378 Ecclesiology Reviews 379 Not Individualist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2260Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/4527 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. God and Mrs Thatcher: Religion and Politics in 1980s Britain Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 Liza Filby University of Warwick University ID Number: 0558769 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. ……………………………………………… Date………… 2 Abstract The core theme of this thesis explores the evolving position of religion in the British public realm in the 1980s. Recent scholarship on modern religious history has sought to relocate Britain‟s „secularization moment‟ from the industrialization of the nineteenth century to the social and cultural upheavals of the 1960s. My thesis seeks to add to this debate by examining the way in which the established Church and Christian doctrine continued to play a central role in the politics of the 1980s. More specifically it analyses the conflict between the Conservative party and the once labelled „Tory party at Prayer‟, the Church of England. Both Church and state during this period were at loggerheads, projecting contrasting visions of the Christian underpinnings of the nation‟s political values. The first part of this thesis addresses the established Church. -

Matthew 5 the Sermon on the Mount Part 1 the Blessed

Matthew 5 The Sermon on the Mount Part 1 The Blessed Matthew 4:23 And Jesus went about all Galilee, teaching in their synagogues, and preaching the gospel of the kingdom, and healing all manner of sickness and all manner of disease among the people. You must connect chapter 5 to chapter 4. In the original manuscript, of the bible, there are no chapter or verse numbers. Jesus has started his ministry and is teaching in synagogues and preaching the gospel of the kingdom. What kingdom? The fulfillment of the promise to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. This is known as the millennium kingdom in the book of Revelation. 24 And his fame went throughout all Syria: and they brought unto him all sick people that were taken with divers diseases and torments, and those which were possessed with devils, and those which were lunatick, and those that had the palsy; and he healed them. 25 And there followed him great multitudes of people from Galilee, and from Decapolis, and from Jerusalem, and from Judaea, and from beyond Jordan. Because Jesus is healing the sick, he is famous. People who have ill family members; who have given up on them getting better; now have hope. They are traveling great distances to come to the man of God who miraculously heals all that come. From this, chapter 5 is just a continuation. 1 And seeing the multitudes, he went up into a mountain: and when he was set, his disciples came unto him: 2 And he opened his mouth, and taught them, saying, He sees the multitude, thousands of people seeking hope. -

God in Government: the Impact of Faith on British Politics and Prime Ministers, 1997-2012

GOD IN GOVERNMENT: THE IMPACT OF FAITH ON BRITISH POLITICS AND PRIME MINISTERS, 1997-2012 Zaki Cooper 24 September 2013 Faith & Politics Open Access. Some rights reserved. As the publisher of this work, Demos wants to encourage the circulation of our work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. We therefore have an open access policy which enables anyone to access our content online without charge. Anyone can download, save, perform or distribute this work in any format, including translation, without written permission. This is subject to the terms of the Demos licence found at the back of this publication. Its main conditions are: · Demos and the author(s) are credited · This summary and the address www.demos.co.uk are displayed · The text is not altered and is used in full · The work is not resold · A copy of the work or link to its use online is sent to Demos. You are welcome to ask for permission to use this work for purposes other than those covered by the licence. Demos gratefully acknowledges the work of Creative Commons in inspiring our approach to copyright. To find out more go to www.creativecommons.org Published by Demos 2013 © Demos. Some rights reserved. Third Floor Magdalen House 136 Tooley Street London SE1 2TU T 0845 458 5949 F 020 7367 4201 [email protected] www.demos.co.uk 2 Faith & Politics INTRODUCTION Alistair Campbell famously said, ‘we don’t do God’, but this does not seem to have been borne out by developments in British politics since Labour swept to power in 1997. -

Fall 2010 (.Pdf)

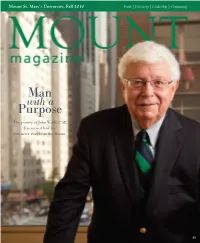

Mount St. Mary’s University, Fall 2010 Faith | Discovery | Leadership | Community Man with a Purpose The journey of John Walsh, C’58, has carried him far, but never away from the Mount. $5 President’s Letter Left: Opening Mass of the Holy Spirit held August 25. Below: Catie Carnes The new academic year could family, her classmates and and account for a life well lived. campus where the four pillars of not have started better. On a faculty needed help and support, We were strongly reminded of faith, discovery, leadership and beautiful Sunday in August, 430 and the campus community the Gospel admonition to “be community provide strength to Dearnew freshmen and theirFriends, parents needed information and a plan prepared, for at an hour you do support us all. arrived and were welcomed by of action. Fortunately, here not expect …” (Luke 12:40). an enthusiastic and skilled team at the Mount we practice for It is my hope that the tragedy of of 150 students, faculty and staff. campus emergencies, expect the In a larger sense, we are Catie’s sudden death will help The Seminary was full, with unexpected and have a quick comforted because, as a our students mature in respect its 166 men already back and and rapid response system in Catholic university, faith is our for their own lives and their into their orientation routine. place. Yet, no matter how much first pillar and the center that relationship with others. So as It is always great to witness the we prepare, the tears still come. brings us together. -

The Religious Mind of Mrs Thatcher

The Religious Mind of Mrs Thatcher Antonio E. Weiss June 2011 The religious mind of Mrs Thatcher 2 ------------------------------------------- ABSTRACT Addressing a significant historical and biographical gap in accounts of the life of Margaret Thatcher, this paper focuses on the formation of Mrs Thatcher’s religious beliefs, their application during her premiership, and the reception of these beliefs. Using the previously unseen sermon notes of her father, Alfred Roberts, as well as the text of three religious sermons Thatcher delivered during her political career and numerous interviews she gave speaking on her faith, this paper suggests that the popular view of Roberts’ religious beliefs have been wide of the mark, and that Thatcher was a deeply religious politician who took many of her moral and religious beliefs from her upbringing. In the conclusion, further areas for research linking Thatcher’s faith and its political implications are suggested. Throughout this paper, hyperlinks are made to the Thatcher Foundation website (www.margaretthatcher.org) where the sermons, speeches, and interviews that Margaret Thatcher gave on her religious beliefs can be found. The religious mind of Mrs Thatcher 3 ------------------------------------------- INTRODUCTION ‘The fundamental reason of being put on earth is so to improve your character that you are fit for the next world.’1 Margaret Thatcher on Today BBC Radio 4 6 June 1987 Every British Prime Minister since the sixties has claimed belief in God. This paper will focus on just one – Margaret Thatcher. In essence, five substantive points are argued here which should markedly alter perceptions of Thatcher in both a biographical and a political sense. -

General Assembly Speech – 2018 Church

General Assembly Speech – 2018 Church and Society Council “Abundance rather than poverty has a legitimacy that derives from the very nature of creation”. Those words formed a part of a speech delivered to this General Assembly 30 years ago by the Prime Minister of the day, Margaret Thatcher. Her argument was that we should not hinder the free market and wealth creation as it serves to lift people out of poverty and create abundance. That beautiful word, abundance, has in many cases been misappropriated by the ideology of unfettered wealth creation for the few, grinding poverty for many and the degradation of the environment on which all of life depends. The “trickle-down” effect of economic policy that the Prime Minister envisaged has actually resulted in a “flood-up” as the rich get richer and the poor increasingly living in the shanties and refugee camps of the world know anything but abundance. 1 Jonathan Raban, responding to the “Sermon on the Mound” gave a telling response when he wrote that “abundance is not the Biblical alternative to poverty, sufficiency is”. In the words of Fritz Schumacher, we have a system of economics that “ravages nature and brutalizes people”. He also said, in his prophetic work, Small is Beautiful that Jesus’s words, “seek ye first the kingdom of God” contain a threat, that “unless you seek first the kingdom, these other things, which you also need, will cease to be available to you.” The time is right to embrace a theology of “sufficiency” and begin more closely to align our actions and priorities with our Kingdom values. -

The Life I Now Live in the Flesh I Live by Faith in the Son of God, Who Loved

OPEN GYM Thursday, April 19, 6:00-7:00 pm. Come enjoy the gym with your family! All ages (baby to April 8-15, 2018 100+) can come out and play basketball, ride scooters and run free. An adult must attend with any SUNDAY, April 8 TUESDAY, April 10 FRIDAY, April 13 child 11 and under. 9:00 am Adult Education Class 10:00 am Staff Meeting 8:00 am Women’s Exercise 9:15 am New Spirit Ringers 10:15 am Tai Chi Class ATTENTION ALL GARDNERS! Valley youth are SATURDAY, April 14 9:15 am Sanctuary Choir 11:00 am Women’s Bible Study offering a spring plant sale this month to benefit the 9:00 am Scout Training Mtg. The life I now live in the flesh 9:30 am Early Bird Coffee 5:30 pm Program Staff Mtg. youth mission fund. Please stop by the table upstairs 9:30 am Special Session Mtg. 6:00 pm Bear Den Meeting SUNDAY, April 15 during coffee fellowship to pick up an order form. 10:00 am Worship 6:30 pm Cub Scouts 9:00 am Adult Education Class I live by faith in the Son of God, Annuals, herbs, vegetables, and hanging baskets 10:20 am Sunday Funday 7:00 pm Session 9:15 am New Spirit Ringers from New Leaf Nursery are available. Plants 11:00 am Coffee Fellowship 9:15 am Sanctuary Choir WEDNESDAY, April 11 available for pick up on May 19 from 3-5 pm in the 11:30 am Communication Mtg. 9:30 am Early Bird Coffee 8:00 am Men’s Bible Study who loved me and gave himself for me. -

Grade Specific Religious Education Curriculum

Grade Specific Religious Education Curriculum Archdiocese of Milwaukee Office for Schools, Child, and Youth Ministries and Holy Apostles School Scripture Liturgy/Sacrament/Prayer Historical/Creedal/Church Moral Life Life Experiences Family Life Archdiocese of Milwaukee Adopted: August, 1997 Updated: August, 2002 Forward The Apostles Creed I believe in God, the Father almighty, creator of heaven and earth. I believe in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord. He was conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary. He suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried. He descended to the dead. On the third day he rose again. He ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right of the Father. He will come again to judge the living and the dead. I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic Church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting, Amen. Love the holy Scriptures and wisdom, will love you. Love wisdom, and she will keep you safe. Honor wisdom, and she will embrace you. St. Jerome A - 1 Table of Contents Forward A - 1 Table of Contents A - 2 Philosophy Statement A - 3 National Catechetical Directory B 1 Archdiocese of Milwaukee Grade Level Exit Expectations C - 1 Religious Education Exit Expectations Assessment Checklists D - 1 Sample Student Assessment Information E - 1 Resources F - 1 Student Resources (Incomplete) Assessment Resources (Incomplete) Teacher Resources Religious Education Organizations (Incomplete) Family Life (Incomplete) G - 1 A - 2 Philosophy Catholic education is an expression of the mission entrusted by Jesus to the Church He founded. -

The Effect of Thatcherism on Nationalist Movements in the United

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The Bulldog and the Thistle: The Effect of Thatcherism on Nationalist Movements in the United Kingdom A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science by Isabella Christina Gabrovsky Committee in charge: Professor Benjamin J. Cohen, Chair Professor Amit Ahuja Professor Bridget L. Coggins Professor Michael Kyle Thompson, Pittsburg State University September 2017 The thesis of Isabella Christina Gabrovsky is approved. ______________________________________________ Amit Ahuja _____________________________________________ Bridget L. Coggins ____________________________________________ Michael Kyle Thompson ____________________________________________ Benjamin J. Cohen, Chair August 2017 The Bulldog and the Thistle: The Effect of Thatcherism on Nationalist Movements in the United Kingdom Copyright © 2017 by Isabella Christina Gabrovsky iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all the people who have helped me during the writing process. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Committee Chair and Academic Advisor, Professor Benjamin J. Cohen, for his constant support and guidance. I would also like to thank the members of my committee, Professors Amit Ahuja, Bridget Coggins, and Michael Kyle Thompson for their advice and edits. Finally, I would like to acknowledge my family for their unconditional love and support as I completed this thesis. iv ABSTRACT The Bulldog and the Thistle: The Effect of Thatcherism on Nationalist Movements in the United Kingdom by Isabella Christina Gabrovsky The purpose of this thesis is to explain the origins of the new wave of nationalism in the United Kingdom, particularly in Scotland. The popular narrative has been to blame Margaret Thatcher for minority nationalism in the UK as nationalist political parties became more popular during and after her tenure as Prime Minister. -

Brown Reveals Global Moral Vision

BBC NEWS | UK | Scotland | Brown reveals global moral vision http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/scotland/7405547.stm Low graphics Help Search Explore the BBC BBC NEWS CHANNEL News Front Page Page last updated at 10:58 GMT, Saturday, 17 May 2008 11:58 UK E-mail this to a friend Printable version Brown reveals global moral vision Africa Americas SEE ALSO Asia-Pacific Burma 'guilty of inhuman action' Europe 17 May 08 | UK Politics Middle East New moderator sworn into office South Asia 15 May 08 | Scotland UK I can save economy again - Brown England 15 May 08 | UK Politics Northern Ireland Sermon on the Mound Scotland 16 May 08 | The Westminster Hour Wales RELATED BBC LINKS UK Politics Church of Scotland Education Scottish politics Magazine Business RELATED INTERNET LINKS Church of Scotland Health Downing Street website Science & Environment Technology The BBC is not responsible for the content of external internet sites Entertainment Also in the news TOP SCOTLAND STORIES ----------------- Video and Audio Claims row MP cannot stand again ----------------- Pair jailed for festival stabbing Have Your Say Attacker jailed over knife in eye In Pictures | News feeds Country Profiles Special Reports MOST POPULAR STORIES NOW Related BBC sites SHARED READ WATCHED/LISTENED Sport Weather 'Mass opposition rally' in Tehran On This Day Editors' Blog BA asks staff to work for nothing BBC World Service Sarkozy jeered at Bongo's funeral Nuclear N Korea is 'grave threat' Captain America alter-ego returns Day in pictures Letterman sorry over Palin joke Hydrogen car to be 'open source' Grandfather reveals lottery joy Postcard from Somali pirate capital The prime minister urged nations and religions to act together to solve problems Most popular now, in detail Gordon Brown has been setting out his vision for a global society governed by a shared "moral sense". -

April 22 – John D

Valley Community Presbyterian Church April 2018 Sundays at Valley Children’s Spring Musical April 29 The King’s Kids Choir will present the musical Adult Education Class, 9:00 a.m. Sermon on the Mound in worship on Sunday, April Early Coffee in Library, 9:30 a.m. 29. This musical, created by Celeste Clydesdale, Worship, 10:00 a.m. combines valuable life lessons with catchy songs and Sunday Funday, 10:20 a.m. a baseball theme. Sermon on the Mound centers on spring training for the Eagles baseball team. Mac Coffee Fellowship, 11:00 a.m. Wire, the rookie, has been training with the team for April forty days and forty nights and is nervous about the opening game. He remembers to follow God as his head coach and to work 1 Easter Sunday Worship, together as a team to live out God’s word. Will he hit a home run? You’ll have 8:00 and 10:00 a.m. to come and find out on April 29! Easter Egg Hunt, 9:00 a.m. in the Youth House Spring Fundraisers to Benefit Youth 8 Communion Mission Reception of New Members, This year our middle school and high school youth have two events in April during 10:00 a.m. worship to help raise money for their summer mission trips. 15 Membership Class, April 29 Pancake Breakfast 11:15 a.m. First, the annual pancake breakfast will be held in Davis Hall on April 29. Dining for Women, 11:30 a.m. Congregants will be able to enjoy a delicious breakfast before worship from 9:00-10:00 a.m. -

Amy Grant Returns to Hoover

Week 2: June 22-28, 2019 Amy Grant returns to Hoover 8:15 p.m., Hoover Auditorium Saturday, June 22 Grammy and Dove Award-winning singer and songwriter Amy Grant returns to Lakeside to perform her timeless hits, “Baby, Baby,” “El Shaddai” and “Every Heartbeat.” Ever since she burst onto the scene as a fresh-faced teenager, bringing contemporary Tennis Clinic with JoAnne Russell Christian music to the Lakeside Chautauqua welcomes for- of Fame. forefront of American mer Wimbledon Ladies Doubles winner Russell also served as an Assistant culture, the Nashville JoAnne Russell to lead a Tennis Clin- Coach at the University of Illinois from native has gained a ic until June 23 at the Williams Tennis 1998-2005. Now retired, she is a tennis reputation for creating Campus. Register at lakesideohio.com/ pro at Grey Oaks Country Club in Na- Christian music singer of all time, earning songs that examine life’s tennisclinic. ples, Fla. complexities with an open heart. six Grammys, 22 Dove Awards and three Sessions will be set up in 60-minute Steve Vaughn, an elite professional She became the first Christian music multi-Platinum albums. to 90-minute timeslots and organized tennis player, will teach alongside Rus- artist to have a platinum record and went Ten of her singles have reached the Top according to skill level. Players should sell at the clinic. on to become a crossover sensation, arrive 15 minutes prior to their session. 40 for pop, and 17 have become Top 40 Vaughn has played tennis his entire her musical gifts transcending genre Russell is an American former pro- hits for adult contemporary.