Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 General Catalog

MASTERS SERIES Masters Series Lacquer Finish . Available Colors MMX MRX MHX BRX Masters Series Covered Finish . Available Colors MSX No.100 Wine Red No.400 White Marine Pearl No.102 Natural Maple No.401 Royal Gold No.103 Piano Black No.402 Abalone No.112 Natural Birch No.403 Red Onyx No.122 Black Mist No.404 Amethyst No.128 Vintage Sunburst No.141 Red Mahogany No.148 Emerald Fade No.151 Platinum Mist PEARL DRUMS No.152 Antique Gold No.153 Sunrise Fade m No.154 Midnight Fade o c . No.156 Purple Storm m No.160 Silver Sparkle u r d No.165 Diamond Burst l r No.166 Black Sparkle a e p No.168 Ocean Sparkle . w w w SESSION / EXPORT / FORUM / RHYTHM TRAVELER . Lacquer Finish Available Colors SMX SBX ELX Covered Finish Available Colors EXR EX FX RT www.pearldrum.com No.281 Carbon Mist No.430 Prizm Blue No.290 Vintage Fade No.431 Strata Black No.291 Cranberry Fade No.432 Prizm Purple No.292 Marine Blue Fade No.433 Strata White No.296 Green Burst No.21 Smokey Chrome No.280 Vintage Wine No.31 Jet Black No.283 Solid Black No.33 Pure White No.284 Tobacco Burst No.49 Polished Chrome No.289 Blue Burst No.78 Teal Metallic No.271 Ebony Mist No.91 Red Wine No.273 Blue Mist No.95 Deep Blue No.274 Amber Mist No.98 Charcoal Metallic No.294 Amber Fade No.295 Ruby Fade No.299 Cobalt Fade For more information on these or any Pearl product, visit your local authorized Pearl Dealer. -

The Authenticity of Ambiguity: Dada and Existentialism

THE AUTHENTICITY OF AMBIGUITY: DADA AND EXISTENTIALISM by ELIZABETH FRANCES BENJAMIN A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham August 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ii - ABSTRACT - Dada is often dismissed as an anti-art movement that engaged with a limited and merely destructive theoretical impetus. French Existentialism is often condemned for its perceived quietist implications. However, closer analysis reveals a preoccupation with philosophy in the former and with art in the latter. Neither was nonsensical or meaningless, but both reveal a rich individualist ethics aimed at the amelioration of the individual and society. It is through their combined analysis that we can view and productively utilise their alignment. Offering new critical aesthetic and philosophical approaches to Dada as a quintessential part of the European Avant-Garde, this thesis performs a reassessment of the movement as a form of (proto-)Existentialist philosophy. The thesis represents the first major comparative study of Dada and Existentialism, contributing a new perspective on Dada as a movement, a historical legacy, and a philosophical field of study. -

La Representación De La Visión En El Cine De Los Surrealistas

Máster en Estudios Comparados de Literatura, Arte y Pensamiento Iniciación a la investigación La representación de la visión en el cine de los surrealistas Ainamar Clariana Rodagut Directora de la investigación: Dra. Victoria Cirlot Curso 2011-2012 3 de septiembre de 2012 1 ÍNDICE Introducción...................................................................................................................................3 1. El cine de los surrealistas................................................................................................11 1. 1 Contexto.....................................................................................................................11 1.2 La experiencia de los surrealistas: el cine como sueño........................................13 1.3 El cine surrealista como transgresión....................................................................17 1.4 La imposibilidad de un cine surrealista..................................................................17 1.5 Diversas formas de tratar la relación entre surrealismo y cine..........................18 1.6 La obra de cada autor y los elementos surrealistas..............................................25 1.7 El sueño surrealista: liberar al espectador a través del cine................................26 1.8 La práctica subversiva y el discurso narrativo.......................................................28 1.9 Conclusión.................................................................................................................29 2. Emak Bakia........................................................................................................................31 -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

The Creative Restlessness of Lee Miller's

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 14 | 2017 Early American Surrealisms, 1920-1940 / Parable Art Sands of desire : the Creative Restlessness of Lee Miller’s Egyptian Period Peter Schulman Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/9855 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.9855 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Peter Schulman, “Sands of desire : the Creative Restlessness of Lee Miller’s Egyptian Period”, Miranda [Online], 14 | 2017, Online since 03 April 2017, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/9855 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.9855 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Sands of desire : the Creative Restlessness of Lee Miller’s Egyptian Period 1 Sands of desire : the Creative Restlessness of Lee Miller’s Egyptian Period Peter Schulman 1 “As a spectator, I wanted to explore photography not as a question (a theme) but as a wound,” Roland Barthes writes in Camera Lucida (Barthes 17). Similarly, in the famous first lines of his surrealist book Nadja, André Breton concluded that the question he should ask himself should be “not who I am, but whom I haunt” (Breton 7). Could either of these quotes apply to Lee Miller’s aesthetic as well ? While her photographs during her period of soi-disant “apprenticeship” 1 with Man Ray focused on the female body, and the ones in her studio in New York on elegant portraiture, it is during her period in Egypt when she was married to the wealthy, older Egyptian businessman Aziz Eloui Bey that her photography truly blossomed into her own aesthetic which “married” the humor and the ludic notions of space found in certain Magritte paintings with the curious gaze of the ‘other’ that she would develop as a photo-journalist during the war. -

Man Ray Im Urteil Der Zeitgenössischen Kunstliteratur

Man Ray im Urteil der zeitgenössischen Kunstliteratur unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des multimedialen Angebots Diplomarbeit im Fach Kunstwissenschaft und Kunstinformationswesen Studiengang Wissenschaftliche Bibliotheken der Fachhochschule Stuttgart – Hochschule der Medien Corinna Herrmann Erstprüferin: Prof. Dr. Gudrun Calov Zweitprüfer: Prof. Dr. Gerhard Kuhlemann Bearbeitungszeitraum: 15. Juli 2002 bis 15. Oktober 2002 Stuttgart, Oktober 2002 Kurzfassung 2 Kurzfassung Die vorliegende Diplomarbeit behandelt das Werk Man Rays und die Auswirkungen seiner Arbeiten auf die heutige Zeit. Die einführende Kurzbiografie liefert einen Überblick über sein Leben. Es folgt die Darstellung seines Lebenswerks mit den Auswirkungen auf die moderne Kunst, insbesondere die Fotografie. Anschließend wird das Ausstellungswesen zu Man Ray untersucht. Die folgende Betrachtung der zeitgenössischen Kunstliteratur geht im besonderen auf das multimediale Angebot zu Man Ray ein. Den Abschluss bildet die Darstellung von Man Ray in der Öffentlichkeit anhand des Kunstmarkts und anhand seiner Werke in Museen und Artotheken. Schlagwörter: Man Ray, Fotografie, Kunstliteratur, Kunstmarkt, Neue Medien, Diplomarbeit Abstract This diploma thesis presents the work of Man Ray and discusses its influence on the world of art today. First, an overview of his life is given, followed by a description of his works and the effects on modern art and in particular on photography. Next, Man Ray’s exhibition will be examined. Some of the contemporary art literature is presented, -

16 BRIAN JARVIS Thomas Pynchon Thomas Pynchon Is Perhaps Best

16 BRIAN JARVIS Thomas Pynchon Thomas Pynchon is perhaps best known for knowing a lot and not being known. His novels and the characters within them are typically engaged in the manic collection of information. Pynchon’s fiction is crammed with erudition on a vast range of subjects that includes history, science, technology, religion, the arts, and popular culture. Larry McMurtry recalls a legend that circulated in the sixties that Pynchon “read only the Encyclopaedia Britannica.”1 While Pynchon is renowned for the breadth and depth of his knowledge, he has performed a “calculated withdrawal” from the public sphere.2 He has never been interviewed. He has been photographed on only a handful of occasions (most recently in 1957). Inevitably, this reclusion has enhanced his cult status and prompted wild speculation (including the idea that Pynchon was actually J. D. Salinger). Reliable information about Pynchon practically disappears around the time his first novel was published in 1963. While Pynchon the author is a conspicuous absence in the literary marketplace, his fiction is a commanding presence. His first major work, V. (1963), has a contrapuntal structure in which two storylines gradually converge. The first line, set in New York in the 1950s, follows Benny Profane and a group of his bohemian acquaintances self-designated the “Whole Sick Crew.” The second line jumps between moments of historical crisis, from the Fashoda incident in 1898 to the Second World War and centers on Herbert Stencil’s quest for a mysterious figure known as “V.” Pynchon's second novel, The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), is arguably his most accessible work and has certainly been the most conspicuous on university syllabuses. -

Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative

Overwhelmed and Underworked: Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative Miles Taylor A Thesis in The Department of Film Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada May 2020 © Miles Taylor 2020 Signature Page This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Miles Taylor Entitled: Overwhelmed and Underworked: Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative And submitted in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) Complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: Examiner Luca Caminati Examiner Mary Esteve Supervisor Martin Lefebvre Approved by Marc Steinberg 2020 Rebecca Duclos Taylor iii Abstract Overwhelmed and Underworked: Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative Miles Taylor This thesis proposes an artistic mode called aproductivity, which arises with the secular crisis of capitalism in the early 1970’s. It reads aproductivity as the aesthetic reification of Theodor Adorno’s negative dialectics, a peculiar form of philosophy that refuses to move forward, instead producing dialectics without synthesis. The first chapter examines the economic history aproductivity grows out of, as well as its relation to Francis Fukuyama’s concept of “The End of History.” After doing so, the chapter explores negative dialectics and aproductivity in relation to Adam Phillips’ concept of the transformational object. In the second chapter, the thesis looks at the Thomas Pynchon novel Inherent Vice (2009), as well as the 2014 Paul Thomas Anderson adaptation of the same name. -

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem -

Music in Thomas Pynchon's Mason & Dixon

ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): John Joseph Hess Affiliation(s): Independent Researcher Title: Music in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon Date: 2014 Volume: 2 Issue: 2 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/75 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/orbit.v2.2.75 Abstract: Through Pynchon-written songs, integration of Italian opera, instances of harmonic performance, dialogue with Plato’s Republic and Benjamin Franklin’s glass armonica performance, Mason & Dixon extends, elaborates, and investigates Pynchon’s own standard musical practices. Pynchon’s investigation of the domestic, political, and theoretical dimensions of musical harmony in colonial America provides the focus for the novel’s historical, political, and aesthetic critique. Extending Pynchon’s career-long engagement with musical forms and cultures to unique levels of philosophical abstraction, in Mason & Dixon’s consideration of the “inherent Vice” of harmony, Pynchon ultimately criticizes the tendency in his own fiction for characters and narrators to conceive of music in terms that rely on the tenuous and affective communal potentials of harmony. Music in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon John Joseph Hess Few readers of Thomas Pynchon would dispute William Vesterman’s claim that “poems and particularly songs, make up a characteristic part of Pynchon’s work: without them a reader’s experience would not be at 1 all the same.” While Vesterman was specifically interested in Pynchon’s poetic practice, Pynchon’s fifty year career as a novelist involves a sustained engagement with a range of musical effects. Music is a formal feature with thematic significance in Pynchon’s early short fiction and in every novel from V. -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

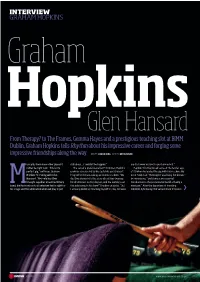

Interview Graham Hopkins

INTERVIEW GRAHAM HOPKINS Graham Hopkins Glen Hansard From Therapy? to The Frames, Gemma Hayes and a prestigious teaching slot at BIMM Dublin, Graham Hopkins tells Rhythm about his impressive career and forging some impressive friendships along the way WORDS: LOUISE KING PHOTOS: KEVIN NIXON usically, there is no other place I’d ridiculous… I couldn’t be happier.” my dad never wanted to push me into it.” rather be right now – this is my The son of a professional jazz drummer, Hopkins Hopkins’ first big break came at the tender age perfect gig,” enthuses Graham grew up surrounded by his dad’s kits and it wasn’t of 17, when he landed the gig with Irish rockers My Hopkins of touring with Glen long before he was taking an interest in them. “My Little Funhouse. “Overnight I was living the dream,” Hansard. “Not only has Glen dad Des always tells this story about him cleaning he reminisces, “and it was a very surreal brought together an extraordinary his drums next to my playpen, and me leaning over introduction to the professional world of being a Mband, but he trusts us to do what we feel is right for the side trying to hit them!” Hopkins chuckles. “But musician.” After the departure of founding his songs and the adrenaline when we play is just I actually ended up teaching myself to play, because member, Fyfe Ewing, the vacant drum throne in 42 | JULY 2013 WWW.RHYTHMMAGAZINE.CO.UK JULY 2013 | 43 INTERVIEW GRAHAM HOPKINS the mighty Therapy? beckoned, and Hopkins continued to hone his craft as the band headlined Graham has worked with arena tours and festivals around the world, and The Frames, Therapy?, Gemma Hayes and recorded three new studio albums together.