Spatial Dynamics of Coastal Forest Bird Assemblages: the Influence of Landscape Context, Forest Type, and Structural Connectivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF). -

Building Nature's Safety Net 2008

Building Nature’s Safety Net 2008 Progress on the Directions for the National Reserve System Paul Sattler and Martin Taylor Telstra is a proud partner of the WWF Building Nature's Map sources and caveats Safety Net initiative. The Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia © WWF-Australia. All rights protected (IBRA) version 6.1 (2004) and the CAPAD (2006) were ISBN: 1 921031 271 developed through cooperative efforts of the Australian Authors: Paul Sattler and Martin Taylor Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage WWF-Australia and the Arts and State/Territory land management agencies. Head Office Custodianship rests with these agencies. GPO Box 528 Maps are copyright © the Australian Government Department Sydney NSW 2001 of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts 2008 or © Tel: +612 9281 5515 Fax: +612 9281 1060 WWF-Australia as indicated. www.wwf.org.au About the Authors First published March 2008 by WWF-Australia. Any reproduction in full or part of this publication must Paul Sattler OAM mention the title and credit the above mentioned publisher Paul has a lifetime experience working professionally in as the copyright owner. The report is may also be nature conservation. In the early 1990’s, whilst with the downloaded as a pdf file from the WWF-Australia website. Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Paul was the principal This report should be cited as: architect in doubling Queensland’s National Park estate. This included the implementation of representative park networks Sattler, P.S. and Taylor, M.F.J. 2008. Building Nature’s for bioregions across the State. Paul initiated and guided the Safety Net 2008. -

Littoral Rainforests and Coastal Vine Thickets of Eastern Australia

Littoral Rainforest and Coastal Vine Thickets of Eastern Australia A nationally threatened ecological community Littoral Rainforest and Coastal Vine Thickets of Eastern Australia 1 POLICY STATEMENT 3.9 Littoral Rainforest and Coastal Vine Thickets of Eastern Australia A nationally threatened ecological community This brochure is designed to assist land managers, owners and occupiers to identify, assess and manage the Littoral Rainforest and Coastal Vine Thickets of Eastern Australia, an ecological community listed under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). The brochure is a companion document for the listing advice which can be found at the Australian Government’s species profile and threats database (SPRAT). Please go to the Littoral Rainforest and Coastal Vine Thickets of Eastern Australia profile in SPRAT: www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publiclookupcommunities.pl 2 Littoral Rainforest and Coastal Vine Thickets of Eastern Australia What is an ecological community? An ecological community is a unique and naturally occurring group of plants and animals. Its presence and distribution is determined by environmental factors such as soil type, position in the landscape, climate and water availability. Species within such communities interact and depend on each other - for example, for food or shelter. Examples of communities listed under the EPBC Act include woodlands, grasslands, shrublands, forests, wetlands, ground springs and cave communities. Together with threatened species, ecological Management Authority Tropics © Wet communities are protected as one of several matters Ptilinopus superbus, superb fruit dove. Listed Marine Species of National Environmental Significance under the EPBC Ecological communities provide a range of ecosystem Act. -

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF). -

Identifying Special Or Unique Sites in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area for Inclusion in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003

Identifying Special or Unique Sites in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area for inclusion in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003 Compiled by Kirstin Dobbs Identifying Special or Unique Sites in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area for inclusion in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003 Compiled by Kirstin Dobbs © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 Published by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority ISBN 978 1 876945 66 4 (pdf) This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without the prior written permission of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry : Identifying special or unique sites in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage area for inclusion in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003 / compiled by Kirstin Dobbs. ISBN 9781921682421 (pdf) Includes bibliographical references. Marine parks and reserves--Queensland--Management. Marine resources--Queensland--Management. Marine resources conservation--Queensland. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (Qld.)--Management. Dobbs, Kirstin Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. 333.916409943 This publication should be cited as: Dobbs, Kirstin (comp.) 2011, Identifying special or unique sites in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area for inclusion in the Great Barrier Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Director, Communications 2-68 Flinders Street PO Box 1379 TOWNSVILLE QLD 4810 Australia Phone: (07) 4750 0700 Fax: (07) 4772 6093 [email protected] Comments and inquiries on this document are welcome and should be addressed to: Director, Strategic Advice [email protected] www.gbrmpa.gov.au EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A comprehensive and adequate network of protected areas requires the inclusion of both representative examples of different habitats, and special or unique sites. -

Koala Context

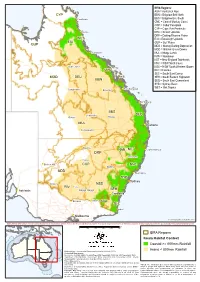

IBRA Regions: AUA = Australian Alps CYP BBN = Brigalow Belt North )" Cooktown BBS = Brigalow Belt South CMC = Central Mackay Coast COP = Cobar Peneplain CYP = Cape York Peninsula ") Cairns DEU = Desert Uplands DRP = Darling Riverine Plains WET EIU = Einasleigh Uplands EIU GUP = Gulf Plains GUP MDD = Murray Darling Depression MGD = Mitchell Grass Downs ") Townsville MUL = Mulga Lands NAN = Nandewar NET = New England Tablelands NNC = NSW North Coast )" Hughenden NSS = NSW South Western Slopes ") CMC RIV = Riverina SEC = South East Corner MGD DEU SEH = South Eastern Highlands BBN SEQ = South East Queensland SYB = Sydney Basin ") WET = Wet Tropics )" Rockhampton Longreach ") Emerald ") Bundaberg BBS )" Charleville )" SEQ )" Quilpie Roma MUL ") Brisbane )" Cunnamulla )" Bourke NAN NET ") Coffs Harbour DRP ") Tamworth )" Cobar ") Broken Hill COP NNC ") Dubbo MDD ") Newcastle SYB ") Sydney ") Mildura NSS RIV )" Hay ") Wagga Wagga SEH Adelaide ") ") Canberra ") ") Echuca Albury AUA SEC )" Eden ") Melbourne © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 INDICATIVE MAP ONLY: For the latest departmental information, please refer to the Protected Matters Search Tool and the Species Profiles & Threats Database at http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/index.html km 0 100 200 300 400 500 IBRA Regions Koala Habitat Context Coastal >= 800mm Rainfall Produced by: Environmental Resources Information Network (2014) Inland < 800mm Rainfall Contextual data source: Geoscience Australia (2006), Geodata Topo 250K Topographic Data and 10M Topographic Data. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2012). Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA), Version 7. Other data sources: Commonwealth of Australia, Bureau of Meteorology (2003). Mean annual rainfall (30-year period 1961-1990). Caveat: The information presented in this map has been provided by a Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2013). -

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Queensland's Biodiversity Under Climate Change: Ecological Scaling of Terrestrial Environmental Change Climate Adaptation Flagship Working Paper #12B

CLIMATE ADAPTATION FLAGSHIP Queensland's biodiversity under climate change: ecological scaling of terrestrial environmental change Climate Adaptation Flagship Working Paper #12B Simon Ferrier, Thomas D. Harwood and Kristen J. Williams September 2012 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Queensland's biodiversity under climate change: Ecological scaling of terrestrial environmental change / Simon Ferrier ISBN: 978-1-4863-0279-6 (pdf) Series: CSIRO Climate Adaptation Flagship Working Paper series; 12B. Other Tom Harwood and Kristen J. Williams Authors/Contributors: Climate Adaptation Flagship Enquiries Enquiries regarding this document should be addressed to: Kristen J Williams CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences GPO Box 1700, Canberra 2601 [email protected] Enquiries about the Climate Adaptation Flagship or the Working Paper series should be addressed to: Working Paper Coordinator CSIRO Climate Adaptation Flagship [email protected] Citation This document can be cited as: Ferrier, S., Harwood, T. and Williams, K.J. (2012) Queensland's biodiversity under climate change: Ecological scaling of terrestrial environmental change. CSIRO Climate Adaptation Flagship Working Paper No. 12B. http://www.csiro.au/resources/CAF-working-papers.html Acknowledgements This work has been funded by the Queensland Government and the CSIRO through the Climate Adaptation Flagship (Managing Species and Ecosystems Theme). The ecological scaling of terrestrial environmental change used the models and data described in Ferrier et al. (2010) and Williams et al. (2010a); the authors and acknowledgements therein apply also here. This manuscript was improved by comments from Michael Berkman (OCC), Craig James and Alistair Hobday, John Scott and Helen Murphy. Thanks to Serena Henry for proof reading. The Climate Adaptation Flagship Working Paper series The CSIRO Climate Adaptation National Research Flagship has been created to address the urgent national challenge of enabling Australia to adapt more effectively to the impacts of climate change and variability. -

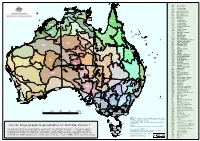

Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia, Version 7 Data Used Are Assumed to Be Correct As Received from the Data Suppliers

ARC Arnhem Coast ARP Arnhem Plateau TIW AUA Australian Alps AVW Avon Wheatbelt DARWIN BBN Brigalow Belt North ARC BBS Brigalow Belt South BEL Ben Lomond ITI DAC PCK ARP BHC Broken Hill Complex CEA BRT Burt Plain CAR Carnarvon ARC CEA Central Arnhem DAB CYP CEK Central Kimberley CER Central Ranges NOK VIB CHC Channel Country CMC Central Mackay Coast GUC COO Coolgardie GFU STU COP Cobar Peneplain COS Coral Sea CEK CYP Cape York Peninsula OVP DAB Daly Basin DAC Darwin Coastal DAL WET GUP EIU DAL Dampierland DEU Desert Uplands DMR Davenport Murchison Ranges COS DRP Darling Riverine Plains DMR TAN EIU Einasleigh Uplands MII ESP Esperance Plains GSD EYB Eyre Yorke Block FIN Finke FLB Flinders Lofty Block CMC FUR Furneaux BRT GAS Gascoyne PIL DEU GAW Gawler MGD BBN GES Geraldton Sandplains GFU Gulf Fall and Uplands MAC GID Gibson Desert LSD GID GSD Great Sandy Desert GUC Gulf Coastal GUP Gulf Plains CAR GAS CER FIN CHC GVD Great Victoria Desert HAM Hampton ITI Indian Tropical Islands SSD JAF Jarrah Forest KAN Kanmantoo KIN King GVD LSD Little Sandy Desert STP BBS MUR SEQ MAC MacDonnell Ranges MUL BRISBANE MAL Mallee MDD Murray Darling Depression YAL MGD GES Mitchell Grass Downs STP MII Mount Isa Inlier MUL Mulga Lands NUL MUR Murchison NAN Nandewar GAW NET NCP Naracoorte Coastal Plain SWA COO NAN NET New England Tablelands AVW HAM BHC DRP NNC NSW North Coast FLB NOK Northern Kimberley PERTH COP NSS NSW South Western Slopes MDD NNC NUL Nullarbor MAL EYB OVP Ord Victoria Plain PCK Pine Creek JAF ESP SYB PIL Pilbara ADELAIDE SYDNEY PSI PSI Pacific -

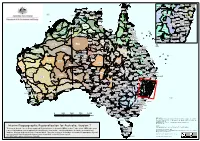

Terrestrial Protected Areas - IBRA Boundaries

Appendix 7 Terrestrial protected areas - IBRA boundaries AA Australian Alps TIW ARC Arnhem Coast Terrestrial Protected Areas - ARP Arnhem Plateau ARC AW Avon Wheatbelt 80,895,099 hectares (10.52%) BBN Brigalow Belt North DARWIN BBS Brigalow Belt South DAC ARP BEL Ben Lomond PCK CA BHC Broken Hill Complex BRT Burt Plain CA Central Arnhem DAB CYP CAR Carnarvon CHC Channel Country NK VB CK Central Kimberley GUC CMC Central Mackay Coast GFU COO Coolgardie STU CP Cobar Peneplain CR Central Ranges CK OVP CYP Cape York Peninsula DAB Daly Basin DL WT DAC Darwin Coastal GUP EIU DEU Desert Uplands DL Dampierland DMR Davenport Murchison Ranges DMR DRP Darling Riverine Plains TAN EIU Einasleigh Uplands MII ESP Esperance Plains GSD EYB Eyre Yorke Block FIN Finke FLB Flinders Lofty Block MGD BRT CMC FLI Flinders PIL DEU GAS Gascoyne BBN GAW Gawler GD Gibson Desert MAC GFU Gulf Fall and Uplands LSD GD GS Geraldton Sandplains GSD Great Sandy Desert CR FIN GUC Gulf Coastal CAR GAS GUP Gulf Plains CHC GVD Great Victoria Desert HAM Hampton SSD JF Jarrah Forest BBS KAN Kanmantoo SEQ KIN King STP ML LSD Little Sandy Desert MUR GVD BRISBANE MAC MacDonnell Ranges MAL Mallee MDD Murray Darling Depression GS YA L MGD Mitchell Grass Downs MII Mount Isa Inlier ML Mulga Lands NUL MUR Murchison NAN NAN Nandewar GAW DRP NET NCP Naracoorte Coastal Plain AW COO BHC NET New England Tablelands FLB NK Northern Kimberley PERTH HAM CP NNC NSW North Coast NSS NSW South Western Slopes SWA NNC MAL EYB NUL Nullarbor OVP Ord Victoria Plain JF SB PCK Pine Creek ESP NSS PIL Pilbara RIV SYDNEY RIV Riverina ADELAIDE SB Sydney Basin SEH ± WAR MDD SCP South East Coastal Plain 200100 0 200 400 KAN SEC South East Corner SEH South Eastern Highlands NCP AA SEQ South Eastern Queensland Kilometres VM SSD Simpson Strzelecki Dunefields Sources: STP Stony Plains IBRA 6.1 - IBRA Version 6.1 (2004), Australian Government Department of the Environment and VVP SEC STU Sturt Plateau Heritage through compilation of State/Territory SCP SWA Swan Coastal Plain datasets. -

Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia, Version 7 KIN01 Data Used Are Assumed to Be Correct As Received from the Data Suppliers

SEQ02 SEQ04 BBS17 BBS20 BBS19 BBS18 SEQ03 SEQ10 CYP03 SEQ11 TIW02 ARC05 NAN01 NET15 TIW01 ARC01 NNC02 CYP04 ARC02 BBS22 NET12 SEQ13 DAC01 DRP03 NET14 NNC18 ITI03 ARP01 BBS21 DARWIN ARC03 NET10 NET06 PCK01 ARP02 SEQ12 CEA02 NAN02 NET11 CEA01 CYP07 NET07 NNC03 NNC05 VIB02 NET17 ARC04 NET18 CYP01 NAN03 NET09 NNC04 DAB01 CYP09 NET01 NET05 NOK02 BBS23 NET16 NET08 NNC06 CYP08 NET04 VIB01 VIB03 CYP06 NAN04 NET13 NOK01 STU03 GUC02 NNC08 GFU01 GUC01 CYP02 NNC09 OVP03 NNC07 CYP05 BBS25 NNC10 GUP10 NET03 STU02 WET09 CEK01 GUP04 EIU03 CEK03 OVP01 GUP06 WET08 NNC11 GUP07 BBS24 OVP04 GFU02 WET07 NNC14 OVP02 STU01 GUP01 NNC12 DAL01 WET04 WET03 CEK02 GUP02 BBS26 NNC15 NNC13 DAL02 EIU02 EIU06 WET02 BBS27 MGD01 EIU01 NNC17 DMR01 GUP08 WET06 WET01 MII02 SYB01 WET05 NSS01 SYB02 NNC16 DMR03 GUP03 GUP05 EIU04 SYB04 TAN02 MGD02 GUP09 GSD01 TAN01 MII01 EIU05 BBN01 COS01 DMR02 MII03 CMC06 MGD06 PIL04 TAN03 DEU03 BBN02 GSD02 CMC01 BBN03 BBN04 PIL01 CMC02 BRT01 DEU01 BBN05 CHC01 MGD03 MGD07 DEU02 BRT02 BRT04 MGD05 BBN06 CMC03 LSD01 GSD05 GSD06 BBN07 PIL02 BRT03 MGD04 PIL03 GSD03 MAC03 BBN12 CAR01 GID02 MAC01 BBN09 BBN10 CMC04 DEU04 BBN11 BBN14 CMC05 GAS01 LSD02 MAC02 SSD01 BBN08 BBN13 GID01 GSD04 CHC03 BBS03 SEQ14 FIN01 MGD08 FIN02 SSD02 CHC04 BBS02 BBS05 BBS01 GAS03 CER01 BBS04 MUL09 BBS09 BBS06 BBS07 FIN03 SEQ01 CAR02 GAS02 BBS10 STP06 CHC02 BBS08 CHC05 FIN04 MUL06 SEQ08 MUL10 MUL04 BBS11 GVD04 CER03 STP05 CHC07 BBS12 SEQ07 MUR02 CER02 BBS13 STP01 MUL08 SEQ09 STP02 SSD03 SEQ05 CHC06 CHC08 BBS14 SEQ04 YAL01 GVD02 MUL02 SEQ06 MUL03 BBS16 BRISBANE MUR01 GVD05 STP04 -

Comprehensive, Adequate and Representative Reserve System for Forests in Australia

Nationally Agreed Criteria for the Establishment of a Comprehensive, Adequate and Representative Reserve System for Forests in Australia A Report by the Joint ANZECC / MCFFA National Forest Policy Statement Implementation Sub-committee Enquiries regarding ANZECC should be directed to The Secretary Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council C/- Environment Australia GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 Enquiries regarding MCFFA should be directed to The Secretary Ministerial Council on Forestry, Fisheries and Aquaculture C/- Department of Primary Industries and Energy GPO Box 858 Canberra ACT 2601 © Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISBN: 0 642 26670 0 Information presented in this document may be copied provided that full acknowledgment is made. FOREWORD For over two decades in Australia the competing demands of conservation and industry on our forests have been an area of debate and controversy. The National Forest Policy Statement (NFPS), agreed by the Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments, provides the framework for a long term solution to this issue. The NFPS sets out the process for undertaking joint Commonwealth and State/Territory Comprehensive Regional Assessments (CRAs) of natural and cultural, and economic and social values of Australia's forests as the basis for negotiation of Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs). RFAs are to be developed between the States/Territories and the Commonwealth and they will encompass the establishment and management of a forest reserve system which is comprehensive, adequate and representative (CAR), the ecologically sustainable management of forests outside the reserve system, and the development of an efficient, internationally competitive timber industry. The detailed information required to negotiate each RFA will be drawn together through a CRA of the full range of forest values of a region.