Educationally/Insufficient? an Analysis of the Availability & Educational Quality of Children’S E/I Programming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PBS Kids Resources: Age Levels and Educational Philosophy

PBS Kids Resources: Age Levels and Educational Philosophy Ages 4-8 yr. olds: ARTHUR's goal is to help foster an interest in reading and writing, and to encourage positive social skills. Only available in PBS LearningMedia — Ages 3-7 yr. olds: BTL is a lively, educational blend of phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, and other teaching methods for preschool, kindergarten, and first grade students. Several independent, scientifically-based read- ing research studies have shown that Between the Lions has a significant impact in in- Ages 2-5 yr. olds: "Make believe" is key to early childhood development. Ages 2-6 yr. olds: The series supports young children’s science learning by introducing sci- entific inquiry skills, teaching core science concepts and vocabulary, and preparing pre- schoolers for kindergarten and first grade science curriculum — all in whimsical style. Ages 3-7 yr. olds: Modeling of ten positive character traits that represent social and emo- tional challenges that children face and must master in the course of development. Ages 3-5 yr. olds: The goal of the series is to inspire children to explore science, engineer- ing, and math in the world around them. Ages 8-11 yr. olds: Every episode, game and activity is motivated by Cyber- chase characters and settings, and on a math concept centered on national standards. From tackling fractions in ancient Greece to using decimals to repair train tracks in Rail- road Repair, kids learn that math is everywhere and a useful tool for solving problems. Ages 2-4 yr. olds: This series, for a new generation of children, tells its engaging stories about the life of a preschooler using musical strategies grounded in Fred Rogers’ land- mark social-emotional curriculum. -

From Disney to Disaster: the Disney Corporation’S Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks

From Disney to Disaster: The Disney Corporation’s Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks BY Kelsey N. Reese Spring 2021 WMNST 492W: Senior Capstone Seminar Dr. Jill Wood Reese 2 INTRODUCTION The popularized phrase “celebrity trainwreck” has taken off in the last ten years, and the phrase actively evokes specified images (Doyle, 2017). These images usually depict young women hounded by paparazzi cameras that are most likely drunk or high and half naked after a wild night of partying (Doyle, 2017). These girls then become the emblem of celebrity, bad girl femininity (Doyle, 2017; Kiefer, 2016). The trainwreck is always a woman and is usually subject to extra attention in the limelight (Doyle, 2017). Trainwrecks are in demand; almost everything they do becomes front page news, especially if their actions are seen as scandalous, defamatory, or insane. The exponential growth of the internet in the early 2000s created new avenues of interest in celebrity life, including that of social media, gossip blogs, online tabloids, and collections of paparazzi snapshots (Hamad & Taylor, 2015; Mercer, 2013). What resulted was 24/7 media access into the trainwreck’s life and their long line of outrageous, commiserable actions (Doyle, 2017). Kristy Fairclough coined the term trainwreck in 2008 as a way to describe young, wild female celebrities who exemplify the ‘good girl gone bad’ image (Fairclough, 2008; Goodin-Smith, 2014). While the coining of the term is rather recent, the trainwreck image itself is not; in their book titled Trainwreck, Jude Ellison Doyle postulates that the trainwreck classification dates back to feminism’s first wave with Mary Wollstonecraft (Anand, 2018; Doyle, 2017). -

A Guide for Educators to Support the Weekend Morning TV Series

A Guide for Educators to Support the Weekend Morning TV Series TO EDUCATORS AND PARENTS "The All New Captain Kangaroo"—A Guide for Educators is designed to help educators and parents locate the educational components of each episode. The Storybook Corner section (page 4) includes a list of storybook titles that Captain Kangaroo will read throughout the CAPTAIN KANGAROO season—all of which tie into the theme of each episode. The grid (pages 14-15) will allow the Presented by Saban Entertainment, CURRICULUM AREAS reader to view the theme, manner/civility Inc., in association with Reading Music, Art, Science, lesson, educational goal Is Fundamental® and The America Reading and Language Arts and learning objective, Reads Challenge AGE LEVELS as well as the focus of Ages 2-5 the Nature/Animal and & Storybook Corner he Captain is back! Captain Kangaroo, GRADE LEVELS segments, for each beloved icon of children's programming Pre-Kindergarten, episode. Tand television figure with whom millions Kindergarten of kids grew up, returns to usher a new gener * "The All New ation into a new millennium. EDUCATIONAL GOALS Captain Kangaroo" "The All New Captain Kangaroo" blends • To promote self-esteem, will trigger meaningful the best of the original show with new educa cooperative, pro-social classroom discussions tional goals and characters to create a fun, behavior and a positive "The All New Captain Kangaroo" or activities that are exciting and educational TV experience. attitude. airs weekly nationwide on Saturday sure to build and Veteran actor John McDonough, who has • To introduce the impor or Sunday morning. strengthen character. -

AETN Resource Guide for Child Care Professionals

AAEETTNN RReessoouurrccee GGuuiiddee ffoorr CChhiilldd CCaarree PPrrooffeessssiioonnaallss Broadcast Schedule PARENTING COUNTS RESOURCES A.M. HELP PARENTS 6:00 Between the Lions The resource-rich PARENTING 6:30 Maya & Miguel COUNTS project provides caregivers 7:00 Arthur and parents a variety of multi-level 7:30 Martha Speaks resources. Professional development 8:00 Curious George workshops presented by AETN provide a hands-on 8:30 Sid the Science Kid opportunity to explore and use the videos, lesson plans, 9:00 Super WHY! episode content and parent workshop formats. Once child 9:30 Clifford the Big Red Dog care providers are trained using the materials, they are able to 10:00 Sesame Street conduct effective parent workshops and provide useful 11:00 Dragon Tales handouts to parents and other caregivers. 11:30 WordWorld P.M. PARENTS AND CAREGIVERS 12:00 Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood CAN ASK THE EXPERTS 12:30 Big Comfy Couch The PBS online Expert Q&A gives 1:00 Reading Rainbow parents and caregivers the opportunity to 1:30 Between the Lions ask an expert in the field of early childhood 2:00 Caillou development for advice. The service includes information 2:30 Curious George about the expert, provides related links and gives information 3:00 Martha Speaks about other experts. Recent subjects include preparing 3:30 Wordgirl children for school, Internet safety and links to appropriate 4:00 Fetch with Ruff Ruffman PBS parent guides. The format is easy and friendly. To ask 4:30 Cyberchase the experts, visit http://www.pbs.org/parents/issuesadvice. STAY CURRENT WITH THE FREE STATIONBREAK NEWS FOR EDUCATORS AETN StationBreak News for Educators provides a unique (and free) resource for parents, child care professionals and other educators. -

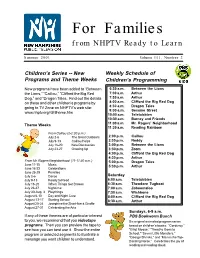

For Families from NHPTV Ready to Learn

For Families from NHPTV Ready to Learn Summer 2001 Volume III, Number 2 Children’s Series -- New Weekly Schedule of Programs and Theme Weeks Children’s Programming New programs have been added to “Between 6:30 a.m. Between the Lions the Lions,” “Caillou,” “Clifford the Big Red 7:00 a.m. Arthur Dog,” and “Dragon Tales. Find out the details 7:30 a.m. Arthur on these and other children’s programs by 8:00 a.m. Clifford the Big Red Dog going to TV Zone on NHPTV’s web site: 8:30 a.m. Dragon Tales 9:00 a.m. Sesame Street www.nhptv.org/rtl/rtlhome.htm 10:00 a.m. Teletubbies 10:30 a.m. Barney and Friends Theme Weeks 11:00 a.m. Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood 11:30 a.m. Reading Rainbow From Caillou (2-2:30 p.m.) July 2-6 The Great Outdoors 2:00 p.m. Caillou July 9-13 Caillou Helps 2:30 p.m. Noddy July 16-20 New Discoveries 3:00 p.m. Between the Lions July 23-27 Growing Up 3:30 p.m. Zoom 4:00 p.m. Clifford the Big Red Dog 4:30 p.m. Arthur From Mr. Rogers Neighborhood (11-11:30 a.m.) 5:00 p.m. Dragon Tales June 11-15 Music 5:30 p.m. Arthur June 18-22 Celebrations June 25-29 Families July 2-6 Dance Saturday July 9-13 Ready to Read 6:00 a.m. Teletubbies July 16-20 When Things Get Broken 6:30 a.m. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

November (English)

Dennis-Yarmouth Title I From the Title I Coordinator Volume 1, Issue ii recommendations on books for you. ◊ Set aside time for reading. Designate a time November, 2017 of day when family members can read for pleasure. Make reading a part of your family routine. ◊Make reading special. Children should feel as if having a book is special. Help them create a space for storing their books. However, if your child doesn’t show an interest or strong ability in read- ing, be patient, but do not give up. Reading should be viewed as an enjoyable activity. ◊ Use your local library. One of the best resources you will have as a parent is access to your community’s library. It costs nothing to borrow books. Many libraries offer story hours and other fun literacy activities. Make visits to your library a routine activity. Yarmouth Libraries South Yarmouth—508-7600-4820 f you have any questions, please Parents play a specific role in their child’s literacy Yarmouthport—508-362-3717 contact me, Cookie Stewart, at 508- 778-7599 ext. 6204 or development by: creating a literacy-rich environ- West Yarmouth—508-775-5206 [email protected] ment; sharing reading and writing activities; acting Dennis Libraries as reading models; and demonstrating attitudes Jacob Sears—508-385-8151 toward education. A strong educational environ- Dennis Public Library—508-760-6219 ment at home can be a major factor in reinforcing the home-school connection. Limit television time. Monitior program selection Read to Your Child for your children. Discuss programs with them. -

The Relations of Parental Acculturation, Parental Mediation, and Children's Educational Television Program Viewing in Immigrant Families Yuting Zhao

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Relations of Parental Acculturation, Parental Mediation, and Children's Educational Television Program Viewing in Immigrant Families Yuting Zhao Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION THE RELATIONS OF PARENTAL ACCULTURATION, PARENTAL MEDIATION, AND CHILDREN’S EDUCATIONAL TELEVISION PROGRAM VIEWING IN IMMIGRANT FAMILIES By YUTING ZHAO A Thesis submitted to the Department of Educational Psychology and Learning Systems in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Yuting Zhao defended this thesis on December 7th, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Beth M. Phillips Professor Directing Thesis Alysia D. Roehrig Committee Member Yanyun Yang Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... vii -

In-School Mentoring Activity Manual

In-School Mentoring Activity Manual Introducing the Manual and the value of Play Welcome to the In-School Mentoring Program. We hope you are as excited as we are about participating in a program designed to help boost kids’ self-confidence. Sometimes mentors and mentees can get stumped for activities they can do together in one hour. This manual serves as a resource guide. Here you will find new activities, games and craft ideas. Also provided are tried and true hints and advice from current mentors in the field. General information on children’s stages of development is included. This background information may help you to chose a more accurate game to play with your mentee based on his/her skill level, or may remind you of the outside factors your mentee is dealing with at his/her age. Mentors often ask “How does play activity benefit mentees?” Here is a brief response on the value of play… “On the playground of life, game playing equips each of us with the “rules of the game.” As youngsters, games taught us how to work together, to accommodate, and to help one another. Through playful moments, children can act out real-life situations. In imagined contexts, they can learn how to solve problems, look for options, and resolve conflicts. By winning or losing at games, children experience the real world but in less harsh fashion. Children learn about their environment and how to relate to other children, as well as grown-ups. They learn about healthy competition and about trying to do their best. -

Disney Letar Ny Stjärna I Sverige

Disney letar ny stjärna i Sverige I höst är det premiär för ungdomsserien Violetta på Disney Channel i Sverige. Tv-serien har på kort tid etablerat sig som ett ungdomsfenomen på flera internationella marknader där programmets musik spelas flitigt även utanför tv-rutan. Inför premiären i Sverige söker Disney nu tillsammans med Universal MusiC oCh Spinnup en lokal talang för att spela in seriens svenska ledmotiv. Tv-serien Violetta följer huvudpersonen med samma namn i allt det som hör tonårstiden till; kompisar, kärlek, familj och drömmar om framtiden. En stor del av historien utspelar sig på den sång- och dansskola som ’Violetta’ går på och musik är en integrerad del i berättelsen där varje avsnitt innehåller flera specialskrivna låtar. - Det känns fantastiskt roligt att Violetta snart kommer hit. Efter succéerna med Hannah Montana och High School Musical har vi väntat på nästa serie med lika stor potential och att döma av vad vi sett på andra marknader har vi nu det i Violetta. I ett sådant sammanhang känns det extra kul att kunna vidareutveckla vårt samarbete med Universal Music för att hitta rätt sångtalang, säger Anna Glanmark, Marknadsdirektör, The Walt Disney Company Nordic. Arbetet med att identifiera rätt talang för det svenska ledmotivet görs i samarbete med Universal Music genom Spinnup som är en digital distributionstjänst för osignade artister. Det som gör Spinnup unikt är att de osignade artisterna som distribuerar sin musik via tjänsten har tillgång till ett dedikerat team av Spinnup Scouter som söker nya talanger att jobba med, nu även med fokus att hitta Disneys nya stjärna. -

On the Disney Channel's Hannah Mont

Tween Intimacy and the Problem of Public Life in Children’s Media: “Having It All” on the Disney Channel’s Hannah Montana Tyler Bickford Contradictions of public participation pervade the everyday lives of con- temporary children and those around them. In the past two decades, the children’s media and consumer industries have expanded and dramat- ically transformed, especially through the development and consolida- tion of “tweens”—people ages nine to thirteen, not yet “teenagers” but no longer quite “children”—as a key consumer demographic (Cook and Kaiser 2004). Commentators increasingly bemoan the destabilization of age identities, pointing to children’s purportedly more “mature” taste in music, clothes, and media as evidence of a process of “kids getting older younger” (Schor 2004), and to adults’ consumer practices as evidence of their infantilization (Barber 2007). Tween discourses focus especially on girls, for whom the boundary between childhood innocence and adolescent or adult independence is fraught with moral panic around sexuality, which only heightens anxieties about changing age identities. Girls’ consumption and media participation increasingly involve per- formances in the relatively public spaces of social media, mobile media, and the Internet (Banet-Weiser 2011; Bickford, in press; Kearney 2007), so the public sphere of consumption is full of exuberant participation in mass-mediated publics. Beyond literal performances online and on social media, even everyday unmediated consumption—of toys, clothes, food, and entertainment—is fraught with contradictory meanings invoking children’s public image as symbols of domesticity, innocence, and the family and anxiety about children’s intense affiliation with peer com- munities outside the family (Pugh 2009). -

INSTITUTION Congress of the US, Washington, DC. House Committee

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 303 136 IR 013 589 TITLE Commercialization of Children's Television. Hearings on H.R. 3288, H.R. 3966, and H.R. 4125: Bills To Require the FCC To Reinstate Restrictions on Advertising during Children's Television, To Enforce the Obligation of Broadcasters To Meet the Educational Needs of the Child Audience, and for Other Purposes, before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives, One Hundredth Congress (September 15, 1987 and March 17, 1988). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Energy and Commerce. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 354p.; Serial No. 100-93. Portions contain small print. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) -- Viewpoints (120) -- Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Advertising; *Childrens Television; *Commercial Television; *Federal Legislation; Hearings; Policy Formation; *Programing (Broadcast); *Television Commercials; Television Research; Toys IDENTIFIERS Congress 100th; Federal Communications Commission ABSTRACT This report provides transcripts of two hearings held 6 months apart before a subcommittee of the House of Representatives on three bills which would require the Federal Communications Commission to reinstate restrictions on advertising on children's television programs. The texts of the bills under consideration, H.R. 3288, H.R. 3966, and H.R. 4125 are also provided. Testimony and statements were presented by:(1) Representative Terry L. Bruce of Illinois; (2) Peggy Charren, Action for Children's Television; (3) Robert Chase, National Education Association; (4) John Claster, Claster Television; (5) William Dietz, Tufts New England Medical Center; (6) Wallace Jorgenson, National Association of Broadcasters; (7) Dale L.