Policy Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rules for Candidates Wishing to Apply for a Two Year

GENERAL 2022 1. Up to fifty Marshall Scholarships will be awarded in 2022. They are tenable at any British university and for study in any discipline at graduate level, leading to the RULES FOR CANDIDATES WISHING TO award of a British university degree. Conditions APPLY FOR A TWO YEAR MARSHALL governing One Year Scholarships are set out in a SCHOLARSHIP ONLY. separate set of Rules. Marshall Scholarships finance young Americans of high 2. Candidates are invited to indicate two preferred ability to study for a degree in the United Kingdom in a universities, although the Marshall Commission reserves system of higher education recognised for its excellence. the right to decide on final placement. Expressions of interest in studying at universities other than Oxford, Founded by a 1953 Act of Parliament, Marshall Cambridge and London are particularly welcomed. Scholarships are mainly funded by the Foreign, Candidates are especially encouraged to consider the Commonwealth and Development Office and Marshall Partnership Universities. A course search commemorate the humane ideals of the Marshall Plan facility is available here: conceived by General George C Marshall. They express https://www.marshallscholarship.org/study-in-the- the continuing gratitude of the British people to their uk/course-search American counterparts. NB: The selection of Scholars is based on our The objectives of the Marshall Scholarships are: published criteria: https://www.marshallscholarship.org/apply/criteria- • To enable intellectually distinguished young and-who-is-eligible This includes, under the Americans, their country’s future leaders, to study in academic criteria, a range of factors, including a the UK. candidate’s choice of course, choice of university, and academic and personal aptitude. -

[email protected] [email protected]

NUCCAT Members 2015/2016 N.B. bold type denotes main or only representative; Board members highlighted by grey shading Institution Representative Position Address e-mail Address/Telephone Head of Academic Policy and University of Birmingham Gillian Davis Registry, University of Birmingham, B155 2TT [email protected] I Standards T: 0121 414 2807 University of Bolton, Deane Road, Bolton, University of Bolton Richard Gill Quality Assurance Manager [email protected] I BL3 5AB T: 01204 903242 Head of Learning Enhancement and University of Bolton, Deane Road, Bolton, BL3 University of Bolton Dr Marie Norman [email protected] I Student Experience 5AB T: 01204 903213 University of Bolton Dr Anne Miller Academic Registrar University of Bolton Deane Road, Bolton, BL3 5AB [email protected] T: 01204 903832 Professor Gwendolen Director of Quality Enhancement Academic Standards & Support Unit, University of Bradford [email protected] Bradshaw and Standards Univeristy of Bradford, Richmond Road, I Bradford, BD7 1DP T: 01274 236391 Academic Standards & Support Unit, Univeristy Director of Academic Quality and University of Bradford Ms Celia Moran of Bradford, Richmond Road, Bradford, BD7 [email protected] Partnership 1DP T: 01274 235635 Academic Standards & Support Unit, Univeristy University of Bradford Laura Baxter Academic Quality Officer of Bradford, Richmond Road, Bradford, BD7 [email protected] 1DP T: 01274 235085 Unviersity College University College Birmingham, Summer Mr Robin Dutton Director of Quality Systems -

The Great British Brain Drain an Analysis of Migration to and from Manchester

The Great British Brain Drain An analysis of migration to and from Manchester Rebecca McDonald March 2019 About Centre for Cities Centre for Cities is a research and policy institute, dedicated to improving the economic success of UK cities. We are a charity that works with cities, business and Whitehall to develop and implement policy that supports the performance of urban economies. We do this through impartial research and knowledge exchange. For more information, please visit: www.centreforcities.org/about Partnerships Centre for Cities is always keen to work in partnership with like-minded organisations who share our commitment to helping cities to thrive, and supporting policymakers to achieve that aim. As a registered charity (no. 1119841) we rely on external support to deliver our programme of quality research and events. To find out more please visit: www.centreforcities.org/about/partnerships About the authors Rebecca McDonald is an Analyst at Centre for Cities: [email protected] | 0207 803 4325 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the University of Manchester for the support which has made this research possible. Centre for Cities • Manchester Brain Drain • March 2019 00. Executive summary Migration between Manchester and the rest of the North West region is very common. A third of those moving into the city came from the North West, and a third of those leaving Manchester stayed in the region. Overall, between 2009 and 2017 more people left the city to live elsewhere in the UK than moved in, leading to a net outflow of 31,620 people. Young people migrate to the city for university and work, while older graduates move away. -

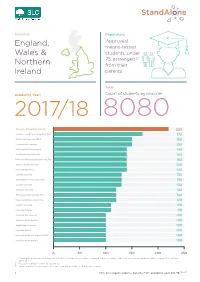

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Manchester Floor Plan Manchester Exhibitors 2020

MANCHESTER EXHIBITORS 2020 MANCHESTER University of Aberdeen 1 Cardiff Metropolitan University 33 University of Leicester 82 University of Southampton 135 University of Wolverhampton 148 HIGHER EDUCATION Abertay University 2 University of Central Lancashire 34 University of Lincoln 80 Solent University (Southampton) 136 University of Winchester 160 EXHIBITION Aberystwyth University 5 Royal Central School of Speech and Drama 95 University of Liverpool 88 University of St Andrews 137 University of Worcester 161 The Academy of Contemporary Music 3 University of Chester 35 Liverpool Hope University 79 SGS College 139 University of York 162 3 – 4 MARCH 2020 Anglia Ruskin University 4 City, University of London 121 Staffordshire University 138 83 163 Arden University 6 Coventry University 36 University of Stirling 140 Aston University 7 University for the Creative Arts 40 LMA 91 University of Strathclyde 142 Bangor University 9 University of Cumbria 39 London Metropolitan University 81 University of Suffolk 141 Supported by Barnsley College 8 De MontFort University 38 London School of Economics University of Sunderland 143 CAREER AND APPRENTICESHIP 97 and Political Science University of Bath 10 University of Surrey 144 British Army H 89 Loughborough University 84 Bath Spa University 11 University of Sussex 146 Microsoft C UCEN Manchester 92 University of Bedfordshire 12 Swansea University 149 National Apprenticeship Service A University of Derby 41 The University of Manchester 85 In association with Birmingham City University 14 Teesside University -

Impact Case Study (Ref3b) Page 1 Institution: University of Bolton Unit

Impact case study (REF3b) Institution: University of Bolton Unit of Assessment: 16 Architecture, Built Environment and Planning Title of case study: Regeneration and Facilities Management – Empowering communities through engagement 1. Summary of the impact (indicative maximum 100 words) The Regeneration and Facilities Management (FM) research programme brought together different disciplines, focused on engaging with communities of people and organisations to transfer good practice to public sector services management. It included seven members of staff, five PhD students, five grant-funded research projects, RAE2008 funded PhD projects and other non-grant projects; employing applied or action research approaches in working closely with organisations for the development and implementation of research outputs. The theme of community engagement and empowerment has resulted in organisational policy changes, improved social sustainability and continuing professional development; changing practice in public service management and strategy development. 2. Underpinning research (indicative maximum 500 words) Regeneration and FM research was started in 2007 by Dr Margaret Nelson, Reader in the Built Environment, in response to the needs of the social housing provider, Bolton at Home. The research evolved to include collaboration with a multi-disciplinary team: Dr Femi Olubodun, Senior Lecturer Quantity Surveying; Dr Mark Johnson, Reader in Applied Research in Education Technology and Systems; Stephen Powell, Reader in Inquiry-Based Learning; Richard Millwood, Reader in Distributed Learning (left 31/07/13); Rosemary Galway, Senior Lecturer Education Studies; Nooshin Akrami, Senior Lecturer Architectural Technology; Mike Lawrence Principal Lecturer (left 31/01/13); and PhD students Ebun Akinsete (completed), Roz Fox, Mohammad Tammo, Bobby Nisha-Mohammad and Rukaya Abowen-Dake. -

A Guide to Library and Information Resources Available to Social Care Employees of Cumbria County Council

A Guide to Library and Information Resources Available to Social Care Employees of Cumbria County Council Produced by: The Knowledge Management Team Adult Social Care Health and Care Services The Courts Carlisle CA3 8NA Tel: 01228 227113 Email: [email protected] June 2014 CONTENTS 1. Purpose of this Guide 3 2. Major Libraries in Cumbria for Social Care Employees 3 2.1 Cumbria Social Care Specialist Library Collection 3 2.2 Cumbria Public Libraries 3 2.3 University Hospitals NHS Trust Libraries 4 2.4 University of Cumbria 4 3. Library Partnerships in Cumbria 4 3.1 Cumbria Libraries Network (formerly known as AddLib) 4 3.2 NHS-Public Libraries Partnership 5 3.3 Passport to Partnership (P2P) Scheme 5 3.4 Cumbria Higher Education Institutions Library Partnership Scheme (CHELPS) 5 3.5 NoWAL – The North West Academic Libraries Consortium 6 4. Journal Articles 6 4.1 In-house journal subscriptions 6 4.2 Accessing journals electronically via Athens 7 4.3 Requesting journal articles via the Knowledge Management Team 7 5. Major Free Electronic Literature Databases 8 6. Useful Web Sites 9 7. Literature/ Internet Searching Service 10 2 1. Purpose of this Guide The purpose of this guide is to provide details of: Library and information services available to social care employees in Cumbria. Alternative libraries and library partnerships which employees can use. Other library and information sources (journal and organisation subscriptions, electronic literature databases, useful Web sites, Internet/ literature searching service, etc). Return to CONTENTS 2. Major Libraries in Cumbria for Social Care Employees 2.1 Cumbria Social Care Specialist Library Collection A specialist social care library collection has been developed between the Adult Social Care Knowledge Management Team and Cumbria Public Libraries. -

Greater Manchester Pastoral Support Toolkit

Greater Manchester Pastoral Support Toolkit October 2019 A Greater Manchester Pastoral Support Toolkit A Greater Manchester Pastoral Support Toolkit Contents Background Background to this Toolkit 3 Since 2018 Universities and Healthcare Providing effectual Pastoral Support is inevitably organisations across Greater Manchester have time consuming especially where the students’ collaborated in the formation of a Nurse needs are demanding. Sharing the support Studying nursing and living in Greater Manchester 4 Incentive Package. Following consultation with through appropriate use of signposting is key to those students currently studying to become the Greater Manchester best practice approach. a nurse in Greater Manchester the package is How to use the Toolkit 5 aimed at; encouraging a diverse range of The Pastoral Support Toolkit provides individuals to come and study nursing in Greater information about the pastoral support and Manchester, for those choosing Greater guidance offered within the four Greater Common triggers for concern 6 - 10 Manchester to be fully supported whilst Manchester Universities namely; Manchester completing their studies and to develop Metropolitan University, The University of Bolton, pathways to enable eventual graduates towards The University of Manchester and The University The Pastoral Support our GM Universities provide 11-14 their chosen career. A crucial element of of Salford. Additionally, Healthcare the Greater Manchester package is the Organisations across Greater Manchester The Pastoral Support our GM Healthcare Organisations provide 15-17 provision of pastoral support both within the have contributed to the toolkit by providing university and healthcare setting. Greater student placement guidance for students and Manchester recognises that studying to be a their Supervisors / Assessors. -

Never Too Late to Learn Mature Students in Higher Education About

Never Too Late To Learn Mature students in higher education About This report presents the main findings of joint research by million+ and National Union of Students (NUS) investigating the experiences of people who go to university for the first time later in life. Million+ is a university think-tank, working to solve complex problems in higher education through research and evidence-based policy. NUS is a voluntary membership organisation which makes a real difference to the lives of students and its member students' unions. We are a confederation of 600 students' unions, amounting to more than 95 per cent of all higher and further education unions in the UK. Through our member students' unions, we represent the interests of more than seven million students. Contents Contents Foreword . 1 Research findings 1) The Importance of Mature Students . 2 2) The Characteristics of Mature Students . 6 3) Opportunities and Challenges: Mature Student Experiences of Higher Education . 20 4) Maximising Talent and Opportunity in Higher Education . 37 Concluding remarks . 43 Appendix . 44 Endnotes . 50 Never Too Late To Learn Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the mature students, graduates, university staff, students’ union officers and staff, and external stakeholders who shared their stories, views and experiences during the research process. We would also like to thank Anglia Ruskin University, the University of East London, Staffordshire University, London South Bank University and the University of the West of Scotland for hosting workshops that were open to students and staff from all institutions. The conclusions are those of million+ and NUS. All errors are our own. -

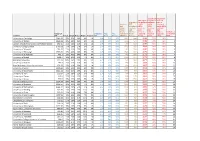

Uk University Salaries 2015-16

IN THE MONEY?: UK UNIVERSITY SALARIES 2015-16 Academics Professional and support staff Managers, directors Professor Other senior academic Other Academic total and senior officials Professional, technical and clerical Manual staff Non-academic total Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All University of Aberdeen £73,143 £80,757 £79,156 .. £114,461 £102,490 £41,830 £45,690 £44,018 £45,217 £54,483 £50,824 £58,403 £59,310 £58,896 £30,683 £35,583 £32,423 £20,122 £22,932 £22,384 £30,991 £32,832 £31,801 Abertay University .. £63,717 £63,764 .. £66,617 £66,491 £40,197 £42,258 £41,419 £42,562 £47,158 £45,441 .. £75,041 £68,896 £28,985 £31,879 £30,029 .. £23,379 £22,900 £30,084 £32,874 £31,387 Aberystwyth University £67,667 £72,679 £71,989 .. .. .. £41,757 £43,249 £42,689 £43,994 £49,324 £47,525 £46,820 £49,492 £48,423 £28,502 £30,153 £29,224 £18,075 £18,782 £18,675 £29,070 £27,845 £28,400 Anglia Ruskin University £66,238 £65,406 £65,723 £77,006 £96,030 £87,383 £43,323 £43,394 £43,357 £46,384 £49,223 £47,771 £55,661 £66,201 £60,839 £32,075 £35,007 £33,163 £22,979 £24,293 £23,787 £32,859 £35,786 £34,063 University of the Arts London £71,562 £68,132 £70,071 £78,617 £95,898 £86,768 £49,686 £48,278 £48,892 £54,437 £53,243 £53,782 £64,498 £65,740 £65,170 £35,436 £38,509 £36,596 £26,479 £26,416 £26,425 £36,752 £38,560 £37,532 Arts University Bournemouth . -

University of Cambridge 2040.39 32% 39% 24

Proportion 4 Proportion 4 GPA x [ratio & 3 [ratio of & 3 & 2 x Pctg ratio of of submitted submitted [ratio of Academic FTE staff to staff to submitted staff submitted to HESA HESA staff to HESA numbers academic academic academic academic (Profs/ staff staff staff staff SLs/Ls) numbers numbers numbers numbers Rank (based Category A Unadjusted Prop Prop from 2006-7 (Profs/ capped at capped at capped at on modified Institution FTE Pctg 4* Pctg 3* Pctg 2* Pctg 1* Pctg U/C GPA 4 & 3 4 & 3 & 2 HESA data SLs/Ls) 100%] 100%] 100%] GPA) University of Cambridge 2040.39 32% 39% 24% 4% 1% 2.98 71% 95% 1419 144% 2.98 71% 95% 1 University of Oxford 2245.83 32% 39% 24% 5% 1% 2.96 70% 94% 1434 157% 2.96 70% 94% 2 London School of Economics and Political Science 490.36 35% 34% 25% 6% 1% 2.96 68% 93% 399 123% 2.96 68% 93% 3 University College London 1792.68 27% 39% 27% 6% 1% 2.84 66% 93% 1762 102% 2.84 66% 93% 4 University of Warwick 966.35 21% 44% 29% 6% 0% 2.80 65% 94% 910 106% 2.80 65% 94% 5 University of Edinburgh 1639.81 22% 40% 28% 8% 2% 2.75 63% 91% 1541 106% 2.75 63% 91% 6 University of St Andrews 491.1 19% 40% 34% 6% 0% 2.72 60% 94% 463 106% 2.72 60% 94% 7 University of Bristol 1198.7 18% 43% 31% 7% 0% 2.72 61% 93% 1122 107% 2.72 61% 93% 8 Lancaster University 611.39 19% 42% 31% 8% 0% 2.71 61% 92% 579 106% 2.71 61% 92% 9 University of Durham 759.3 20% 41% 31% 8% 1% 2.72 61% 92% 767 99% 2.69 60% 91% 10 Royal Holloway, University of London 436.17 19% 41% 30% 9% 1% 2.67 60% 90% 434 101% 2.67 60% 90% 11 University of Leeds 1269.66 18% 43% 33% 6% 0% -

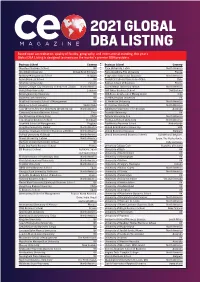

2021 Global Dba Listing

2021 GLOBAL DBA LISTING Based upon accreditation, quality of faculty, geography, and international standing, this year’s Global DBA Listing is designed to showcase the market’s premier DBA providers. Business School Country Business School Country Aberdeen Business School UK Pace University: Lubin North America Abu Dhabi University United Arab Emirates Paris-Dauphine PSL University France Antwerp Management School Belgium Pepperdine University: Graziadio North America Aston Business School UK Pontifical Catholic University of Chile Chile Athabasca University Canada Rennes School of Business France Baruch College, City University of New York: Zicklin North America Sacred Heart University: Welch North America Beirut Arab University Lebanon SBS Swiss Business School Switzerland Birmingham City University UK SDA Bocconi Schoool of Management Italy Bournemouth University UK Sheffield Hallam University UK Bradford University School of Management UK St. Ambrose University North America Business School Lausanne Switzerland St. Thomas University North America Case Western Reserve University: Weatherhead North America Swinburne University of Technology Australia Centrum Graduate Business School Peru Teesside University UK City University of Hong Kong China Temple University: Fox North America Copenhagen Business School Denmark Thomas Jefferson University North America Cranfield School of Management England TiasNimbas Business School Netherlands Creighton University: Heider North America United Arab Emirates University UAE Crummer Graduate School