Which River Stour?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whose River? London and the Thames Estuary, 1960-2014* Vanessa Taylor Univ

This is a post-print version of an article which will appear The London Journal, 40(3) (2015), Special Issue: 'London's River? The Thames as a Contested Environmental Space'. Accepted 15 July 2015. Whose River? London and the Thames Estuary, 1960-2014* Vanessa Taylor Univ. of Greenwich, [email protected] I Introduction For the novelist A.P. Herbert in 1967 the problem with the Thames was simple. 'London River has so many mothers it doesn’t know what to do. ... What is needed is one wise, far- seeing grandmother.’1 Herbert had been campaigning for a barrage across the river to keep the tide out of the city, with little success. There were other, powerful claims on the river and numerous responsible agencies. And the Thames was not just ‘London River’: it runs for over 300 miles from Gloucestershire to the North Sea. The capital’s interdependent relationship with the Thames estuary highlights an important problem of governance. Rivers are complex, multi-functional entities that cut across land-based boundaries and create interdependencies between distant places. How do you govern a city that is connected by its river to other communities up and downstream? Who should decide what the river is for and how it should be managed? The River Thames provides a case study for exploring the challenges of governing a river in a context of changing political cultures. Many different stories could be told about the river, as a water source, drain, port, inland waterway, recreational amenity, riverside space, fishery, wildlife habitat or eco-system. -

Crossing the Thames Estuary Second Edition Updates

Crossing the Thames Estuary Second Edition Updates Update No 5a There is one specific update (changes to buoyage in the Middle Deep) and three ‘news’ items. Please note a single small typo in this Update No 5 has been changed with effect from 7th January, 2016. There is also a typo in Rolling Road for Route 11 on Page 67. The title of the Route should read “11 – Ramsgate to River Colne”. The rest of the Route is correct. Some additional images to use ‘cut and paste’ amendments for the Rolling Route are added to Update 5a. Item 1 – Middle Deep Trinity House have announced their intention, in their NtM No 23 of 2015, to move and rename the three buoys currently in northern arm of the West Swin “on or around” 14th September, 2015. The buoys to be moved are the South Whitaker, West Hook and N.E. Maplin. The technical detail and name change is: S. Whitaker Lighted Buoy: to be moved to 51° 39’.536N., 001° 09’.393E., and to be renamed ‘Maplin Approach’. W. Hook Middle Lighted Buoy: to be moved to 51° 38'.290N., 001° 08'.862E., and to be renamed ‘East Maplin’. N.E. Maplin Lighted Buoy: to be moved to 51° 36'.776N., 001° 05'.501E., and to be renamed ‘Maplin Middle’. The new positions will be as shown overleaf. East Coast Pilot has made enquiries of Trinity House as to the reason for these moves and whilst there is at the moment no suggestion that the Shoeburyness Firing Range is extending its boundaries, the former buoyage did bring shipping and yachts in very close proximity to the edge of the Range and the re‐positioning is intended to reduce the risk of encroachment. -

Hydrographic and Tidal Information for Deep Draught Ships in a Tidal Estuary

HYDROGRAPHIC AND TIDAL INFORMATION FOR DEEP DRAUGHT SHIPS IN A TIDAL ESTUARY by Lt. Commander J. C. E. W h i t e , R.N., (Retd.) Port of London Authority This paper was presented at the XHIth International Congress of Surveyors (F.I.G.) in Wiesbaden, September 1971 SUMMARY The principal oil refineries in the Port of London are situated at Thameshaven and Coryton, over 50 miles from the true entrance to the port at Long Sand Head. Here deep draught tankers first enter areas where charted depths are less than their draught and so require the tide to give sufficient water to navigate. This 50 mile passage is through a complex estuary, where drying sandbanks alternate with deeps; and where two tidal systems (that from the North Sea and that from the Straits of Dover) meet and interact with resultant instability of the sea bed in certain areas; some 12 miles of this passage are dredged. To bring into the Port ships drawing up to 48 feet (100 000 ton tankers fully laden and 200 000 ton tankers part laden) with an underkeel clearance of only 3 -4 feet requires great skill on the part of the Master and Pilot and this skill must have a sound basis of up-to-date data. They must have accurate hydrographic surveys and actual tidal heights, as well as compre hensive tidal predictions to enable them to plan and execute the passage with safety. This paper discusses the hydrographic surveys required for this pur pose in terms of accuracy of measured depth, tidal reduction of soundings, and accuracy of position fixing and how this is applied in the Port of Lon don. -

![Apr£/ 10, R8go] NATURE 539](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5157/apr%C2%A3-10-r8go-nature-539-2355157.webp)

Apr£/ 10, R8go] NATURE 539

Apr£/ 10, r8go] NATURE 539 THE THAMES ESTUARY. When beacons are erected on any of the banks, or a ship gets on shore, the tidal streams scour out the sand in the ALTHOUGH it is not practicable to say precisely immediate neighbourhood, and cause the wrecks to sink where the river ends and the estuary commences, and finally disappear. Although without actual boring it it will be sufficient for general purposes if the westward, is not possible to give the exact depth of these sands, it or inner, boundary of the Thames estuary is assumed to is probable that they are upwards of 6o feet thick, for be a line from Southend to Sheerness, the northern channels of that depth have opened out across the sands boundary as the coast of Essex, and the southern the and ngain closed up, so that the bank has been dry at coast of Kent ; and it may be said to extend eastward to low water where 6o feet formerly existed ; and the Good the meridian of the Kentish Knock light-vessel. The win Sands, in the Downs, which have been bored, proved area inclosed between these lines is upwards of 8oo to be So fe et in thickness. All the banks, and the channels square nautical miles, and the whole of the space is en between them, trend in a north-east and south-west direc cumbered with banks, between whi<:h are the several tion : this is doubtless due to the fact that the stream channels leading to the river. outside the estuary is running to the northward whilst As the shores of Essex and Kent are low, and have no the tide is ebbing from the river, and, consequently, the natural features by which they may be distinguished at a ebb stream in the estuary is deflected to the north-east distance, and as a great part of the estuary is out of sight ward. -

Manveer, Kate, Please See Attached

From: CARPENTER Matthew To: "Thanet Extension"; Thanet Extension Cc: OWEN Robbie Subject: Port of Tilbury London Limited and London Gateway Port Limited Deadline 4C submission [PM- AC.FID3789724] Date: 10 April 2019 20:44:32 Attachments: PoTLL and LGPL - Deadline 4C submission.PDF Appendix 1 HRW Report.PDF Manveer, Kate, Please see attached the Deadline 4C submissions of PoTLL and LGPL. In accordance with the Rule 8(3) letter dated 4 April 2019 we shall also forward the contents on to the listed IPs who we have been able to obtain contact details for. Kind regards, Matthew Carpenter Solicitor for Pinsent Masons LLP D: +44 20 7667 7205 M: I: 817205 [email protected] www.pinsentmasons.com www.Out-Law.com Winner – ‘Law Firm of the Year’ at The Lawyer Awards 2018 Ranked No.1 Legal Planning team by Planning Magazine in 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018 Proud to have been named Stonewall Employer of the Year in the Stonewall Top 100 Employers 2019 PLEASE NOTE: We have amended our Standard Terms of Business to cover the UK leaving the EU. They are limited changes to the data protection provisions. There are equivalent changes proposed for clients with non-standard terms. Please click here for full details of the changes. IMPORTANT NOTICE: This email is sent on behalf of Pinsent Masons LLP, a limited liability partnership registered in England & Wales (registered number: OC333653) authorised and regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority and the appropriate regulatory body in the jurisdictions in which it operates. Its registered office is at 30 Crown Place, London EC2A 4ES. -

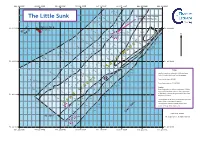

Little Sunk 2019 V1.Dpp

001.22.500E 001.23.000E 001.23.500E 001.24.000E 001.24.500E 001.25.000E 001.25.500E 001.26.000E 65 7 61 64 8 6 54 49 Remains of the former The Little Sunk 8 74 4 49 Little Sunk Beacon 6 8 4 6 44 47 4 8 7 37 54 47 66 5 35 3 3 46 1 Barrow No 2 6 42 32 27 51.42.000N 74 55 45 4 3 51.42.000N 77 5 24 Fl(2)R.5s 7 44 37 32 27 65 4 3 Barrow 75 6 7 Obstn 3 24 22 Deep 43 33 N 68 3 32 2 53 42 4 23 4 1 62 5 3 25 8 36 14 76 73 58 4 42 3 34 28 7 4 6 27 28 65 53 41 26 6 75 6 5 3 33 2 11 42 9 34 32 5 56 46 32 24 12 7 36 5 5 43 34 3 28 22 64 3 28 2 46 5 315 126 6 43 4 4 29 1 1 33 2 82 128 7 54 37 36 5 9 41 3 29 2 11 7 5 42 4 2 4 9 72 36 47 3 3 79 63 41 38 2 27 4 44 36 34 9 75 55 36 6 42 3 32 28 91 6 4 92 8 5 41 39 3 3 29 27 11 85 4 433 1 3 6 36 4 9 8 6 42 38 32 29 109 51.41.500N 42 3 31 29 42 5 53 37 6 51.41.500N 3 35 89 7 5 4 36 72 28 4 10 41 35 35 6 45 39 3 32 51 8 3 3 3 3 56 44 7 36 32 S a n2 d4 w a7 v e s 7 36 31 4 87 1 5 41 9812 35 3 51 Notes 6 46 4 36 2 42 3 33 7 59 8 36 34 133 42 32 4 5 Depths in metres reduced to CD based upon 8 56 37 1 9 13 8 75 4 36 32 4 6 11 5 Port of London Authority live tide gauges. -

Essex Estuaries European Marine Site

Characterisation of European Marine Sites Essex Estuaries European Marine Site Marine Biological Association Occasional Publication No. 17 Cover photograph: The River Blackwater at low tide, from the Promenade, Maldon, Essex. © Barry Samuels Site Characterisation of European Marine Sites Essex Estuaries European Marine Site B.S.Chesman, G.R.Burt & W.J. Langston 2006 A study carried out on behalf of English Nature By The Marine Biological Association, Citadel Hill, Plymouth PL1 2PB (Part of the Plymouth Marine Science Partnership) i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks are due to members of the steering group for advice and help during this project, particularly Helen Wake and Michael Coyle (English Nature) and Daniel Bastreri (Environment Agency). We are also indebted to Ms L Noble, Mrs H Treadwell and the staff of the National Marine Biological Library (NMBL) for their assistance with literature surveys. It should be noted that the opinions expressed in this report are largely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of EN. Preferred citation Chesman, B.S., Burt, G.R. & Langston, W.J. (2006). Characterisation of the European Marine Sites: Essex Estuaries European Marine Site. Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom Occasional Publication (17). pp 198. (2006) ISSN: 02602784 © 2006 by Marine Biological Association of the U.K., Plymouth Devon All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Marine Biological Association. ii 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report provides an overview of water and sediment quality within the Essex Estuaries European Marine Site (EMS) and examines evidence for their influence on biological condition. -

PRINCES CHANNEL DEVELOPMENT Recycling of Dredged Material in the Outer Thames Estuary

PRINCES CHANNEL DEVELOPMENT Recycling of Dredged Material in the Outer Thames Estuary Environmental Scoping Report August 2003 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 Scoping Study 3 1.2 Project Description 3 1.3 Study Area 7 2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 9 2.1 Princes Channel Deepening 9 2.2 Relocation Options 9 2.3 Discussion of Alternatives 10 2.4 The Dredging and Deposition Processes 11 2.5 Programme 13 3 LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 14 3.1 Regulation of Dredging 14 3.2 Deposits at Sea 14 3.3 Environmental Legislation 4 CHARACTERISATION OF RELOCATION AREAS 16 4.1 Introduction 16 4.2 Physical Characterisation 16 4.3 Biological Characterisation 20 4.4 Characterisation of the Human Environment 24 4.5 Cumulative and In-combination Effects 24 4.6 Consultation 24 5 SUMMARY OF SCOPING REQUIREMENTS 26 5.1 Scoping Requirements 26 5.2 The Environmental Assessment Process 26 6 RELEVANT REFERENCES 28 1 River Engineering, August 2003. CONTENTS continued List of Figures Figure 1 Approaches to the Port of London Figure 2 Potential Relocation Areas Figure 3 Environmental Designations in the Outer Thames Estuary Figure 4 Phase II Proposed Dredge Areas Figure 5 Existing Sediment and Water Sampling Locations Figure 6 Existing Marine Biological Survey Sampling Locations and Proposed Study Area Figure 7 Existing ADCP Tracks and Proposed ADCP Tracks Figure 8 Biomass Composition in Princes Channel Survey Area, February 2002. 2 River Engineering, August 2003. 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Scoping Study The Port of London Authority (PLA) is undertaking the deepening of Princes Channel, which forms part of the southern approaches to the Port of London, and since opportunities for beneficial use may not be sufficient to accommodate all the material to be dredged, the PLA proposes to relocate the material dredged from the channel to a site within the outer Thames Estuary. -

The Outer Thames Estuary Regional Environmental Characterisation Marine Aggregate Levy Sustainability Fund MALSF

Marine Aggregate Levy Sustainability Fund MALSF The Outer Thames Estuary Regional Environmental Characterisation Marine Aggregate Levy Sustainability Fund MALSF Cover Image Credits Main Image Top Row: Left to Right Bottom Row: Left to Right Inside Front Cover Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of Cefas Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of Emu Ltd. Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of MES Ltd. Copyright British Crown and SeaZone Solutions Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of St Andrews Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of Emu Ltd. Limited. All rights reserved. Products License University and English Heritage Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of MALSF 052008.012 Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of Cefas CD Image Credits Main Image Top Row: Left to Right Bottom Row: Left to Right Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of Emu Ltd. Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of Emu Ltd. Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of Emu Ltd. Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of St Andrews Crown Copyright 2007, Courtesy of MES Ltd. University and English Heritage Outer Thames Estuary Regional Environmental Characterisation Marine Aggregate Levy Sustainability Fund (MALSF) Administered by: Report written by: July 2009 09/J/1/06/1305/0870 MEPF 08/01 Outer Thames Estuary Regional Environmental Characterisation Outer Thames Estuary Regional Environmental Characterisation Document Release and Authorisation Record Job No: J/1/06/1305 EMU CONTACT DETAILS CLIENT CONTACT DETAILS Report No: 09/J/1/06/1305/0870 Version: 2 Emu Limited Marine Aggregate Levy Sustainability Fund (MALSF) Date: July 2009 Head Office -

Passage Planning Guide

The content of this Guide takes into account relevant information available at the time of publication; it is kept up- c Port of London Authority Copyright 2013. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by Copyright. No A Division of Kelvin Hughes Limited to-date and corrected in detail as far as is practicable. It is, however, selective, and it cannot be considered to be part of this product may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing by electronic Registered Office: New North Road, Hainault, Ilford, Essex, IG6 2UR, United Kingdom a comprehensive and authoritative statement on every aspect of the regulations and requirements applicable to means) without the prior permission of the copyright owners. Registered in England & Wales: 01030135; VAT No: GB918080917/000 TO BE USED IN CONJUNCTION WITH NAUTICAL CHARTS AND PUBLICATIONS vessels operating in the area. For fuller details of these, the relevant official publications must be consulted. The Port of London Authority, London River House, Royal Pier Road, Gravesend, Kent, DA12 2BG, UK ADMIRALTY CHARTS OF THE THAMES Southend Tide Gauge MARINERS' PASSAGE PLANNING & ROUTEING GUIDE So uth en 1183 d S An ma ch ll - THAMES ESTUARY & RIVER TO LONDON BRIDGE ora Sh 1975 ge ips 2052 Sunk Pilot Station Haven Traffic Blackwater Warning Light Le igh Sm all Sh 3750 Ancho ips Sea Reach s rage nchorage 1607 n A 8 1606 No.7 North hapma S 1609 Tide Gauge C 9 outh UKHO Chart List 6 en 6 d A nc No. Title 32.0 32.5 35.0 33.5 h 33.0 34.5 34 35.5 o F 1185 36 rag F e 365. -

Mitb83002 Part8.Pdf

Appendix D Experience+ in the United Kingdom on the Control of Discharges of Sewage Sludge to Estuarine and Coastal Waters, A Case Study INTRODUCTION In the text of this book, the physical, chemical and biological processes which take place in estuaries and coastal waters have been described in detail so far as current knowledge allows. General descriptions have also been provided on how our understanding of these processes may be used to predict the environmental impact of waste disposal on the marine environment and the assimilative capacity of the receiving waters. The conclusion has been reached that the ocean does have a capacity to receive certain wastes without damage, but that it is essential that this assimilative capacity be quantified and managed effectively through adequate controls, in order to ensure that disposal does nat give rise to adverse effects on the receiving waters, the biota present or humans as the consumer of marine resources. Due largely to its extensive coastline and the proximity of much of its population to estuaries or coastal waters, the United Kingdom UK! has a long history of discharging sewage effluent after varying degrees of treatment! directly ta estuaries and coastal waters. In addition, approximately 28 percent of the sewage sludges produced by the treatment of sewage within the UK is disposed of at sea by dumping from vessels. These dispasal practices are controlled under national and, in some cases, international regulations. Dumping of wastes at sea is regulated by the Dumping at Sea DAS! ACt 1974, and by the provisions of the Oslo and London Conventions on the prevention of marine pollution. -

Non-Technical-Summary.Pdf

1 London Array Offshore Wind Farm Environmental Statement Non-Technical Summary Introduction Contents London Array Limited consisting of Shell WindEnergy Ltd, E.ON UK Renewables Developments Ltd and CORE Ltd (referred to herein as London Array) is proposing Introduction................................3 the development of an offshore wind farm located in the Outer Thames estuary, one of the three strategic areas the Government has identified for the 2nd Round of offshore wind farm development. The Need for London Array .......................4 The proposed wind farm would be situated midway between the Kent and Essex Project Alternatives ...........................4 coastlines, more than 20 km (12 miles) from each shore. It would consist of up to 271 turbines, installed on the Long Sand and Kentish Knock banks and in the Knock Deep channel that lies between. It will occupy an area of up to 245km2 in water Consenting Requirements and Environmental depths ranging from 0 to 23 m. Impact Assessment ...........................5 The wind farm will be connected by undersea cables to a new onshore substation at Cleve Hill in North Kent. From the substation, the electricity will go into the existing The Project Construction Process ....................8 transmission network. Once completed, the installed capacity of the wind farm will be 1,000 MW, generating an average of 3,100 GWh of electricity per annum; Summary of Offshore Environmental enough to supply 750,000 homes. This is equivalent to a quarter of the domestic supply for Greater London or all of the homes in Kent and East Sussex. Impact Assessment ...........................10 Subject to obtaining the necessary planning and environmental consents and Summary of Onshore Environmental licences, construction of the onshore substation will begin in late 2006 in time for Impact Assessment ...........................16 commissioning of the first phase of the project in 2008.