'It Must Flow' a Life in Theatre Habib Tanvir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Rabindra Sangeet

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION NET BUREAU Subject: MUSIC Code No.: 16 SYLLABUS Hindustani (Vocal, Instrumental & Musicology), Karnataka, Percussion and Rabindra Sangeet Note:- Unit-I, II, III & IV are common to all in music Unit-V to X are subject specific in music www.careerindia.com -1- Unit-I Technical Terms: Sangeet, Nada: ahata & anahata , Shruti & its five jaties, Seven Vedic Swaras, Seven Swaras used in Gandharva, Suddha & Vikrit Swara, Vadi- Samvadi, Anuvadi-Vivadi, Saptak, Aroha, Avaroha, Pakad / vishesa sanchara, Purvanga, Uttaranga, Audava, Shadava, Sampoorna, Varna, Alankara, Alapa, Tana, Gamaka, Alpatva-Bahutva, Graha, Ansha, Nyasa, Apanyas, Avirbhav,Tirobhava, Geeta; Gandharva, Gana, Marga Sangeeta, Deshi Sangeeta, Kutapa, Vrinda, Vaggeyakara Mela, Thata, Raga, Upanga ,Bhashanga ,Meend, Khatka, Murki, Soot, Gat, Jod, Jhala, Ghaseet, Baj, Harmony and Melody, Tala, laya and different layakari, common talas in Hindustani music, Sapta Talas and 35 Talas, Taladasa pranas, Yati, Theka, Matra, Vibhag, Tali, Khali, Quida, Peshkar, Uthaan, Gat, Paran, Rela, Tihai, Chakradar, Laggi, Ladi, Marga-Deshi Tala, Avartana, Sama, Vishama, Atita, Anagata, Dasvidha Gamakas, Panchdasa Gamakas ,Katapayadi scheme, Names of 12 Chakras, Twelve Swarasthanas, Niraval, Sangati, Mudra, Shadangas , Alapana, Tanam, Kaku, Akarmatrik notations. Unit-II Folk Music Origin, evolution and classification of Indian folk song / music. Characteristics of folk music. Detailed study of folk music, folk instruments and performers of various regions in India. Ragas and Talas used in folk music Folk fairs & festivals in India. www.careerindia.com -2- Unit-III Rasa and Aesthetics: Rasa, Principles of Rasa according to Bharata and others. Rasa nishpatti and its application to Indian Classical Music. Bhava and Rasa Rasa in relation to swara, laya, tala, chhanda and lyrics. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Tapassu and Bhallika of Orissa, Their Historicity and Nativity (Fresh Evidence from Recent Archaeological Explorations and Excavations)

Orissa Review * November - 2007 Tapassu and Bhallika of Orissa, Their Historicity and Nativity (Fresh Evidence from Recent Archaeological Explorations and Excavations) Gopinath Mohanty, Dr. C. B. Patel, D. R. Pradhan & Dr. B. Tripathy Inscription - Kesa Thupa The historicity and nativity of Tapassu and Bhallika, others. Most of the scholars are of the opinion the two merchant brothers of Utkala who became that Utkala of the epic and Puranas is the same the first disciples of Lord Buddha are shrouded as 'Ukkala' or 'Okkala' of the Pali literature. in mystery. Utkal was a very ancient country. In According to Majjhima Nikaya, Vassa and Buddhist literature it is described as 'Ukkala' or Bhanna are the two tribes of Ukkala who 'Okkala'. In the Brahmincal literature we find professed a type of religion called Ahetuvada, copious depiction of Utkala to have been located Akiriyavada and Natthikavada. These two tribes in the southern region of extended Vindyan range later on are known to have embraced Buddhism along with Mekalas, Kalingas, Andhras and preached by Lord Buddha. Tapassu and Bhallika 1 Orissa Review * November - 2007 Inscriptioin - Bhekku Tapussa Danam (variedly described as Tapussa and Bhalluka or of India. Under this historical backdrop, we have Bhalliya) are ascribed to Vassa and Bhanna tribes to identify the original home land of Tapassu and of ancient Utkala. The two merchant brothers Bhallika basing on the fresh archaeological became so widely popular in Buddhist world that evidence. they were represented in various garbs in various Now, the Department of Culture, Govt. of countries. The Burmese legends speak Tapassu Orissa is making extensive archaeological (Tapoosa) & Bhallika (Palekat) as the residents exploration and excavations in various parts of of the city of Okkalaba in the Irrawaddy valley. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Reconstructing the Indian Filmography

ASHISH RAJADHYAKSHA Reconstructing The Indian Filmography Sitara Devi and the Indian filmographer A n apocryphal story has V.A.K. Ranga Rao, the irascible collector of music and authority on South Indian cinema, offering an open challenge. It seems he saw Mother India on his television one night and was taken aback to see Sitara Devi’s name in the acting credits. The open challenge was to anyone who could spot Sitara Devi anywhere in the film. And, he asked, if she was not in the film, to answer two questions. First, what happened? Was something filmed with her and cut out? If so, when was this cut out? Almost more important: what to do with Sitara Devi’s filmography? Should Mother India feature in that or not? Such a problem would cut deep among what I want to call the classic years of the Indian filmographers. The Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema decided to include Sitara Devi’s name in its credits, mainly because its own key source for Hindi credits before 1970 was Firoze Rangoonwala’s iconic Indian Filmography, Silent and Hindi Film: 1897-1969, published in 1970 and Har Mandir Singh ‘Hamraaz’s somewhat different, equally legendary Hindi Film Geet Kosh which came out with the first edition of its 1951-60 listings in 1980. The Singh Geet Kosh tradition would provide bulwark support both on JOURNAL OF THE MOVING IMAGE 13 its own but also through a series of other Geet Koshes by Harish Raghuvanshi on Gujarati, Murladhar Soni on Rajasthani and many others. Like Ranga Rao, Singh and the other Geet Kosh editors have had his own variations of the Sitara Devi problem: his focus was on songs, and he was coming across major discrepancies between film titles, their publicity material and record listings. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

India Country Name India

TOPONYMIC FACT FILE India Country name India State title in English Republic of India State title in official languages (Bhārat Gaṇarājya) (romanized in brackets) भारत गणरा煍य Name of citizen Indian Official languages Hindi, written in Devanagari script, and English1 Country name in official languages (Bhārat) (romanized in brackets) भारत Script Devanagari ISO-3166 code (alpha-2/alpha-3) IN/IND Capital New Delhi Population 1,210 million2 Introduction India occupies the greater part of South Asia. It was part of the British Empire from 1858 until 1947 when India was split along religious lines into two nations at independence: the Hindu-majority India and the Muslim-majority Pakistan. Its highly diverse population consists of thousands of ethnic groups and hundreds of languages. Northeast India comprises the states of Arunāchal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghālaya, Mizoram, Nāgāland, Sikkim and Tripura. It is connected to the rest of India through a narrow corridor of the state of West Bengal. It shares borders with the countries of Nepal, China, Bhutan, Myanmar (Burma) and Bangladesh. The mostly hilly and mountainous region is home to many hill tribes, with their own distinct languages and culture. Geographical names policy PCGN policy for India is to use the Roman-script geographical names found on official India-produced sources. Official maps are produced by the Survey of India primarily in Hindi and English (versions are also made in Odiya for Odisha state, Tamil for Tamil Nādu state and there is a Sanskrit version of the political map of the whole of India). The Survey of India is also responsible for the standardization of geographical names in India. -

Criterion an International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165

The Criterion www.the-criterion.com An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Revitalizing the Tradition: Mahesh Dattani’s Contribution to Indian English Drama Farah Deeba Shafiq M.Phil Scholar Department of English University of Kashmir Indian drama has had a rich and ancient tradition: the natyashastra being the oldest of the texts on the theory of drama. The dramatic form in India has worked through different traditions-the epic, the folk, the mythical, the realistic etc. The experience of colonization, however, may be responsible for the discontinuation of an indigenous native Indian dramatic form.During the immediate years following independence, dramatists like Mohan Rakesh, Badal Sircar, Girish Karnad, Vijay Tendulkar, Dharamvir Bharati et al laid the foundations of an autonomous “Indian” aesthetic-a body of plays that helped shape a new “National” dramatic tradition. It goes to their credit to inaugurate an Indian dramatic tradition that interrogated the socio-political complexities of the nascent Indian nation. However, it’s pertinent to point out that these playwrights often wrote in their own regional languages like Marathi, Kannada, Bengali and Hindi and only later translated their plays into English. Indian English drama per se finds its first practitioners in Shri Aurobindo, Harindarnath Chattopadhyaya, and A.S.P Ayyar. In the post- independence era, Asif Curriumbhoy (b.1928) is a pioneer of Indian English drama with almost thirty plays in his repertoire. However, owing to the spectacular success of the Indian English novel, Drama in English remained a minor genre and did not find its true voice until the arrival of Mahesh Dattani. -

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION 004 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Ward

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 004 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 11/H/5 PAIK PARA ROW KOL 37 ABHIJEET RUDRA BANAMALI RUDRA 3 1 4 1 2 61/3 B T ROAD ABHIJIT THAKUR T THAKUR 3 2 5 2 3 1/H/29 SARBAKHAN ROAD ABHIRAM MAITI LT NAGENDRA NATH MAITI 2 3 5 3 4 B/1/H/5 R.M.RD,KOL-37 ADALAT RAI LATE BABULAL RAI 3 1 4 4 5 18 DUMDUM ROAD ADHIR BARUI LATE ABINAS BARUI 1 2 3 5 6 SABAKHAN ROAD KOL-37 1/H/11 SABAKHAN ROAD KOL-37 ADHIR CHANDRA KARMAKAR LT PALAN CH KARMAKAR 4 2 6 6 7 1/B/H/1 UMAKANTA SEN LANE,KOL-30 ADHIR HALDER LATE SITA NATH HALDER 5 1 6 7 8 21/39 DUM DUM ROAD ADHIR SARKAR LT.ABHYA SARKAR 3 2 5 8 9 DEWAN BAGAN 11/H/5 PAIK PARA RD. AJAY DAS LT BISWANATH DAS 2 2 4 9 10 RANI HARSHAMUKHEE ROAD 49/H/1B RANI HARSHAMUKHEE ROAD AJAY YADAV LT SANKAR PRASAD YADAV 1 3 4 10 11 R.M. ROAD KOL-37 13/3 R.M. ROAD KOL-37 AJIM AKHTAR LT NABIR RASUL 2 4 6 11 12 GOSHALA 26/59 DUMDUM ROAD,KOL-2 AJIT BALMIKI LATE DHARMA BALMIKI 3 2 5 12 13 9/4 RANI BRUNCH ROAD KOL 2 AJIT DEY LT ANANTA DEY 1 3 4 13 14 1/B UMAKANTA SEN LANE AJIT KR. -

Annual Return

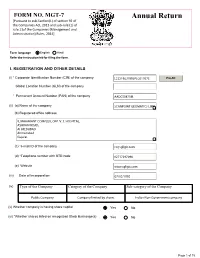

FORM NO. MGT-7 Annual Return [Pursuant to sub-Section(1) of section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and sub-rule (1) of rule 11of the Companies (Management and Administration) Rules, 2014] Form language English Hindi Refer the instruction kit for filing the form. I. REGISTRATION AND OTHER DETAILS (i) * Corporate Identification Number (CIN) of the company Pre-fill Global Location Number (GLN) of the company * Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the company (ii) (a) Name of the company (b) Registered office address (c) *e-mail ID of the company (d) *Telephone number with STD code (e) Website (iii) Date of Incorporation (iv) Type of the Company Category of the Company Sub-category of the Company (v) Whether company is having share capital Yes No (vi) *Whether shares listed on recognized Stock Exchange(s) Yes No Page 1 of 15 (a) Details of stock exchanges where shares are listed S. No. Stock Exchange Name Code 1 (b) CIN of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Pre-fill Name of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Registered office address of the Registrar and Transfer Agents (vii) *Financial year From date 01/04/2020 (DD/MM/YYYY) To date 31/03/2021 (DD/MM/YYYY) (viii) *Whether Annual general meeting (AGM) held Yes No (a) If yes, date of AGM (b) Due date of AGM (c) Whether any extension for AGM granted Yes No II. PRINCIPAL BUSINESS ACTIVITIES OF THE COMPANY *Number of business activities 1 S.No Main Description of Main Activity group Business Description of Business Activity % of turnover Activity Activity of the group code Code company J J8 III. -

3Rd All India Media Educators' Conference-2018 on Power of Media and Technology: Shaping the Future

CONFERENCE REPORT 3RD ALL INDIA MEDIA EDUCATORS' CONFERENCE-2018 ON POWER OF MEDIA AND TECHNOLOGY: SHAPING THE FUTURE July 6 - 8, 2018 Geeta Girdhar Sabhagaar Pearl Academy of Fashion Designing & Media Jaipur Jointly Organised By: Centre for Mass Communication, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Department of Communication & Journalism, Gauhati University, Guwahati Lok Samvad Sansthan, Jaipur Submitted By: Kalyan Singh Kothari Secretary Lok Samvad Sansthan BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT During the last 70 years since Independence, the position of media has taken a radical shift in India. The ingrained transformation of the Indian society during its journey in the last seven decades, especially in the post-globalization period, has left a noteworthy impact on media. The evolution has also placed challenges before the Indian media scenario. The character of these challenges has kept on changing with the emergence of new social, cultural and political context and has assumed a new perspective following the advent of information technology, Internet and social media, visible in the multiplicity of platforms. The Indian media had a sound role in the struggle for Independence. But it faces a challenge in the present scenario to maintain its high standards commensurate with its glorious past. Subsequently, the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has been entering into all forms of media. Though the entertainment media industry has been the prime area of FDI, the other genres like print, electronic even radio industries are now becoming lucrative targets of FDI. Though a focus is laid on the expansion of facilities or creation of new geographic market to speak high about FDI in media sector, experience and apprehensions point to several negative aspects.