Beta Blockers Reassessing Pharmacological Differences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acebutolol Hydrochloride Eq 200 Mg Base, Capsule, Oral, 100 0.4612 B Eq 400 Mg Base, Capsule, Oral, 100 0.6713 B

TRANSMITTAL NO. 37 - FEDERAL UPPER LIMIT DRUG LIST NOVEMBER 20, 2001 The following list of multiple source drugs meets the criteria set forth in 42 CFR 447.332 and Section 1927(e) of the Social Security Act, as amended by OBRA 1993. Payment for multiple source drugs identified and listed below must not exceed, in the aggregate, payment levels determined by applying to each drug entity a reasonable dispensing fee (established by the State and specified in the State plan), plus an amount based on the limit per unit which CMS has determined to be equal to 150 percent applied to the lowest price listed (in package sizes of 100 units, unless otherwise noted) in any of the published compendia of cost information of drugs. The listing is based on data current as of April 2001 from First Data Bank (Blue Book), Medi- Span, and the Red Book. This list does not reference the commonly known brand names. However, the brand names are included in the electronic FUL listing provided to the state agencies. The FUL price list and electronic listing are available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/Reimbursement/05_FederalUpperLimits.asp. In accordance with current policy, Federal financial participation will not be provided for any drug on the FUL listing for which the FDA has issued a notice of an opportunity for a hearing as a result of the Drug Efficacy Study and Implementation (DESI) program, and which has been found to be a less than effective or is identical, related or similar (IRS) to the DESI drug. The DESI drug is identified by the Food and Drug Administration or reported by the drug manufacturer for purposes of the Medicaid drug rebate program. -

Therapeutic Class Overview Beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents

Therapeutic Class Overview Beta-adrenergic Blocking Agents INTRODUCTION Approximately 92.1 million American adults have at least 1 type of cardiovascular disease according to the American Heart Association (AHA) Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics 2018 update. From 2003 to 2015, mortality associated with cardiovascular disease declined 25.5% (Benjamin et al 2018). Beta-adrenergic blocking agents (beta-blockers) are a group of drugs that block the sympathomimetic effects of catecholamines on beta receptors. This results in negative inotropic and chronotropic effects and relaxation of smooth muscle. Beta-blockers have varied pharmacologic properties. ○ Cardioselective beta-blockers preferentially interact with beta1-receptors, which are predominantly found in the heart. Non-cardioselective beta-blockers also interact with beta2-receptors found on smooth muscle in the lungs, blood vessels, and other tissues. The cardioselectivity of beta-blockers is dose dependent; therefore, beta2 blockade can occur at higher doses with certain cardioselective agents. ○ Some beta-blockers (acebutolol and pindolol) have intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (ISA), which may result in a lower incidence of bradycardia and bronchoconstriction (Facts and Comparisons 2018). In addition, some beta- blockers (nebivolol and propranolol) have higher lipophilicity, which may increase the risk for central nervous system- related adverse events (Facts and Comparisons 2018). ○ Carvedilol and labetalol also block alpha-adrenergic receptors and may reduce peripheral resistance more than other beta-blockers (Clinical Pharmacology 2018). Specific indications for the beta-blockers vary by product. Most beta-blockers (all except sotalol) are approved to treat hypertension (HTN). The 2017 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/AHA clinical practice guideline defines HTN as blood pressure (BP) ≥ 130/80 mm Hg (Whelton et al 2017). -

Migraine Headache Prophylaxis Hien Ha, Pharmd, and Annika Gonzalez, MD, Christus Santa Rosa Family Medicine Residency Program, San Antonio, Texas

Migraine Headache Prophylaxis Hien Ha, PharmD, and Annika Gonzalez, MD, Christus Santa Rosa Family Medicine Residency Program, San Antonio, Texas Migraines impose significant health and financial burdens. Approximately 38% of patients with episodic migraines would benefit from preventive therapy, but less than 13% take prophylactic medications. Preventive medication therapy reduces migraine frequency, severity, and headache-related distress. Preventive therapy may also improve quality of life and prevent the progression to chronic migraines. Some indications for preventive therapy include four or more headaches a month, eight or more headache days a month, debilitating headaches, and medication- overuse headaches. Identifying and managing environmental, dietary, and behavioral triggers are useful strategies for preventing migraines. First-line med- ications established as effective based on clinical evidence include divalproex, topiramate, metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol. Medications such as ami- triptyline, venlafaxine, atenolol, and nadolol are probably effective but should be second-line therapy. There is limited evidence for nebivolol, bisoprolol, pindolol, carbamazepine, gabapentin, fluoxetine, nicardipine, verapamil, nimodipine, nifedipine, lisinopril, and candesartan. Acebutolol, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, and telmisartan are ineffective. Newer agents target calcitonin gene-related peptide pain transmission in the migraine pain pathway and have recently received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; how- ever, more studies of long-term effectiveness and adverse effects are needed. The complementary treatments petasites, feverfew, magnesium, and riboflavin are probably effective. Nonpharmacologic therapies such as relaxation training, thermal biofeedback combined with relaxation training, electromyographic feedback, and cognitive behavior therapy also have good evidence to support their use in migraine prevention. (Am Fam Physician. 2019; 99(1):17-24. -

IEHP Dualchoice Cal Mediconnect Formulary Maintenance Drug List

IEHP DualChoice Cal MediConnect (Medicare-Medicaid Plan) Formulary Maintenance Drug List The following formulary medications may be approvable up to a three-month supply. Certain medications on this list may require prior approval from the plan based on existing criteria before being covered. For coverage information please see our formulary located on our website. BRAND GENERIC STREGTH DOSAGE FORM ABACAVIR ABACAVIR SULFATE 300 MG TABLET ABACAVIR ABACAVIR SULFATE 20 MG/ML SOLUTION TRIUMEQ ABACAVIR SULFATE/DOLUTEGRAVIR 600-50-300 TABLET SODIUM/LAMIVUDINE ABACAVIR-LAMIVUDINE ABACAVIR SULFATE/LAMIVUDINE 600-300MG TABLET ABACAVIR-LAMIVUDINE- ABACAVIR SULFATE/LAMIVUDINE/ZIDOVUDINE 150-300 MG TABLET ZIDOVUDINE TYMLOS ABALOPARATIDE 80MCG/DOSE PEN INJCTR ORENCIA ABATACEPT 125 MG/ML SYRINGE ORENCIA CLICKJECT ABATACEPT 125 MG/ML AUTO INJCT ORENCIA ABATACEPT 50MG/0.4ML SYRINGE ORENCIA ABATACEPT 87.5MG/0.7 SYRINGE VERZENIO ABEMACICLIB 50 MG TABLET VERZENIO ABEMACICLIB 100 MG TABLET VERZENIO ABEMACICLIB 150 MG TABLET VERZENIO ABEMACICLIB 200 MG TABLET ABIRATERONE ACETATE ABIRATERONE ACETATE 500 MG TABLET ABIRATERONE ACETATE ABIRATERONE ACETATE 250 MG TABLET YONSA ABIRATERONE ACETATE, SUBMICRONIZED 125 MG TABLET CALQUENCE ACALABRUTINIB 100 MG CAPSULE ACAMPROSATE CALCIUM ACAMPROSATE CALCIUM 333 MG TABLET DR ACARBOSE ACARBOSE 25 MG TABLET ACARBOSE ACARBOSE 50 MG TABLET ACARBOSE ACARBOSE 100 MG TABLET ACEBUTOLOL HCL ACEBUTOLOL HCL 200 MG CAPSULE ACEBUTOLOL HCL ACEBUTOLOL HCL 400 MG CAPSULE ACETAZOLAMIDE ER ACETAZOLAMIDE 500 MG CAPSULE ER ACETAZOLAMIDE -

Therapeutic Drug Class

EFFECTIVE Version Department of Vermont Health Access Updated: 06/05/20 Pharmacy Benefit Management Program /2016 Vermont Preferred Drug List and Drugs Requiring Prior Authorization (includes clinical criteria) The Commissioner for Office of Vermont Health Access shall establish a pharmacy best practices and cost control program designed to reduce the cost of providing prescription drugs, while maintaining high quality in prescription drug therapies. The program shall include: "A preferred list of covered prescription drugs that identifies preferred choices within therapeutic classes for particular diseases and conditions, including generic alternatives" From Act 127 passed in 2002 The following pages contain: • The therapeutic classes of drugs subject to the Preferred Drug List, the drugs within those categories and the criteria required for Prior Authorization (P.A.) of non-preferred drugs in those categories. • The therapeutic classes of drugs which have clinical criteria for Prior Authorization may or may not be subject to a preferred agent. • Within both categories there may be drugs or even drug classes that are subject to Quantity Limit Parameters. Therapeutic class criteria are listed alphabetically. Within each category the Preferred Drugs are noted in the left-hand columns. Representative non- preferred agents have been included and are listed in the right-hand column. Any drug not listed as preferred in any of the included categories requires Prior Authorization. Approval of non-preferred brand name products may require trial and failure of at least 2 different generic manufacturers. GHS/Change Healthcare Change Healthcare GHS/Change Healthcare Sr. Account Manager: PRESCRIBER Call Center: PHARMACY Call Center: Michael Ouellette, RPh PA Requests PA Requests Tel: 802-922-9614 Tel: 1-844-679-5363; Fax: 1-844-679-5366 Tel: 1-844-679-5362 Fax: Note: Fax requests are responded to within 24 hrs. -

Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated With

Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated with Tinnitus American Tinnitus Association Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated with Tinnitus All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of the American Tinnitus Association. ©2013 American Tinnitus Association Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated with Tinnitus American Tinnitus Association This document is to be utilized as a conversation tool with your health care provider and is by no means a “complete” listing. Anyone reading this list of ototoxic drugs is strongly advised NOT to discontinue taking any prescribed medication without first contacting the prescribing physician. Just because a drug is listed does not mean that you will automatically get tinnitus, or exacerbate exisiting tinnitus, if you take it. A few will, but many will not. Whether or not you eperience tinnitus after taking one of the listed drugs or herbals, or after being exposed to one of the listed chemicals, depends on many factors ‐ such as your own body chemistry, your sensitivity to drugs, the dose you take, or the length of time you take the drug. It is important to note that there may be drugs NOT listed here that could still cause tinnitus. Although this list is one of the most complete listings of drugs associated with tinnitus, no list of this kind can ever be totally complete – therefore use it as a guide and resource, but do not take it as the final word. The drug brand name is italicized and is followed by the generic drug name in bold. -

Randomised Study of Six Beta-Blockers and a Thiazide Diuretic in Essential Hypertension

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL 5 AUGUST 1978 383 AND ORIGINALS PAPERS Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.2.6134.383 on 5 August 1978. Downloaded from Randomised study of six beta-blockers and a thiazide diuretic in essential hypertension R G WILCOX British Medical_Journal, 1978, 2, 383-385 pranolol, and timolol-and a thiazide diuretic. These beta- blockers offered various ancillary properties, such as cardio- selectivity (atenolol), partial cardioselectivity (acebutolol), Summary and conclusions intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (acebuiolol and pindolol), and membrane-stabilising activity (acebutolol, labetalol, pro- Atenolol was compared with five other beta-blockers pranolol, and pindolol). In addition, the effects of the alpha- and a thiazide diuretic in a randomised cross-over trial blocking and beta-blocking properties of labetalol could be of once-daily treatment of essential hypertension. compared with those of the conventional beta-blockers. Atenolol was significantly better at reducing resting The diuretic used is often regarded as the drug of first choice and exercise blood pressures at 24 hours than any of the in hypertension; it is much cheaper than any available beta- http://www.bmj.com/ other drugs and had a low incidence of side effects. Both blocker and has been used for years as a once-daily treatment of timolol and acebutolol had a significant hypotensive mild essential hypertension. effect at 24 hours and a low incidence of side effects, suggesting that further increases in dosage might be effective and well tolerated. Labetalol proved ineffective when given once daily, and the high incidence of side Patients and methods effects, equalled only by pindolol, would probably Patients attending an outpatient clinic for uncomplicated essential prohibit further increases in dosage. -

Acebutolol 400 Mg Film-Coated Tablets

If you are not sure if any of the above apply to Package leaflet: you, talk to your doctor or pharmacist before Information for the user taking Acebutolol. Operations or anaesthetics Acebutolol 400 mg Tell your doctor or dentist you are taking film-coated tablets Acebutolol if you are going to have an anaesthetic or an operation (including dental acebutolol hydrochloride surgery). Other medicines and Acebutolol Tell your doctor or pharmacist if you are taking, Read all of this leaflet carefully before have recently taken or might take any other you start taking this medicine because it medicines. contains important information for you. In particular, tell your doctor if you are taking • Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it any of the following: again. - Other medicines for high blood pressure • If you have any further questions, ask your - Clonidine used for migraine or high blood doctor or pharmacist. pressure. If you are taking clonidine and • This medicine has been prescribed for you Acebutolol together, you should not stop only. Do not pass it on to others. It may taking clonidine unless your doctor tells you. harm them, even if their signs of illness are If you have to stop taking clonidine, your the same as yours. doctor will give you instructions • If you get any side effects, talk to your - Medicines for chest pain (angina) such as doctor or pharmacist. This includes any verapamil, nifedipine or diltiazem. Verapamil possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. must not be taken within several days of See section 4. taking Acebutolol What is in this leaflet - Medicines for heart problems such as 1. -

BETA BLOCKERS PA SUMMARY PREFERRED All Generic Products

BETA BLOCKERS PA SUMMARY PREFERRED All generic products except those noted, acebutolol HCl, atenolol, betaxolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol, Corzide, labetolol, Levatol, Lopressor HCT, metoprolol succinate ER, metoprolol tartrate, nadolol, pindolol, propranolol HCl, Sorine, sotalol, sotalol AF, Timolide, timolol maleate NON-PREFERRED All branded products with generics available except those noted, Betapace, Betapace AF, Bystolic, Coreg, Coreg CR, Corgard, Inderal, Inderal LA, Innopran XL, Kerlone, Lopressor, Metoprolol/HCTZ, Nadolol/bendroflumethiazide, Sectral, Tenormin,Toprol XL, Trandate, Zebeta LENGTH OF AUTHORIZATION: 1 Year NOTE: All members who had received a non-preferred medication in this category, at the time this criteria was adopted, were grandfathered on that medication. The member must have had at least one claim for the requested non-preferred product within the last 12 months of claims history. Physicians discharging a member from an inpatient facility stable and responding to a non-preferred agent should request prior authorization as part of the patient’s discharge planning. PA CRITERIA: For Innopran XL, member should have tried or failed propranolol or physician should submit documentation of a history of intolerable side effects to propranolol. For Coreg CR, member should have tried and failed carvedilol (Coreg) or physician should submit documentation of a history of intolerable side effects to carvedilol (Coreg). For Metoprolol HCTZ, member should have tried and failed Lopressor HCT or physician should submit documentation of a history of intolerable side effects to Lopressor HCT. For nadolol/bendroflumethiazide, member should have tried and failed Corzide or physician should submit documentation of a history of intolerable side effects to Corzide. For Bystolic, physician should submit documentation of allergies, contraindications, drug-drug interactions, history of intolerable side effects, or failure to achieve the desired clinical endpoints with at least two preferred beta blockers. -

2019 Prohibited List

THE WORLD ANTI-DOPING CODE INTERNATIONAL STANDARD PROHIBITED LIST JANUARY 2019 The official text of the Prohibited List shall be maintained by WADA and shall be published in English and French. In the event of any conflict between the English and French versions, the English version shall prevail. This List shall come into effect on 1 January 2019 SUBSTANCES & METHODS PROHIBITED AT ALL TIMES (IN- AND OUT-OF-COMPETITION) IN ACCORDANCE WITH ARTICLE 4.2.2 OF THE WORLD ANTI-DOPING CODE, ALL PROHIBITED SUBSTANCES SHALL BE CONSIDERED AS “SPECIFIED SUBSTANCES” EXCEPT SUBSTANCES IN CLASSES S1, S2, S4.4, S4.5, S6.A, AND PROHIBITED METHODS M1, M2 AND M3. PROHIBITED SUBSTANCES NON-APPROVED SUBSTANCES Mestanolone; S0 Mesterolone; Any pharmacological substance which is not Metandienone (17β-hydroxy-17α-methylandrosta-1,4-dien- addressed by any of the subsequent sections of the 3-one); List and with no current approval by any governmental Metenolone; regulatory health authority for human therapeutic use Methandriol; (e.g. drugs under pre-clinical or clinical development Methasterone (17β-hydroxy-2α,17α-dimethyl-5α- or discontinued, designer drugs, substances approved androstan-3-one); only for veterinary use) is prohibited at all times. Methyldienolone (17β-hydroxy-17α-methylestra-4,9-dien- 3-one); ANABOLIC AGENTS Methyl-1-testosterone (17β-hydroxy-17α-methyl-5α- S1 androst-1-en-3-one); Anabolic agents are prohibited. Methylnortestosterone (17β-hydroxy-17α-methylestr-4-en- 3-one); 1. ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROIDS (AAS) Methyltestosterone; a. Exogenous* -

1.3.1 SPC, Labelling and Package Leaflet MARKETING

1.3.1 SPC, Labelling and Package Leaflet SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Acebutolol Aurobindo 200 mg film-coated tablets Acebutolol Aurobindo 400 mg film-coated tablets 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each film-coated tablet contains 200 mg of acebutolol (as acebutolol hydrochloride) Each film-coated tablet contains 400 mg of acebutolol (as acebutolol hydrochloride) Excipients with known effect: Each 200 mg film-coated tablet contains 26 mg lactose monohydrate Each 400 mg film-coated tablet contains 52 mg lactose monohydrate For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Film-coated tablet. Acebutolol 200mg Film Coated Tablets: White to off-white, round shaped biconvex film coated tablets of 10.1 mm debossed with ‘AC’ and ‘2’ separated with breakline on one side and plain on the other side. Acebutolol 400mg Film Coated Tablets: White to off-white, oblong shaped biconvex film coated tablets having the length approximately 17.15 mm, diameter of body approximately 8.42 mm debossed with ‘AC’ and ‘4’ separated with breakline on one side and plain on the other side. The tablet can be divided into equal doses 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications The management of hypertension, angina pectoris and the control of tachyarrhythmias. 4.2 Posology and method of administration Posology The dose and treatment duration should be based on the individual response and should be adequately monitored by the treating physician. If long-term treatment will be discontinued, withdrawal of treatment by betablockers should be achieved by gradual dosage reduction. Hypertension: MARKETING AUTHORISATION APPLICATION Acebutolol Aurobindo 200mg and 400 mg film coated tablets 1.3.1 SPC, Labelling and Package Leaflet The usual initial daily dose is 400 mg. -

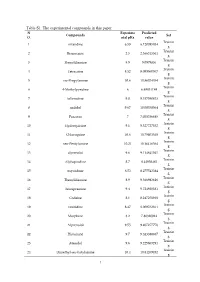

Table S1. the Experimental Compounds in This Paper N Experime Predicted Compounds Set O

Table S1. The experimental compounds in this paper N Experime Predicted Compounds Set O. ntal pKa value Trainin 1 nizatidine 6.59 6.120085934 g Trainin 2 Benzocaine 2.5 2.366315561 g Trainin 3 Thenyldiamine 8.9 9.0979836 g Trainin 4 Tetracaine 8.52 8.099960067 g Trainin 5 iso-Propylamine 10.6 10.86074354 g Trainin 6 4-Methylpyridine 6 6.48831189 g Trainin 7 tolterodine 9.8 9.317040813 g Trainin 8 nadolol 9.67 10.00358564 g Trainin 9 Prazosin 7 7.038356685 g Trainin 10 Hydroquinine 9.1 9.327727352 g Trainin 11 Chloroquine 10.6 10.79803548 g Trainin 12 neo-Pentylamine 10.21 10.16416564 g Trainin 13 alprenolol 9.6 9.114841045 g Trainin 14 Alphaprodine 8.7 8.44958465 g Trainin 15 oxycodone 8.53 8.275543384 g Trainin 16 Thenyldiamine 8.9 9.366983616 g Trainin 17 Trimipramine 9.4 9.724920331 g Trainin 18 Codeine 8.1 8.247258918 g Trainin 19 ranitidine 8.47 8.009762811 g Trainin 20 Morphine 8.2 7.86320014 g Trainin 21 Alprenolol 9.55 9.407277776 g Trainin 22 Histamine 9.7 9.323388837 g Trainin 23 Atenolol 9.6 9.225603291 g Trainin 24 Dimethyl-sec-butylamine 10.4 10.84269492 g 1 Trainin 25 trimipramine 9.24 9.246298648 g Trainin 26 clomipramine 9.38 9.71405201 g Trainin 27 Ethylamine 10.9 11.32834788 g Trainin 28 Acyclovir 2.2 1.802964981 g Trainin 29 Niacine- 4.8 4.936141249 g Trainin 30 Cyclohexylamine 10.6 11.07925925 g Trainin 31 Lidocaine 7.92 8.312245133 g Trainin 32 n-Butylamine 10.8 10.70137758 g Trainin 33 di-iso-Propylamine 11.1 10.94549528 g Trainin 34 nicotine 8.1 8.37598679 g Trainin 35 Dimethyl-n-butylamine 10.02 9.766578946 g Trainin