The View from Tehran: Iran's Militia Doctrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Arab Spring Or Arab Winter (Or Both)? Implications for U.S. Policy

www.pomed.org ♦ 1820 Jefferson Place NW, Suite 400 ♦ Washington, DC 20036 “Arab Spring or Arab Winter (or Both)? Implications for U.S. Policy” The Middle East Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars 1300 Pennsylvania Ave., NW Tuesday July 19th, 9:30 a.m.-11:00 a.m. On Tuesday, the Middle East Program hosted an event at the Woodrow Wilson Center entitled “Arab Spring or Arab Winter (or Both)? Implications for U.S. Policy” featuring expert panelists: Marwan Muasher, Vice President for studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Ellen Laipson, President and CEO of the Stimson Center; Rami G.Khouri, Director of the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut; and Aaron David Miller, Public Policy Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center. Ellen Laipson asserted that the movement in the Middle East has surpassed a „season‟ and will prove to be an enduring and prevailing issue in global politics. She stated that overall, the movement was a “net positive for the region” although there is still unsettling uncertainty in the area. She also discussed a global transition that is taking place, where middle powers are rising and the U.S.‟ regional influences are diminishing. Also, she proposed the question of how the U.S. can initiate conversations with countries in the Middle East which haven‟t faced a revolutionary transition yet. Lastly, Laipson discussed how the U.S., as a part of the international community whole, can continue to promote democracy and institution-building in transitional governments. She noted that the security agenda mustn‟t be dismissed, and that security sector reform needs to be a part of the overall effort of the reform process. -

Iraq Has Now Spent Five Years Under Military Occupation, and The

Iraqhasnowspentfiveyearsundermilitary occupation,andthesufferingoftheIraqi peoplecontinues. WithgrowingpressuretowithdrawUSandUK troopsfromIraq,mercenaryforceshavebeengiven anevergreaterroleintheconflict,makinghundreds ofmillionsofpoundsforthecorporationsthat supplythem. Thecompaniesgrowricherwhile wholecommunitiesarecondemnedtothelong- termpovertywhichcomeswithwar. Despitehundredsofcasesofhumanrights abusebymercenaryforcesoverthepastfiveyears, privatearmieshavebeenimmunefromprosecution. WaronWantisleadingthecampaignforUK legislationtobantheuseofmercenaries inwarandtoregulatetheiractivitiesclosely inallotherarenas. February 2008 Stills from two ‘trophy videos’ shot by PMSCs in Iraq. The videos can be found at www.waronwant.org/pmsc War is one of the chief causes of poverty, headlines and brought scrutiny on the entire destroying schools, hospitals, industry and any industry. But this is far from the only example hopes for development. We did not need the of human rights abuse perpetrated by twin catastrophes of the Afghanistan and Iraq mercenary forces in Iraq: invasions to teach us this. But not everyone is made poorer by war. Many companies • In November 2007 an Iraqi taxi driver was thrive off conflict, and indeed have a vested shot and killed by mercenaries working for interest in seeing it continue. DynCorp International, a private military company hired to protect American diplomats. War on Want brought the problem of private armies to the public’s attention with • In October 2007 mercenaries from Australian our acclaimed report Corporate Mercenaries. firm Unity Resources Group killed two Iraqi The concerns we raised in that report have women in an attack that saw 40 shots fired now turned into public outrage, with new at their car. examples of human rights violations by mercenaries in Iraq coming to light every • In the same month mercenaries working for week.We are stepping up the pressure on UK company Erinys International opened fire the UK government to introduce legislation on a taxi near Kirkuk, wounding three civilians. -

Adaptation Strategies of Islamist Movements April 2017 Contents

POMEPS STUDIES 26 islam in a changing middle east Adaptation Strategies of Islamist Movements April 2017 Contents Understanding repression-adaptation nexus in Islamist movements . 4 Khalil al-Anani, Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, Qatar Why Exclusion and Repression of Moderate Islamists Will Be Counterproductive . 8 Jillian Schwedler, Hunter College, CUNY Islamists After the “Arab Spring”: What’s the Right Research Question and Comparison Group, and Why Does It Matter? . 12 Elizabeth R. Nugent, Princeton University The Islamist voter base during the Arab Spring: More ideology than protest? . .. 16 Eva Wegner, University College Dublin When Islamist Parties (and Women) Govern: Strategy, Authenticity and Women’s Representation . 21 Lindsay J. Benstead, Portland State University Exit, Voice, and Loyalty Under the Islamic State . 26 Mara Revkin, Yale University and Ariel I. Ahram, Virginia Tech The Muslim Brotherhood Between Party and Movement . 31 Steven Brooke, The University of Louisville A Government of the Opposition: How Moroccan Islamists’ Dual Role Contributes to their Electoral Success . 34 Quinn Mecham, Brigham Young University The Cost of Inclusion: Ennahda and Tunisia’s Political Transition . 39 Monica Marks, University of Oxford Regime Islam, State Islam, and Political Islam: The Past and Future Contest . 43 Nathan J. Brown, George Washington University Middle East regimes are using ‘moderate’ Islam to stay in power . 47 Annelle Sheline, George Washington University Reckoning with a Fractured Islamist Landscape in Yemen . 49 Stacey Philbrick Yadav, Hobart and William Smith Colleges The Lumpers and the Splitters: Two very different policy approaches on dealing with Islamism . 54 Marc Lynch, George Washington University The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network that aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . -

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’S Revolutionary Guard

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard SAEID GOLKAR AUGUST 2021 KASRA AARABI Contents Executive Summary 4 The Raisi Administration, the IRGC and the Creation of a New Islamic Government 6 The IRGC as the Foundation of Raisi’s Islamic Government The Clergy and the Guard: An Inseparable Bond 16 No Coup in Sight Upholding Clerical Superiority and Preserving Religious Legitimacy The Importance of Understanding the Guard 21 Shortcomings of Existing Approaches to the IRGC A New Model for Understanding the IRGC’s Intra-elite Factionalism 25 The Economic Vertex The Political Vertex The Security-Intelligence Vertex Charting IRGC Commanders’ Positions on the New Model Shades of Islamism: The Ideological Spectrum in the IRGC Conclusion 32 About the Authors 33 Saeid Golkar Kasra Aarabi Endnotes 34 4 The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi Executive Summary “The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps [IRGC] has excelled in every field it has entered both internationally and domestically, including security, defence, service provision and construction,” declared Ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi, then chief justice of Iran, in a speech to IRGC commanders on 17 March 2021.1 Four months on, Raisi, who assumes Iran’s presidency on 5 August after the country’s June 2021 election, has set his eyes on further empowering the IRGC with key ministerial and bureaucratic positions likely to be awarded to guardsmen under his new government. There is a clear reason for this ambition. Expanding the power of the IRGC serves the interests of both Raisi and his 82-year-old mentor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic. -

Iran 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

IRAN 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution defines the country as an Islamic republic and specifies Twelver Ja’afari Shia Islam as the official state religion. It states all laws and regulations must be based on “Islamic criteria” and an official interpretation of sharia. The constitution states citizens shall enjoy human, political, economic, and other rights, “in conformity with Islamic criteria.” The penal code specifies the death sentence for proselytizing and attempts by non-Muslims to convert Muslims, as well as for moharebeh (“enmity against God”) and sabb al-nabi (“insulting the Prophet”). According to the penal code, the application of the death penalty varies depending on the religion of both the perpetrator and the victim. The law prohibits Muslim citizens from changing or renouncing their religious beliefs. The constitution also stipulates five non-Ja’afari Islamic schools shall be “accorded full respect” and official status in matters of religious education and certain personal affairs. The constitution states Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians, excluding converts from Islam, are the only recognized religious minorities permitted to worship and form religious societies “within the limits of the law.” The government continued to execute individuals on charges of “enmity against God,” including two Sunni Ahwazi Arab minority prisoners at Fajr Prison on August 4. Human rights nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) continued to report the disproportionately large number of executions of Sunni prisoners, particularly Kurds, Baluchis, and Arabs. Human rights groups raised concerns regarding the use of torture, beatings in custody, forced confessions, poor prison conditions, and denials of access to legal counsel. -

Yemen in Crisis

A Conflict Overlooked: Yemen in Crisis Jamison Boley Kent Evans Sean Grassie Sara Romeih Conflict Risk Diagnostic 2017 Conflict Background Yemen has a weak, highly decentralized central government that has struggled to rule the northern Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) and the southern People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY).1 Since the unification of these entities in 1990, Yemen has experienced three civil conflicts. As the poorest country in the Arab world, Yemen faces serious food and water shortages for a population dispersed over mountainous terrain.2 The country’s weaknesses have been exploited by Saudi Arabia which shares a porous border with Yemen. Further, the instability of Yemen’s central government has created a power vacuum filled by foreign states and terrorist groups.3 The central government has never had effective control of all Yemeni territory. Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was president of Yemen for 34 years, secured his power through playing factions within the population off one another. The Yemeni conflict is not solely a result of a Sunni-Shia conflict, although sectarianism plays a role.4 The 2011 Arab Spring re-energized the Houthi movement, a Zaydi Shia movement, which led to the overthrow of the Saleh government. Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi took office as interim president in a transition led by a coalition of Arab Gulf states and backed by the United States. Hadi has struggled to deal with a variety of problems, including insurgency, the continuing loyalty of many military officers to former president Saleh, as well as corruption, unemployment and food insecurity.5 Conflict Risk Diagnostic Indicators Key: (+) Stabilizing factor; (-) Destabilizing factor; (±) Mixed factor Severe Risk - Government military expenditures have been generally stable between 2002-2015, at an average of 4.8% of GDP. -

Traders, Pirates, Warriors: the Proto-History of Greek Mercenary Soldiers in the Eastern Mediterranean Author(S): Nino Luraghi Source: Phoenix, Vol

Classical Association of Canada Traders, Pirates, Warriors: The Proto-History of Greek Mercenary Soldiers in the Eastern Mediterranean Author(s): Nino Luraghi Source: Phoenix, Vol. 60, No. 1/2 (Spring - Summer, 2006), pp. 21-47 Published by: Classical Association of Canada Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20304579 Accessed: 06/09/2010 12:51 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cac. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Classical Association of Canada is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Phoenix. http://www.jstor.org TRADERS, PIRATES,WARRIORS: THE PROTOHISTORY OF GREEKMERCENARY SOLDIERS IN THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN Nino Luraghi Fot the colleagues and students of theDepattment of Classics, UnivetsityofTotonto he that mercenary soldiers 1 fact Greek had been serving for a number of powers in the southeastern Mediterranean during most of the archaic age a on hardly strikes reader engaged in general readings archaic Greek history. -

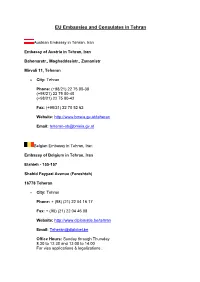

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran Austrian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Austria in Tehran, Iran Bahonarstr., Moghaddasistr., Zamanistr Mirvali 11, Teheran City: Tehran Phone: (+98/21) 22 75 00-38 (+98/21) 22 75 00-40 (+98/21) 22 75 00-42 Fax: (+98/21) 22 70 52 62 Website: http://www.bmeia.gv.at/teheran Email: [email protected] Belgian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Belgium in Tehran, Iran Elahieh - 155-157 Shahid Fayyazi Avenue (Fereshteh) 16778 Teheran City: Tehran Phone: + (98) (21) 22 04 16 17 Fax: + (98) (21) 22 04 46 08 Website: http://www.diplomatie.be/tehran Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Sunday through Thursday 8.30 to 12.30 and 13.00 to 14.00 For visa applications & legalizations : Sunday through Tuesday from 8.30 to 11.30 AM Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran IR Iran, Tehran, 'Vali-e Asr' Ave. 'Tavanir' Str., 'Nezami-ye Ganjavi' Str. No. 16-18 City: Tehran Phone: (009821) 8877-5662 (009821) 8877-5037 Fax: (009821) 8877-9680 Email: [email protected] Croatian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Croatia in Tehran, Iran 1. Behestan 25 Avia Pasdaran Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran City: Tehran Phone: 0098 21 258 9923 0098 21 258 7039 Fax: 0098 21 254 9199 Email: [email protected] Details: Covers the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Details: Ambassador: William Carbó Ricardo Cypriot Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Cyprus in Tehran, Iran 328, Shahid Karimi (ex. -

PROTESTS and REGIME SUPPRESSION in POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY n OCTOBER 2020 n PN85 PROTESTS AND REGIME SUPPRESSION IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar Green Movement members tangle with Basij and police forces, 2009. he nationwide protests that engulfed Iran in late 2019 were ostensibly a response to a 50 percent gasoline price hike enacted by the administration of President Hassan Rouhani.1 But in little time, complaints Textended to a broader critique of the leadership. Moreover, beyond the specific reasons for the protests, they appeared to reveal a deeper reality about Iran, both before and since the 1979 emergence of the Islamic Republic: its character as an inherently “revolutionary country” and a “movement society.”2 Since its formation, the Islamic Republic has seen multiple cycles of protest and revolt, ranging from ethnic movements in the early 1980s to urban riots in the early 1990s, student unrest spanning 1999–2003, the Green Movement response to the 2009 election, and upheaval in December 2017–January 2018. The last of these instances, like the current round, began with a focus on economic dissatisfaction and then spread to broader issues. All these movements were put down by the regime with characteristic brutality. © 2020 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. SAEID GOLKAR In tracking and comparing protest dynamics and market deregulation, currency devaluation, and the regime responses since 1979, this study reveals that cutting of subsidies. These policies, however, spurred unrest has become more significant in scale, as well massive inflation, greater inequality, and a spate of as more secularized and violent. -

Manifestation of Religious Authority on the Internet: Presentation of Twelver Shiite Authority in the Persian Blogosphere By

Manifestation of Religious Authority on the Internet: Presentation of Twelver Shiite Authority in the Persian Blogosphere by Narges Valibeigi A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2012 © Narges Valibeigi 2012 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Narges Valibeigi ii Abstract Cyberspace has diversified and pluralized people’s daily experiences of religion in unprecedented ways. By studying several websites and weblogs that have a religious orientation, different layers of religious authority including “religious hierarchy, structures, ideology, and sources” (Campbell, 2009) can be identified. Also, using Weber’s definition of the three types of authority, “rational-legal, traditional, and charismatic” (1968), the specific type of authority that is being presented on blogosphere can be recognized. The Internet presents a level of liberty for the discussion of sensitive topics in any kind of religious cyberspace, specifically the Islamic one. In this way, the Internet is expanding the number and range of Muslim voices, which may pose problems for traditional forms of religious authority or may suggest new forms of authority in the Islamic world. The interaction between the Internet and religion is often perceived as contradictory, especially when it is religion at its most conservative practice. While the international and national applications of the Internet have increased vastly, local religious communities, especially fundamentalists, perceived this new technology as a threat to their local cultures and practices. -

The Middle East After the Iraq War

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Project AIR FORCE View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. THE IRAQ EFFECT The Middle East After the Iraq War Frederic Wehrey Dalia Dassa Kaye Jessica Watkins Jeffrey Martini Robert A. -

Iran's Nuclear Program: Tehran's Compliance with International

Iran’s Nuclear Program: Tehran’s Compliance with International Obligations Updated August 18, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R40094 SUMMARY R40094 Iran’s Nuclear Program: Tehran’s Compliance August 18, 2021 with International Obligations Paul K. Kerr Several U.N. Security Council resolutions adopted between 2006 and 2010 required Iran to Specialist in cooperate fully with the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA’s) investigation of its Nonproliferation nuclear activities, suspend its uranium enrichment program, suspend its construction of a heavy- water reactor and related projects, and ratify the Additional Protocol to its IAEA safeguards agreement. Iran did not comply with most of the resolutions’ provisions. However, Tehran has implemented various restrictions on, and provided the IAEA with additional information about, the government’s nuclear program pursuant to the July 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which Tehran concluded with China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. On the JCPOA’s Implementation Day, which took place on January 16, 2016, all of the previous resolutions’ requirements were terminated. The nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and U.N. Security Council Res olution 2231, which the Council adopted on July 20, 2015, compose the current legal framework governing Iran’s nuclear program. The United States attempted in 2020 to reimpose sanctions on Iran via a mechanism provided for in Resolution 2231. However, the Security Council did not do so. Iran and the IAEA agreed in August 2007 on a work plan to clarify outstanding questions regarding Tehran’s nuclear program. The IAEA had essentially resolved most of these issues, but for several years the agency still had questions concerning “possible military dimensions to Iran’s nuclear programme.” A December 2, 2015, report to the IAEA Board of Governors from then-agency Director General Yukiya Amano contains the IAEA’s “final assessment on the resolution” of the outstanding issues.