Queer, Or Cross-Dressers (China Development Brief 2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2019 Edition

Volume XXXVII No. 7 August 2019 Montreal, QC www.filipinostar.org Manuel re-elected FAMAS president See page 4 report by Willie Quiambao Cesar Manuel (6th from the left, flanked by Councilors Marvin Rotrand and Lionel Perez) and his party, Samahang Makabayan, won a landslide victory during the FAMAS elections held on August 4, 2019 at the community center on Van Horne Avenue. Photo taken during the appreciation and victory party held on August 18, 2019. (Photo from Marvin Rotrand’s facebook) G7 Highlights on Final Day of Meetings: Iran, Climate Change and China Trade President Trump spoke again get Tehran through its current financial about the trade war, President difficulties if talks open. Emmanuel Macron of France Mr. Trump was responding to discussed diplomacy with Iran, an overture by President Emmanuel and world leaders agreed on Macron of France, who said that he Amazon aid. would try to set up such a meeting in August 26, 2019 [T he final day the next few weeks, to seek a of the Group of 7 meeting in France resolution of decades of conflict ended in whiplash for global leaders between Iran and the United States. and swerves toward diplomacy with Mr. Macron, who said he had China and Iran for President Trump.] spoken with Mr. Rouhani, said that if President Trump said on the American and Iranian presidents Monday that he would be open to met, “my conviction was that an meeting with President Hassan agreement can be met,” addressing Rouhani of Iran, and would even be President Trump and President Macron of France during their willing to support short-term loans to See Page 4 G7 Highlights final press conference of the Group of 7 summit in Biarritz, France, on Monday.CreditErin Schaff/The New York Times 2 August 2019 The North American Filipino Star change. -

Online Questionnaires

Online Questionnaires Re-thinking Transgenderism The Trans Research Review • Understanding online trans communities. • Comprehending present-day transvestism. • Inconsistent definitions of ‘transgenderism’ and the connected terms. • !Information regarding • Transphobia. • Family matters with trans people. • Employment issues concerning trans people. • Presentations of trans people within media. The Questionnaires • ‘Male-To-Female’ (‘MTF’) transsexual people [84 questions] ! • ‘MTF’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists [83 questions] ! • ‘Significant Others’ (Partners of trans people) [49 questions] ! • ‘Female To Male’ (‘FTM’) transsexual people [80 questions] ! • ‘FTM’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists [75 questions] ! • ‘Trans Admirers’ (Individuals attracted to trans people) • [50 questions] The Questionnaires 2nd Jan. 2007 to ~ 12th Dec. 2010 on the international Gender Society website and gained 390,227 inputs worldwide ‘Male-To-Female’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: Being 'In the closet' - transgendered only in private or Being 'Out of the closet' - transgendered in (some) public places 204 ‘Female-To-Male’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: Being 'In the closet' - transgendered only in private or Being 'Out of the closet' - transgendered in (some) public places 0.58 1 - Understanding online trans communities. Transgender Support/Help Websites ‘Male-To-Female’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: (679 responses) Always 41 Often 206 Sometimes 365 Never 67 0 100 200 300 400 1 - Understanding -

NOSI BALASI? MNLF Lay Siege on Zamboanga City

September 2013 1 JOIN OUR GROWING NUMBER OF INTERNET READERS RECEIVE A FREE MONTHLY ONLINE SEPTEMBER 2013 COPY. Vol. 2 No.9 EMAIL US AT: wavesnews247 @gmail.com Double Trouble PNoy faces two big crisis: Pork Barrel “Scam-dal” MNLF Zambo attack NOSI BALASI? MNLF Lay Siege on Zamboanga City By wavesnews staff with files from Philippine Daily Inquirer By wavesnews staff with files from Philippine Daily Inquirer NOSI BALASI ? SINO BA SILA ? Who are the senators, congressmen, govern- ment officials and other individuals involved in the yet biggest corruption case ever to hit the Philippine government to the tune of billions and bil- lions of pesos as probers continue to unearth more anomalies on the pork barrel or Priority Development Assistance fund (PDAF)? Sept.16, Monday, the department of Justice formally filed plunder charges against senators Ramon “Bong Revilla jr., Jinggoy Estrada and Juan Ponce Combat police forces check their comrade (C) who was hit by Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) sniper fire in downtown Zamboanga City. Photo: AFP CHARGED! Muslim rebels under the Moro Na- standstill, classes suspended and tional Liberation Front (MNLF) of curfew enforced from 8:00pm to Nur Misuari “invaded” Zamboanga 5:00am to protect residents being city Sept.8 at dawn taking over sev- caught in the hostilities. eral barangays (villages), held hun- dreds of residents hostages and Already there are some 82,000 dis- (from left) Senate Minority Leader Juan Ponce-Enrile, and Senators Jose “Jinggoy” Es- placed residents of the city while at trada and Ramon “Bong” Revilla Jr. INQUIRER FILE PHOTOS engaged government soldiers in running gun battles that has so far least four barangays remained un- Enrile along with alleged mastermind Janet Lim Napoles and 37 others. -

Fantasy Land Rebel Reformer

Msgr. Gutierrez Spiritual: A Beginning or an End? – p. 10 Zena Babao Lifestyle: The Dance of Marriage – p. 9 Miles Beauchamp Perspectives: Changing Sounds – p. 6 Entertainment Lani Misalucha and guest coming to Pechanga – p. 16 March 20-26, 2015 The original and first Asian Journal in America San Diego’s rst and only Asian Filipino weekly publication and a multi-award winning newspaper! Online+Digital+Print Editions to best serve you! 550 E. 8th St., Ste. 6, National City, San Diego County, CA USA 91950 | Ph 619.474.0588 | [email protected] | Follow us on Twitter @asianjournal | www.asianjournalusa.com 44% of Pinoys oppose passage of BBL —Pulse Asia GMA Network | MANILA, 3/19/2015 — Nearly half of Philippine start-up gets funding Filipinos oppose the passage Fantasy Land of the draft Bangsamoro Basic from Silicon Valley Law, a Pulse Asia poll re- ABS CBN News | MA- Gordon. vealed Thursday. NILA, 3/18/2015- A Philip- The tech start-up gener- Rebel Reformer Based on a survey conduct- pine tech start-up aiming to ated $2 million, said to be the By Simeon G. Silverio, Jr. ed on 1,200 Filipino adults revolutionize job search has largest fund raised by a local Chapter 17 of the book, “Fantasy Land” By Simeon G. Silverio, Jr., Publisher & Editor, earlier this month, 44 percent raised additional funding from start-up so far. Several inves- Asian Journal San Diego, the Original and First Asian Journal in America of the respondents disagreed Silicon Valley investors. tors made this possible, 75% when asked if the BBL should Kalibrr joins other success- of which are foreign-based be passed. -

Hospitalization Will Be Free for Poor Filipinos

2017 JANUARY HAPPY NEW YEAR 2017 Hospitalization will be Pacquiao help Cambodia free for poor Filipinos manage traffic STORY INSIDE PHNOM PENH – Philippine boxing icon Sena- tor Manny Pacquiao has been tapped to help the Cambodian government in raising public aware- ness on traffic management and safety. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen made the “personal request” to Pacquiao in the ASEAN country’s bid to reduce road traffic injuries in the country. MARCOS continued on page 7 WHY JANUARY IS THE MONTH FOR SINGLES STORY INSIDE Who’s The Dancer In The House Now? Hannah Alilio performs at the Christmas Dr. Solon Guzman seems to be trying to teach his daughters Princess and Angelina new moves at Ayesha de Guzman and Kayla Vitasa enjoy a night out at the party of Forex Cargo. the Dundas Tower Dental and Milton Dental Annual Philippine Canadian Charitable Foundation / AFCM / OLA Christmas party. Christmas Party. Lovebirds Charms Friends Forex and THD man Ted Dayno is all smiles at the Forex Christmas dinner with his lovely wife Rhodora. Star Entertainment Circle’s Charms relaxes prior to the start of the Journalist Jojo Taduran poses with Irene Reeder, wife Star Circle Christmas Variety Show. of former Canada Ambassador to the Phl Neil Reeder. JANUARY 2017 JANUARY 2017 1 2 JANUARY 2017 JANUARY 2017 Paolo Contis to LJ Reyes: “I promise to protect your Honey Shot heart so it will never get hurt ever again” Paolo Contis shares the sweetest message to LJ Reyes for her birthday on December 25. Alden and Maine in In his Insta- gram account a TV series, finally the actor poured his heart out Every popular love team has their own as he shared a TVCs (a lot of them), big screen projects collage of LJ’s and a television series. -

View Full Issue As

IN Step • LGBT Wisconsin's Community Newspaper • Founded in 1984 Nov. t8 - Dec. 1, 1999 • Vol. XVI, Issue XXIII• $2.95 outside of Wisconsin SECTION ONE: NEWS: 'Creating Change' Hits Hot Topics McCain Woos Gay Republicans • Gay.com Sets Record NEWS FEATURE: Wisconsin LGBT Groups Foil Anti-Gay Billboards Quips and Quotes • Letters • Paul Berke Cartoon • Casual Observer SECTION Q: INTERVIEW: COMEDY DIVA MARGARET CHO MUSIC: linda Rondstadt and More FREEPersonals • The (lassies • The Calendar • Keepin' IN Step with Jamie • The Guide k 1\sv Helms Boots Baldwin, Other on religion echoed Travers' position, insisting that they may fear Falwell and Congresswomen, Creating Change Hits Hot Topics other far-right fundamentalist leaders and may be angered by their actions, but from Hearings million war chest they expect an all-out that they don't hate them. Washington — Among the io Anti-Marriage media campaign after the December hol- Some pointed out that at least 20 U.S. House of Representatives idays. "There is going to be an intense gays and lesbians had been murdered in members ordered expelled from a Initiative & `Stop radio and TV campaign for this initia- the past year with hundreds of other anti- Senate Foreign Relations Commit- Hating' Religious tive," openly gay San Francisco Supervi- gay attacks taking place around the coun- tee hearing by its chairman, Sen. sor Mark Leno told the conference. "It's try. "I'd have a difficult time pointing to Right on Agenda not going to be pleasant." one actual case of a killing or even an Although California's looming ballot attack aimed at a fundamentalist Christ- by Keith Clark measure got most of the attention at the ian in this country because of their reli- conference, the most controversial issue activist in the audi- of the IN Step staff gious beliefs," one arose from a panel on religion at which ence said. -

19 December 1994

* TODAY: RUSSIA BOMBS ·CHECHEN * MAKWETU HANGS ONTO' PAC LEADERSHIP * LATEST BONDS * > Bringing Africa South Vol No 564 N$1 .50 (GST ,Inc.) Tuesday December 20 1994 Plane crashes near Sesfontein • LU CIENNE FI LD THE two crew members of a small Cana 'd .··N<lItUlI" _C'':'''Q fN<lItlYnhl <llt n '· W .... .,.. ..n '. ..... ~""l • .rI .._ht ···· dian aircraft which crashed in north-east ~~~:~!~i~~~£~~~Opuwo. ;?ii:~~:~~~~~~~B oth crew mem bers ~~:~~;.~;~~~:~::th at th e pI ane dI not !lll;lllll i ern Namibia while conducting a geological Grellmann said ·two were found dead. Their belong to Westair survey on Sunday are dead. planes and one helicop- bodies will be flown to Aviation and that A Westair Aviation ling at Sesfontein on ter left Windhoek early Windhoek before being maintenance on the spokesperson, Karin Sunday as scheduled, yesterday morning to flown home to Canada. plane was done using Grellmann, said the The Canadian plane search for the plane and It is thought that the Westair facilities. As plane, a Cessna 402 with two Canadian crew crew members after no planemusthavecrashed a result the company Titan, was reported members on board had news was received, into a mountain and had been asked tohelp missing after it failed bee~ conducting,a geo- Yesterdaythe,charred burst into, flames. w~e~ the plane went ;:,-:; Tb~fe. ,. are . clirrently . l :.· 9.:57 . ~~d~ntsJ~)1ng : Jlf t to turn up for refuel- logIcal survey m Na- wreck of the Il l-fated Grellmann SaId only the mlss1Og. t,h~ . ~OtP,9~ ,'Pe.r c~Dt .gf, ,\!~QQ(~r~ · fJ;Qm A~g~J~. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

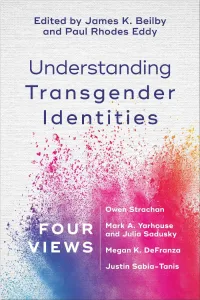

Understanding Transgender Identities

Understanding Transgender Identities FOUR VIEWS Edited by James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy K James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy, Understanding Transgender Identities Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2019. Used by permission. _Beilby_UnderstandingTransgender_BB_bb.indd 3 9/11/19 8:21 AM Contents Acknowledgments ix Understanding Transgender Experiences and Identities: An Introduction Paul Rhodes Eddy and James K. Beilby 1 Transgender Experiences and Identities: A History 3 Transgender Experiences and Identities Today: Some Issues and Controversies 13 Transgender Experiences and Identities in Christian Perspective 44 Introducing Our Conversation 53 1. Transition or Transformation? A Moral- Theological Exploration of Christianity and Gender Dysphoria Owen Strachan 55 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 84 Response by Megan K. DeFranza 90 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 95 2. The Complexities of Gender Identity: Toward a More Nuanced Response to the Transgender Experience Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 101 Response by Owen Strachan 131 Response by Megan K. DeFranza 136 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 142 3. Good News for Gender Minorities Megan K. DeFranza 147 Response by Owen Strachan 179 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 184 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 190 vii James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy, Understanding Transgender Identities Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2019. Used by permission. _Beilby_UnderstandingTransgender_BB_bb.indd 7 9/11/19 8:21 AM viii Contents 4. Holy Creation, Wholly Creative: God’s Intention for Gender Diversity Justin Sabia- Tanis 195 Response by Owen Strachan 223 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 228 Response by Megan K. -

Namibia A-Ccused of 'Cultural

,':."'," . .'. '· ~- 'TODI\Y: tllTIMATVM{FORANGOl:ANS :tr·OAU TO SHUT NAM OFFlce',* SPORT: * I I I t ' I ,If f Bringing Africa South I I .Namibia a-ccused of 'cultural genocide' I A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS ... and eyes that say it all:This youngster was among those, individuals and businesses, who yesterday turned out to meet Miss Universe, f Michelle McLean (left).in central Windhoek, and contribute to the Michelle McLean Strange alliance takes Trust Fund for children. McLean has put some of her.prize money into the fund. In ~ I her response to the final key' question of the Miss Vniverse contest, McLean put children first in development priorities. Photograph: CODrad Ailgula iI its ,case to b d·ies . - bers on the board are given McLean salutes children' STAFF REPORTER as 'Colonel Oesmond JW NAMIBIA has been 'reported' to the United Nations Radmore, Jacobus J Brand, Human Rights C9mmission and Unesco over its move to Cultura chair, and Manuel CD Oliviera Coelho, direc as the nation's future expropriate the assets of Cultura 2000, and the alleged tor; while other N amibians ''vi~lation of cultural and minority rights in post-apart- heid Namibia". listed are Kaptein Hans MICHELLE McLean yes- said they had made her short Diergaardt, Kaptein, Bas terday paid tribute to the MAGRETH NUNUHE stay in Nainibia "reallyspe- Seemingly prompted by mainly to be drawn from ters; Joel Gebhanlt, Owambo fears that the "West Euro conservative, if not right children she swore to pro- cial". leader; and Riaan Ooete, teet in response to the ft- year-old McLean-' as the ' , "I've never felt so loved. -

Cinemagis 9: Northern Mindanao's Sentiments and Sensitivities

In partnership with Cinemagis 9: Northern Mindanao’s sentiments and sensitivities By Stephen J Pedroza s a springboard for budding and from the personal to a more collective of our voices and aspirations shared established artists to tackle a wide experience where social issues could and celebrated beyond any competition The films ... Arange of social issues in Mindanao either be clearly seen or implied to there is — I would like to emphasize using film as the medium, Cinemagis has magnify tension and to 'problematize' that Cinemagis’s prime role, apart from ‘problematize’ curated motion pictures that have already the mundane and dissect it as giving away awards, is to celebrate the the mundane been screened and awarded in national and determination, pursuit, identification, harvest, the good harvest, the good international independent film festivals. emancipation, tradition, poverty, life, ones. We may not have the school for and dissect it as Now on its ninth installment, love, and death,” he adds. filmmaking yet, but I hope we have the Cinemagis continues to serve as a platform Over the years, Cinemagis has grown humility and high respect for the craft determination, for young and professional filmmakers prolifically and Savior, who helms Xavier beyond any other reasons there are. pursuit, in Northern Mindanao to pour out their University - Ateneo de Cagayan's Xavier Northern Mindanao filmmakers create passion, stories, and filmmaking skills, and Center for Culture and the Arts (XCCA) these films because there is so much to identification, for cultivating the experience and growth as director, attributes this momentum show and share!” says the XCCA director. -

Art Archive 02 Contents

ART ARCHIVE 02 CONTENTS The Japan Foundation, Manila A NEW AGE OF CONTEMPORARY PHILIPPINE CINEMA AND LITERATURE ART ARCHIVE 02 by Patricia Tumang The Golden Ages THE HISTORIC AND THE EPIC: PHILIPPINE COMICS: Contemporary Fiction from Mindanao Tradition and Innovation by John Bengan Retracing Movement Redefiningby Roy Agustin Contemporary WHAT WE DON’T KNOW HistoriesABOUT THE BOOKS WE KNOW & Performativity Visual Art by Patricia May B. Jurilla, PhD SILLIMAN AND BEYOND: FESTIVALS AND THE LITERARY IMAGINATIONS A Look Inside the Writers’ Workshop by Andrea Pasion-Flores by Tara FT Sering NEW PERSPECTIVES: Philippine Cinema at the Crossroads by Nick Deocampo Third Waves CURRENT FILM DISTRIBUTION TRENDS IN THE PHILIPPINES by Baby Ruth Villarama DIGITAL DOCUMENTARY TRADITIONS Regional to National by Adjani Arumpac SMALL FILM, GLOBAL CONNECTIONS Contributor Biographies by Patrick F. Campos A THIRD WAVE: Potential Future for Alternative Cinema by Dodo Dayao CREATING RIPPLES IN PHILIPPINE CINEMA: Directory of Philippine The Rise of Regional Cinema by Katrina Ross Tan Film and Literature Institutions ABOUT ART ARCHIVE 02 The Japan Foundation is Japan’s only institution dedicated to carrying out comprehensive international cultural exchange programs throughout the world. With the objective of cultivating friendship and ties between Japan and the world through culture, language, and dialogue, the Japan Foundation creates global opportunities to foster trust and mutual understanding. As the 18th overseas office, The Japan Foundation, Manila was founded in 1996, active in three focused areas: Arts and Culture; Japanese Studies and Intellectual Exchange; Japanese- Language Education. This book is the second volume of the ART ARCHIVE series, which explores the current trends and concerns in Philippine contemporary art, published also in digital format for accessibility and distribution on a global scale.