How African Art Influenced Pablo Picasso and His Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artists' Journeys IMAGE NINE: Paul Gauguin. French, 1848–1903. Noa

LESSON THREE: Artists’ Journeys 19 L E S S O N S IMAGE NINE: Paul Gauguin. French, 1848–1903. IMAGE TEN: Henri Matisse. French, Noa Noa (Fragrance) from Noa Noa. 1893–94. 1869–1954. Study for “Luxe, calme et volupté.” 7 One from a series of ten woodcuts. Woodcut on 1905. Oil on canvas, 12 ⁄8 x 16" (32.7 x endgrain boxwood, printed in color with stencils. 40.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, 1 Composition: 14 x 8 ⁄16" (35.5 x 20.5 cm); sheet: New York. Mrs. John Hay Whitney Bequest. 1 5 15 ⁄2 x 9 ⁄8" (39.3 x 24.4 cm). Publisher: the artist, © 2005 Succession H. Matisse, Paris/Artists Paris. Printer: Louis Ray, Paris. Edition: 25–30. Rights Society (ARS), New York The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Lillie P. Bliss Collection IMAGE ELEVEN: Henri Matisse. French, 1869–1954. IMAGE TWELVE: Vasily Kandinsky. French, born Landscape at Collioure. 1905. Oil on canvas, Russia, 1866–1944. Picture with an Archer. 1909. 1 3 7 3 15 ⁄4 x 18 ⁄8" (38.8 x 46.6 cm). The Museum of Oil on canvas, 68 ⁄8 x 57 ⁄8" (175 x 144.6 cm). Modern Art, New York. Gift and Bequest of Louise The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift and Reinhardt Smith. © 2005 Succession H. Matisse, Bequest of Louise Reinhardt Smith. © 2005 Artists Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP,Paris INTRODUCTION Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists often took advantage of innovations in transportation by traveling to exotic or rural locations. -

In a Splendid Exhibition, the École Des Beaux- Arts in Paris Is Currently

Ausstellungsbericht 22.12.2008 Exhibition Review Editor: R. Donandt Exhibition: Figures du corps. Une leçon d'anatomie aux beaux-arts. Paris, École natio- nale supérieure des beaux-arts, Paris. 21.10.2008-04.01.2009 Exhibition catalogue: Philippe Comar (ed.): Figures du corps. Une leçon d'anatomie aux beaux-arts. Beaux-arts de Paris les editions, 2008. 509 p., 800 ill. ISBN: 978-2-84056-269- 6. 45,- EUR. Mechthild Fend, University College London In a splendid exhibition, the École des beaux- sixteenth-century displays include the well arts in Paris is currently showing their own known anatomical treatises by Vesalius and anatomical collections enriched by a small Estienne, studies on proportion after Vitruvius number of objects from other French institu- and by Lomazzo and Dürer, as well as écorchés tions. Usually behind the scenes - stored away and muscle studies by Bandinelli or Antonio del in archives and galleries reserved for the train- Pollaiuolo. In the next of the six sections, which ing of art students - the books, prints, draw- are organized more or less in chronological or- ings, photographs, waxmodels or casts are der, the formation of the French art academy up now centre stage in two large exhibition halls until the early nineteenth century is addressed, at Quai Malaquais. With these materials the especially the increasing specialisation of anat- exhibition traces the history of anatomy train- omy training for artists; this development is also ing at the French national art school. The pres- explored in the catalogue essay by Morwena tigious institution was founded in 1648 under Joly. -

Henri Matisse's the Italian Woman, by Pierre

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-to-Reel collection Hilla Rebay Lecture: Henri Matisse’s The Italian Woman, by Pierre Schneider, 1982 PART 1 THOMAS M. MESSER Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the third lecture within the Hilla Rebay Series. As you know, it is dedicated to a particular work of art, and so I must remind you that last spring, the Museum of Modern Art here in New York, and the Guggenheim, engaged in something that I think may be called, without exaggeration, a historic exchange of masterpieces. We agreed to complete MoMA’s Kandinsky seasons, because the Campbell panels that I ultimately perceived as seasons, had, [00:01:00] until that time, been divided between the Museum of Modern Art and ourselves. We gave them, in other words, fall and winter, to complete the foursome. In exchange, we received, from the Museum of Modern Art, two very important paintings: a major Picasso Still Life of the early 1930s, and the first Matisse ever to enter our collection, entitled The Italian Woman. The public occasion has passed. We have, for the purpose, reinstalled the entire Thannhauser wing, and I'm sure that you have had occasion to see how the Matisse and the new Picasso have been included [00:02:00] in our collection. It seemed appropriate to accompany this public gesture with a scholarly event, and we have therefore, decided this year, to devote the Hilla Rebay Lecture to The Italian Woman. Naturally, we had to find an appropriate speaker for the event and it did not take us too long to come upon Pierre Schneider, who resides in Paris and who has agreed to make his very considerable Matisse expertise available for this occasion. -

Russian Art+ Culture

RUSSIAN ART+ CULTURE WINTER GUIDE RUSSIAN ART WEEK, LONDON 23-30 NOVEMBER 2018 Russian Art Week Guide, oktober 2018 CONTENTS Russian Sale Icons, Fine Art and Antiques AUCTION IN COPENHAGEN PREVIEW IN LONDON FRIDAY 30 NOVEMBER AT 2 PM Shapero Modern 32 St George Street London W1S 2EA 24 november: 2 pm - 6 pm 25 november: 11 am - 5 pm 26 november: 9 am - 6 pm THIS ISSUE WELCOME RUSSIAN WORKS ON PAPER By Natasha Butterwick ..................................3 1920’s-1930’s ............................................. 12 AUCTION HIGHLIGHTS FEATURED EVENTS ...........................14 By Simon Hewitt ............................................ 4 RUSSIAN TREASURES IN THE AUCTION SALES ROYAL COLLECTION Christie's, Sotheby's ........................................8 Interview with Caroline de Guitaut ............... 24 For more information please contact MacDougall's, Bonhams .................................9 Martin Hans Borg on +45 8818 1128 Bruun Rasmussen, Roseberys ........................10 RA+C RECOMMENDS .....................30 or [email protected] Stockholms Auktionsverk ................................11 PARTNERS ...............................................32 Above: Georgy Rublev, Anti-capitalist picture "Demonstration", 1932. Tempera on paper, 30 x 38 cm COPENHAGEN, DENMARK TEL +45 8818 1111 Cover: Laurits Regner Tuxen, The Marriage of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia, 26th November 1894, 1896 BRUUN-RASMUSSEN.COM Credit: Royal Collection Trust/ © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018 russian art week guide_1018_150x180_engelsk.indd 1 11/10/2018 14.02 INTRODUCTION WELCOME Russian Art Week, yet again, strong collection of 19th century Russian provides the necessary Art featuring first-class work by Makovsky cultural bridge between and Pokhitonov, whilst MacDougall's, who Russia and the West at a time continue to provide our organisation with of even worsening relations fantastic support, have a large array of between the two. -

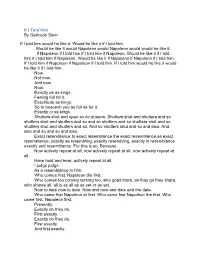

If I Told Him Stein + Picasso

If I Told Him By Gertrude Stein If I told him would he like it. Would he like it if I told him. Would he like it would Napoleon would Napoleon would would he like it. If Napoleon if I told him if I told him if Napoleon. Would he like it if I told him if I told him if Napoleon. Would he like it if Napoleon if Napoleon if I told him. If I told him if Napoleon if Napoleon if I told him. If I told him would he like it would he like it if I told him. Now. Not now. And now. Now. Exactly as as kings. Feeling full for it. Exactitude as kings. So to beseech you as full as for it. Exactly or as kings. Shutters shut and open so do queens. Shutters shut and shutters and so shutters shut and shutters and so and so shutters and so shutters shut and so shutters shut and shutters and so. And so shutters shut and so and also. And also and so and so and also. Exact resemblance to exact resemblance the exact resemblance as exact resemblance, exactly as resembling, exactly resembling, exactly in resemblance exactly and resemblance. For this is so. Because. Now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all. Have hold and hear, actively repeat at all. I judge judge. As a resemblance to him. Who comes first. Napoleon the first. Who comes too coming coming too, who goes there, as they go they share, who shares all, all is as all as as yet or as yet. -

Russian Avant-Garde, 1904-1946 Books and Periodicals

Russian Avant-garde, 1904-1946 Books and Periodicals Most comprehensive collection of Russian Literary Avant-garde All groups and schools of the Russian Literary Avant-garde Fascinating books written by famous Russian authors Illustrations by famous Russian artists (Malevich, Goncharova, Lisitskii) Extremely rare, handwritten (rukopisnye) books Low print runs, published in the Russian provinces and abroad Title list available at: www.idc.nl/avantgarde National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg Editor: A. Krusanov Russian Avant-garde, 1904-1946 This collection represents works of all Russian literary avant-garde schools. It comprises almost 800 books, periodicals and almanacs most of them published between 1910-1940, and thus offers an exceptionally varied and well-balanced overview of one of the most versatile movements in Russian literature. The books in this collection can be regarded as objects of art, illustrated by famous artists such as Malevich, Goncharova and Lisitskii. This collection will appeal to literary historians and Slavists, as well as to book and art historians. Gold mine Khlebnikov, Igor Severianin, Sergei Esenin, Anatolii Mariengof, Ilia Current market value of Russian The Russian literary avant-garde was Avant-garde books both a cradle for many new literary styles Selvinskii, Vladimir Shershenevich, David and Nikolai Burliuk, Alexei Most books in this collection cost and the birthplace of a new physical thousands Dollars per book at the appearance for printed materials. The Kruchenykh, and Vasilii Kamenskii. However, -

Matisse Dance with Joy Ebook

MATISSE DANCE WITH JOY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Susan Goldman Rubin | 26 pages | 03 Jun 2008 | CHRONICLE BOOKS | 9780811862882 | English | San Francisco, United States Matisse Dance with Joy PDF Book Sell your art. Indeed, Matisse, with its use of strong colors and long, curved lines will initially influenced his acolytes Derain and Vlaminck, then expressionist and surrealist painters same. Jun 13, Mir rated it liked it Shelves: art. He starts using this practice since the title, 'Tonight at Noon' as it is impossible because noon can't ever be at night as it is during midday. Tags: h mastisse, matisse henri, matisse joy of life, matisse goldfish, matisse for kids, matisse drawing, drawings, artsy, matisse painting, henri matisse paintings, masterpiece, artist, abstract, matisse, famous, popular, vintage, expensive, henri matisse, womens, matisse artwork. Welcome back. Master's or higher degree. Matisse had a daughter with his model Caroline Joblau in and in he married Amelie Noelie Parayre with whom he raised Marguerite and their own two sons. Henri Matisse — La joie de vivre Essay. Tags: matisse, matisse henri, matisse art, matisse paintings, picasso, picasso matisse, matisse painting, henri matisse art, artist matisse, henri matisse, la danse, matisse blue, monet, mattise, matisse cut outs, matisse woman, van gogh, matisse moma, moma, henry matisse, matisse artwork, mattisse, henri matisse painting, matisse nude, matisse goldfish, dance, the dance, le bonheur de vivre, joy of life, the joy of life, matisse joy of life, bonheur de vivre, the joy of life matisse. When political protest is read as epidemic madness, religious ecstasy as nervous disease, and angular dance moves as dark and uncouth, the 'disorder' being described is choreomania. -

“The First Futurist Manifesto Revisited,” Rett Kopi: Manifesto Issue: Dokumenterer Fremtiden (2007): 152- 56. Marjorie Perl

“The First Futurist Manifesto Revisited,” Rett Kopi: Manifesto issue: Dokumenterer Fremtiden (2007): 152- 56. Marjorie Perloff Almost a century has passed since the publication, in the Paris Figaro on 20 February 1909, of a front-page article by F. T. Marinetti called “Le Futurisme” which came to be known as the First Futurist Manifesto [Figure 1]. Famous though this manifesto quickly became, it was just as quickly reviled as a document that endorsed violence, unbridled technology, and war itself as the “hygiene of the people.” Nevertheless, the 1909 manifesto remains the touchstone of what its author called l’arte di far manifesti (“the art of making manifestos”), an art whose recipe—“violence and precision,” “the precise accusation and the well-defined insult”—became the impetus for all later manifesto-art.1 The publication of Günter Berghaus’s comprehensive new edition of Marinetti’s Critical Writings2 affords an excellent opportunity to reconsider the context as well as the rhetoric of Marinetti’s astonishing document. Consider, for starters, that the appearance of the manifesto, originally called Elettricismo or Dinamismo—Marinetti evidently hit on the more general title Futurismo while making revisions in December 2008-- was delayed by an unforeseen event that took place at the turn of 1909. On January 2, 200,000 people were killed in an earthquake in Sicily. As Berghaus tells us, Marinetti realized that this was hardly an opportune moment for startling the world with a literary manifesto, so he delayed publication until he could be sure he would get front-page coverage for his incendiary appeal to lay waste to cultural traditions and institutions. -

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 18:33 Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Résumé de l'article Volume 21, numéro 2, 2011 Cet article livre des réflexions générales sur quelques défis auxquels les compositeurs africains de musique de concert sont confrontés. Le point de URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar départ spécifique se trouve dans une anthologie qui date de 2009, Piano Music DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar of Africa and the African Diaspora, rassemblée par le pianiste et chercheur ghanéen William Chapman Nyaho et publiée par Oxford University Press. Aller au sommaire du numéro L’anthologie offre une grande panoplie de réalisations artistiques dans un genre qui est moins associé à l’Afrique que la musique « populaire » urbaine ou la musique « traditionnelle » d’origine précoloniale. En notant les avantages méthodologiques d’une approche qui se base sur des compositions Éditeur(s) individuelles plutôt que sur l’ethnographie, l’auteur note l’importance des Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal rencontres de Steve Reich et György Ligeti avec des répertoires africains divers. Puis, se penchant sur un choix de pièces tirées de l’anthologie, l’article rend compte de l’héritage multiple du compositeur africain et la façon dont cet ISSN héritage influence ses choix de sons, rythmes et phraséologie. Des extraits 1183-1693 (imprimé) d’oeuvres de Nketia, Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi et Osman servent d’illustrations à cet 1488-9692 (numérique) article. Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Agawu, K. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Title: Prostitution and Art : Picasso's "Les Demoiselles D'avignon" and the Vicissitudes of Authenticity

Title: Prostitution and art : Picasso's "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" and the vicissitudes of authenticity Author: Sławomir Masłoń Citation style: Masłoń Sławomir. (2020). Prostitution and art : Picasso's "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" and the vicissitudes of authenticity. "Er(r)go" (No. 40, (2020) s. 171-184), doi 10.31261/errgo.7685 Er(r)go. Teoria–Literatura–Kultura Sławomir Masłoń Er(r)go. Theory–Literature–Culture University of Silesia in Katowice Nr / No. 40 (1/2020) pamięć/ideologia/archiwum Faculty of Humanities memory/ideology/archive issn 2544-3186 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5092-6149 https://doi.org/10.31261/errgo.7685 Prostitution and Art Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and the Vicissitudes of Authenticity Abstract: The paper argues against interpretations of Les Demoiselles that look for its meaning in Picasso’s state of mind and treat it as the expression of a struggle with his personal demons. Rather, it interprets both versions of the painting as a response and contrast to Matisse’s Le Bonheur de vivre, which is proposed as the main intertext of Les Demoiselles. Moreover, an excursus into Lacanian theory allows the author not only to explain the supposed inconsistencies of Les Demoiselles , but also to propose that in its final version it is a meta-painting which analyses the way representation comes into being. Keywords: Picasso, gaze, look, authenticity, biographical criticism Nothing seems more like a whorehouse to me than a museum. — Michel Leiris1 In 1906 Picasso is only beginning to make his name in Paris and his painting is far less advanced or “modern” than Matisse’s. -

Fine Art Papers Guide

FINE ART PAPERS GUIDE 100 Series • 200 Series • Vision • 300 Series • 400 Series • 500 Series make something real For over 125 years Strathmore® has been providing artists with the finest papers on which to create their artwork. Our papers are manufactured to exacting specifications for every level of expertise. 100 100 Series | Youth SERIES Ignite a lifelong love of art. Designed for ages 5 and up, the paper types YOUTH and features have been selected to enhance the creative process. Choice of paper is one of the most important 200 Series | Good decisions an artist makes 200SERIES Value without compromise. Good quality paper at a great price that’s economical enough for daily use. The broad range of papers is a great in determining the GOOD starting point for the beginning and developing artist. outcome of their work. Color, absorbency, texture, weight, and ® Vision | Good STRATHMORE size are some of the more important Let the world see your vision. An affordable line of pads featuring extra variables that contribute to different high sheet counts and durable construction. Tear away fly sheets reveal a artistic effects. Whether your choice of vision heavyweight, customizable, blank cover made from high quality, steel blue medium is watercolor, charcoal, pastel, GOOD mixed media paper. Charcoal Paper in our 300, 400 and 500 Series is pencil, or pen and ink, you can be confident that manufactured with a traditional laid finish making we have a paper that will enhance your artistic them the ideal foundation for this medium. The efforts. Our papers are manufactured to exacting laid texture provides a great toothy surface for specifications for every level of expertise.