Masvingo Province

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020

Statutory Instrument 55 ofS.I. 2020. 55 of 2020 Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) [CAP. 23:02 Order, 2020 (No. 20) Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) “THIRTEENTH SCHEDULE Order, 2020 (No. 20) CUSTOMS DRY PORTS IT is hereby notifi ed that the Minister of Finance and Economic (a) Masvingo; Development has, in terms of sections 14 and 236 of the Customs (b) Bulawayo; and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02], made the following notice:— (c) Makuti; and 1. This notice may be cited as the Customs and Excise (Ports (d) Mutare. of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020 (No. 20). 2. Part I (Ports of Entry) of the Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) Order, 2002, published in Statutory Instrument 14 of 2002, hereinafter called the Order, is amended as follows— (a) by the insertion of a new section 9A after section 9 to read as follows: “Customs dry ports 9A. (1) Customs dry ports are appointed at the places indicated in the Thirteenth Schedule for the collection of revenue, the report and clearance of goods imported or exported and matters incidental thereto and the general administration of the provisions of the Act. (2) The customs dry ports set up in terms of subsection (1) are also appointed as places where the Commissioner may establish bonded warehouses for the housing of uncleared goods. The bonded warehouses may be operated by persons authorised by the Commissioner in terms of the Act, and may store and also sell the bonded goods to the general public subject to the purchasers of the said goods paying the duty due and payable on the goods. -

Mozambique Zambia South Africa Zimbabwe Tanzania

UNITED NATIONS MOZAMBIQUE Geospatial 30°E 35°E 40°E L a k UNITED REPUBLIC OF 10°S e 10°S Chinsali M a l a w TANZANIA Palma i Mocimboa da Praia R ovuma Mueda ^! Lua Mecula pu la ZAMBIA L a Quissanga k e NIASSA N Metangula y CABO DELGADO a Chiconono DEM. REP. OF s a Ancuabe Pemba THE CONGO Lichinga Montepuez Marrupa Chipata MALAWI Maúa Lilongwe Namuno Namapa a ^! gw n Mandimba Memba a io u Vila úr L L Mecubúri Nacala Kabwe Gamito Cuamba Vila Ribáué MecontaMonapo Mossuril Fingoè FurancungoCoutinho ^! Nampula 15°S Vila ^! 15°S Lago de NAMPULA TETE Junqueiro ^! Lusaka ZumboCahora Bassa Murrupula Mogincual K Nametil o afu ezi Namarrói Erego e b Mágoè Tete GiléL am i Z Moatize Milange g Angoche Lugela o Z n l a h m a bez e i ZAMBEZIA Vila n azoe Changara da Moma n M a Lake Chemba Morrumbala Maganja Bindura Guro h Kariba Pebane C Namacurra e Chinhoyi Harare Vila Quelimane u ^! Fontes iq Marondera Mopeia Marromeu b am Inhaminga Velha oz P M úngu Chinde Be ni n è SOFALA t of ManicaChimoio o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o gh ZIMBABWE o Bi Mutare Sussundenga Dondo Gweru Masvingo Beira I NDI A N Bulawayo Chibabava 20°S 20°S Espungabera Nova OCE A N Mambone Gwanda MANICA e Sav Inhassôro Vilanculos Chicualacuala Mabote Mapai INHAMBANE Lim Massinga p o p GAZA o Morrumbene Homoíne Massingir Panda ^! National capital SOUTH Inhambane Administrative capital Polokwane Guijá Inharrime Town, village o Chibuto Major airport Magude MaciaManjacazeQuissico International boundary AFRICA Administrative boundary MAPUTO Xai-Xai 25°S Nelspruit Main road 25°S Moamba Manhiça Railway Pretoria MatolaMaputo ^! ^! 0 100 200km Mbabane^!Namaacha Boane 0 50 100mi !\ Bela Johannesburg Lobamba Vista ESWATINI Map No. -

Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital

Province District Name of Site Bulawayo Bulawayo City E. F. Watson Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital Bulawayo Bulawayo City Nkulumane Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City United Bulawayo Hospital Manicaland Buhera Birchenough Bridge Hospital Manicaland Buhera Murambinda Mission Hospital Manicaland Chipinge Chipinge District Hospital Manicaland Makoni Rusape District Hospital Manicaland Mutare Mutare Provincial Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Bonda Mission Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Hauna District Hospital Harare Chitungwiza Chitungwiza Central Hospital Harare Chitungwiza CITIMED Clinic Masvingo Chiredzi Chikombedzi Mission Hospital Masvingo Chiredzi Chiredzi District Hospital Masvingo Chivi Chivi District Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chimombe Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chinyika Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chitando Rural Health Centre Masvingo Gutu Gutu Mission Hospital Masvingo Gutu Gutu Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Mukaro Mission Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Masvingo Provincial Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Morgenster Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Matibi Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Neshuro District Hospital Masvingo Zaka Musiso Mission Hospital Masvingo Zaka Ndanga District Hospital Matabeleland South Beitbridge Beitbridge District Hospital Matabeleland South Gwanda Gwanda Provincial Hospital Matabeleland South Insiza Filabusi District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe Plumtree District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe St Annes Mission Hospital (Brunapeg) Matabeleland South Matobo Maphisa District Hospital Matabeleland South Umzingwane Esigodini District Hospital Midlands Gokwe South Gokwe South District Hospital Midlands Gweru Gweru Provincial Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Kwekwe General Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Silobela District Hospital Midlands Mberengwa Mberengwa District Hospital . -

Government Gazette I';

5 ■ I K Sisks'! LA. COUNTV !' NOV-6 1996 i i '{MlmM / ZIMBABWEAN 3 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE I';, Published by Authority I, Vol. LXXIV, No. 52 4th OCTOBER, 1996 Price. $3,00 General Notice 511 of 1996. Tender number GOVERNMENT TENDER BOARD ZRP/TS/I /96. Supply and delivery of workshop consumables; Clos ! ing date, 24.10.96. Tender documents for tender ZRP/TS/1/ Tenders Invited 96 are obtainable from the Zimbabwe Republic Police, Transport Buyer, Tomlison Depot, Transport Stores. Tele All lenders must be submitted to the Secretary, Government Tender Board, P.O. Box phone; 735756 Ext. 2043, Harare. CY 408, Causeway. ''ET.7/96. Supply and delivery of vaccines to Department of Veteri Tenders must in no circumstances be submitted to departments. nary Services for the period 1st January, 1997 to 31st Tenders must be enclosed in sealed envelopes, endorsed on the outside with the September, 1997. Closing date, 24.10.96. Tender documents ^vertised lender number, description, closing date and must be posted in time to be for tender VET.7/96 are obtainable from the Director of sorted into Post Office Box CY 408, Causeway, or delivered by hand to the Secretary, Veterinary Services, First Floor, Ngunguoyana Building, Government Tender Board, Fourth Floor, Atlas House, 62. Robert Mugabe Road, Number 1, Borrowdale Road, Harare. , Harare, before 10 a.m. on the closing date notified. Tenders are invited from registered building contractors in J Offers submitted by telegraph, stating clearly therein the name of the tenderer, the Category “D" service and the amount must be dispatched in time for deliveiy by the Post Office to the CON.20/96. -

Promotion of Climate-Resilient Lifestyles Among Rural Families in Gutu

Promotion of climate-resilient lifestyles among rural families in Gutu (Masvingo Province), Mutasa (Manicaland Province) and Shamva (Mashonaland Central Province) Districts | Zimbabwe Sahara and Sahel Observatory 26 November 2019 Promotion of climate-resilient lifestyles among rural families in Gutu Project/Programme title: (Masvingo Province), Mutasa (Manicaland Province) and Shamva (Mashonaland Central Province) Districts Country(ies): Zimbabwe National Designated Climate Change Management Department, Ministry of Authority(ies) (NDA): Environment, Water and Climate Development Aid from People to People in Zimbabwe (DAPP Executing Entities: Zimbabwe) Accredited Entity(ies) (AE): Sahara and Sahel Observatory Date of first submission/ 7/19/2019 V.1 version number: Date of current submission/ 11/26/2019 V.2 version number A. Project / Programme Information (max. 1 page) ☒ Project ☒ Public sector A.2. Public or A.1. Project or programme A.3 RFP Not applicable private sector ☐ Programme ☐ Private sector Mitigation: Reduced emissions from: ☐ Energy access and power generation: 0% ☐ Low emission transport: 0% ☐ Buildings, cities and industries and appliances: 0% A.4. Indicate the result ☒ Forestry and land use: 25% areas for the project/programme Adaptation: Increased resilience of: ☒ Most vulnerable people and communities: 25% ☒ Health and well-being, and food and water security: 25% ☐ Infrastructure and built environment: 0% ☒ Ecosystem and ecosystem services: 25% A.5.1. Estimated mitigation impact 399,223 tCO2eq (tCO2eq over project lifespan) A.5.2. Estimated adaptation impact 12,000 direct beneficiaries (number of direct beneficiaries) A.5. Impact potential A.5.3. Estimated adaptation impact 40,000 indirect beneficiaries (number of indirect beneficiaries) A.5.4. Estimated adaptation impact 0.28% of the country’s total population (% of total population) A.6. -

1 Research Application Summary Evaluating the Level of Adoption Of

Research Application Summary Evaluating the level of adoption of improved agrosilvopastoral technologies, factors affecting adoption and establishing the species and systems adopted among small holder farmers of Buhera and Mutasa Districts of Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe Chihota B.P., Mupanda K., Mrema M., Tagwira F. & Ajayi O.C. Background Two thirds of the rural populations in most countries of Sub-Saharan Africa subsist on less than US$1 a day. The farmers’ economies have weak linkages to the markets and they have little or no access to external inputs. The increasing cost of inputs and high transport costs make external inputs unaffordable for the smallholder farmer (Spencer, 2002). Inorganic fertilizer use has declined to 8kg/ha (NEPAD, 2006). Smallholder farmers cannot afford stock feeds for supplementing limited and poor quality pasture during the dry and cold season. Land degradation and siltation are an environmental concern that also reduces yields (Rattsø, 1996). Crop and livestock yields are low and declining. Countries like Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique and Botswana are affected and as a result, food insecure (Bohringer, 2002). Some agroforestry technologies have been shown to improve the soil and animal fodder availability (Dzowela, 1994; Govere, 2003). Agroforestry can improve crop and livestock production by providing relatively less costly, more affordable and locally available inputs for fodder and soil amendments to the smallholder farmer. Government departments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like World Agroforestry Centre (WAC) are scaling up agroforestry through training and distributing germplasm to the smallholder farmers in the region. Not much has been done on assessment of adoption and factors that affect adoption of agroforestry in different geographical areas and agricultural sectors in Zimbabwe. -

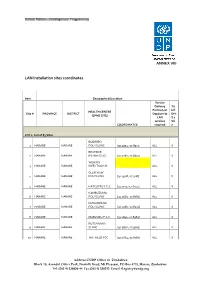

LAN Installation Sites Coordinates

ANNEX VIII LAN Installation sites coordinates Item Geographical/Location Service Delivery Tic Points (List k if HEALTH CENTRE Site # PROVINCE DISTRICT Dept/umits DHI (EPMS SITE) LAN S 2 services Sit COORDINATES required e LOT 1: List of 83 Sites BUDIRIRO 1 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9354,-17.8912] ALL X BEATRICE 2 HARARE HARARE RD.INFECTIO [31.0282,-17.8601] ALL X WILKINS 3 HARARE HARARE INFECTIOUS H ALL X GLEN VIEW 4 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9508,-17.908] ALL X 5 HARARE HARARE HATCLIFFE P.C.C. [31.1075,-17.6974] ALL X KAMBUZUMA 6 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9683,-17.8581] ALL X KUWADZANA 7 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9285,-17.8323] ALL X 8 HARARE HARARE MABVUKU P.C.C. [31.1841,-17.8389] ALL X RUTSANANA 9 HARARE HARARE CLINIC [30.9861,-17.9065] ALL X 10 HARARE HARARE HATFIELD PCC [31.0864,-17.8787] ALL X Address UNDP Office in Zimbabwe Block 10, Arundel Office Park, Norfolk Road, Mt Pleasant, PO Box 4775, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: (263 4) 338836-44 Fax:(263 4) 338292 Email: [email protected] NEWLANDS 11 HARARE HARARE CLINIC ALL X SEKE SOUTH 12 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0763,-18.0314] ALL X SEKE NORTH 13 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0943,-18.0152] ALL X 14 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ST.MARYS CLINIC [31.0427,-17.9947] ALL X 15 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ZENGEZA CLINIC [31.0582,-18.0066] ALL X CHITUNGWIZA CENTRAL 16 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA HOSPITAL [31.0628,-18.0176] ALL X HARARE CENTRAL 17 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [31.0128,-17.8609] ALL X PARIRENYATWA CENTRAL 18 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [30.0433,-17.8122] ALL X MURAMBINDA [31.65555953980,- 19 MANICALAND -

The Policy and Legislative Framework for Zimbabwe's Fast Track Land Reform Programme and Its Implications on Women's Rights

The Policy and Legislative Framework for Zimbabwe’s Fast Track Land Reform Programme and its Implications on Women’s Rights to Agricultural Land BY MAKANATSA MAKONESE Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Law Southern and East African Regional Centre for Women’s Law (SEARCWL) University of Zimbabwe Supervisors Professor Julie Stewart and Professor Anne Hellum 2017 i Dedication To my two mothers, Betty Takaidza Nhengu (Gogo Dovi) and Felistas Dzidzai Nhengu (Gogo Banana) - Because of you, I believe in love. To my late brothers Thompson, Thomas Hokoyo and Munyenyiwa Nhengu; I know you would have been so proud of this accomplishment. To my late father, VaMusarinya, In everything I do, I always remember that “ndiri mwana wa Ticha Nhengu” ii Acknowledgments For any work of this magnitude, there are always so many people who contribute in many but unique ways in making the assignment possible. If I were to mention all the people that played a part in small and big ways in making this dream a reality, it would be such a long list. To all of you, I say, thank you. I am grateful to my supervisors, Professor Julie Stewart and Professor Anne Hellum for your guidance, patience, commitment, for the occasional “wake-up” slap and for meticulously combing through the many chapters and versions of this thesis which I produced along the way. Thank you for believing in me and for assuring me that with hard work, I could do it. I would also like to thank Professor William Derman of the Norwegian University of Life Sciences for his advice on my thesis and for providing me with volumes of useful reading material on the Zimbabwean land question. -

Inter-Agency Flooding Rapid Assessment Report 18-19 March

Inter-Agency Flooding Rapid Assessment Report 18-19 March - 2019 Supported by the Department of Civil Protection, UN-Agencies and NGOs Page | 1 Table of Contents Page | 2 1.0 General Assessment Information Main Objective of the assessment The main purpose of the Inter-Agency rapid assessment was to ascertain the scale and scope of the flooding situation focusing on key areas/sectors namely shelter and non-food items, Health and nutrition, Food security, WASH, Environment, Education, Protection and Early Recovery, its impact on individuals, communities, institutions and refugees. Specific Objectives of the Assessment • To determine the number of the affected people and establish their demographic characteristics • To determine the immediate, intermediate and long term needs of the affected communities Methodology • Field visits in accessible affected areas in Chimanimani and Chipinge; • Key informant interviews with the Provincial and District Administrators (Face to face and tele- interviews); • Secondary analysis of sectoral reports; • Key informant interviews with affected people. 1.1 Background of the flooding Zimbabwe experienced torrential rainfall caused by Cyclone Idai from the 15th of March 2019 to the 17th of March 2019.Tropical Cyclone Idai which was downgraded to a tropical depression on the 16th of March 2019 caused high winds and heavy precipitation in Chimanimani, Chipinge, Buhera, Nyanga, Makoni, Mutare Rural, Mutasa and parts of Mutare Urban Chimanimani and Chipinge districts among other districts, causing riverine and flash flooding and subsequent deaths, destruction of livelihoods and properties. To date, Chimanimani district is the most affected. An estimated 50,000 households/250,000 people were affected by flooding and landslides in Chimanimani and Chipinge, when local rivers and their tributaries burst their banks and caused the inundation of homes and schools causing considerable damage to property and livelihoods and in some cases deaths. -

Gonarezhou National Park (GNP) and the Indigenous Communities of South East Zimbabwe, 1934-2008

Living on the fringes of a protected area: Gonarezhou National Park (GNP) and the indigenous communities of South East Zimbabwe, 1934-2008 by Baxter Tavuyanago A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the Department of Historical and Heritage Studies at the UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR A. S. MLAMBO July 2016 i © University of Pretoria Abstract This study examines the responses of communities of south-eastern Zimbabwe to their eviction from the Gonarezhou National Park (GNP) and their forced settlement in the peripheral areas of the park. The thesis establishes that prior to their eviction, the people had created a utilitarian relationship with their fauna and flora which allowed responsible reaping of the forest’s products. It reveals that the introduction of a people-out conservation mantra forced the affected communities to become poachers, to emigrate from south-eastern Zimbabwe in large numbers to South Africa for greener pastures and, to fervently join militant politics of the 1960s and 1970s. These forms of protests put them at loggerheads with the colonial government. The study reveals that the independence government’s position on the inviolability of the country’s parks put the people and state on yet another level of confrontation as the communities had anticipated the restitution of their ancestral lands. The new government’s attempt to buy their favours by engaging them in a joint wildlife management project called CAMPFIRE only slightly relieved the pain. The land reform programme of the early 2000s, again, enabled them to recover a small part of their old Gonarezhou homeland. -

Zimbabwe Rural Electrification Study

Zimbabwe Rural Electrification Study ESM228 Energy Sector Management Assistance Programme Report 228/00 EJol AD March 2000 JOINT UNDP / WORLD BANK ENERGY SECTOR MANAGEMENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAMME (ESMAP) PURPOSE The Joint UNDP/World Bank E nergy Sector Management Assistance Programme (ESMAP) is a special global technical assistance program run as part of the World Bank's Energy, Mining and Telecommunications Department. ESMAP provides advice to governments on sustainable energy development. Established with the support of UNDP and bilateral official donors in 1983, it focuses on the role of energy in the development process with the objective of contributing to poverty alleviation, improving living conditions and preserving the environment in developing countries and transition economies. ESMAP centers its interventions on three priority areas: sector reform and restructuring; access to modern energy for the poorest; and promotion of sustainable energy practices. GOVERNANCE AND OPERATIONS ESMAP is governed by a Consultative Group (ESMAP CG) composed of representatives of the UNDP and World Bank, other donors, and development experts from regions benefiting from ESMAP's assistance. The ESMAP CG is chaired by a World Bank Vice President, and advised by a Technical Advisory Group (TAG) of four independent energy experts that reviews the Programme's strategic agenda, its work plan, and its achievements. ESMAP relies on a cadre of engineers, energy planners, and economists from the World Bank to conduct its activities under the guidance of the -

Zimbabwe Market Study: Masvingo Province Report

©REUTERS/Philimon Bulawayo Bulawayo ©REUTERS/Philimon R E S E A R C H T E C H N I C A L A S S I S T A N C E C E N T E R January 2020 Zimbabwe Market Study: Masvingo Province Report Dominica Chingarande, Gift Mugano, Godfrey Chagwiza, Mabel Hungwe Acknowledgments The Research team expresses its gratitude to the various stakeholders who participated in this study in different capacities. Special gratitude goes to the District Food and Nutrition Committee members, the District Drought Relief Committee members, and various market actors in the province for providing invaluable local market information. We further express our gratitude to the ENSURE team in Masvingo for mobilizing beneficiaries of food assistance who in turn shared their lived experiences with food assistance. To these food assistance beneficiaries, we say thank you for freely sharing your experiences. Research Technical Assistance Center The Research Technical Assistance Center is a world-class research consortium of higher education institutions, generating rapid research for USAID to promote evidence-based policies and programs. The project is led by NORC at the University of Chicago in partnership with Arizona State University, Centro de Investigacin de la Universidad del Pacifico (Lima, Peru), Davis Management Group, the DevLab@Duke University, Forum One, the Institute of International Education, the Notre Dame Initiative for Global Development, Population Reference Bureau, the Resilient Africa Network at Makerere University (Kampala, Uganda), the United Negro College Fund, the University of Chicago, and the University of Illinois at Chicago. The Research Technical Assistance Center (RTAC) is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of contract no.