Von Hügel's Curiosity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthropology, Art & Museology Nicholas Thomas

Victoria University of Wellington A Critique ofA the Natural Critique Artefact of the GORDON H. BROWN LECTURE Natural Artefact: 132015 Anthropology, Art & Museology Nicholas Thomas PREVIOUS TITLES IN THIS SERIES Victoria University of Wellington A Critique of the GORDON H. BROWN LECTURE Natural Artefact: 132015 Anthropology, Art History Lecture Series 01 2003 Art History Lecture Series 08 2010 GORDON H. BROWN REX BUTLER Elements of Modernism in Colin McCahon in Australia Colin McCahon’s Early Work Art & Museology Art History Lecture Series 09 2011 Art History Lecture Series 02 2004 PAUL TAPSELL TONY GREEN The Art of Taonga Toss Woollaston: Origins and Influence Art History Lecture Series 10 2012 Nicholas Thomas Art History Lecture Series 03 2005 ROBERT LEONARD ROGER BLACKLEY Nostalgia for Intimacy A Nation’s Portraits Art History Lecture Series 11 2013 Art History Lecture Series 04 2006 ROSS GIBSON ANNIE GOLDSON Aqueous Aesthetics: An Art History of Change Memory, Landscape, Dad & Me Art History Lecture Series 12 2014 Art History Lecture Series 05 2007 DEIDRE BROWN, NGARINO ELLIS LEONARD BELL & JONATHAN MANE-WHEOKI In Transit: Questions of Home & Does Ma¯ori Art History Matter? Belonging in New Zealand Art Art History Lecture Series 06 2008 SARAH TREADWELL Rangiatea Revisited Art History Lecture Series 07 2009 MARY KISLER Displaced Legacies—European Art in New Zealand’s Public Collections Available on line at http://www.victoria.ac.nz/Art-History/down- loads/MaryKisler_lecture.pdf/ Preface Published by Art History, School of Art History, Classics This essay, the edited text of a lecture presented by Dr Nicholas Thomas, and Religious Studies addresses a key vehicle for the practice of art history: the museum. -

TRINITY COLLEGE Cambridge Trinity College Cambridge College Trinity Annual Record Annual

2016 TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge trinity college cambridge annual record annual record 2016 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2015–2016 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Contents 5 Editorial 11 Commemoration 12 Chapel Address 15 The Health of the College 18 The Master’s Response on Behalf of the College 25 Alumni Relations & Development 26 Alumni Relations and Associations 37 Dining Privileges 38 Annual Gatherings 39 Alumni Achievements CONTENTS 44 Donations to the College Library 47 College Activities 48 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 53 Field Clubs 71 Students’ Union and Societies 80 College Choir 83 Features 84 Hermes 86 Inside a Pirate’s Cookbook 93 “… Through a Glass Darkly…” 102 Robert Smith, John Harrison, and a College Clock 109 ‘We need to talk about Erskine’ 117 My time as advisor to the BBC’s War and Peace TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 3 123 Fellows, Staff, and Students 124 The Master and Fellows 139 Appointments and Distinctions 141 In Memoriam 155 A Ninetieth Birthday Speech 158 An Eightieth Birthday Speech 167 College Notes 181 The Register 182 In Memoriam 186 Addresses wanted CONTENTS TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 4 Editorial It is with some trepidation that I step into Boyd Hilton’s shoes and take on the editorship of this journal. He managed the transition to ‘glossy’ with flair and panache. As historian of the College and sometime holder of many of its working offices, he also brought a knowledge of its past and an understanding of its mysteries that I am unable to match. -

Displaying First Encounters Between Europeans and Pacific Islanders on the Voyages of Captain Cook, in Contemporary British Museums

Emma Yandle Objects of Encounter: Displaying first encounters between Europeans and Pacific Islanders on the voyages of Captain Cook, in contemporary British museums Figure 1. Māori trading a crayfish with Joseph Banks. By Tupaia, Figure 2. Joseph Banks trading with a Māori. Detail from In Pursuit of 1769. Venus [infected], by Lisa Reihana, 2015-2017. © Lisa Reihana. Emma Yandle Faculty of Humanities, University of Amsterdam Supervisor: prof. dr. R. (Rob) van der Laarse Second reader: dhr. dr. D.A. (David) Duindam Word count: 22,988 Emma Yandle Abstract This paper explores the presentation in contemporary British museums of the cross-cultural encounters that took place between Europeans and Indigenous Pacific Islanders, on the eighteenth-century voyages of Captain James Cook to the Pacific region. It takes as its central case studies four exhibitions that opened in London in 2018, in response to the 250th anniversary of Cook’s first voyage. It focuses on visualizations of encounters, ranging from British depictions created on the voyages, to the deployment of encounter iconography by contemporary Indigenous Pacific artists. Both are brought into relation with current anthropological conceptions of cross- cultural encounters: as contingent, tied to specific social locations, and with agency and complex motivations shared by both Indigenous and European actors. It analyses the extent to which the interpretative framing of these works reflects such dynamics of early Pacific encounters. It takes the view that eighteenth-century depictions of encounters are routinely deployed as documentary evidence within exhibitions, overlooking their imaginative construction. By comparison, the use of the same encounter iconography by contemporary Indigenous artists is subject to visual analysis and frequently brought into relation with anthropological ideas of encounters. -

Read Keith Thomas' the Wolfson History Prize 1972-2012

THE WOLFSON HISTORY PRIZE 1972-2012 An Informal History Keith Thomas THE WOLFSON HISTORY PRIZE 1972-2012 An Informal History Keith Thomas The Wolfson Foundation, 2012 Published by The Wolfson Foundation 8 Queen Anne Street London W1G 9LD www.wolfson.org.uk Copyright © The Wolfson Foundation, 2012 All rights reserved The Wolfson Foundation is grateful to the National Portrait Gallery for allowing the use of the images from their collection Excerpts from letters of Sir Isaiah Berlin are quoted with the permission of the trustees of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust, who own the copyright Printed in Great Britain by The Bartham Group ISBN 978-0-9572348-0-2 This account draws upon the History Prize archives of the Wolfson Foundation, to which I have been given unrestricted access. I have also made use of my own papers and recollections. I am grateful to Paul Ramsbottom and Sarah Newsom for much assistance. The Foundation bears no responsibility for the opinions expressed, which are mine alone. K.T. Lord Wolfson of Marylebone Trustee of the Wolfson Foundation from 1955 and Chairman 1972-2010 © The Wolfson Foundation FOREWORD The year 1972 was a pivotal one for the Wolfson Foundation: my father, Lord Wolfson of Marylebone, became Chairman and the Wolfson History Prize was established. No coincidence there. History was my father’s passion and primary source of intellectual stimulation. History books were his daily companions. Of all the Foundation’s many activities, none gave him greater pleasure than the History Prize. It is an immense sadness that he is not with us to celebrate the fortieth anniversary. -

Reading Middle English: Some Resources

Reading Middle English: Some Resources This document is intended to direct you towards some resources for reading and working with Middle English that you will find useful throughout the MPhil. Late-medieval Europe had an exceptionally complex linguistic ecology, with a spectrum of vernacular languages interacting with the linguae francae of Latin and the different forms of French used all the way from Britain to the eastern Mediterranean. Medieval England, as well as boasting an exceptionally long history of writings in the vernacular in the centuries before the Norman Conquest, was a place in which languages met and interacted: the distinctive language that scholarship calls ‘Middle English’ emerged from this linguistic mix (although the development of the modern scholarly idea of Middle English has its own complex history — on which see Matthews towards the bottom of this list). In the MPhil, you will be encountering writings in English, French, and Latin. Separate resources are provided for French and Latin, but, as some of the studies in the final section of this book suggest, it is impossible to think about the language and culture of medieval England without thinking seriously about all three of its main written languages. Before the MPhil begins, you should try to have a look at least one of the introductions to Middle English listed below if you can, and play around with some of the dictionaries, too. As you read more writings in Middle English, don’t forget that good-quality editions (e.g. the editions produced for the Early English Text Society, with their distinctive mud- brown livery) are excellent resources for the study of language: through their introductions, their explanatory notes, and (the first port of call for a mystified reader) their glossaries. -

Exhibiting Indigenous Australian Collections in the UK

Exhibiting Indigenous Australian collections in the UK Rachael Murphy Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD. University of East Anglia. Sainsbury Research Unit, February 2017 Text and bibliography: 69332 words. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 1 Abstract This thesis asks: what are the uses and meanings of Indigenous Australian collections in the UK today? This question is approached through a comprehensive analysis of one exhibition, Indigenous Australia: enduring civilisation, which took place at the British Museum (BM), London, from 23 April to 2 August, 2015. Each chapter considers a different stage of the exhibition’s development and reception. It begins in Chapter 2. Genealogy with a study of how the exhibition emerged from the longer history of collecting and displaying Indigenous Australian material at the BM. It then interrogates the aims and experiences of the people who made Indigenous Australia in Chapter 3. Production. Chapter 4. Text analyses the finished display and, Chapter 5. Consumption, evaluates how the exhibition was received by its audiences. Each chapter considers not only how the exhibition was experienced by the people involved, but also how their aims and understandings relate to broader debates about the role of colonial era collections in contemporary Western societies. 2 Acknowledgements Thank you to the AHRC for funding this project, and to the Sainsbury Research Unit for Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas and University of East Anglia for additional travel and conference funds. -

Introduction 1

Notes Introduction 1. J. E. Cookson, The British Armed Nation, 1793–1815 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1997), v. 2. Christopher Lloyd, The British Seaman, 1200–1860: A Social Survey (Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1968), 123. 3. H. V. Bowen, War and British Society, 1688–1815 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 3. 4. Alan Forrest, Conscripts and Deserters: The Army and French Society dur- ing the Revolution and Empiree (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989). 5. John Brewer, The Sinews of Power: War, Money and the English State, 1688–1783 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990); Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707–18377 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992). 6. HO/28/40: Lieut. Comm. Thomas Hawkes to J. W. Croker, 15 Aug 1811. 7. HO 28/7: R. Dawson, Lt. Governor of the Isle of Man, to Grenville, 20 July 1790. 8. The best studies of impressment are likely to be local histories for this reason. Keith Mercer, “Sailors and Citizens: Press Gangs and Naval- Civilian Relations in Nova Scotia, 1756–1815,” Journal of Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society 10 (2007): 87–113; Keith Mercer, “The Murder of Lieutenant Lawry: A Case Study of British Naval Impressment in Newfoundland, 1794,” Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 21, no. 2 (2006): 255–289. 9. HO 28/7: R. Dawson to Grenville, 20 July 1790; HO 28/24: Evan Nepean to John King, 11 July 1798; HO 28/34: John Barrow to J. Beckett, 1 September 1807; HO 28/40, John Barrow to J. Beckett, 21 August 1811. This simmering sense of injustice helps provide context for similar (but less clearly explained) violent episodes else- where, such as the ones witnessed by the young William Lovett in his Cornish fishing village. -

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

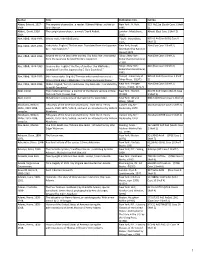

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel. -

Annual Report 2001-02

Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU t 020 7862 8740 f 020 7862 8745 [email protected] Annual Report 2001-2002 University of London SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY 1 Table of Contents Board, Staff, Fellows and Associates of the Institute.......................................................................... 4 Members of the Institute of Historical Research Advisory Council ................................................................................ 4 Staff of the Institute of Historical Research ...................................................................................................................... 5 Fellows of the Institute of Historical Research............................................................................................................... 10 Reports .................................................................................................................................................... 13 Librarian’s Report.......................................................................................................................................................... 15 Victoria County History – Director and General Editor’s Report.................................................................................. 16 Centre for Metropolitan History – Director’s Report ..................................................................................................... 16 Institute of Contemporary British History – Director’s Report...................................................................................... -

Section Membership

SECTIONS 81 Section membership Fellows are assigned to a ‘Section of primary allegiance’ of their choice. It is possible to belong to more than one Section (cross-membership, by invitation of the Section concerned); this is approved by Council, the members to serve for a period of five years. In the following pages cross-members are listed after primary members, together with their primary Section and the date of appointment. The Emeritus Fellows of each Section are also listed separately. And the primary affiliation of Corresponding Fellows is also indicated. Membership of the Ginger Groups is listed on page 97. * Indicates membership of Section Standing Committee. -

Objects As Polyagents: Tracing the Histories of the Gweagal Spears

Objects As Polyagents: Tracing The Histories Of The Gweagal Spears Francesca H. Dakin Corpus Christi College Word Count: 12,994 Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the MPhil in Social Anthropology, 2018-19. I declare that this dissertation is substantially my own work. Where reference is made to the works of others the extent to which that work has been used is indicated and duly acknowledged in the text and bibliography. Acknowledgements Thank you to my supervisor, Anita Herle, for being so patient with me throughout my research and write-up. Were it not for her, this paper would be much longer and even less clear. I also thank all of the people that provided me with such rich and unbounded fieldwork opportunities. I thank all who contributed to this dissertation through sharing their perspectives, time, and research. These include Rodney Kelly, Shayne Williams, Anita Herle, Mark Elliott, Nicholas Thomas, and all those present at the various protests, talks, and conferences surrounding the Gweagal spears and repatriation. Finally, I thank the friends that I have been privileged to spend this past year with; c'était bon. 1 Contents Introduction 3 Theory and Fieldwork 5 The Social Lives of The Gweagal Spears 11 Ownership and Repatriation 18 Rejection and Protest 26 Conclusion: Polyagents in the Relational Museum 39 References 43 Appendices 50 Figures Figure 1: The Gweagal Spears 11 Figure 2: The Voyages cabinet 13 Figure 3: D.1914.1 and D.1914.4 14 Figure 4: The Australia cabinet 15 Figure 5: Members of the Sub-Committee 27 Figure 6: Official statement from the University 28 Figure 7: Rodney Kelly with the Gweagal spears 35 2 Introduction This paper explores the capacity for objects entangled in complex - and often painful - histories to become constituted of multiple agencies (Gell 1998) through their interaction with various actants in complex and ever-expanding networks of association (Latour 1993; 2005).