Mapping Indian Art Criticism Post Independence Final 20110808

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

LSE Review of Books: Book Review: Radio Empire: the BBC's Eastern

LSE Review of Books: Book Review: Radio Empire: The BBC’s Eastern Service and the Emergence of the Global Anglophone Novel by Daniel Ryan Morse Page 1 of 4 Book Review: Radio Empire: The BBC’s Eastern Service and the Emergence of the Global Anglophone Novel by Daniel Ryan Morse In Radio Empire: The BBC’s Eastern Service and the Emergence of the Global Anglophone Novel, Daniel Ryan Morse draws attention to the dynamic intersections between literature and radio, exploring how the BBC’s Eastern Service, directed at educated Indian audiences, influenced the development of global Anglophone literature and literary broadcasting. Pushing against the siloed ways in which literary modernism is often studied, this fresh and ambitious book reveals the profound impact of the BBC’s Eastern Service on the printed and broadcast word, finds Diya Gupta. Radio Empire: The BBC’s Eastern Service and the Emergence of the Global Anglophone Novel. Daniel Ryan Morse. Columbia University Press. 2020. Find this book (affiliate link): In Indian writer Mulk Raj Anand’s novel The Big Heart (1945), student leader Satyapal listens to Azad Hind Radio during the Second World War. These broadcasts by political radical Subhas Chandra Bose were trying to influence Indian ‘hearts and minds’ against British imperialism by using German radio services from 1942 onwards. On the other hand, the poet Purun Singh Bhagat, another character in the same novel, declares that the English are ‘on the side of truth against falsehood’ (1). Yet, curiously, neither Bhagat nor any others in the novel are depicted as listening to the BBC. -

Contemporary Art in Indian Context

Artistic Narration, Vol. IX, 2018, No. 2: ISSN (P) : 0976-7444 (e) : 2395-7247Impact Factor 6.133 (SJIF) Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Richa Singh Asso. Prof., Research Scholar Deptt. of Drawing & Painting M.F.A. M.M.H. College B.Ed. Ghaziabad, U.P. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Abstract: This article has a focus on Contemporary Art in Indian context. Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Through this article emphasizesupon understanding the changes in Richa Singh, Contemporary Art over a period of time in India right from its evolution to the economic liberalization period than in 1990’s and finally in the Contemporary Art in current 21st century. The article also gives an insight into the various Indian Context, techniques and methods adopted by Indian Contemporary Artists over a period of time and how the different generations of artists adopted different techniques in different genres. Finally the article also gives an insight Artistic Narration 2018, into the current scenario of Indian Contemporary Art and the Vol. IX, No.2, pp.35-39 Contemporary Artists reach to the world economy over a period of time. key words: Contemporary Art, Contemporary Artists, Indian Art, 21st http://anubooks.com/ Century Art, Modern Day Art ?page_id=485 35 Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai, Richa Singh Contemporary Art Contemporary Art refers to art – namely, painting, sculpture, photography, installation, performance and video art- produced today. Though seemingly simple, the details surrounding this definition are often a bit fuzzy, as different individuals’ interpretations of “today” may widely vary. -

NAVJOT ALTAF Selected Biography

1260 Carillion Point nyb@nybgallery Kirkland, WA 98033, USA +1 425 466 1776 NAVJOT ALTAF Selected biography From Meerut, India. Education Fine and Applied Arts, Sir J.J. School of Arts, Mumbai, India Graphics, Garhi Studios, New Delhi, India Solo Exhibitions 2018 Lost Text, The Guild Gallery, Alibaug, India. Lost Text, Special Project, Art Fair, New Delhi, The Guild Gallery, India. 2016 How Perfect Perfection Can Be Installation with drawings, sculptures, soil, rice grain, and video, Chemould Prescott Road Art Gallery, Mumbai, India. Catalogue. 2015 How Perfect Perfection Can Be Installation with drawings, sculptures, soil, rice grain, and video, The Guild Gallery Alibaug, India. 2013 Horn in the Head, Sculpture Installation with audio and video, Talwar Gallery, New Delhi, India. 2010 TOUCH IV22 monitors video installation, Talwar Gallery, New Delhi, The Guild, Bombay, India. A place in NY, Photomontage, The Guild Gallery, Bombay and NY, USA. Catalogue. 2009 Lacuna in Testimony - Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum, Florida, USA. 2008 Touch 4 projection video installation and interactive sculptures, Sakshi Gallery, Bombay, India. Bombay Shots- Photomontage, The Guild Gallery, Bombay, India. Catalogue. 2006 Jagar Multimedia Installation, and Water Weaving, video Installation, Sakshi Gallery, Bombay, India. Junctions 1 – 2 – 3 Photo installation with sound, The Guild Gallery, Bombay, India. Catalogue. 2005 Water Weaving, Video Installation, Talwar Gallery, NY, USA. Catalogue. 2004 Bombay Meri Jaan and 'Lacuna in Testimony', video Installation, Sakshi Gallery, Bombay, India. Catalogue. 2003 In Response To, sculpture installation with photographs by Ravi Agarwal, Talwar Gallery, NY, USA. Catalogue. Displaced Self, Interactive project with artists from Israel and Ireland, Sakshi gallery, Bombay, India. -

The Rise and Fall of the Bilingual Intellectual

PERSPECTIVE and Kannada and Hindi passably. He also The Rise and Fall of the has a reading knowledge of French and German. On the other hand, Mukul Kesa- Bilingual Intellectual van and I are essentially comfortable in English alone. We can speak Hindi conver- sationally, and use documents written in Ramachandra Guha Hindi for research purposes. But we can- not write scholarly books or essays in Hin- This essay interprets the rise and 1 di. And neither of us can pretend to a third fall of the bilingual intellectual in his essay is inspired by an argu- language at all. modern India. Making a ment between the scholar-librarian TB S Kesavan and his son Mukul that 2 distinction between functional I was once privy to. I forget what they were Let me move now from the personal to the and emotional bilingualism, it fighting about. But I recall that the father, historical, to an argument on the question argues that Indian thinkers, then past 90 years of age, was giving as of language between two great modern writers and activists of earlier good as he got. At periodic intervals he Indians. In the month of April 1921, would turn to me, otherwise a silent spec- M ahatma Gandhi launched a broadside generations were often tator, and pointing to his son, say: against English education. First, in a intellectually active in more than “makku!”, “paithyam”! Those were words speech in Orissa, he described it as an one language. Now, however, that Mukul, born in Delhi of a Hindi- “unmitigated evil”. -

Exhibition Brochure

‘Now that the trees have spoken’ Ranjit Hoskote ‘Now that the trees have spoken’ presents the work of four artists: Bhuri Bai, Ladoo Bai, Narmada Prasad Tekam and Ram Singh Urveti. Their paintings, which are being exhibited in Mumbai for the first time, form part of a collection built up over the last five years by Dadiba Pundole. They way-mark the process of dialogue that this Bombay-based gallerist and collector has enjoyed with the artists, in the course of his research trips into central India. Born and raised in Madhya Pradesh, the protagonists of ‘Now that the trees have spoken’ represent that emergent third field of artistic production in contemporary Indian culture which is neither metropolitan nor rural, neither (post)modernist nor traditional, neither derived from academic training nor inherited without change from tribal custom. Indeed, as theorists and curators actively engaged with mapping this third field (including J Swaminathan, Jyotindra Jain, Gulammohammed Sheikh and Nancy Adajania) have demonstrated, descriptions such as ‘tribal’ and ‘folk’, although still used as convenient shorthand, are worse than useless. Generated from the typological obsessions of the colonial census, these labels have long been responsible for a dreadful incarceration. They have reduced thousands of individuals to the happenstance of birth, registering them primarily as bearers of community identities rather than as citizens of a Republic. And, once circumscribed as Warlis, Bhils, Gonds or Saoras, these individuals have had to mortgage their free-floating, self-renewing imaginative energies to the regime of the emporium. None of the four artists presented in ‘Now that the trees have spoken’ inherits a primordial ‘folk art’. -

Shuvaprasanna Bhattacharya — Concise Bio

Shuvaprasanna Bhattacharya — Concise Bio Major Solo Exhibitions − 2011 'Shuvaprasanna: Recent Works', Centre of International Modern Art (CIMA), Kolkata − 2011 Traveling Retrospective at Lalit Kala Akademi; Art Indus; Gallery Nvya, New Delhi; Tao Art Gallery, New Delhi − 2008 ‘Night Watch’, Art Alive Gallery, New Delhi − 2007 ‘Madhura: The Golden Flute’, organized by Indian Contemporary at Visual Arts Centre, Hong Kong − 2006 ‘Evocative Expressions: In Quest of Krishna’, Art Alive Gallery, New Delhi − 2006 ‘Evocative Expressions: In Quest of Krishna’, ITC Sonar Bangla Art Gallery, Kolkata − 2006 ‘The Divine Flute’, Aicon Gallery, USA − 2005 ‘The Golden Flute’, organized by Indian Fine Art at Cymroza Art Gallery, Mumbai − 2004 ‘Lila’, organized by Art Indus, New Delhi at Shridharni Art Gallery, New Delhi − 2004 ‘The Divine Flute’, Gallery ArtsIndia, New York − 2002 ‘Icons and Illusions’, Gallery Arts India, New York − 2002 ‘Madhura’, Art Indus, New Delhi − 2000 ‘Shuvaprasanna’s Icon and Retrospective’, organized by Art Indus at Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, New Delhi − 2000 Fine Art Company, Mumbai − 2000 Gallery Sumukha, Bangalore − 2000 Art world, Chennai − 1998 ‘An Appreciation of Ted Hughes’, Exhibition of Crow Paintings, British Council, Kolkata − 1998 Art Indus, New Delhi − 1995 Painters Home Gallery, Kolkata − 1995 Gallery Sanskritii, New Delhi − 1994 Vadhera Art Gallery, New Delhi − 1994 Galerie Grewal Mohanjeet, Paris, France − 1993 ‘Metropolis’, Portraits of Calcutta, Centre for International Modern Art (CIMA), Kolkata -

'Introspection' in Nissim Ezekiel's Poetry:A Brief Note

INFOKARA RESEARCH ISSN NO: 1021-9056 Theme of Alienation and ‘Introspection’ in Nissim Ezekiel’s Poetry:A brief Note M.Jayashree, Ph.D Scholar in English (P.T), E.M.G.Yadava College for Women, MADURAI – 625 014. Tamil Nadu, India. Abstract:This is an attempt to project Nissim Ezekiel as one of the major poets in Indian English literature in the current literary scenario, who is the one gifted with the power of influencing the theory and practice of several younger poets in addition to his own pioneering creative contribution to Indian poetry in English. It examines rather significantly how Ezekiel stands for simplicity, clarity, coherence, lucidity in art and literature and his poetic skill in treatment of various themes like loneliness, alienation and introspection, by bringing home the point that his poetry, acclaimed for its quality and vivacity, renders the contemporary themes of alienation, spiritual emptiness, isolation and fragmentation with humor, compassion and irony. Keywords: literary scenario, theory, practice, creative contribution, art, literature, alienation, introspection, compassion irony. Nissim Ezekiel, one of the major poets in Indian English literature, has expressed valuable ideas on literature and life in his letters, critical writings, poetic compositions and also interviews. He was in the vanguard of Indian poets writing in English. Much feted and acclaimed during his life time, Ezekiel was born on 6th Dec, 1924 in Bombay to Jewish (Bene-Israel) parents, who were deeply involved in education. He had his schooling at Antonio D’Souza High School and then studied at Wilson College, Bombay and later at Birbeck College, London (1948-52). -

Dtpage01april28.Qxd (Page 1)

DLD‰‰†‰KDLD‰‰†‰DLD‰‰†‰MDLD‰‰†‰C JLo and behold! Priyanka’s new THE TIMES OF INDIA Jen’s childhood Andaaz bowls Monday, April 28, 2003 isn’t a sob story Bollywood over Page 7 Page 8 TO D AY S LUCKY 832 Jim carrey s teeth T ime for fun 841 888 Two fat ladies Two little ducks 822 Your Dambola Ticket available in Delhi Times on 27th April, 2003 OF INDIA Numbers already announced : 27, 39, 50, 71 MANOJ KESHARWANI Metro breaks new ground at CP ARUN KUMAR DAS Sabha, Civil Lines, Kashmere Gate, the Times News Network New Delhi railway station, Barakham- ba Road, Patel Chowk and the Central he 1 km stretch between Patel Secretariat. Chowk and Connaught Place is CP is, of course, the largest of the Tan uninterrupted journey —but underground stations covered by this only if one undertakes the journey via route. ‘‘The CP station will be equipped a tunnel 20 m below the surface of ter- with four subways opening to ticket ha- ra firma. Higher up, on the ground JAISWAL SATISH lls and bearing large roof-like structur- above, there is a frenzy of construction es. The entire area will be landscaped activity.The Delhi Metro Rail Corpora- to impart a grand look,’’ says Dayal. tion (DMRC) is on the job and busy put- ‘‘To ensure that work on the metro is ting CP on the fast track by laying down TUNNEL VISION conducted smoothly,utilities along var- two-way metro tracks. Work on the underground section of the metro is moving on the right track ious routes have been diverted via ‘‘This underground tunnel is being diaphragm walls.’’ constructed with the help of two state- While the DMRC has made slow and ing DU and ISBT; and the second phase While all metro-station platforms of-the art boring machines procured fr- steady progress so far, it still has a long covering the route between ISBT and will be equipped with AC and escala- om Germany at a cost of Rs 40 crore ea- way to go in that the total length of the the Central Secretariat. -

Ranjit Hoskote: Signposting the Indian Highway Ranjit Hoskote

HERNING MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART Ranjit Hoskote: Signposting the Indian Highway Ranjit Hoskote You Can’t Drive Down the Same Highway Twice… …as Ed Ruscha might have said to Heraclitus. But to begin this story properly: two artists, two highways, two time horizons a decade apart in India. Atul Dodiya’s memorable painting, ‘Highway: For Mansur’, was first shown at his 1999Vadehra Art Gallery solo exhibition in New Delhi. The painting is dominated by a pair of vultures, a quotation culled from the folios of the Mughal artist Mansur; the birds look down on a highway that cuts diagonally across a desert. The decisiveness of this symbol of progress is negated by a broken-down car that stands right in the middle of it. The sun beats down on the marooned driver, whose ineffectual attempts at repairing his vehicle are viewed with interest by the predators. In the lower half of the frame, Dodiya inserts an enclosure in which a painter, identifiably the irrepressible satirist and gay artist Bhupen Khakhar, bends over his work. Veined with melancholia as well as quixotic humour, this painting prompts several interpretations. Does the car symbolise the fate of painting as an artistic choice, at a time when new media possibilities were opening up; is the car shorthand for the project of modernism? Or is this an elegy for the beat-up postcolonial nation-state, becalmed in the dunes of globalisation? In an admittedly summary reading, ‘Highway: For Mansur’ could be viewed as an allegory embodying a dilemma that has immobilised the artist, even as he contemplates flamboyant encounters with history in the confines of his studio. -

Catalogue Fair Timings

CATALOGUE Fair Timings 28 January 2016 Thursday Select Preview: 12 - 3pm By invitation Preview: 3 - 5pm By invitation Vernissage: 5 - 9pm IAF VIP Card holders (Last entry at 8.30pm) 29 - 30 January 2016 Friday and Saturday Business Hours: 11am - 2pm Public Hours: 2 - 8pm (Last entry at 7.30pm) 31 January 2016 Sunday Public Hours: 11am - 7pm (Last entry at 6.30pm) India Art Fair Team Director's Welcome Neha Kirpal Zain Masud Welcome to our 2016 edition of India Art Fair. Founding Director International Director Launched in 2008 and anticipating its most rigorous edition to date Amrita Kaur Srijon Bhattacharya with an exciting programme reflecting the diversity of the arts in Associate Fair Director Director - Marketing India and the region, India Art Fair has become South Asia's premier and Brand Development platform for showcasing modern and contemporary art. For our 2016 Noelle Kadar edition, we are delighted to present BMW as our presenting partner VIP Relations Director and JSW as our associate partner, along with continued patronage from our preview partner, Panerai. Saheba Sodhi Vishal Saluja Building on its success over the past seven years, India Art Senior Manager - Marketing General Manager - Finance Fair presents a refreshed, curatorial approach to its exhibitor and Alliances and Operations programming with new and returning international participants Isha Kataria Mankiran Kaur Dhillon alongside the best programmes from the subcontinent. Galleries, Vip Relations Manager Programming and Client Relations will feature leading Indian and international exhibitors presenting both modern and contemporary group shows emphasising diverse and quality content. Focus will present select galleries and Tanya Singhal Wol Balston organisations showing the works of solo artists or themed exhibitions. -

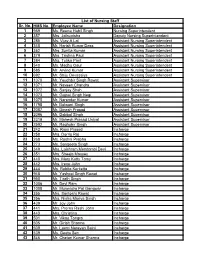

Sr. No. HMS No. Employee Name Designation 1 959 Ms. Reena Habil Singh Nursing Superintendent 2 357 Mrs

List of Nursing Staff Sr. No. HMS No. Employee Name Designation 1 959 Ms. Reena Habil Singh Nursing Superintendent 2 357 Mrs. Jaibunisha Deputy Nursing Superintendent 3 285 Ms. Vijay A Lal Assistant Nursing Superintendent 4 348 Mr. Harish Kumar Dass Assistant Nursing Superintendent 5 362 Mrs. Sunita Kumar Assistant Nursing Superintendent 6 379 Mrs. Trishna Paul Assistant Nursing Superintendent 7 384 Mrs. Tulika Pant Assistant Nursing Superintendent 8 540 Ms. Madhu Gaur Assistant Nursing Superintendent 9 585 Mr. Arvind Kumar Assistant Nursing Superintendent 10 692 Mr. Shiju Devassiya Assistant Nursing Superintendent 11 1070 Mr. Youdhbir Singh Rawat Assistant Supervisor 12 1071 Mr. Naveen Chandra Assistant Supervisor 13 1072 Mr. Sanjay Shah Assistant Supervisor 14 1073 Mr. Gajpal Singh Negi Assistant Supervisor 15 1075 Mr. Narender Kumar Assistant Supervisor 16 1798 Mr. Balwant Singh Assistant Supervisor 17 2087 Mr. Dinesh Prasad Assistant Supervisor 18 2096 Mr. Dabbal Singh Assistant Supervisor 19 2319 Mr. Mahesh Prasad Uniyal Assistant Supervisor 20 2592 Mr. Raghubir Singh Assistant Supervisor 21 242 Ms. Rajni Prasad Incharge 22 258 Mrs. Dorris Raj Incharge 23 268 Ms. Roshni Prabha Incharge 24 273 Ms. Sangeeta Singh Incharge 25 349 Mrs. Laishram Memtombi Devi Incharge 26 351 Mrs. Sheeja Massey Incharge 27 440 Mrs. Mary Kutty Tomy Incharge 28 442 Mrs. Irene John Incharge 29 444 Ms. Rubita Kerketta Incharge 30 948 Mr. Yashpal Singh Rawat Incharge 31 950 Mr. Tirath Singh Incharge 32 1006 Mr. Devi Ram Incharge 33 1008 Mr. Munendra Pal Gangwar Incharge 34 355 Mrs. Santoshi Rawat Incharge 35 356 Mrs. Nisha Mariya Singh Incharge 36 439 Mr.