An Evaluation of the Anti-Trafficking Monitoring Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA Publisher/RRO Title Title code Ad Sales Newquay Voice NV Ad Sales St Austell Voice SAV Ad Sales www.newquayvoice.co.uk WEBNV Ad Sales www.staustellvoice.co.uk WEBSAV Advanced Media Solutions WWW.OILPRICE.COM WEBADMSOILP AJ Bell Media Limited www.sharesmagazine.co.uk WEBAJBSHAR Alliance News Alliance News Corporate ALLNANC Alpha Newspapers Antrim Guardian AG Alpha Newspapers Ballycastle Chronicle BCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymoney Chronicle BLCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymena Guardian BLGU Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Chronicle CCH Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Northern Constitution CNC Alpha Newspapers Countydown Outlook CO Alpha Newspapers Limavady Chronicle LIC Alpha Newspapers Limavady Northern Constitution LNC Alpha Newspapers Magherafelt Northern Constitution MNC Alpha Newspapers Newry Democrat ND Alpha Newspapers Strabane Weekly News SWN Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Constitution TYC Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Courier TYCO Alpha Newspapers Ulster Gazette ULG Alpha Newspapers www.antrimguardian.co.uk WEBAG Alpha Newspapers ballycastle.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBCH Alpha Newspapers ballymoney.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBLCH Alpha Newspapers www.ballymenaguardian.co.uk WEBBLGU Alpha Newspapers coleraine.thechronicle.uk.com WEBCCHR Alpha Newspapers coleraine.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBCNC Alpha Newspapers limavady.thechronicle.uk.com WEBLIC Alpha Newspapers limavady.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBLNC Alpha Newspapers www.newrydemocrat.com WEBND Alpha Newspapers www.outlooknews.co.uk WEBON Alpha Newspapers www.strabaneweekly.co.uk -

Congressional Record—House H2019

May 15, 2020 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H2019 The SPEAKER pro tempore. The Burchett Hollingsworth Rice (SC) b 1246 question is on the resolution. Burgess Hudson Riggleman Byrne Huizenga Roby AFTER RECESS The question was taken; and the Calvert Hurd (TX) Rodgers (WA) Speaker pro tempore announced that Carter (GA) Jayapal Roe, David P. The recess having expired, the House the ayes appeared to have it. Chabot Johnson (LA) Rogers (AL) was called to order by the Speaker pro Cheney Johnson (OH) Mr. WOODALL. Madam Speaker, on Rogers (KY) tempore (Mr. CUELLAR) at 12 o’clock Cline Johnson (SD) Rose, John W. and 46 minutes p.m. that I demand the yeas and nays. Cloud Jordan Rouzer The yeas and nays were ordered. Cole Joyce (OH) Roy f Collins (GA) Joyce (PA) Rutherford The vote was taken by electronic de- Comer Katko AUTHORIZING REMOTE VOTING BY Scalise vice, and there were—yeas 207, nays Conaway Keller Schweikert PROXY AND PROVIDING FOR OF- Cook Kelly (MS) 199, not voting 24, as follows: Scott, Austin Crawford Kelly (PA) FICIAL REMOTE COMMITTEE [Roll No. 106] Crenshaw Khanna Sensenbrenner PROCEEDINGS DURING A PUBLIC YEAS—207 Curtis King (IA) Simpson HEALTH EMERGENCY DUE TO A Davidson (OH) King (NY) Smith (MO) Adams Gabbard Norcross NOVEL CORONAVIRUS Davis, Rodney Kinzinger Smith (NE) Aguilar Gallego O’Halleran Diaz-Balart Kustoff (TN) Smith (NJ) Allred Garamendi Mr. MCGOVERN. Mr. Speaker, pursu- Pallone Duncan LaHood Smucker Barraga´ n Garcia (TX) ant to House Resolution 967, I call up Panetta Dunn LaMalfa Spanberger Bass Golden Pappas Emmer Lamb Spano the resolution (H. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Trinity Mirror…………….………………………………………………...………………………………

Annual Statement to the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO)1 For the period 1 January to 31 December 2017 1Pursuant to Regulation 43 and Annex A of the IPSO Regulations (The Regulations: https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/1240/regulations.pdf) and Clause 3.3.7 of the Scheme Membership Agreement (SMA: https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/1292/ipso-scheme-membership-agreem ent-2016-for-website.pdf) Contents 1. Foreword… ……………………………………………………………………...…………………………... 2 2. Overview… …………………………………………………..…………………...………………………….. 2 3. Responsible Person ……………………………………………………...……………………………... 2 4. Trinity Mirror…………….………………………………………………...……………………………….. 3 4.1 Editorial Standards……………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 4.2 Complaints Handling Process …………………………………....……………………………….. 6 4.3 Training Process…………………………………………....……………...…………………………….. 9 4.4 Trinity Mirror’s Record On Compliance……………………...………………………….…….. 10 5. Schedule ………………………………………………………………………...…...………………………. 16 1 1. Foreword The reporting period covers 1 January to 31 December 2017 (“the Relevant Period”). 2. Overview Trinity Mirror PLC is one of the largest multimedia publishers in the UK. It was formed in 1999 by the merger of Trinity PLC and Mirror Group PLC. In November 2015, Trinity Mirror acquired Local World Ltd, thus becoming the largest regional newspaper publisher in the country. Local World was incorporated on 7 January 2013 following the merger between Northcliffe Media and Iliffe News and Media. From 1 January 2016, Local World was brought in to Trinity Mirror’s centralised system of handling complaints. Furthermore, Editorial and Training Policies are now shared. Many of the processes, policies and protocols did not change in the Relevant Period, therefore much of this report is a repeat of those matters set out in the 2014, 2015 and 2016 reports. 2.1 Publications & Editorial Content During the Relevant Period, Trinity Mirr or published 5 National Newspapers, 207 Regional Newspapers (with associated magazines, apps and supplements as applicable) and 75 Websites. -

FLH Journal 2018 (Pdf) Download

Journal of FRODSHAM AND DISTRICT HISTORY SOCIETY Issue No. 48 November 2018 CONTENTS Pages CHAIRMAN’S INTRODUCTION – Brian Dykes 2 FOUNDING OF FRODSHAM & DISTRICT LOCAL HISTORY GROUP 3 – Arthur R Smith THE PICKERINGS OF FRODSHAM BRIDGE 4-10 – Sue Lorimer & Heather Powling THE GABLES, 52 MAIN STREET, FRODSHAM 11 JAMES HULLEY OF FRODSHAM – Sue Lorimer 12-13 NORLEY HALL & THE WOODHOUSE FAMILY – Kath Gee 14-21 WHITLEY WINDOW, ST JOHN’S CHURCH, ALVANLEY – Sue Lorimer 22 JOHN MILLER 1912-2018 23-24 FINAL ARCHIVE REPORT 14TH MAY– Kath Hewitt 25-27 OUT & ABOUT IN THE COMMUNITY – Editors 28-30 EXTRACT FROM CHESTER CHRONICLE 16TH NOVEMBER 1918 31 PROGRAMME OF MEETINGS 2019 32 Front cover picture: To mark the centenary of votes for women, the theme of Heritage Open Days 2018 was ‘Extraordinary Women’. In Frodsham we were able to celebrate the life of Harriet Shaw Weaver, granddaughter of Edward Abbot Wright of Castle Park. Harriet was born at East Bank (now Fraser House), Bridge Lane on 1st September 1876. The family moved to Hampstead in 1892 when Harriet’s mother, Mary Berry (Wright) Weaver, inherited a considerable fortune on the death of her father. Harriet became a staunch campaigner for women’s rights as well as an important figure in avant-garde literary circles. She died on 14th October 1961. From FDN1856 cheshireimagebank.org.uk 1 CHAIRMAN’S INTRODUCTION Officers: Mr Brian Dykes, Chairman; Dr Kath Gee, Hon.Secretary; Mr David Fletcher, Hon.Treasurer. Committee: Mrs Margaret Dodd, Membership Secretary; Mr Frank Whitfield, Programme Secretary; Mr Andrew Faraday; Mr Brian Keeble; Mrs Pam Keeble; Mrs Heather Powling; Mrs Beryl Wainwright; Mrs Betty Wakefield; Mr Tony Wakefield. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

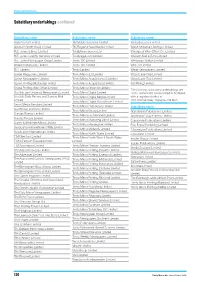

Subsidiary Undertakings Continued

Financial Statements Subsidiary undertakings continued Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Planetrecruit Limited TM Mobile Solutions Limited Websalvo.com Limited Quids-In (North West) Limited TM Regional New Media Limited Welsh Universal Holdings Limited R.E. Jones & Bros. Limited Totallyfinancial.com Ltd Welshpool Web-Offset Co. Limited R.E. Jones Graphic Services Limited Totallylegal.com Limited Western Mail & Echo Limited R.E. Jones Newspaper Group Limited Trinity 100 Limited Whitbread Walker Limited Reliant Distributors Limited Trinity 102 Limited Wire TV Limited RH1 Limited Trinity Limited Wirral Newspapers Limited Scene Magazines Limited Trinity Mirror (L I) Limited Wood Lane One Limited Scene Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions (2) Limited Wood Lane Two Limited Scene Printing (Midlands) Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions Limited Workthing Limited Scene Printing Web Offset Limited Trinity Mirror Cheshire Limited The following subsidiary undertakings are Scottish and Universal Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Digital Limited 100% owned and incorporated in Scotland, Scottish Daily Record and Sunday Mail Trinity Mirror Digital Media Limited with a registered office at Limited One Central Quay, Glasgow, G3 8DA. Trinity Mirror Digital Recruitment Limited Smart Media Services Limited Trinity Mirror Distributors Limited Subsidiary name Southnews Trustees Limited Trinity Mirror Group Limited Aberdonian Publications Limited Sunday Brands Limited Trinity Mirror Huddersfield Limited Anderston Quay Printers Limited Sunday -

Election of the Deputy Speakers Candidates

Election of the Deputy Speakers Candidates 8 January 2020 1 Election of the Deputy Speakers 2 Election of the Deputy Speakers Contents Sir David Amess .......................................... 4 Mr Peter Bone .............................................. 5 Mr Nigel Evans ............................................ 6 Mr Robert Goodwill ................................... 7 Dame Eleanor Laing .................................... 8 Dame Rosie Winterton ............................... 9 Introduction This booklet lists all the candidates for the election of the three Deputy Speakers. The election will take place on Wednesday 8 January 2020 between 10am and 1.30pm in Committee Room 8. The election is governed by Standing Order No. 2A. The candidates are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry gives the candidate’s name and the side of the House they come from. All candidates are required to sign a statement indicating willingness to stand for election. Each candidate’s entry in the booklet prints any further personal statement that has been submitted by that candidate. Constraints will be applied to the count so that of those elected: • two candidates shall come from the opposite side of the House to that from which the Speaker was drawn. So the first candidate from the present Government side will be Chairman of Ways and Means and the second, Second Deputy Chairman of Ways and Means; • one candidate shall come from the same side of the House as that from which the Speaker was drawn and shall be First Deputy Chairman of Ways and Means; and • at least one man and at least one woman shall be elected across the four posts of Speaker and Deputy Speakers. Dame Rosie Winterton is the sole candidate from the same side of the House as that from which the Speaker was drawn, and, having been duly nominated, will be elected First Deputy Chairman of Ways and Means. -

Mr Peter Bone

Wednesday 17 June 2020 Order Paper No.68: Part 1 SUMMARY AGENDA: CHAMBER 11.30am Prayers Deferred divisions will take place in the Members’ Library between 11.30am and 3.30pm Afterwards Oral Questions: Women and Equalities † 12 noon Oral Questions: Prime Minister † Afterwards Urgent Questions, including on: Coronavirus (Secretary of State for Health and Social Care) † Ministerial Statements, including on: Update on the UK’s position on accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) (Secretary of State for International Trade) † 2 Wednesday 17 June 2020 OP No.68: Part 1 Up to 20 Ten Minute Rule Motion: Sexual minutes Offences (Sports Coaches) (Tracey Crouch) Until Divorce, Dissolution and Separation 7.00pm Bill [Lords]: Committee and Remaining Stages No debate Presentation of Public Petitions Until Adjournment Debate: Provision of 7.30pm or asylum seeker services in Glasgow for half an during the covid-19 pandemic (Chris hour Stephens) † Virtual participation in proceedings Wednesday 17 June 2020 OP No.68: Part 1 3 CONTENTS CONTENTS PART 1: BUSINESS TODAY 5 Chamber 9 Deferred Divisions 10 Written Statements 11 Committees Meeting Today 19 Committee reports published today 20 Announcements 22 Further Information PART 2: FUTURE BUSINESS 26 A. Calendar of Business 66 B. Remaining Orders and Notices Updates Notes: Item marked [R] indicates that a member has declared a relevant interest. Wednesday 17 June 2020 OP No.68: Part 1 5 BUSINESS TOday: CHAMBER BUSINESS TODAY: CHAMBER Virtual participation in proceedings will commence after Prayers. 11.30am Prayers Followed by QUESTIONS 1. Women and Equalities 2. Prime Minister The call list for Members participating is available on the House of Commons business papers pages. -

Appendix: “Ideology, Grandstanding, and Strategic Party Disloyalty in the British Parliament”

Appendix: \Ideology, Grandstanding, and Strategic Party Disloyalty in the British Parliament" August 8, 2017 Appendix Table of Contents • Appendix A: Wordscores Estimation of Ideology • Appendix B: MP Membership in Ideological Groups • Appendix C: Rebellion on Different Types of Divisions • Appendix D: Models of Rebellion on Government Sponsored Bills Only • Appendix E: Differences in Labour Party Rebellion Following Leadership Change • Appendix F: List of Party Switchers • Appendix G: Discussion of Empirical Model Appendix A: Wordscores Estimation of Ideology This Appendix describes our method for ideologically scaling British MPs using their speeches on the welfare state, which were originally produced for a separate study on welfare reform (O'Grady, 2017). We cover (i) data collection, (ii) estimation, (iii) raw results, and (iv) validity checks. The resulting scales turn out to be highly valid, and provide an excellent guide to MPs' ideologies using data that is completely separate to the voting data that forms the bulk of the evidence in our paper. A1: Collection of Speech Data Speeches come from an original collection of every speech made about issues related to welfare in the House of Commons from 1987-2007, covering the period over which the Labour party moved 1 to the center under Tony Blair, adopted and enacted policies of welfare reform, and won office at the expense of the Conservatives. Restricting the speeches to a single issue area is useful for estimating ideologies because with multiple topics there is a danger of conflating genuine extremism (a tendency to speak in extreme ways) with a tendency or requirement to talk a lot about topics that are relatively extreme to begin with (Lauderdale and Herzog, 2016). -

OWA Newsletter 2014 PDF File

OLD WESTCLIFFIAN ASSOCIATION (formed 1926) NEWSLETTER 2014 1. OFFICERS & COMMITTEE 2013 - 2014 PRESIDENT - D.A. Norman, MBE, MA CHAIRMAN - M.A. Skelly, MA (Oxon), M.Univ (Open) VICE-PRESIDENTS: HON. SECRETARY - T.W. Birdseye, JP R. Arnold HON. TREASURER - C.R.N. Taylor, FCA T.W. Birdseye, JP HON. ASST. SEC. - R. Arnold H.P. Briggs COMMITTEE MEMBERS: H.W. Browne C.B.E. A.J. Burroughs A.J. Burroughs R.T. Darvell, BA (Hons) Dr. P.L.P. Clarke J. Harrison R.T. Darvell, BA (Hons) A.A. Hurst, BA (Hons) D.A. Day Father J. McCollough J. Harrison School Head Boy, A.A. Hurst, BA (Hons) or his Deputy N.C. Kelleway M. Wren HON. AUDITOR - A.R. Millman, FCA NEWSLETTER EDITOR - A.J. Clarke email: [email protected] Hon. Sec. - Terry Birdseye, JP 810 London Road, Leigh-on-Sea, SS9 3NH Telephone - 01702 714241, Mobile - 07752 192164 email: [email protected] 2. AGM 21ST JULY 8 PM AT THE SCHOOL 3. ANNUAL REUNION DINNER - SATURDAY 12TH SEPTEMBER 2014 6:15 PM FOR 7 PM AT THE SCHOOL. DETAILS ON PAGE 3. Page 1 of 40 CONTENTS 1. Officers & Committee 2013 - 2014. 2. Annual General Meeting, 21st July, 8 pm at the School. 3. O.W.A Annual Reunion Dinner, Saturday 12th September 2014 - 6:15 pm for 7 pm at the School, Kenilworth Gardens, Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex, SS0 0BP. If you would like to look round the School, please be there by 5:30 pm. Details and reply slips on page 3. 4. (i) Honorary Secretary - Careers Guidance Support Form (ii) Honorary Secretary - Newsletter merger with Westcliff Diary (iii) Honorary Secretary’s Report (iii) New Members 5.