The Geologic Time Scale 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Change and the Selective Signature of the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction

Climate change and the selective signature of the Late Ordovician mass extinction Seth Finnegana,b,1, Noel A. Heimc, Shanan E. Petersc, and Woodward W. Fischera aDivision of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 91125; bDepartment of Integrative Biology, University of California, 1005 Valley Life Sciences Bldg #3140, Berkeley, CA 94720; and cDepartment of Geoscience, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1215 West Dayton Street, Madison, WI 53706 Edited by Richard K. Bambach, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., and accepted by the Editorial Board March 6, 2012 (received for review October 14, 2011) Selectivity patterns provide insights into the causes of ancient ex- sedimentary record (common cause hypothesis) (14). For the tinction events. The Late Ordovician mass extinction was related LOME, it is useful to split common cause into two hypotheses. to Gondwanan glaciation; however, it is still unclear whether ele- The eustatic common cause hypothesis postulates that Gondwa- vated extinction rates were attributable to record failure, habitat nan glaciation drove the extinction by lowering eustatic sea level, loss, or climatic cooling. We examined Middle Ordovician-Early thereby reducing the overall area of shallow marine habitats, Silurian North American fossil occurrences within a spatiotempo- reorganizing habitat mosaics, and disrupting larval dispersal cor- rally explicit stratigraphic framework that allowed us to quantify ridors (16–18). The climatic common cause hypothesis postulates rock record effects on a per-taxon basis and assay the interplay of that climate cooling, in addition to being ultimately responsible macrostratigraphic and macroecological variables in determining for sea-level drawdown and attendant habitat losses, had a direct extinction risk. -

Diversity Partitioning During the Cambrian Radiation

Diversity partitioning during the Cambrian radiation Lin Naa,1 and Wolfgang Kiesslinga,b aGeoZentrum Nordbayern, Paleobiology and Paleoenvironments, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, 91054 Erlangen, Germany; and bMuseum für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Research on Evolution and Biodiversity at the Humboldt University Berlin, 10115 Berlin, Germany Edited by Douglas H. Erwin, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC, and accepted by the Editorial Board March 10, 2015 (received for review January 2, 2015) The fossil record offers unique insights into the environmental and Results geographic partitioning of biodiversity during global diversifica- Raw gamma diversity exhibits a strong increase in the first three tions. We explored biodiversity patterns during the Cambrian Cambrian stages (informally referred to as early Cambrian in this radiation, the most dramatic radiation in Earth history. We as- work) (Fig. 1A). Gamma diversity dropped in Stage 4 and de- sessed how the overall increase in global diversity was partitioned clined further through the rest of the Cambrian. The pattern is between within-community (alpha) and between-community (beta) robust to sampling standardization (Fig. 1B) and insensitive to components and how beta diversity was partitioned among environ- including or excluding the archaeocyath sponges, which are po- ments and geographic regions. Changes in gamma diversity in the tentially oversplit (16). Alpha and beta diversity increased from Cambrian were chiefly driven by changes in beta diversity. The the Fortunian to Stage 3, and fluctuated erratically through the combined trajectories of alpha and beta diversity during the initial following stages (Fig. 2). Our estimate of alpha (and indirectly diversification suggest low competition and high predation within beta) diversity is based on the number of genera in published communities. -

Sandbian) K-Bentonites in Oslo, Norway T ⁎ Eirik G

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 520 (2019) 203–213 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo A new age model for the Ordovician (Sandbian) K-bentonites in Oslo, Norway T ⁎ Eirik G. Balloa, , Lars Eivind Auglanda, Øyvind Hammerb, Henrik H. Svensena a Centre for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED), University of Oslo, Pb. 1028, 0316 Oslo, Norway b Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, Pb. 1172, 0318 Oslo, Norway ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: During the Late Ordovician, large explosive volcanic eruptions deposited worldwide K-bentonites, including the Chronostratigraphy Millbrig and Deicke K-bentonites in North America and the Kinnekulle K-bentonite in Scandinavia. We have Sandbian-Katian boundary studied a classical locality in Oslo containing one of the most complete sections of K-bentonites in Europe. U-Pb dating In a 53 m section of Sandbian age, we discovered 33 individual K-bentonite beds, the most notable beds being Milankovitch the Kinnekulle and the upper Grimstorp K-bentonite. Magnetic susceptibility (MS) measurements on two in- Age model tervals show significant periodicity peaks interpreted as Milankovitch cycles and thus astronomically forced Kinnekulle changes in sediment supply and composition. These cycles fit remarkably well with both the expected Milankovitch periodicities for the Ordovician as well as the radiometric ages presented in this study and may represent one of the most convincing demonstrations of Milankovitch cycles from the lower Paleozoic so far. Five of the K-bentonites have been dated by high-precision chemical abrasion-thermal ionization mass spectrometry (CA-TIMS) U-Pb zircon geochronology, where the Kinnekulle K-bentonite gives an age of 454.06 ± 0.43 Ma. -

A Community Effort Towards an Improved Geological Time Scale

A community effort towards an improved geological time scale 1 This manuscript is a preprint of a paper that was submitted for publication in Journal 2 of the Geological Society. Please note that the manuscript is now formally accepted 3 for publication in JGS and has the doi number: 4 5 https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2020-222 6 7 The final version of this manuscript will be available via the ‘Peer reviewed Publication 8 DOI’ link on the right-hand side of this webpage. Please feel free to contact any of the 9 authors. We welcome feedback on this community effort to produce a framework for 10 future rock record-based subdivision of the pre-Cryogenian geological timescale. 11 1 A community effort towards an improved geological time scale 12 Towards a new geological time scale: A template for improved rock-based subdivision of 13 pre-Cryogenian time 14 15 Graham A. Shields1*, Robin A. Strachan2, Susannah M. Porter3, Galen P. Halverson4, Francis A. 16 Macdonald3, Kenneth A. Plumb5, Carlos J. de Alvarenga6, Dhiraj M. Banerjee7, Andrey Bekker8, 17 Wouter Bleeker9, Alexander Brasier10, Partha P. Chakraborty7, Alan S. Collins11, Kent Condie12, 18 Kaushik Das13, Evans, D.A.D.14, Richard Ernst15, Anthony E. Fallick16, Hartwig Frimmel17, Reinhardt 19 Fuck6, Paul F. Hoffman18, Balz S. Kamber19, Anton Kuznetsov20, Ross Mitchell21, Daniel G. Poiré22, 20 Simon W. Poulton23, Robert Riding24, Mukund Sharma25, Craig Storey2, Eva Stueeken26, Rosalie 21 Tostevin27, Elizabeth Turner28, Shuhai Xiao29, Shuanhong Zhang30, Ying Zhou1, Maoyan Zhu31 22 23 1Department -

Gondwana Vertebrate Faunas of India: Their Diversity and Intercontinental Relationships

438 Article 438 by Saswati Bandyopadhyay1* and Sanghamitra Ray2 Gondwana Vertebrate Faunas of India: Their Diversity and Intercontinental Relationships 1Geological Studies Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, 203 B. T. Road, Kolkata 700108, India; email: [email protected] 2Department of Geology and Geophysics, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur 721302, India; email: [email protected] *Corresponding author (Received : 23/12/2018; Revised accepted : 11/09/2019) https://doi.org/10.18814/epiiugs/2020/020028 The twelve Gondwanan stratigraphic horizons of many extant lineages, producing highly diverse terrestrial vertebrates India have yielded varied vertebrate fossils. The oldest in the vacant niches created throughout the world due to the end- Permian extinction event. Diapsids diversified rapidly by the Middle fossil record is the Endothiodon-dominated multitaxic Triassic in to many communities of continental tetrapods, whereas Kundaram fauna, which correlates the Kundaram the non-mammalian synapsids became a minor components for the Formation with several other coeval Late Permian remainder of the Mesozoic Era. The Gondwana basins of peninsular horizons of South Africa, Zambia, Tanzania, India (Fig. 1A) aptly exemplify the diverse vertebrate faunas found Mozambique, Malawi, Madagascar and Brazil. The from the Late Palaeozoic and Mesozoic. During the last few decades much emphasis was given on explorations and excavations of Permian-Triassic transition in India is marked by vertebrate fossils in these basins which have yielded many new fossil distinct taxonomic shift and faunal characteristics and vertebrates, significant both in numbers and diversity of genera, and represented by small-sized holdover fauna of the providing information on their taphonomy, taxonomy, phylogeny, Early Triassic Panchet and Kamthi fauna. -

A Template for an Improved Rock-Based Subdivision of the Pre-Cryogenian Timescale

Downloaded from http://jgs.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Perspective Journal of the Geological Society Published Online First https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2020-222 A template for an improved rock-based subdivision of the pre-Cryogenian timescale Graham A. Shields1*, Robin A. Strachan2, Susannah M. Porter3, Galen P. Halverson4, Francis A. Macdonald3, Kenneth A. Plumb5, Carlos J. de Alvarenga6, Dhiraj M. Banerjee7, Andrey Bekker8, Wouter Bleeker9, Alexander Brasier10, Partha P. Chakraborty7, Alan S. Collins11, Kent Condie12, Kaushik Das13, David A. D. Evans14, Richard Ernst15,16, Anthony E. Fallick17, Hartwig Frimmel18, Reinhardt Fuck6, Paul F. Hoffman19,20, Balz S. Kamber21, Anton B. Kuznetsov22, Ross N. Mitchell23, Daniel G. Poiré24, Simon W. Poulton25, Robert Riding26, Mukund Sharma27, Craig Storey2, Eva Stueeken28, Rosalie Tostevin29, Elizabeth Turner30, Shuhai Xiao31, Shuanhong Zhang32, Ying Zhou1 and Maoyan Zhu33 1 Department of Earth Sciences, University College London, London, UK 2 School of the Environment, Geography and Geosciences, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK 3 Department of Earth Science, University of California at Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA 4 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Canada 5 Geoscience Australia (retired), Canberra, Australia 6 Instituto de Geociências, Universidade de Brasília, Brasilia, Brazil 7 Department of Geology, University of Delhi, Delhi, India 8 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Riverside, -

Facies, Phosphate, and Fossil Preservation Potential Across a Lower Cambrian Carbonate Shelf, Arrowie Basin, South Australia

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 533 (2019) 109200 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Facies, phosphate, and fossil preservation potential across a Lower Cambrian T carbonate shelf, Arrowie Basin, South Australia ⁎ Sarah M. Jacqueta,b, , Marissa J. Bettsc,d, John Warren Huntleya, Glenn A. Brockb,d a Department of Geological Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA b Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales 2109, Australia c Palaeoscience Research Centre, School of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales 2351, Australia d Early Life Institute and Department of Geology, State Key Laboratory for Continental Dynamics, Northwest University, Xi'an 710069, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The efects of sedimentological, depositional and taphonomic processes on preservation potential of Cambrian Microfacies small shelly fossils (SSF) have important implications for their utility in biostratigraphy and high-resolution Calcareous correlation. To investigate the efects of these processes on fossil occurrence, detailed microfacies analysis, Organophosphatic biostratigraphic data, and multivariate analyses are integrated from an exemplar stratigraphic section Taphonomy intersecting a suite of lower Cambrian carbonate palaeoenvironments in the northern Flinders Ranges, South Biominerals Australia. The succession deepens upsection, across a low-gradient shallow-marine shelf. Six depositional Facies Hardgrounds Sequences are identifed ranging from protected (FS1) and open (FS2) shelf/lagoonal systems, high-energy inner ramp shoal complex (FS3), mid-shelf (FS4), mid- to outer-shelf (FS5) and outer-shelf (FS6) environments. Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling ordination and two-way cluster analysis reveal an underlying bathymetric gradient as the main control on the distribution of SSFs. -

Late Permian to Middle Triassic Palaeogeographic Differentiation of Key Ammonoid Groups: Evidence from the Former USSR Yuri D

Late Permian to Middle Triassic palaeogeographic differentiation of key ammonoid groups: evidence from the former USSR Yuri D. Zakharov1, Alexander M. Popov1 & Alexander S. Biakov2 1 Far-Eastern Geological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences (Far Eastern Branch), Stoletija Prospect 159, Vladivostok, RU-690022, Russia 2 North-East Interdisciplinary Scientific Research Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences (Far Eastern Branch), Portovaja 16, Magadan, RU-685000, Russia Keywords Abstract Ammonoids; palaeobiogeography; palaeoclimatology; Permian; Triassic. Palaeontological characteristics of the Upper Permian and upper Olenekian to lowermost Anisian sequences in the Tethys and the Boreal realm are reviewed Correspondence in the context of global correlation. Data from key Wuchiapingian and Chang- Yuri D. Zakharov, Far-Eastern Geological hsingian sections in Transcaucasia, Lower and Middle Triassic sections in the Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences (Far Verkhoyansk area, Arctic Siberia, the southern Far East (South Primorye and Eastern Branch), Vladivostok, RU-690022, Kitakami) and Mangyshlak (Kazakhstan) are examined. Dominant groups of Russia. E-mail: [email protected] ammonoids are shown for these different regions. Through correlation, it is doi:10.1111/j.1751-8369.2008.00079.x suggested that significant thermal maxima (recognized using geochemical, palaeozoogeographical and palaeoecological data) existed during the late Kun- gurian, early Wuchiapingian, latest Changhsingian, middle Olenekian and earliest Anisian periods. Successive expansions and reductions of the warm– temperate climatic zones into middle and high latitudes during the Late Permian and the Early and Middle Triassic are a result of strong climatic fluctuations. Prime Middle–Upper Permian, Lower and Middle Triassic Bajarunas (1936) (Mangyshlak and Kazakhstan), Popov sections in the former USSR and adjacent territories are (1939, 1958) (Russian northern Far East and Verkhoy- currently located in Transcaucasia (Ševyrev 1968; Kotljar ansk area) and Kiparisova (in Voinova et al. -

Tectonic Regimes in the Baltic Shield During the Last 1200 Ma • a Review

Tectonic regimes in the Baltic Shield during the last 1200 Ma • A review Sven Åke Larsson ' ', Bva-L^na Tuliborq- 1 Department of Geology Chalmers University of Technology/Göteborij U^vjrsivy 2 Terralogica AB November 1993 TECTONIC REGIMES IN THE BALTIC SHIELD DURING THE LAST 1200 Ma - A REVIEW Sven Åke Larsson12, Eva-Lena Tullborg2 1 Department of Geology, Chalmers University of Technology/Göteborg University 2 Terralogica AB November 1993 This report concerns a study which was conducted for SKB. The conclusions and viewpoints presented in the report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily coincide with those of the client. Information on SKB technical reports from 1977-1978 (TR 121), 1979 (TR 79-28), 1980 (TR 80-26), 1981 (TR 81-17), 1982 (TR 82-28), 1983 (TR 83-77), 1984 (TR 85-01), 1985 (TR 85-20), 1986 (TR 86-31), 1987 (TR 87-33), 1988 (TR 88-32),. 1989 (TR 89-40), 1990 (TR 90-46), 1991 (TR 91-64) and 1992 (TR 92-46) is available through SKB. ) TECTONIC REGIMES IN THE BALTIC SHIELD DURING THE LAST 1200 Ma - A REVIEW by Sven Åke Larson and Eva-Lena Tullborg Department of Geology, Chalmers University of Technology / Göteborg University & Terralogica AB Gråbo, November, 1993 Keywords: Baltic shield, Tectonicregimes. Upper Protero/.oic, Phanerozoic, Mag- matism. Sedimentation. Erosion. Metamorphism, Continental drift. Stress regimes. , ABSTRACT 1 his report is a review about tectonic regimes in the Baltic (Fennoscandian) Shield from the Sveeonorwegian (1.2 Ga ago) to the present. It also covers what is known about palaeostress during this period, which was chosen to include both orogenic and anorogenic events. -

The Ordovician Succession Adjacent to Hinlopenstretet, Ny Friesland, Spitsbergen

1 2 The Ordovician succession adjacent to Hinlopenstretet, Ny Friesland, Spitsbergen 3 4 Björn Kröger1, Seth Finnegan2, Franziska Franeck3, Melanie J. Hopkins4 5 6 Abstract: The Ordovician sections along the western shore of the Hinlopen Strait, Ny 7 Friesland, were discovered in the late 1960s and since then prompted numerous 8 paleontological publications; several of them are now classical for the paleontology of 9 Ordovician trilobites, and Ordovician paleogeography and stratigraphy. Our 2016 expedition 10 aimed in a major recollection and reappraisal of the classical sites. Here we provide a first 11 high-resolution lithological description of the Kirtonryggen and Valhallfonna formations 12 (Tremadocian –Darriwilian), which together comprise a thickness of 843 m, a revised bio-, 13 and lithostratigraphy, and an interpretation of the depositional sequences. We find that the 14 sedimentary succession is very similar to successions of eastern Laurentia; its Tremadocian 15 and early Floian part is composed of predominantly peritidal dolostones and limestones 16 characterized by ribbon carbonates, intraclastic conglomerates, microbial laminites, and 17 stromatolites, and its late Floian to Darriwilian part is composed of fossil-rich, bioturbated, 18 cherty mud-wackestone, skeletal grainstone and shale, with local siltstone and glauconitic 19 horizons. The succession can be subdivided into five third-order depositional sequences, 20 which are interpreted as representing the SAUK IIIB Supersequence known from elsewhere 21 on the Laurentian -

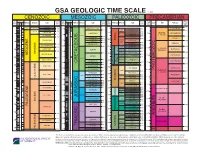

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

What Really Happened in the Late Triassic?

Historical Biology, 1991, Vol. 5, pp. 263-278 © 1991 Harwood Academic Publishers, GmbH Reprints available directly from the publisher Printed in the United Kingdom Photocopying permitted by license only WHAT REALLY HAPPENED IN THE LATE TRIASSIC? MICHAEL J. BENTON Department of Geology, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. (Received January 7, 1991) Major extinctions occurred both in the sea and on land during the Late Triassic in two major phases, in the middle to late Carnian and, 12-17 Myr later, at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary. Many recent reports have discounted the role of the earlier event, suggesting that it is (1) an artefact of a subsequent gap in the record, (2) a complex turnover phenomenon, or (3) local to Europe. These three views are disputed, with evidence from both the marine and terrestrial realms. New data on terrestrial tetrapods suggests that the late Carnian event was more important than the end-Triassic event. For tetrapods, the end-Triassic extinction was a whimper that was followed by the radiation of five families of dinosaurs and mammal- like reptiles, while the late Carnian event saw the disappearance of nine diverse families, and subsequent radiation of 13 families of turtles, crocodilomorphs, pterosaurs, dinosaurs, lepidosaurs and mammals. Also, for many groups of marine animals, the Carnian event marked a more significant turning point in diversification than did the end-Triassic event. KEY WORDS: Triassic, mass extinction, tetrapod, dinosaur, macroevolution, fauna. INTRODUCTION Most studies of mass extinction identify a major event in the Late Triassic, usually placed at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary.