Keeping Children Safe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Framework for Considering the Best Interests of Unaccompanied Children May 2016

Subcommittee on Best Interests of the Interagency Working Group on Unaccompanied and Separated Children PREPARED BY: with support from: FRAMEWORK FOR at the University of Chicago the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation CONSIDERING THE BEST INTERESTS and in collaboration with: OF UNACCOMPANIED CHILDREN MAY 2016 Subcommittee on Best Interests of the Interagency Working Group on Unaccompanied and Separated Children FRAMEWORK FOR CONSIDERING THE BEST INTERESTS OF UNACCOMPANIED CHILDREN MAY 2016 PREPARED BY: with support from: at the University of Chicago the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and in collaboration with: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The creation of this document, Framework for Considering the Best Interests of Unaccompa- nied Children, was made possible by the generous support of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the leadership of John Slocum and Tara Magner. This document represents the culmination of three years of work by the Subcommittee on Best Interests of the Interagency Working Group on Unaccompanied and Separated Children. It is intended to be a practical, step-by-step guide for considering the best interests of individual children within the confnes of existing law. This project was premised on collaboration between federal agencies and non-governmental organizations and would not have been possible without the stewardship of Professor Andrew Schoenholtz of the Georgetown University Law Center. Professor Schoenholtz moderated each of the Subcommittee meetings, lending a critical tone of -

Mapping Experiences and Research About Unaccompanied Refugee Minors in Sweden and Other Countries

IZA DP No. 10143 Mapping Experiences and Research about Unaccompanied Refugee Minors in Sweden and Other Countries Aycan Çelikaksoy Eskil Wadensjö August 2016 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Mapping Experiences and Research about Unaccompanied Refugee Minors in Sweden and Other Countries Aycan Çelikaksoy SOFI, Stockholm University Eskil Wadensjö SOFI, Stockholm University and IZA Discussion Paper No. 10143 August 2016 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. -

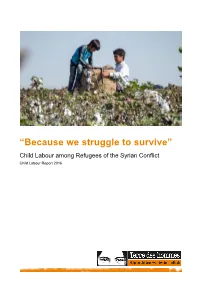

'Because We Struggle to Survive'

“Because we struggle to survive” Child Labour among Refugees of the Syrian Conflict Child Labour Report 2016 Disclaimer terre des hommes Siège | Hauptsitz | Sede | Headquarters Avenue de Montchoisi 15, CH-1006 Lausanne T +41 58 611 06 66, F +41 58 611 06 77 E-mail : [email protected], CCP : 10-11504-8 Research support: Ornella Barros, Dr. Beate Scherrer, Angela Großmann Authors: Barbara Küppers, Antje Ruhmann Photos : Front cover, S. 13, 37: Servet Dilber S. 3, 8, 12, 21, 22, 24, 27, 47: Ollivier Girard S. 3: Terre des Hommes International Federation S. 3: Christel Kovermann S. 5, 15: Terre des Hommes Netherlands S. 7: Helmut Steinkeller S. 10, 30, 38, 40: Kerem Yucel S. 33: Terre des hommes Italy The study at hand is part of a series published by terre des hommes Germany annually on 12 June, the World Day against Child Labour. We would like to thank terre des hommes Germany for their excellent work, as well as Terre des hommes Italy and Terre des Hommes Netherlands for their contributions to the study. We would also like to thank our employees, especially in the Middle East and in Europe for their contributions to the study itself, as well as to the work of editing and translating it. Terre des hommes (Lausanne) is a member of the Terre des Hommes International Federation (TDHIF) that brings together partner organisations in Switzerland and in other countries. TDHIF repesents its members at an international and European level. First published by terre des hommes Germany in English and German, June 2016. -

The Legal Status of Unaccompanied Children Within International, European and National Frameworks Protective Standards Vs

PUCAFREU PROJECT: PROMOTING UNPROTECTED UNACCOMPANIED CHILDREN’S ACCESS TO THEIR FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS IN THE EUROPEAN UNION PUCAFREU Promoting unaccompanied Children’s Access to Fundamental Rights in the European Union Co-funded by the European Union’s Fundamental Rights and Citizenship Programme THE LEGAL STATUS OF UNACCOMPANIED CHILDREN ////////////////////////////////////////////// WITHIN INTERNATIONAL, EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL FRAMEWORKS PROTECTIVE STANDARDS VS. RESTRICTIVE IMPLEMENTATION EDITED BY DANIEL SENOVILLA & PHILIPPE LAGRANGE Published in 2011 within the framework of the PUCAFREU Project « Promoting unaccompanied children’s access to fundamental rights in the European Union ». This project has been co-funded by the European Union’s Fundamental Rights and Citizenship Programme. The contents, facts and opinions expressed throughout this publication are the responsibility of the authors and do not commit neither the European Union Institutions nor any of the other public or private Institutions involved in the PUCAFREU Project. Cover and interior design and formatting: Daniel Gazeau Language review: Robert Parker, English Coaching THE LEGAL STATUS OF UNACCOMPANIED CHILDREN WITHIN INTERNATIONAL, EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL FRAMEWORKS PROTECTIVE STANDARDS VS. RESTRICTIVE IMPLEMENTATION EDITED BY DANIEL SENOVILLA & PHILIPPE LAGRANGE PUCAFREU PROJECT: Promoting unprotected PUCAFREU unaccompanied children’s access to their Promoting unaccompanied Children’s Access to Fundamental Rights in the European Union fundamental rights in the European -

Return of Foreign Unaccompanied Minors

POLICY PAPER RETURN OF FOREIGN UNACCOMPANIED MINORS Pre-publishing release March 2007 Terre des hommes Foundation – Pre-publishing releas e March 2007 CONTENT I. Introduction II. Set of Principles and Criteria 4 II.1.a The principle of Durable Solution 4 II.1.b General considerations in deciding in favor or against return 4 II.2 Steps to be followed 6 II.2.a Interviewing the child, documenting information and tracing the family 6 II.2.b Assessment in the country of origin 7 II.2.c Assessment in the host country 9 II.2.d The FUM’s opinion 10 III. Framework for Tdh actions 12 III.1 Advocacy and Networking 12 III.2 Field activities of Tdh and/or partners 14 III.2.a Durable solution 14 III.2.b Enforcement of return decision 14 III.3. Capacity building 16 Bibliography 17 Policy Paper on Issues related to Return of Foreign Unaccompanied Minors 2 Terre des hommes Foundation – Pre-publishing releas e March 2007 Introduction The protection of the rights of foreign unaccompanied children (FUM) constitutes an area of concern for Terre des hommes, as a child rights organization. While many issues arise in this context, any of them bearing its own complexity, the scope of the proposed Policy is limited to the involvement of the organization in issues related to the return, or not, of FUM in their countries of origin. The Policy will provide a set of criteria and procedures to be respected within Terre des hommes in its recommendations to the authorities regarding the durable solution for a FUM. -

Information for the UPR Review

EMBARGOED UNTIL 08th of September 2008 Joint NGO Submission – CHILD RIGHTS – UPR on FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY – February 2009 Submitted by: Aktion Courage, AFET – Federal Association of Child Rearing Support, Children’s Charity of Germany, European Master in Children’s Rights, Federal Association of Single Mothers and Fathers, Federal Association of Unaccompanied Minor Refugees, German Association for Children in Hospital, German Children’s Aid, International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) e.V., Kindernothilfe, Naturfreundejugend Deutschland, Physicians in Social Responsibility (German Section), Pressure Group for Maintenance and Family Rights Inc., PRO ASYL, terre des hommes, Workinggroup Refugee Children within the Centres for Refugees and Torture Survivors in Germany/BAFF. For further information, please contact: Barbara Dünnweller, Kindernothilfe: [email protected] 1. We offer the following submission on the situation of child rights in the FEDERAL REPUBLIC of GERMANY for consideration as part of the Universal Periodic Review in February 2009. The submission has particular regard to the government’s reservation to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). 2. Germany is state party to the CRC (1992) the Optional Protocol on Children in Armed Conflict (2004), and has signed the Optional Protocol on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography (signed 2000). I. Reservations to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) 3. Germany ratified the UN-CRC on 6 March 1992, and submitted its first report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child in 1994, the second one in 2003. The third and fourth report are now in preparation to be submitted as one single report in 2009. -

Unaccompanied Minors the European Union

THE RECEPTION AND CARE OF UNACCOMPANIED MINORS IN EIGHT COUNTRIES OF THE EUROPEAN UNION COMPARATIVE STUDY AND HARMONISATION PROSPECTS Spain - France- Great Britain - Greece – Hungary - Italy – Romania - Sweden FINAL REPORT – DECEMBER 2010 Project co-funded by the European Union’s Fundamental Rights and Citizenship programme This study has been carried out under the supervision of Laurent DELBOS (France terre d’asile), project coordinator, On the basis of research done by Marine CARLIER (France terre d’asile) Maria de DONATO (Consiglio Italiano per i Rifugiati) Miltos PAVLOU (Institute for Rights, Equality and Diversity) In collaboration with Matina POULOU (i-RED), Antonio GALLARDO & Pilar MARTIN (MPDL - El Movimiento por la Paz), Nicoletta PALMIERI and Eleonora BENASSI (CIR) The complete report (French, English) and the summaries (French, English, Italian, Greek) are available at http://www.france-terre-asile.org/childrenstudies The opinions expressed in this document are those of its authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission 2 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 6 Main abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. 7 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 9 I. Knowledge of the -

Unaccompanied Minors: Quantitative Aspects and Reception, Return and Integration Policies. Analysis of the Italian Case For

Unaccompanied Minors: Quantitative Aspects and Reception, Return and Integration Policies. Analysis of the Italian Case for a Comparative Study at the EU Level Edited by the Italian National Contact Point within EUROPEAN MIGRATION NETWORK EMN IDOS Research Centre with the support of the Italian Ministry of Interior www.emnitaly.it ROME 2009 Unaccompanied Minors: Quantitative Aspects and Reception, Return and Integration Policies. Analysis of the Italian Case for a Comparative Study at the EU Level Edited by Franco Pittau, Antonio Ricci, Laura Ildiko Timsa (IDOS Research Centre) with the collaboration of Caritas/Migrantes Statistical Dossier on Immigration Translation by Claudia Di Sciullo and Alessandro Fuligni Table of contents Introduction: purpose and methodology p.3 Motivations for seeking entry into Italy p.7 Entry procedures, including border control p.11 Reception procedures and integration measures p.23 Return procedures p.30 Concluding remarks: best practice and lessons learned p.35 Annex I: Bibliography p.38 Annex II: Legislation p.40 2 1. INTRODUCTION: PURPOSE AND METHODOLOGY On May 14, 2008 the Council of the European Union took a Decision to establish the launch of a European Migration Network (2008/381/EC)1, internationally known as EMN (the English acronym of the Network). The objective of this Network consists in responding to the information needs of both EU and national institutions by providing up-to-date, objective, reliable and comparable information on migration and asylum: therefore, it is expected to follow and support the EU policies and provide the general public with broader information on these topics. The Italian Ministry of Interior has commissioned Caritas Italy - and consequently the IDOS Research Centre (which draws up for Caritas and Migrantes the well-known annual report called Statistical Dossier on Immigration) - to implement these activities. -

The Rise and Fall of the ERPUM Pilot Tracing the European Policy Drive to Deport Unaccompanied Minors

WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 108 The rise and fall of the ERPUM pilot Tracing the European policy drive to deport unaccompanied minors Dr Martin Lemberg-Pedersen University of Copenhagen [email protected] March 2015 Refugee Studies Centre Oxford Department of International Development University of Oxford Working Paper Series The Refugee Studies Centre (RSC) Working Paper Series is intended to aid the rapid distribution of work in progress, research findings and special lectures by researchers and associates of the RSC. Papers aim to stimulate discussion among the worldwide community of scholars, policymakers and practitioners. They are distributed free of charge in PDF format via the RSC website. Bound hard copies of the working papers may also be purchased from the Centre. The opinions expressed in the papers are solely those of the author/s who retain the copyright. They should not be attributed to the project funders or the Refugee Studies Centre, the Oxford Department of International Development or the University of Oxford. Comments on individual Working Papers are welcomed, and should be directed to the author/s. Further details may be found at the RSC website (www.rsc.ox.ac.uk). 1 RSC WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 108 Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 Methodology 4 3 Theoretical frameworks 5 4 The ERPUM pilot 6 5 Family tracing, reception facilities and motivating child-returns 7 6 National legal reforms and the return agenda 11 7 Political debates and public scrutiny into ERPUM 15 8 Immigration trends of unaccompanied minors to the ERPUM -

Seeking Asylum Alone: Using the Best Interests of the Child Principle to Protect Unaccompanied Minors Joyce Koo Dalrymple

Boston College Third World Law Journal Volume 26 Issue 1 Black Children and Their Families in the 21st Article 9 Century: Surviving the American Nightmare or Living the American Dream? 1-1-2006 Seeking Asylum Alone: Using the Best Interests of the Child Principle to Protect Unaccompanied Minors Joyce Koo Dalrymple Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj Part of the Immigration Law Commons, and the Juveniles Commons Recommended Citation Joyce Koo Dalrymple, Seeking Asylum Alone: Using the Best Interests of the Child Principle to Protect Unaccompanied Minors, 26 B.C. Third World L.J. 131 (2006), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/ twlj/vol26/iss1/9 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Third World Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEEKING ASYLUM ALONE: USING THE BEST INTERESTS OF THE CHILD PRINCIPLE TO PROTECT UNACCOMPANIED MINORS Joyce Koo Dalrymple* Abstract: Every year about five thousand children under the age of eighteen enter the United States without legal guardians. These child- ren must meet the same substantive standards as adults in order to gain asylum. As children, they face unique difficulties because they may not understand the persecutor’s intent and may not be able to explain their experiences as persecution on account of one of the five enumerate asylum grounds. Furthermore, they must navigate a confusing legal system designed primarily for adults with limited English skills and without the assistance of government-appointed attorneys or guardian ad litems. -

The Admission of Unaccompanied Children Into the United States

The Admission of Unaccompanied Children into the United States Daniel J. Steinbock* For most of the twentieth century there have been, at any given time, millions of children endangered in or displaced from their na- tive countries by war, famine, natural disaster, civil strife, and perse- cution.' Since World War II, the United States has admitted thousands of children by themselves from crisis areas and refugee camps. Although these children constitute a relatively small per- centage of the total population admitted to the United States as per- manent residents and refugees, their vulnerability and the special requirements for their support, placement, and integration into so- ciety produce an impact out of proportion to their numbers. Children without a parent, guardian, or other adult who is legally responsible for them are sometimes referred to as "unaccompanied children." 2 Unaccompanied children have been admitted to the United States in two typical situations. The first is the evacuation of children from their own countries, in times of physical danger or persecution, separating them from their parents.3 Evacuation of * Associate Professor of Law, University of Toledo College of Law. The author served as education and border tracing coordinator with the International Rescue Com- mittee in refugee camps along the Thai-Cambodian border in 1980-81. Research for this article was supported by The University of Toledo Faculty Research Awards and Fellowships Program. The author would like to thank Joseph Edwards, Martha Lyons, Katherine Tracey, and Susan van der Klooster for their valuable research assistance; Rhoda Berkowitz, Richard Edwards, Laurie Jackson, and Nancy Schulz for their com- ments on earlier drafts; and Lee Mayer for her secretarial assistance. -

Approaches to Unaccompanied Minors Following Status Determination in Ireland

ESRI RESEARCH SERIES APPROACHES TO UNACCOMPANIED NUMBER 83 December 2018 MINORS FOLLOWING STATUS DETERMINATION IN IRELAND SARAH GROARKE AND SAMANTHA ARNOLD FO NCE R PO DE LI VI C E Y EMN Ireland is funded by the European Union's Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund and co- funded by the Department of Justice and Equality. APPROACHES TO UNACCOMPANIED MINORS FOLLOWING STATUS DETERMINATION IN IRELAND Sarah Groarke Samantha Arnold December 2018 RESEARCH SERIES NUMBER 83 Study completed by the Irish National Contact Point of the European Migration Network (EMN), which is financially supported by the European Union and the Irish Department of Justice and Equality. The EMN was established via Council Decision 2008/381/EC. Available to download from www.emn.ie The Economic and Social Research Institute Whitaker Square, Sir John Rogerson’s Quay, Dublin 2 ISBN: 978-0-7070-0476-1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26504/rs83 This Open Access work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. THE EUROPEAN MIGRATION NETWORK The aim of the European Migration Network (EMN) is to provide up-to-date, objective, reliable and comparable information on migration and asylum at Member State and EU levels with a view to supporting policymaking and informing the general public. The Irish National Contact Point of the European Migration Network, EMN Ireland, sits within the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI). ABOUT THE ESRI The mission of the Economic and Social Research Institute is to advance evidence- based policymaking that supports economic sustainability and social progress in Ireland.