“My Whole Life I've Been Dressing up Like a Man”: Negotiations of Queer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock

Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Home (/gendersarchive1998-2013/) Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock May 1, 2012 • By Linda Mizejewski (/gendersarchive1998-2013/linda-mizejewski) [1] The title of Tina Fey's humorous 2011 memoir, Bossypants, suggests how closely Fey is identified with her Emmy-award winning NBC sitcom 30 Rock (2006-), where she is the "boss"—the show's creator, star, head writer, and executive producer. Fey's reputation as a feminist—indeed, as Hollywood's Token Feminist, as some journalists have wryly pointed out—heavily inflects the character she plays, the "bossy" Liz Lemon, whose idealistic feminism is a mainstay of her characterization and of the show's comedy. Fey's comedy has always focused on gender, beginning with her work on Saturday Night Live (SNL) where she became that show's first female head writer in 1999. A year later she moved from behind the scenes to appear in the "Weekend Update" sketches, attracting national attention as a gifted comic with a penchant for zeroing in on women's issues. Fey's connection to feminist politics escalated when she returned to SNL for guest appearances during the presidential campaign of 2008, first in a sketch protesting the sexist media treatment of Hillary Clinton, and more forcefully, in her stunning imitations of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, which launched Fey into national politics and prominence. [2] On 30 Rock, Liz Lemon is the head writer of an NBC comedy much likeSNL, and she is identified as a "third wave feminist" on the pilot episode. -

Mary, Roseanne, and Carrie: Television and Fictional Feminism by Rachael Horowitz Television, As a Cultural Expression, Is Uniqu

Mary, Roseanne, and Carrie: Television and Fictional Feminism By Rachael Horowitz Television, as a cultural expression, is unique in that it enjoys relatively few boundaries in terms of who receives its messages. Few other art forms share television's ability to cross racial, class and cultural divisions. As an expression of social interactions and social change, social norms and social deviations, television's widespread impact on the true “general public” is unparalleled. For these reasons, the cultural power of television is undeniable. It stands as one of the few unifying experiences for Americans. John Fiske's Media Matters discusses the role of race and gender in US politics, and more specifically, how these issues are informed by the media. He writes, “Television often acts like a relay station: it rarely originates topics of public interest (though it may repress them); rather, what it does is give them high visibility, energize them, and direct or redirect their general orientation before relaying them out again into public circulation.” 1 This process occurred with the topic of feminism, and is exemplified by the most iconic females of recent television history. TV women inevitably represent a strain of diluted feminism. As with any serious subject matter packaged for mass consumption, certain shortcuts emerge that diminish and simplify the original message. In turn, what viewers do see is that much more significant. What the TV writers choose to show people undoubtedly has a significant impact on the understanding of American female identity. In Where the Girls Are , Susan Douglas emphasizes the effect popular culture has on American girls. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

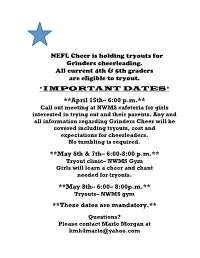

NEFL Grinders Cheer

NEFL Cheer is holding tryouts for Grinders cheerleading. All current 4th & 5th graders are eligible to tryout. *IMPORTANT DATES* **April 15th– 6:00 p.m.** Call out meeting at NWMS cafeteria for girls interested in trying out and their parents. Any and all information regarding Grinders Cheer will be covered including tryouts, cost and expectations for cheerleaders. No tumbling is required. **May 6th & 7th– 6:00-8:00 p.m.** Tryout clinic– NWMS Gym Girls will learn a cheer and chant needed for tryouts. **May 8th– 6:00– 8:00p.m.** Tryouts– NWMS gym **These dates are mandatory.** Questions? Please contact Marlo Morgan at [email protected] NEFL Grinders Cheer The tryouts for NEFL Grinders cheer will be held May 5th-7th from 6:00-8:00 in the upper gym at NWMS. The girls need to wear a t-shirt/tank, shorts, tennis shoes and have their hair pulled back. They should bring a water bottle with them. The first two nights will be the clinic where the girls will learn the cheer and chant needed for the tryouts. The third night will be the tryouts. Parents are welcome to stay in the gym and watch the clinic, but the tryouts are closed. The team will be announced that night after tryouts. All girls must be registered with NEFL before they will be allowed to tryout. You can register online at www.nefl.net. Please bring your printed receipt of registration on the first day of cheer clinic. ************************************************************************ The girls will be judged on a 1-5 scale on the following skills: -Cheer and chant memory -Motions -Voice projection -Enthusiasm -Jumps -Attitude -Tumbling will be scored as follows: -Cartwheel -1 point -Round Off - 2 points -Back Handspring - 3 points -Back Handspring series - 4 points -Tuck – 5 points The cost for participating in Grinders cheer is approximately $325-$350. -

"The Untitled Lena Dunham Project" Pilot (Together)

"THE UNTITLED LENA DUNHAM PROJECT" PILOT (TOGETHER) Written by Lena Dunham 10/23/2010 INT. MIDTOWN RESTAURANT, EVENING HANNAH-- 24, sweet-faced, slightly chubby-- sits across from her parents: TAD--early 60s, professorial-- and LOREEN, slim and understated, also in her 60s. Loreen and Tad slowly work on their food while Hannah eats speedily, back and forth between a bowl of pasta, a salad, a side of spinach and a baked potato. LOREEN Would you two slow down? You’re eating like it’s going out of style. HANNAH (mouth full) I’m a growing girl. A drip of sauce hits Tad’s shirt. TAD Meant to do that. Hannah laughs. LOREEN Your whole Brooklyn thing, Hannah. It reminds me of Berkeley in the 1970s. My boyfriend at the time, Ned. He lived in a communal space a bit like yours. HANNAH (laughing) I have one roommate, mom. LOREEN But that boyfriend of hers seems always to be around. TAD We’re sorry we never got to meet this fellow you’re dating. HANNAH Dating is probably a polite word for what we’re doing, but yeah. LOREEN Hannah, that’s your father. Spare him the TMI. (pause) That’s a thing, right? TMI? (MORE) 2. LOREEN (CONT'D) One of my students said it and I thought it was just so funny. HANNAH (to Tad) I’m sorry, papa. Did that upset you? TAD I’m rolling with it. Pause LOREEN Tad. We should probably bring it up now. TAD Let’s finish recapping the weekend and then we can-- LOREEN No, I don’t want to just leave it til the end of dinner. -

The Queer" Third Species": Tragicomedy in Contemporary

The Queer “Third Species”: Tragicomedy in Contemporary LGBTQ American Literature and Television A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences by Lindsey Kurz, B.A., M.A. March 2018 Committee Chair: Dr. Beth Ash Committee Members: Dr. Lisa Hogeland, Dr. Deborah Meem Abstract This dissertation focuses on the recent popularity of the tragicomedy as a genre for representing queer lives in late-twentieth and twenty-first century America. I argue that the tragicomedy allows for a nuanced portrayal of queer identity because it recognizes the systemic and personal “tragedies” faced by LGBTQ people (discrimination, inadequate legal protection, familial exile, the AIDS epidemic, et cetera), but also acknowledges that even in struggle, in real life and in art, there is humor and comedy. I contend that the contemporary tragicomedy works to depart from the dominant late-nineteenth and twentieth-century trope of queer people as either tragic figures (sick, suicidal, self-loathing) or comedic relief characters by showing complex characters that experience both tragedy and comedy and are themselves both serious and humorous. Building off Verna A. Foster’s 2004 book The Name and Nature of Tragicomedy, I argue that contemporary examples of the tragicomedy share generic characteristics with tragicomedies from previous eras (most notably the Renaissance and modern period), but have also evolved in important ways to work for queer authors. The contemporary tragicomedy, as used by queer authors, mixes comedy and tragedy throughout the text but ultimately ends in “comedy” (meaning the characters survive the tragedies in the text and are optimistic for the future). -

Juniors to Have Prom Girls Glee Club Pre~Ents Nnua Aster Oncert

,. SERlES V VOL. VII Stevens Point, \Vis., April 10, 1946 No. 23 College Band Again Juniors To Have Prom Girls Glee Club Pre~ents To Welcome Alums Of interest to all students is the fact that the first post-war Juni or A 1 E c The col lege band, under Ihe di rec· Promenade will be he!J as originally nnua aster oncert tion of Peter J. Michelsen, wi ll hold sc heduled on Friday, May 24. There · a h omecoming on Saturday and Sun had previously been some question day, April 27 and 28. as to whether it could be held be Holds Initiation Michelsen to Direct Approximately 36 band directors cause of the fact that the date chose n Second semester pledges became The Girls Glee club, under the plan to attend the homecoming. for the Prom was the same as that members of Sigma Tau Delta, na directi on of Peter J. Michelsen, will They wi ll play with the college selected by the freshmen for their tional honora ry English fraternity, present their fifth annual Easte r band, making a total of '65 people in proposed party. After a discussion at a meeting held last Wednesday concert on P,tlm Sunda)', April 14, the organization. between the heads of the two classes, the decision was reached to evening in Studio A. in th; coll ege aud itorium .It 3 o'clock ! he g roup will spend Saturday combine the two events in to the The new members, Joyce Kopitz in the .1fternoon. rehearsing, and on Saturday evening, Junior Prom. -

Click Here to Download The

$10 OFF $10 OFF WELLNESS MEMBERSHIP MICROCHIP New Clients Only All locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Expires 3/31/2020 Expires 3/31/2020 Free First Office Exams FREE EXAM Extended Hours Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Multiple Locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. 4 x 2” ad www.forevervets.com Expires 3/31/2020 Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! June 25 - July 1, 2020 has a new home at INSIDE: THE LINKS! Sports listings, 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 sports quizzes Jacksonville Beach and more Pages 18-19 Offering: · Hydrafacials · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring · B12 Complex / Lipolean Injections ‘Hamilton’ – Disney+ streams Broadway hit Get Skinny with it! “Hamilton” begins streaming Friday on Disney+. (904) 999-0977 1 x 5” ad www.SkinnyJax.com Kathleen Floryan PONTE VEDRA IS A HOT MARKET! REALTOR® Broker Associate BUYER CLOSED THIS IN 5 DAYS! 315 Park Forest Dr. Ponte Vedra, Fl 32081 Price $720,000 Beds 4/Bath 3 Built 2020 Sq Ft. 3,291 904-687-5146 [email protected] Call me to help www.kathleenfloryan.com you buy or sell. 4 x 3” ad BY GEORGE DICKIE Disney+ brings a Broadway smash to What’s Available NOW On streaming with the T American television has a proud mistreated peasant who finds her tradition of bringing award- prince, though she admitted later to winning stage productions to the nerves playing opposite decorated small screen. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Psycho Killers, Circus Freaks, Ordinary People: a Brief History of the Representation of Transgender Identities on American TV Series

Psycho Killers, Circus Freaks, Ordinary People: A Brief History of the Representation of Transgender Identities on American TV Series Abstract: In 1965, popular TV Series The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (NBC) aired the episode “An Unlocked Window”, in which it is revealed that the nurses killer in the area is a transvestite. It was the first time a transgender character appeared on a TV series, and until the late 80s that was the most stereotypical and basic – because it was minimal – representation of transsexuals on broadcast TV series and films: as psychopaths and serial killers. Other examples are Aldo Lado’s Who Saw Her Die? (1972), Brian de Palma’s Dressed to Killed (1980), Robert Hiltzick’s Sleepaway Camp (1983) and Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1991). Throughout the 90s the paradigm changed completely and transsexual characters became much more frequent. However, the change was not for good, as they were turned now into objects of mockery and disgust in comedy TV series and films, in which the protagonist heterosexual male was “deceived” into kissing or having sex with an “abhorrent” trans just as a comic device. In the comedies Soapdish (1991), Ace Ventura (1994), and Naked Gun 33 1/3 (1994), the male protagonist ends up literally throwing up when he realizes that the girl he had been kissing was not born a female. Friends (1994-2004) and Ally McBeal (1997-2002) are also series of the late 90s in which the way transgender characters are represented is far from being appropriate. It has not been until the Golden Globe and Emmy awarded TV series Transparent (2014-2016) when transgender issues have been put realistically on the front line with the accuracy and integrity that they deserve. -

Daisy 5 Flowers, 4 Stories, 3 Cheers for Animals! Activity

Daisy 5 Flowers, 4 Stories, 3 Cheers for Animals! Activity Plan 1: Birdbath Award Purpose: When girls have earned this award, they will be able to say “Animals need care; I need care. I can do both.” Planning Guides Link: Leadership Activity Plan Length: 1.5 hours Resources and Tips • This activity plan has been adapted from It’s Your Story—Tell It! 5 Flowers, 4 Stories, 3 Cheers for Animals!, which can be used for additional information and activities. • Important snack note: Please check with parents and girls to see if they have any food allergies. The snack activity calls for peanut butter or a dairy product. Ask parents for alternative options that will work for the activity, if needed. Activity #1: Unique Animals Journey Connection: Session 4—Fantastical Animals Flip Book Time Allotment: 15 minutes Materials Needed: • Note cards • Coloring utensils • Tape • Paper Steps: 1. Create a list of animal body parts (head, arm, leg, ears, tail, etc.) on individual small pieces of paper. 2. Ask the girls the questions below: • What animals have you seen near where you live? • What is the most unusual animal you’ve ever seen? Where did you see it? What did it look like? 3. Split the girls into teams, hand out note cards and assign 1–2 animal body parts per girl (depending on the number of girls per group). Instruct girls not to talk to each other and to draw the body part they have on the note card for an animal, real or imaginary. 4. After girls have finished their drawings, have them work as a team to tape the different animal body parts together to create a totally unique animal friend. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................