A Study of Newsworkers As Agents Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USA, the World Is Watching: Mass Violations by U.S. Police of Black

USA: THE WORLD IS WATCHING MASS VIOLATIONS BY U.S. POLICE OF BLACK LIVES MATTER PROTESTERS’ RIGHTS Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: A line of Minnesota State Patrol officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Victor J. Blue https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AMR 51/2807/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS TITLE PAGE ABREVIATIONS 4 TERMINOLOGY 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 KEY RECOMMENDATIONS 6 METHODOLOGY 8 POLICE USE OF DEADLY FORCE 9 FAILURE TO TRACK HOW MANY PEOPLE ARE KILLED BY POLICE IN THE USA 12 DISCRIMINATORY POLICING AND THE DISPROPORTIONATE IMPACT -

68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A

Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Professer C. Greig Crysler Professor Richard Walker Summer 2015 Sagan Copyright page Sagan Abstract Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Political protest is an increasingly frequent occurrence in urban public space. During times of protest, the use of urban space transforms according to special regulatory circumstances and dictates. The reorganization of economic relationships under neoliberalism carries with it changes in the regulation of urban space. Environmental design is part of the toolkit of protest control. Existing literature on the interrelation of protest, policing, and urban space can be broken down into four general categories: radical politics, criminological, technocratic, and technical- professional. Each of these bodies of literature problematizes core ideas of crowds, space, and protest differently. This leads to entirely different philosophical and methodological approaches to protests from different parties and agencies. This paper approaches protest, policing, and urban space using a critical-theoretical methodology coupled with person-environment relations methods. This paper examines political protest at American Presidential National Conventions. Using genealogical-historical analysis and discourse analysis, this paper examines two historical protest event-sites to develop baselines for comparison: Chicago 1968 and Dallas 1984. Two contemporary protest event-sites are examined using direct observation and discourse analysis: Denver 2008 and St. -

Chapter 30.Pdf

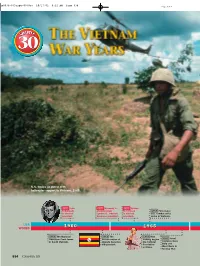

p0934-935aspe-0830co 10/17/02 9:22 AM Page 934 U.S. troops on patrol with helicopter support in Vietnam, 1965. 1960 John 1963 Kennedy is 1964 Lyndon F. Kennedy assassinated; B. Johnson 1965 First major is elected Lyndon B. Johnson is elected U.S. combat units president. becomes president. president. arrive in Vietnam. USA 1960 WORLD 1960 19651965 1960 The National 1962 The 1966 Mao Liberation Front forms African nation of Zedong begins 1967 Israel in South Vietnam. Uganda becomes the Cultural captures Gaza independent. Revolution Strip and in China. West Bank in Six-Day War. 934 CHAPTER 30 p0934-935aspe-0830co 10/17/02 9:22 AM Page 935 INTERACTINTERACT WITH HISTORY In 1965, America’s fight against com- munism has spread to Southeast Asia, where the United States is becoming increasingly involved in another country’s civil war. Unable to claim victory, U.S. generals call for an increase in the number of combat troops. Facing a shortage of volunteers, the president implements a draft. Who should be exempt from the draft? Examine the Issues • Should people who believe the war is wrong be forced to fight? • Should people with special skills be exempt? • How can a draft be made fair? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 30 links for more information about The Vietnam War Years. 1968 Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy are 1970 Ohio 1973 United assassinated. National 1969 States signs Guard kills 1968 Richard U.S. troops 1972 cease-fire four students M. Nixon is begin their Richard M. with North 1974 Gerald R. -

FELLOWSHIPS for INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS 2014 the Greater Milwaukee Foundation’S Mary L

The Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Mary L. Nohl Fund FELLOWSHIPS FOR INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS 2014 The Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Mary L. Nohl Fund FELLOWSHIPS FOR INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS 2014 The Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Mary L. Nohl Fund FELLOWSHIPS FOR INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS 2014 Anne KINGSBURY Shana McCAW & Brent BUDSBERG John RIEPENHOFF Emily BELKNAP Jenna KNAPP Erik LJUNG Kyle SEIS OCTOBER 9, 2015-JANUARY 9, 2016 INOVA (INSTITUTE OF VISUAL ARTS) 2155 NORTH PROSPECT AVENUE MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN 53202 For a century, the Greater Milwaukee Foundation has helped individuals, families and organizations realize their philanthropic goals and make a difference in the community, during their lifetimes and EDITOR’S for future generations. The Foundation consists of more than 1,200 individual charitable funds, each created by donors to serve the charitable causes of their choice. The Foundation also deploys both PREFACE human and financial resources to address the most critical needs of the community and ensure the vitality of the region. Established in 1915, the Foundation was one of the first community foundations in the world. Ending 2014 with more than $841 million in assets, it is also among the largest. In 2003, when the Greater Milwaukee Foundation decided to use a portion of a bequest from artist Mary L. Nohl to underwrite a fellowship program for individual visual artists, it made a major investment in local artists who traditionally lacked access to support. The program, the Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Mary The Greater Milwaukee Foundation L. Nohl Fund Fellowships for Individual Artists, provides unrestricted awards to artists to create new work or 101 West Pleasant Street complete work in progress and is open to practicing artists residing in Milwaukee, Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Milwaukee, WI 53212 Washington counties. -

Occupy-Gazette-3.Pdf

Sarah Resnick ANN SNITOW Nov. 15 page 7 Greenham Common Courtroom page 20 Geoffrey Wildanger Kathryn Crim page 30 Kathleen Ross page 14 OCCUPY UC DAVIS Bulldozers of the Arrested! page 14 Mind OCCUPY!#3 An OWS-Inspired Gazette Daniel Marcus page 30 Marco Roth Occupation to Mayor Communization Bloomberg’s page 32 SIlvia Federici Language page 2 CHRISTOPHER HERRING AND ZOLTAN GLUCK page 22 Women, Re-Articulating the Struggle for Education Austerity, Marina Sitrin page 30 and the Some unfinished issues with feminist horizon- revolution talism Nicholas Mirzoeff page 32 Eli Schmitt page 18 Mark Greif page 2 COMPLETE TABLE OF CONTENTS Occupy Climate The best Years Open Letter INSIDE THE BACK COVER Change! of our lives ZUCCOTTI RAID & AFTER they were outnumbered, easily, two to “Police—protect—the 1 per-cent.” You a life of qualities? Is quality, by definition one. were standing, twenty of you, defending immeasurable, only describable, some- “What are they so afraid of?” my com- an empty street with bank skyscrapers thing that can be charted by the cleanli- Astra Taylor panion asked when we first arrived at Wall rising out of it. You don’t belong in those ness of a street, the absence of certain Street just after 1 AM, and as I watched skyscrapers. You knew it too. smells, certain people? Is the absence of the eviction this excessive use of force the question dirt, smells, noise, and people what the kept ringing in my ears. But the answer is mayor means by “thriving?” Is there really Last night, in what seems to be part of a obvious: they are afraid of us. -

Within Temptation Ft. Piotr Rogucki - Whole World Is Watching

antyteksty.com - teksty, które coś znaczą Dominika Bona Within Temptation ft. Piotr Rogucki - Whole World Is Watching Within Temptation ft. Piotr Rogucki - Whole World Is Watching Utwór ‘’Whole world is watching” pochodzi z albumu Within Temptation “Hydra”. Tele- dysk z gościnnym udziałem Piotra Roguckiego, wokalisty Comy, po raz pierwszy ukazał się w sieci 28 stycznia 2014r. Piosenka jest również dostępna w drugiej wersji z udziałem Davida Pirnera, wokalisty zespołu Soul Asylum. Teledysk mówi nam o niezwykłej sile ducha oraz o przekraczaniu swoich granic, wznoszeniu się coraz wyżej. Sharon den Adel, wokalistka Within Temptation tak opowiada o współpracy z Piotrem Roguckim: „Gdy napisaliśmy utwór Whole World Is Watching czuliśmy, że dobrze by w nim zabrzmiał fajny, moc- ny męski głos. Pełen energii, ale również emocji głos Piotra idealnie pasował do tego kawałka, dlate- go jesteśmy niezmiernie zadowoleni z efektu.” Piotr Rogucki dodaje: „Utwór Whole World Is Watching to brzmienie niezwykłej przygody: ogromny zaszczyt niespodziewanego zaproszenia, owocna współpraca, a efektem tego wszystkiego jest połą- czenie dwóch jakże różnych głosów w jednej, pięknej piosence. Mam nadzieję, że ten kawałek będzie równie ważny dla słuchaczy tak, jak bez wątpienia, jest dla mnie.” Tekst piosenki Within Temptation ft. Piotr Rogucki Tłumaczenie Within Temptation ft. Piotr Rogucki — Whole World Is Watching — Whole World Is Watching You live your life Żyjesz swoim życiem You go day by day like nothing can go wrong Idziesz dzień za dniem jakby nic nie mogło -

'The Whole World Is Watching . You'.;·•Ixon

MAY 19, 1972 25 CENTS VOLUME 36/NUMBER-19 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE --- 'The whOle world is watching .yoU'.;·•ixon "4 The following statement was issued by Linda Jenness, So stop Nixon and end the war. The goal of the antiwar move cialist Workers Party candidate for president. ment should be to involve the massive numbers of anti war Americans in protest action. And we can only do this When President Nixon went on TV May 8 to announce if we go out into neighborhoods, shopping centers, schools, his decision to seal off North VIetnam's supply routes and work places, and military bases, passing out leaflets, placing to launch all-out genocidal bombing' of both the North and . ads in newspapers, talking to people,. and organizing dem- South, he made a special plea to the American people to support him in this bloody escalation. He said u It is you, most of all, that the world will be watching." The world is watching the American people-to see whether United actions called NEW YORK CITY, May· 10-The National Peace Action Coalition we will allow Nixon to get away with this dangerous new and the People's Coalition for Peace and Justice decided at a meeting escalation that contains within it the possibility of world here today to join forces in calling for a massive march and rally war and nuclear destruction. against the war in Washington, D. C., on Sunday, May 21, and for On the very night of Nixon's speech, and on the following sustained antiwar action in Washington and around the country after days, students and others spontaneously took to the streets that date. -

Download the SUPERSTITIOUS ISSUE (PDF)

Smart Partners 2010-2011 Adnan Ahmed ......................................Dylan Dawson Doris Alcantara ................................ Katherine Brown Michael Bannister .................................... Jason Hare Richard Brea........................................... Shane West Elena Caballero .....................................J McLoughlin Smart Partners is the educational mentoring Enrique Caballero ............................Jeremy Keaveny program of The 52nd Street Project. Natalia Caballero ...................................Katie Flahive Fivey is the program’s literary magazine. Samantha Caldona ................................Laura Konsin Eric Carrero ...........................................Brian Hastert the 52nd street project Nick Carrero .................................... Armando Riesco board of directors Gabriella DeJesus ..............................Livia De Paolis Lisa Benavides Willie Reale, Alvin Garcia ..........................................Graeme Gillis Rachel Chanoff founder Jason Gil.............................................. Sean Kenealy Cathy Dantchik Gus Rogerson Diamond Deanna Graves ...............Alexandra O’Daly Carolyn DeSena Shirley Rumierk, Jasmine Hernandez................................... Tory Dube Wendy Ettinger, alumni member Rafael Irizarry, III ................................George Babiak chair emeritus José Soto, Jr., Maximo Jimenez....................................John Sheehy Louis P. Friedman alumni member Kamil Kuzminski ...................................... Rory Scholl -

Analyzing Style and Meaning in the Music of Abbey Lincoln, Nina Simone and Cassandra Wilson

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2012 Learning How to Listen': Analyzing Style and Meaning in the Music of Abbey Lincoln, Nina Simone and Cassandra Wilson LaShonda Katrice Barnett College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Barnett, LaShonda Katrice, "Learning How to Listen': Analyzing Style and Meaning in the Music of Abbey Lincoln, Nina Simone and Cassandra Wilson" (2012). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623358. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-fqh4-zq06 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'Learning How To Listen': Analyzing Style and Meaning in the Music of Abbey Lincoln, Nina Simone and Cassandra Wilson LaShonda Katrice Barnett Park Forest, Illinois, U.S.A. Master of Arts, Sarah Lawrence College, 1998 Bachelor of Arts, University of Missouri, 1995 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College ofWilliam and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College ofWilliam and Mary August, 20 12 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation -

Selected Speeches of President George W. Bush, 2001

Selected Speeches of President George W. Bush 2001 – 2008 SELECTED SPEECHES OF PRESIDENT GEORGE W. B USH 2001 – 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2001 The First Inaugural Address January 20, 2001 ............................................................................ 1 Remarks to New White House Staff January 22, 2001 ............................................................................ 7 Remarks on the Education Plan Submitted to Congress January 23, 2001 ............................................................................ 9 Faith-Based and Community Initiatives Announcement January 29, 2001 .......................................................................... 15 Remarks at the National Prayer Breakfast February 1, 2001 .......................................................................... 19 Address to the Joint Session of the 107th Congress February 27, 2001 ........................................................................ 23 Dedication of the Pope John Paul II Cultural Center March 22, 2001 .............................................................................37 Tax Relief Address to the United States Chamber of Commerce April 16, 2001 ............................................................................... 41 Days of Remembrance Observance April 19, 2001 ............................................................................... 47 Stem Cell Address to the Nation August 9, 2001 .............................................................................. 51 Address to the Nation on the -

Look out Haskell It's Real Transcript

“Look out Haskell, it’s real!” The Making of Paul Cronin DIALOGUE TRANSCRIPT www.lookouthaskell.com © Sticking Place Films 2001 (revised 2015) Cast of characters in alphabetical order Muhal Richard Abrams – musician Michael Arlen – journalist Bill Ayers – antiwar activist Carroll Ballard – cameraman Peter Bart – Paramount Pictures James Baughman – historian Peter Biskind – historian Verna Bloom – actor Peter Bonerz – actor Alan Brinkley – historian Edward Burke – Chicago police Michael Butler – screenwriter Ray Carney – historian Jack Couffer – novelist Ian Christie – film historian Jay Cocks – critic Andrew Davis – filmmaker David Dellinger – activist Bernard Dick – historian Bernadine Dohrn – antiwar activist Jeff Donaldson – actor/artist General Richard Dunn – Illinois National Guard Roger Ebert – film critic Linn Ehrlich – photographer David Farber – historian Richard Flacks – activist Robert Forster – actor Reuven Frank – TV news executive Bill Frapolly – Chicago police Todd Gitlin – activist Paul Golding – editors Mark Goodall – historian Terrence Gordon – Marshall McLuhan scholar Mike Gray – cameraman Dick Gregory – activist Roger Guy – sociologist Duane Hall – photographer Dan Hallin – historian Tom Hayden – activist Jonathan Haze – production coordinator Neil Hickey – journalist www.lookouthaskell.com 2 Thomas Jackson – historian Tom Keenan – student reporter Douglas Kellner – media theorist Peter Kuttner – cameraman Paul Levinson – media theorist J. Fred MacDonald - historian Philip Marchand – Marshall McLuhan biographer Michael -

Print Media and the 1968 Democratic National Convention

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2001 Blood sweat and gas: Print media and the 1968 Democratic National Convention Sarah Switzer Love The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Love, Sarah Switzer, "Blood sweat and gas: Print media and the 1968 Democratic National Convention" (2001). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5066. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5066 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. '*Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission X No, I do not grant permission________ Author's Signature: ida a h ^ d iM Date: S ' / ? ” • 6 1 Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 Blood, Sweat and Gas: Print Media and the 1968 Democratic National Convention by Sarah Switzer Love B.A., Sociology, University of Wisconsin Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 2001 Approved by - r ~ ------ r2--- Chairperson Dean of the Graduate School 5~-2S-o| Date UMI Number: EP40530 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.