triangle Highfield, Harare, Zimbabwe Email address: [email protected] Abstract The aim of this article is to show how collaborative management is important and how it has been embraced in the implementation of resilience building interventions in rural communities. It seeks to unravel the empirical implications of collaborative management and how it has been used in a resilience building project (Enhancing Community Resilience and Sustainability (ECRAS). The recent increased interest amongst development agencies in working with the private sector, and the general increase in the number of multi-stakeholder partnerships is a response to dissatisfaction with the scale, scope and speed of poverty reduction efforts. The complexity and multi-dimensionality of rural poverty calls for an integrated, holistic, sustainable multi-sectorial and collaborative development approach in resilience building. Experiences from the ECRAS project show that effective collaboration across multiple actors should be cascaded to those responsible for actual field implementation. Collaborative management saw the project promoting functional networks among diverse stakeholders through innovation platform, community dialogues, WhatsApp platforms, gender dialogues, participatory scenario planning, community score card, meetings at different levels and all cluster meetings. The process required the project management team to exude adaptive management strategies facilitating decentralised management responsibilities and making extensive use of localized control loops. It also involved smart pooling together of multiple stakeholders from different sectors - with different expertise, skills, resources, powers and interest. -

Livestock in Food Security International Development – and to the Mandate of FAO - This Report Tells the Story of Livestock and Food Security from Three Perspectives

World Livestock 2011 Although much has been said about livestock’s role in achieving food security, World Livestock 2011 in reality, the subject has been only partially addressed and no current document fully covers the topic. Recognizing that food security is central to Livestock in food security international development – and to the mandate of FAO - this report tells the story of livestock and food security from three perspectives. It begins by presenting a global overview, examining the role that livestock play in Livestock in food security human nutrition, the world food supply and access to food particularly for poor families. Next it moves from the global level to a human perspective, examining the way in which livestock contributes to the food security of three different human populations –livestock-dependent societies, small-scale mixed farmers and urban dwellers. The final part of the report looks to the future. It discusses the expected demand for livestock source food and the way that increased demand can be met with ever more limited resources. It reviews the drivers that led to the livestock revolution, how these have changed and what the implications will be for livestock contributing to resilient food systems of the future. World Livestock 2011 Livestock in food security FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2011 CONTRIBUTORS Editor: A. McLeod Copy editing: N. Hart Design: C. Ciarlantini The following people contributed to the content of this document: V. Ahuja, C. Brinkley, S. Gerosa, B. Henderson, N. Honhold, S. Jutzi, F. Kramer, H. Makkar, A. McLeod, H. Miers, E. Muehlhoff, C. -

Policy Brief No

Policy Brief No. 2014 02, Zimbabwean context, one witnesses an interesting mixture of international investors, politicians and rich white businesses coming together to acquire large tracts of land. The study focuses on Nuanetsi Range in National and International Mwenezi and bio-fuel plant in Chisumbanje. Showing how communities with different Actors in the Orchestration of claims to land have been affected by land Large-scale Land Deals in acquisitions, it questions the historical evolution of contested lands in both areas. Zimbabwe: What’s in It for What is interesting is to highlight how Smallholder Farmers? government, local elites and investors use legal systems to justify denying people’s access to land. Manase Kudzai Chiweshe and Study Areas Patience Mutopo Nuanetsi Ranch is located in Mwenezi East in the Southern part of Zimbabwe, in Masvingo Province. It is located 3 kms from the Chirundu-Beitbridge R1 highway which Organisation for Social Science connects Zambia, Zimbabwe and South Researh in Eastern and Southern Africa. It is approximately 500 metres from Africa (OSSREA) the Mwenezi Rural District Council, were the offices of the district administrator, environmental management agency, the Ministry of constitutional affairs and the Introduction district agricultural extension are located. Nuanetsi is located in Ward Thirteen. It ittle research has been done on covers more than 376,995 hectares of land the possible benefits of large- (Mwenezi district files, February 2010), scale land deals for local which constitute more than 1% of communities. This work builds Zimbabwe’s total land area. on a recent study that seeks to outline the potential benefits of land deals in Chisumbanje is a village in the province L of Manicaland, Zimbabwe.