Richard Dillon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Color Foba Clrv2.Indd

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Baker, Barry and Cronkhite Historic District Marin County, California Cultural Landscape Report for Fort Baker Golden Gate National Recreation Area Cultural Landscape Report for Fort Baker Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Baker, Barry and Cronkhite Historic District Marin County, California July 2005 Acknowledgements Special thanks to Ric Borjes and Randy Biallas for getting this project underway. Project Team Pacific West Region Office - Seattle Cathy Gilbert Michael Hankinson Amy Hoke Erica Owens Golden Gate National Recreation Area Barbara Judy Jessica Shors Pacific West Region Office - Oakland Kimball Koch Len Warner Acknowledgements The following individuals contributed to this CLR: Golden Gate National Recreation Area Mai-Liis Bartling Stephen Haller Daphne Hatch Nancy Horner Steve Kasierski Diane Nicholson Nick Weeks Melanie Wollenweber Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy Erin Heimbinder John Skibbe Betty Young Golden Gate National Recreation Area Leo Barker Hans Barnaal Kristin Baron Alex Naar Marin Conservation Corp Francis Taroc PacificWest Region Office - Oakland Shaun Provencher Nelson Siefkin Robin Wills Presidio Trust Peter Ehrlich Ben Jones Michael Lamb Table of Contents Table of Contents Acknowledgements List of Figures .................................................................................................................................iii Introduction Management Summary ................................................................................................................. -

Mill Valley Air Force Station East Is-Ridgecrest Boulevard, Mount Tarua.Lpais Mill Valley Vicinity .Marin County Califomia

Mill Valley Air Force Station HABS No. CA-2615 East iS-Ridgecrest Boulevard, Mount Tarua.lpais Mill Valley Vicinity .Marin County califomia PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service Western Region Department of the Interior San Francisco, California 94107 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDING SURVEY MILL VALLEY AIR FORCE STATION HABS No. CA-2615 Location: On the summit of Mount Tamalpais in Marin County, California Off of California State Highway 1 on East Ridg~~rest Boulevard. West of Mill Valley, California. North of San Francisco, California. Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: 10.535320.4197 420 10.535000.4197000 I 0.534540.4196680 10.534580.4197000 10.535000.4197260 Present Owner: National Park Service leases the land from the Marin Municipal Water District. Present Occupant: Mostly vacant except for the operations area which is occupied by the Federal Aviation Administration Facility Present Use: Federal Aviation Administration Facility Significance: Mill Valley Air Force Station (MVAFS) played a significant role in the United States Air Defense system during the period of the Cold War. The threat of Soviet nuclear and air force power warranted the construction of early warning radar stations throughout the country. With the opening of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent end to the Cold War, retrospective scholarship has labeled contributing defense systems, such as early warning radar, important features of United States military history. In fact, America's first major construction project as a result of Cold War hostilities was, apparently, the system of early warning radar stations of which Mill Valley Air Force Station was one. -

Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

PRESIDIO OF SAN FRANCISCO, AAA BATTALION HABS CA-2919 HEADQUARTERS FACILITY ADMINISTRATION BUILDING HABS CA-2919 (Building 1648) Golden Gate National Recreation Area Langdon Court, east of Battery Godfrey San Francisco San Francisco County California PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY PACIFIC WEST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 333 Bush Street San Francisco, CA 94104 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY PRESIDIO OF SAN FRANCISCO, AAA BATTALION HEADQUARTERS FACILITY ADMINISTRATION BUILDING (Building 1648) HABS No. CA-2919 Location: Langdon Court, in the northwest quadrant of the Presidio of San Francisco; approximately 600’ east of Pacific Ocean; San Francisco San Francisco County, California USGS San Francisco North Quadrangle; Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: 4184141 (north), 546035 (east) Present Owner: Golden Gate National Recreation Area National Park Service Present Use: vacant Significance: In 1957, the U.S. Army constructed this utilitarian, one-story, concrete block rectangular building for the 740th Antiaircraft (AAA) Battalion Headquarters, a group that oversaw operations for the Presidio’s Nike missile operations at Battery Caulfield. In 1974, the army remodeled the building for its new tenant, the 902nd Military Intelligence Group of the U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command. Part I. HISTORICAL INFORMATION A. Physical History 1. Dates of Erection: The U.S. Army constructed this building in 1957. 2. Architect: The architect for this building was Corlett & Dewell, Architects and Engineers, 847 Clay Street, San Francisco, CA in coordination with the Army Corp of Engineers. PRESIDIO OF SAN FRANCISCO, AAA BATTALION HEADQUARTERS FACILITY ADMINISTRATION BUILDING HABS No. -

Fort Baker History Walk Horseshoe Cove: a Water Haven on San Francisco Bay Bay Area Discovery Museum

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Baker Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Baker History Walk Horseshoe Cove: A Water Haven on San Francisco Bay Bay Area Discovery Museum Fort Baker Cantonment Battery Cavallo tempo rary w ater fron t ro ad Travis Sailing Center U.S. Coast Guard Station BLDG 670 Road Sa tte 679 rl Sommerville ee R o a 6 7 d Horseshoe Cove M Bldg 633 Boat House a r Battery 1 i Marine Railway n BLDG a Yates 410 R o a d d a o R U.S. Coast Guard Wharf e r o o M 5 BLDG 411 BLDG 8 412 eakwater 4 Satterlee Br 3 2 Public Wharf FORT BAKER Lime Point Fog Signal Station Sausalito, CA indicates the direction you should look for this stop. 2 Fort Baker History Walk: Horseshoe Cove Printed on recycled paper using soy-based inks Horseshoe Cove, with its naturally protected shape and location, has long offered respite from strong winds and currents at the Golden Gate. Native Americans found shelter and an excellent food source here, and later, ships discovered a safe harbor during bad weather. Horseshoe Cove played an important role in the San Francisco military defense system and today provides a quiet refuge from the busy San Francisco Bay’s busy water traffic. The Route Length: 1/2-mile Number of stops: 8 Time required: About 45 minutes Access: The route is flat but only partially paved; some surfaces are uneven and not wheelchair accessible. Portable toilets: Toilets are located next to the the fishing pier, at the edge of the waterfront. -

This Year Marks the Parks Conservancy's 25Th Year, and We

This year marks the Parks Conservancy’s 25th year, and we are very excited to celebrate this significant milestone—a quarter century of supporting these national parks. Together with our public agency partners, the National Park Service and the Presidio Trust, we have collaborated across the Golden Gate National Parks to ensure these treasured places are enjoyed in the present and preserved for the future. Whether a new park bench, a restored trail, a landscape rejuvenated with native plants, the restoration of Crissy Field, or the ongoing transformation of the Presidio from former military post to national park for all, the Parks Conservancy’s achievements have lasting benefits for the natural places and historic landmarks on our doorstep. Our accomplishments result from diligent efforts to connect people to the parks in meaningful ways. We have record numbers of volunteers involved in the parks, innovative and inspiring youth programs at Crissy Field Center and beyond, and unique opportunities for locals and visitors to experience the fascinating history and majestic beauty of these places. Most importantly, we have established a dedicated community of members, donors, volunteers, and friends—people who are invested in the future of our parks. With your support, we contributed more than $10 million in aid to the parks this year. Our cumulative support over 25 years now exceeds $100 million—one of the highest levels of support provided by a nonprofit park partner to a national park in the United States. On this 25th anniversary, we extend our warmest thanks to everyone who has helped us along the way. -

The Efficiency and Effectiveness Task Force

FINAL REPORT The Efficiency and Effectiveness Task Force of the Marin Coun ty School Districts March 2011 March 2011 http://www.marinschools.org/EfficiencyEffectiveness.htm Committee Members Bruce Abbott, Co-Chair, Trustee, Dixie School District Valerie Pitts, Co-Chair, Superintendent, Larkspur School District Debra Bradley, Superintendent, Sausalito Marin City School District Debbie Butler, Trustee, Novato Unified School District Larry Enos, Superintendent, Bolinas-Stinson Union and Lagunitas School Districts David Hellman, Member, Marin County Board of Education Steve Herzog, Superintendent, Reed Union School District Linda M. Jackson, Trustee, San Rafael Elementary and High School Districts Laurie Kimbrel, Superintendent, Tamalpais Union High School District Karen Maloney, Assistant Superintendent, Marin County Office of Education Susan Markx, Deputy Superintendent, Marin County Office of Education Marilyn Nemzer, Member, Marin County Board of Education Mary Jo Pettegrew, Superintendent, Kentfield School District Stephen Rosenthal, Superintendent, Shoreline Unified and Nicasio School Districts Susan Schmidt, Trustee, Tamalpais Union High School District It is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.” Charles Darwin Table of Contents Executive Summary Page 1 Formation of the Task Force Page 2 Purpose Statement Page 2 History of School Districts in Marin County Page 3 Focus on Shared Services Page 5 Task Force Research Summary Page 5 Recommendations Page 10 Next Steps Page 11 Appendix A: Timeline Appendix A Appendix B: Shared Services by District Appendix B Executive Summary In fall 2009, a group of superintendents and school board trustees came together with the support of the Marin County Office of Education to review potential FINAL opportunities to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the public school districts REPORT in Marin. -

Fort Barry Balloon Hangar and Motor Vehicle Sheds Abbreviated Historic Structures Report Fort Barry Balloon Hangar, 1939

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Golden Gate National Recreation Area San Francisco, CA 94123 Fort Barry Balloon Hangar and Motor Vehicle Sheds Abbreviated Historic Structures Report Fort Barry Balloon Hangar, 1939. (PARC, GOGA 32423) Cover Photo: Fort Barry Balloon Han- gar and Motor Vehicle Sheds, 2004. (John Martini) Fort Barry Balloon Hangar and Motor Vehicle Sheds Abbreviated Historic Structures Report Golden Gate National Recreation Area San Francisco, California Produced by the Cultural Resources and Museum Management Division National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC Contents Introduction 7 Preparation 7 Relevant Documents 7 Executive Summary 7 Historic Significance 8 World War I and 1920s 8 World War II Era 11 Nike Missile Era 12 Presidio Riding Stables 12 Evaluation Criteria 13 Balloon Hangar 13 Vehicle Sheds 13 Developmental Timeline 15 Developmental History 17 Pre-Hangar Era 17 Balloon Hangar Era 17 Coast Artillery Use 20 Post-War and Cold War Eras 21 Riding Stable Era 25 Physical Description - Balloon Hangar 28 Exterior 28 Foundation 28 Structure 28 Wall Surfaces 28 Roofing 28 Interior 29 Floor 29 Walls 29 Mechanical and Plumbing 29 Physical Description - Motor Vehicle Sheds 30 Structure 30 Roofing 30 Siding 30 Significant Features 32 Bibliography 33 Appendix A Structural Evaluation of Balloon Hangar Architectural Evaluation of Balloon Hangar Cost Estimate - Balloon Hangar Fort Barry Balloon Hangar and Motor Vehicle Sheds, 2004. (John Martini) 6 Balloon Hangar Historic Structures Report Introduction This Abbreviated Historic Structure Report was prepared by the National Park Service (NPS), Division of Cultural Resources and Museum Management (CRMM), Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA). -

National Park Service Sites Visited — Mark Eberle

National Park Service Sites Visited — Mark Eberle 422 units + DC sites, some with multiple subunits (excluding National Heritage Areas and National Heritage Corridors) Updated 26 May 2018 40 of 57 National Parks visited (highlighted in yellow) All NPS sites accessible to the public visited in 22 states Number of sites visited (in parentheses) might not include all subunits and excludes trails, scenic rivers, and recreation areas. Arkansas (6) Iowa (2) Missouri (5) New Mexico (15) South Dakota (5) Colorado (10) Kansas (5) Montana (7) North Dakota (3) Texas (11) Idaho (6) Louisiana (4) Nebraska (3) Oklahoma (2) Wisconsin (1) Illinois (2) Minnesota (3) Nevada (3) Oregon (4) Wyoming (5) Indiana (3) Mississippi (6) Only a few NPS sites open to the public remain to be visited in 17 states Number of sites visited + number remaining (in parentheses) excludes trails, scenic rivers, and recreation areas. Arizona (19+1) Kentucky (2+1) New Hampshire (0+1) Rhode Island (0+3) Utah (9+3) Connecticut (0+1) Maine (1+3) New Jersey (1+4) South Carolina (2+4) Vermont (0+1) Delaware (0+1) Michigan (4+1) Ohio (4+6) Tennessee (6+3) Washington (5+6) Hawaii (3+4) West Virginia (1+1) 1) Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historical Park, Kentucky a) Abraham Lincoln Birthplace b) Abraham Lincoln Boyhood Home 2) Acadia National Park, Maine 3) Adams National Historical Park, Massachusetts 4) African Burial Ground National Monument, New York 5) Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska 6) Ala Kahakai National Historical Trail, Hawaii 7) Alagnak Wild River, Alaska -

Fort Barry History Tour: an Army Post Standing Guard Over the Marin Headlands National Park Service 2 1 the U.S

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Barry History Tour Fort Barry - Marin Headlands An Army Post Standing Guard Over the Marin Headlands Golden Gate National Parks Fort Barry soldiers with dairy cows. In the early years, the military and the dairy commu- nity lived peacefully side-by-side. However, cows did not always respect military boundaries and occasionally Fort Barry soldiers had to round up wayward dairy cows. (Photo circa 1920) EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICATM Printed on recycled paper with soy-based inks (rev. 1/2011) 0.5 1.2 0.3 1.8 0.3 1.8 1.3 1.5 0.8 0.9 0.3 1.3 1.7 0.7 1.5 0.6 1.2 1.3 1.3 0.4 0.5 0.4 0.7 0.9 1.0 0.5 0.3 0.7 0.4 1.4 0.9 1.1 0.7 0.5 1.3 0.3 0.2 0.7 1.3 0.3 1.0 0.5 1.91.9 0.9 0.7 1.1 1.9 0.6 0.3 0.2 Rodeo 0.2 Marin Headlands 0.9 Visitor Center FORT BARRY The Route Bunker This tour leads you through different parts of historic Fort Barry, covering 5 hilly miles through the Marin Headlands. Stop #1 and Stop # 2 are a comfortable, Road 1-mile walk where you can spend a pleasant hour wandering through the historic 6 buildings. Stops # 3 to # 7 are farther apart and cover approximately 4 miles so Headlands Stables they are better accessed by car. -

Mountain Biking in Marin County Fact Book

MOUNTAIN BIKING IN MARIN COUNTY FACT BOOK THE STATE OF MOUNTAIN BIKING IN MARIN COUNTY For over 100 years, hikers and equestrians have wandered amidst the natural bounty of Marin on narrow trails that began their lives under a varied prove- nance: animal paths, historic Native American footpaths, reclaimed logging roads as well as purpose-built trails. 40 years ago, mountain biking was born right here in Marin on the flanks of Mt. Tam and Pine Mountain. For a brief moment in time, mountain bikers peaceably shared all the trails of Marin with other users. Yet through years of exclusionary legislation, mountain biking in Marin is now largely relegated to fire roads with access to narrow trails disproportionately low compared to other user groups locally as well as compared to mountain bike access in other parts of the Bay THE BIRTHPLACE OF Area, California, the United States and worldwide. MOUNTAIN BIKING This compendium draws on user surveys, peer-reviewed research, comparison studies and public lands policy in Marin County to help provide accurate, current knowledge with the goal of proving two main points: • Mountain biking is a safe, healthy, low-impact activity enjoyed by a significant number and wide cross section of Marin County’s citizens • There is no substantiated, reasonable cause—including safety or enviromental concerns—to prohibit mountain bike access to more narrow trails on public lands in Marin ACCESS4BIKES’ To motivate and empower Marin mountain bikers to act in their own self-interest, to get fair and reasonable access to our public trails and MISSION STATEMENT to preserve the experience of trail riding for future generations. -

A Location Guide for Rock Hounds in the United States

A Location Guide for Rock Hounds in the United States Collected By: Robert C. Beste, PG 1996 Second Edition A Location Guide for Rock Hounds in the United States Published by Hobbit Press 2435 Union Road St. Louis, Missouri 63125 December, 1996 ii A Location Guide for Rock Hounds in the United States Table of Contents Page Preface..................................................................................................................v Mineral Locations by State Alabama ...............................................................................................................1 Alaska.................................................................................................................11 Arizona ...............................................................................................................19 Arkansas ............................................................................................................39 California ...........................................................................................................47 Colorado .............................................................................................................80 Connecticut ......................................................................................................116 Delaware ..........................................................................................................121 Florida ..............................................................................................................122 -

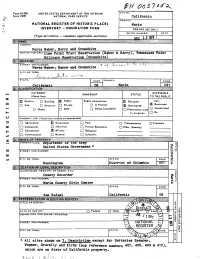

Forts Baker, Barry and Cronkhite Were Continually Modified to Keep Abreast of the Increased Range and Fire Power of Naval Ships

Form ,10-300> UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE California IS COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) 1973 COMMON: Forts Baker, Barry and Cronfchite AND/OR H.sTORic:L_me Point Tract Reservation (Baker & Barry), Tennessee Point ________Military Reservation (Cronkhite)__________________________ STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: COUNTY; California 06 Mar in 041 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District Q Building B Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Yes: (X| Restricted Site Q Structure L~D Private I| In Process Unoccupied Q] Unrestricted D Object Both [~~] Being Considered Preservation work in progress D No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) [ I Agricultural Jrtl Government D Transportation d Comments [ | Commercial [~] Industrial Q Private Residence Other (Specify) [ | Educational [Xj Military Q Religious |~l Entertainment II Museum D Scientific District of Columbia COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC County Recorder Maria County Civic Center San Rafael California FederolQ State DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: ———_____—_—_——.—————————————————————————————•—————————————^*^-L_JL-^ * All sites shown on 7* Description except for Batteries Spencer, Wagner, Gravelly and Kirby (map reference numbers 407, 408, 409 & 410), which are on State of California property. fChecft One) Q Excellent SQ Good D Fair |~) Deteriorated a RU ins [~1 Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) fi Altered D Unaltered D Moved QQ Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The 2,279 acre area of uplands and tidelands comprising Ports Baker, Barry and Cronkhite, extending vest along the north side of the Golden Gate from San Francisco Bay on the east to the Pacific Ocean on the vest has vithin its district many excellent examples of early coastal defense structures.