The Politics of Revolution; a Film Course Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kino Im Filmmuseum Oktober 2013

Kino im Filmmuseum Oktober 2013 Carte Blanche: Helge Schneider Brasilien Lecture & Film: Andy Warhol Catherine Deneuve zum 70. Fassbinder – Jetzt. Film und Videokunst 2 INFORMATION & TICKETRESERVIERUNG ≥ Tel. 069 - 961 220 220 HELGE SCHNEIDER Impressum 00 Schneider – WendeKreiS DER EIDECHSE ≥ Seite 6 Herausgeber: Deutsches Filminstitut – DIF e.V. Schaumainkai 41 60596 Frankfurt am Main Vorstand: Claudia Dillmann, Dr. Nikolaus Hensel Direktorin: Claudia Dillmann (V.i.S.d.P.) Presse und Redaktion: Frauke Haß (Ltg.), Caroline Goldstein, Dennis Bellof Texte: Natascha Gikas, Caroline Goldstein, Winfried Günther, Frauke Haß, Urs Spörri Gestaltung: Optik — Jens Müller, Sören Lennartz www.optik-studios.de Druck: Fißler & Schröder – Die Produktionsagentur 63150 Heusenstamm Anzeigen (Preise auf Anfrage): Presse- und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Tel.: 069 - 961 220 222 E-Mail: [email protected] Abbildungsverzeichnis: Alle Abbildungen stammen aus dem Bildarchiv des Deutschen Filminstituts – DIF e.V., sofern nicht anders verzeichnet. Titelmotiv: Aus dem Film O SOM AO REDOR (BR 2012) INHALT 3 Filmprogramm Carte Blanche: Helge Schneider 5 Brasilien – ein Land voller Stimmen 12 Klassiker & Raritäten: Catherine Deneuve 22 Lecture & Film: Andy Warhol 24 Late Night Kultkino 28 Kinderkino 30 Specials Lettischer Animationsfilm 32 Was tut sich – im deutschen Film? 34 Kino & Couch 36 Archäologie: Fiktion und Wirklichkeit 37 Fassbinder – JETZT 38 Service Programmübersicht 40 Eintrittspreise/Anfahrt 44 Vorschau 46 FASSbinder – JeTZT ≥ Seite 38 Quelle: Sammlung Peter Gauhe / DIF; Foto: Peter Gauhe 4 AKTUELLES Auszeichnung für das Kino des Deutschen Filmmuseums: Zum 14. Mal hat der Deutsche Kinematheksverbund im September seinen Kinopreis vergeben. In der Kategorie „Vermittlung deutscher und internationaler Filmgeschichte“ erhielt unser Kino den ersten Preis! Wir freuen uns sehr und setzen im Oktober unser Programm gewohnt hoch- wertig und frisch motiviert fort. -

Eric Rohmer's Film Theory (1948-1953)

MARCO GROSOLI FILM THEORY FILM THEORY ERIC ROHMER’S FILM THEORY (1948-1953) IN MEDIA HISTORY IN MEDIA HISTORY FROM ‘ÉCOLE SCHERER’ TO ‘POLITIQUE DES AUTEURS’ MARCO GROSOLI ERIC ROHMER’S FILM THEORY ROHMER’S ERIC In the 1950s, a group of critics writing MARCO GROSOLI is currently Assistant for Cahiers du Cinéma launched one of Professor in Film Studies at Habib Univer- the most successful and influential sity (Karachi, Pakistan). He has authored trends in the history of film criticism: (along with several book chapters and auteur theory. Though these days it is journal articles) the first Italian-language usually viewed as limited and a bit old- monograph on Béla Tarr (Armonie contro fashioned, a closer inspection of the il giorno, Bébert 2014). hundreds of little-read articles by these critics reveals that the movement rest- ed upon a much more layered and in- triguing aesthetics of cinema. This book is a first step toward a serious reassess- ment of the mostly unspoken theoreti- cal and aesthetic premises underlying auteur theory, built around a recon- (1948-1953) struction of Eric Rohmer’s early but de- cisive leadership of the group, whereby he laid down the foundations for the eventual emergence of their full-fledged auteurism. ISBN 978-94-629-8580-3 AUP.nl 9 789462 985803 AUP_FtMh_GROSOLI_(rohmer'sfilmtheory)_rug16.2mm_v02.indd 1 07-03-18 13:38 Eric Rohmer’s Film Theory (1948-1953) Film Theory in Media History Film Theory in Media History explores the epistemological and theoretical foundations of the study of film through texts by classical authors as well as anthologies and monographs on key issues and developments in film theory. -

Film, Photojournalism, and the Public Sphere in Brazil and Argentina, 1955-1980

ABSTRACT Title of Document: MODERNIZATION AND VISUAL ECONOMY: FILM, PHOTOJOURNALISM, AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA, 1955-1980 Paula Halperin, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Directed By: Professor Barbara Weinstein Department of History University of Maryland, College Park My dissertation explores the relationship among visual culture, nationalism, and modernization in Argentina and Brazil in a period of extreme political instability, marked by an alternation of weak civilian governments and dictatorships. I argue that motion pictures and photojournalism were constitutive elements of a modern public sphere that did not conform to the classic formulation advanced by Jürgen Habermas. Rather than treating the public sphere as progressively degraded by the mass media and cultural industries, I trace how, in postwar Argentina and Brazil, the increased production and circulation of mass media images contributed to active public debate and civic participation. With the progressive internationalization of entertainment markets that began in the 1950s in the modern cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires there was a dramatic growth in the number of film spectators and production, movie theaters and critics, popular magazines and academic journals that focused on film. Through close analysis of images distributed widely in international media circuits I reconstruct and analyze Brazilian and Argentine postwar visual economies from a transnational perspective to understand the constitution of the public sphere and how modernization, Latin American identity, nationhood, and socio-cultural change and conflict were represented and debated in those media. Cinema and the visual after World War II became a worldwide locus of production and circulation of discourses about history, national identity, and social mores, and a space of contention and discussion of modernization. -

MEDIA-MAKERS FORUM October 8 • 12-4 PM • FREE Join Our Four-Person Panel As They Discuss the Not-For-Profit Filmmaking Going on in the Area

MEDIA-MAKERS FORUM October 8 • 12-4 PM • FREE Join our four-person panel as they discuss the not-for-profit filmmaking going on in the area. It’s your chance to help make movies! See you at The Neville Public Museum! Wednesday, September 21 • THE RETURN (Russia, 2003) Directed by Andrei Zvyagintsev Winner of the Golden Lion at the 2003 Venice Film Festival, “The Return” is a magnificent re-working of the prodigal son parable, this time with the father returning to his two sons after a 12 year absence. Though at first ecstatic to be reunited with the father they’ve only known from a photograph, the boys strain under the weight of their dad’s awkward and sometimes brutal efforts to make up for the missing years. In Russian with English subtitles. Presenter to be announced Wednesday, October 12 • BRIGHT FUTURE (Japan, 2003) Directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa Called by the New York Times a Japanese David Lynch, Kurosawa’s film is about two young friends who work at a hand-towel factory and raise deadly jellyfish. A casual visit by their boss unleashes a serious of events which change the two friends lives forever. One of the pleasures of this slow, suspenseful film is how casually Kurosawa tosses in ideas about contemporary life, the state of the family, the place of technology, all while steadily shredding your nerves. In Japanese with English subtitles. Presented by Ben Birkinbine, Green Bay Film Society Wednesday, October 19 • OSCAR-NOMINATED AND OSCAR-WINNING SHORT FILMS Once again we present a series of the best of live-action and animated short films from around the world. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

1 Film 5900/7900

FILM 5900/7900 - Film Theory Fall 2017 Prof. Rielle Navitski [email protected] Class: T/Th 2:00 – 3:15 pm in 53 Fine Arts Screening: Th 3:30 – 6:15 pm in 53 Fine Arts Office hours: T/W 10:00 am – 12:00 pm or by appointment in 260 Fine Arts Course Description: This course explores a range of critics’, scholars’ and filmmakers’ positions on the “big questions” that arise in relation to films considered as artistic objects and the production and consumption of films considered as meaningful individual and social experiences. Beginning with key debates in film theory and working mostly chronologically, we will consider critic André Bazin’s famous question “what is cinema?” Is it more useful to try to define film’s unique characteristics or to chart its overlap – particularly in a digital age – with other audio/visual media and other visual and performing arts? Should more weight be given to film’s capacity to record and play back a recognizable impression of the visible and audible world, or to its formal or aesthetic qualities – arrangements of light, sound, and time – and the way it communicates meanings through stylistic elements like editing, camera movement, and mise-en-scène. How do elements of film style and the institutions surrounding cinema – from the studio to the movie theater to fan culture – impact spectators’ experiences? How do gender, sexuality, race, and nation shape film aesthetics and viewing experiences? Without seeking to definitively resolve these debates, we will consider how they can meaningfully inform our role as consumers and producers of media. -

Entretien Avec Fernando Solanas : La Déchirure

Document generated on 09/29/2021 5:14 p.m. 24 images Entretien avec Fernando Solanas La déchirure Janine Euvrard Cinéma et exil Number 106, Spring 2001 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/23987ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Euvrard, J. (2001). Entretien avec Fernando Solanas : la déchirure. 24 images, (106), 33–38. Tous droits réservés © 24 images, 2001 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ CINÉMA ET EXIL Entretien avec Fernando Solanas LA DÉCHIRURE PROPOS RECUEILLIS PAR JANINE EUVRARD 24 IMAGES: Au mot exil dans le Petit Larousse, on lit «expulsion». Ce n'est pas toujours le cas; parfois la personne prend les devants et part avant d'être expulsée. Pouvez-vous nous raconter votre départ d'Argentine? Il est des cinéastes pour qui la vie, la création, le rapport FERNANDO SOLANAS: Votre question est intéressante. Il y a au pays et le combat politique sont viscéralement indisso souvent confusion, amalgame, lorsqu'on parle de gens qui quittent leur pays sans y être véritablement obligés, sans y être vraiment en ciables. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Cinema in Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’

Cinema In Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’ Manuel Ramos Martínez Ph.D. Visual Cultures Goldsmiths College, University of London September 2013 1 I declare that all of the work presented in this thesis is my own. Manuel Ramos Martínez 2 Abstract Political names define the symbolic organisation of what is common and are therefore a potential site of contestation. It is with this field of possibility, and the role the moving image can play within it, that this dissertation is concerned. This thesis verifies that there is a transformative relation between the political name and the cinema. The cinema is an art with the capacity to intervene in the way we see and hear a name. On the other hand, a name operates politically from the moment it agitates a practice, in this case a certain cinema, into organising a better world. This research focuses on the audiovisual dynamism of the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’ and ‘people’ in contemporary cinemas. It is not the purpose of the argument to nostalgically maintain these old revolutionary names, rather to explore their efficacy as names-in-dispute, as names with which a present becomes something disputable. This thesis explores this dispute in the company of theorists and audiovisual artists committed to both emancipatory politics and experimentation. The philosophies of Jacques Rancière and Alain Badiou are of significance for this thesis since they break away from the semiotic model and its symptomatic readings in order to understand the name as a political gesture. Inspired by their affirmative politics, the analysis investigates cinematic practices troubled and stimulated by the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’, ‘people’: the work of Peter Watkins, Wang Bing, Harun Farocki, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

Une Année Studieuse

Extrait de la publication DU MÊME AUTEUR Aux Éditions Gallimard DES FILLES BIEN ÉLEVÉES MON BEAU NAVIRE (Folio no 2292) MARIMÉ (Folio no 2514) CANINES (Folio no 2761) HYMNES À L’AMOUR (Folio no 3036) UNE POIGNÉE DE GENS. Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie française 1998 (Folio no 3358) AUX QUATRE COINS DU MONDE (Folio no 3770) SEPT GARÇONS (Folio no 3981) JE M’APPELLE ÉLISABETH (Folio no 4270) L’ÎLE. Nouvelle extraite du recueil DES FILLES BIEN ÉLEVÉES (Folio 2 € no 4674) JEUNE FILLE (Folio no 4722) MON ENFANT DE BERLIN (Folio no 5197) Extrait de la publication une année studieuse Extrait de la publication Extrait de la publication ANNE WIAZEMSKY UNE ANNÉE STUDIEUSE roman GALLIMARD © Éditions Gallimard, 2012. Extrait de la publication À Florence Malraux Extrait de la publication Un jour de juin 1966, j’écrivis une courte lettre à Jean-Luc Godard adressée aux Cahiers du Cinéma, 5 rue Clément-Marot, Paris 8e. Je lui disais avoir beaucoup aimé son dernier i lm, Masculin Féminin. Je lui disais encore que j’aimais l’homme qui était derrière, que je l’aimais, lui. J’avais agi sans réaliser la portée de certains mots, après une conversation avec Ghislain Cloquet, rencontré lors du tournage d’Au hasard Balthazar de Robert Bresson. Nous étions demeurés amis, et Ghislain m’avait invitée la veille à déjeuner. C’était un dimanche, nous avions du temps devant nous et nous étions allés nous promener en Normandie. À un moment, je lui parlai de Jean-Luc Godard, de mes regrets au souvenir de trois rencontres « ratées ». -

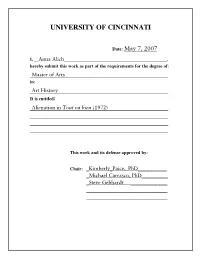

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film.