University of the Witwatersrand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

Negotiating Meaning and Change in Space and Material Culture: An

NEGOTIATING MEANING AND CHANGE IN SPACE AND MATERIAL CULTURE An ethno-archaeological study among semi-nomadic Himba and Herera herders in north-western Namibia By Margaret Jacobsohn Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town July 1995 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. Figure 1.1. An increasingly common sight in Opuwo, Kunene region. A well known postcard by Namibian photographer TONY PUPKEWITZ ,--------------------------------------·---·------------~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ideas in this thesis originated in numerous stimulating discussions in the 1980s with colleagues in and out of my field: In particular, I thank my supervisor, Andrew B. Smith, Martin Hall, John Parkington, Royden Yates, Lita Webley, Yvonne Brink and Megan Biesele. Many people helped me in various ways during my years of being a nomad in Namibia: These include Molly Green of Cape Town, Rod and Val Lichtman and the Le Roux family of Windhoek. Special thanks are due to my two translators, Shorty Kasaona, and the late Kaupiti Tjipomba, and to Garth Owen-Smith, who shared with me the good and the bad, as well as his deep knowledge of Kunene and its people. Without these three Namibians, there would be no thesis. Field assistance was given by Tina Coombes and Denny Smith. -

Randi-Markusen-Botsw

The Baherero of Botswana and a Legacy of Genocide Randi Markusen Member, Board of Directors World Without Genocide The Republic of Botswana is an African success story. It emerged in 1966 as a stable, multi-ethnic, democracy after eighty-one years as Bechuanaland, a British Protectorate. It was a model for progress, unlike many of its neighbors. Scholars from around the globe were eager to study and chronicle its people and formation. They hoped to learn what made it the exception, and so different from the rest of the continent.1 Investigations most often focused on two groups, the San, who were indigenous hunter-gathers, and the Tswana, the country’s largest ethnic group. But the scholars neglected other groups in their research. The Herero, who came to Botswana from Namibia in the early 1900s, long before independence, found themselves in that neglected category and were often unmentioned, even though their contributions were rich and their experiences compelling.2 The key to understanding the Herero in Botswana today lies in their past. A Short History of the Herero People The Herero have lived in the Southwest region of Africa for hundreds of years. They are believed to be descendants of pastoral migrants from Central Africa who made their way southwest during the 17th century and eventually inhabited what is now northern Namibia. In the middle of the 19th century they expanded farther south, seeking additional grassland for their cattle. This encroachment created conflicts with earlier migrants and indigenous groups. As a result, the Herero were engaged in on-and- off inter-tribal wars. -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

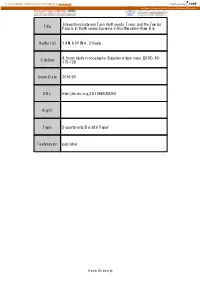

Interactions Between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Interactions between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia Author(s) YAMASHINA, Chisato African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2010), 40: Citation 115-128 Issue Date 2010-03 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/96293 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl.40: 115-128, March 2010 115 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TERMITE MOUNDS, TREES, AND THE ZEMBA PEOPLE IN THE MOPANE SAVANNA IN NORTH- WESTERN NAMIBIA Chisato YAMASHINA Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Termite mounds comprise a significant part of the landscape in northwestern Namibia. The vegetation type in this area is mopane vegetation, a vegetation type unique to southern Africa. In the area where I conducted research, almost all termite mounds coex- isted with trees, of which 80% were mopane. The rate at which trees withered was higher on the termite mounds than outside them, and few saplings, seedlings, or grasses grew on the mounds, indicating that termite mounds could cause trees to wither and suppress the growth of plants. However, even though termite mounds appeared to have a negative impact on veg- etation, they could actually have positive effects on the growth of mopane vegetation. More- over, local people use the soil of termite mounds as construction material, and this utilization may have an effect on vegetation change if they are removing the mounds that are inhospita- ble for the growth of plants. -

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society Michael Bollig and Jan-Bart Gewald Everybody living in Namibia, travelling to the country or working in it has an idea as to who the Herero are. In Germany, where most of this book has been compiled and edited, the Herero have entered the public lore of German colonialism alongside the East African askari of German imperial songs. However, what is remembered about the Herero is the alleged racial pride and conservatism of the Herero, cherished in the mythico-histories of the German colonial experiment, but not the atrocities committed by German forces against Herero in a vicious genocidal war. Notions of Herero, their tradition and their identity abound. These are solid and ostensibly more homogeneous than visions of other groups. No travel guide without photographs of Herero women displaying their out-of-time victorian dresses and Herero men wearing highly decorated uniforms and proudly riding their horses at parades. These images leave little doubt that Herero identity can be captured in photography, in contrast to other population groups in Namibia. Without a doubt, the sight of massed ranks of marching Herero men and women dressed in scarlet and khaki, make for excellent photographic opportunities. Indeed, the populär image of the Herero at present appears to depend entirely upon these impressive displays. Yet obviously there is more to the Herero than mere picture post-cards. Herero have not been passive targets of colonial and present-day global image- creators. They contributed actively to the formulation of these images and have played on them in order to achieve political aims and create internal conformity and cohesion. -

The Ovaherero/Nama Genocide: a Case for an Apology and Reparations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal June 2017 /SPECIAL/ edition ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 The Ovaherero/Nama Genocide: A Case for an Apology and Reparations Nick Sprenger Robert G. Rodriguez, PhD Texas A&M University-Commerce Ngondi A. Kamaṱuka, PhD University of Kansas Abstract This research examines the consequences of the Ovaherero and Nama massacres occurring in modern Namibia from 1904-08 and perpetuated by Imperial Germany. Recent political advances made by, among other groups, the Association of the Ovaherero Genocide in the United States of America, toward mutual understanding with the Federal Republic of Germany necessitates a comprehensive study about the event itself, its long-term implications, and the more current vocalization toward an apology and reparations for the Ovaherero and Nama peoples. Resulting from the Extermination Orders of 1904 and 1905 as articulated by Kaiser Wilhelm II’s Imperial Germany, over 65,000 Ovaherero and 10,000 Nama peoples perished in what was the first systematic genocide of the twentieth century. This study assesses the historical circumstances surrounding these genocidal policies carried out by Imperial Germany, and seeks to place the devastating loss of life, culture, and property within its proper historical context. The question of restorative justice also receives analysis, as this research evaluates the case made by the Ovaherero and Nama peoples in their petitions for compensation. Beyond the history of the event itself and its long-term effects, the paper adopts a comparative approach by which to integrate the Ovaherero and Nama calls for reparations into an established precedent. -

Hegenberger and Burger Oorlogsende Porphyry

Communs Geol. Surv. SW Africa/Namibia, 1 (1985) 23-30 THE OORLOGSENDE PORPHYRY MEMBER, SOUTH WEST AFRICA/ NAMIBIA: ITS AGE AND REGIONAL SETTING by W. Hegenberger and A.J. Burger ABSTRACT per Sinclair Sequence. Formerly, it was included in the Skumok Formation (Schalk 1961; Geological Map of +18 The age of 1094 -20 m.y. of the Oorlogsende Porphy- South West Africa 1963; Martin 1965), a name that is ry (Area 2120) supports correlation with the Nückopf now obsolete. Formation, an equivalent of the Sinclair Sequence. The rocks form a tectonic sliver, and their position suggests 2. OCCURRENCE AND DESCRIPTION OF THE that the southern Damara thrust belt continues into the ROCKS Epukiro area. Dependent on whether the Kgwebe for- mation in Botswana is considered coeval with either the Several isolated outcrops of feldspar-quartz porphyry Eskadron Formation (Witvlei area, Gobabis District) occur over a distance of 9 km in the Epukiro Omuram- or with the Nückopf Formation of central South West ba and its tributaries in Hereroland East (Area 2120; Africa/Namibia, the correlation of the Ghanzi Group 21°25’S, 20015’E), halfway between the Red Line and in Botswana with only the Nosib Group or with both Oorlogsende (Fig. 2). The nearest site to lend a name the Eskadron Formation and the Nosib Group of South is Oorlogsende, a deserted cattle-post situated about 8 West Africa/Namibia is implied. km to the east of the easternmost porphyry outcrop. No rock type other than the porphyry is exposed. UITTREKSEL The porphyry is a massive, hard, grey to black rhy- olitic rock with a light brownish weathered crust. -

The Politics of Separation: the Case of the Ovaherero of Ngamiland

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies, vol. 13, nos. 1 & 2 (1999) The politics of separation: the case of the OvaHerero of Ngamiland George Uaisana Manase A number of OvaHerero, fleeing the German war of extermination in 1904, crossed from German South West Africa (Namibia) into the Bechuianaland Protectorate and settled in Ngamiland. These OvaHerero came under Tawana overlordship, but retained their cultural identity and even a large degree of their political structures. Initially destitute and unfamiliar with Bechuanaland conditions, they became richer over time. Although proposals for a return to Namibia, including one involved with Tshekedi Khama's campaign against the incorporation of South West Africa into South Africa, were not realized, the desire to return remained. Politically the Ngamiland OvaHerero were associated with SWANU more than SWAPo. In spite of the distance separating the Ovaherero of Ngamiland and those in Namibia,l there has been a continued desire on the side ofthe Ngamiland Ovaherero to go back to Namibia. The strength of this desire has varied through time due to political and economic pull and push forces. From the Namibian side, the fundamental issue has been the political relations between the various Namibian Administrations and the Ovaherero of Namibia. As long as Namibian Hereros remained on bad terms with the various colonial administrations, the Ovaherero of Ngamiland could not be welcomed in the land of their birth. -

Three Essays on Namibian History

Three essays on Namibian history by Neville Alexander The essays in this volume were first published in Namibian Review Publications No. 1, June 1983. © Copyright Neville Alexander All rights reserved. This digital edition published 2013 © Copyright The Estate of Neville Edward Alexander 2013 This edition is not for sale and is available for non-commercial use only. All enquiries relating to commercial use, distribution or storage should be addressed to the publisher: The Estate of Neville Edward Alexander, PO Box 1384, Sea Point 8060, South Africa 1 CONTENTS Preface to the first edition 3 Jakob Marengo and Namibian history 8 Responses to German rule in Namibia or The enigma of the Khowesin 24 The Namibian war of anti-colonial resistance 1904–1907 49 2 PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION THE Namibian Review: A Journal of Contemporary Namibian Affairs has been published since November 1976. Initially it was produced by the Namibian Review Group (known as the Swedish Namibian Association) and 14 editions were printed by the end of 1978. It did not appear in 1979 as in that period we translocated ourselves from Stockholm to Windhoek – i.e. we returned home after 15 years in exile and we wrote directly for a political party, now defunct in all but name. The Namibian Review resumed publication in 1980 and has been appearing ever since with the latest edition devoting its leading article to a survey of Namibia at the beginning of 1983 and the most recent round of talks between the Administrator General and the ‘internal parties’ on (another) possible interim constitution. -

THE Hfzreelo in BOTSWANA by Kirsten Alnaes Preamble The

OR& TRADITION AND IDENTITY: THE HfZREElO IN BOTSWANA by Kirsten Alnaes Preamble The problem of ethnicity, ethnic minorities and ethnic boundaries is a recurrent theme in social anthropology. Much of the discussion about ethnic identity has centred on the cognitive or categorizing aspects, and few have included the affective dimension, although indicating an awareness of it. (1) In fact, the affective dimension seems deliberately not to be included. As Cohen puts it, "In terms of observable and verifiable criteria, what matters sociologically is what people actually do, not what they subjectively think or what they think they think". (2) Epstein, however, suggests an approach in which the affective aspects of ethnic identity are also incorporated. He says: If... the one major conviction that emerged was the powerful emotional charge which seems to underlie so much of ethnic behaviour; and it is this affective dimension of the problem that seems to me lacking in so many recent attempts to tackle it [the problem of ethnicity]." (3) This paper is a preliminary attempt to analyse the perception of history - as it appears in oral tradition - as an expression of ethnic identity. I will argue that oral tradition not only upholds and reinforces ethnic identity, but that it is also an idiom which can be used to voice, and give form to, the emotional aspects of identity. In this paper I am particularly interested in showing why, for the Herero, it seems to be necessary to keep the past alive so as to justify the present. We know that historical documentation is selective and that this applies to written sources as well as oral tradition. -

A Reader in Namibian Politics

State, Society and Democracy A Reader in Namibian Politics Edited by Christiaan Keulder Macmillan Education Namibia Publication of this book was made possible by the generous support of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. The views expressed by the authors are not necessarily the views of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung P.O.Box 1145, Windhoek Namibia Tel: +264 61 225568 Fax: +264 61 225678 www.kas.de/namibia © Konrad Adenauer Stiftung & individual authors, 2010 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. Language editing by Sandie Fitchat Cover image by Melody Futter First published 2000 Reprinted 2010 Macmillan Education Namibia (Pty) Ltd P O Box 22830 Windhoek Namibia ISBN 978 99916 0265 3 Printed by John Meinert Printing, Windhoek, Namibia State, Society and Democracy Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ vii List of Contributors ...................................................................................... viii List of Abbreviations ........................................................................................ix Introduction Christiaan Keulder ..............................................................................................1