Eludamos.Org

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

Full Version

Volume 11, Number 2 Spring 2020 Contents ARTICLES Reexploring the Esports Approach of America’s Three Major Leagues Peter A. Carfagna.................................................. 115 The NCAA’s Agent Certification Program: A Critical and Legal Analysis Marc Edelman & Richard Karcher ..................................... 155 Well-Intentioned but Counterproductive: An Analysis of the NFLPA’s Financial Advisor Registration Program Ross N. Evans ..................................................... 183 A Win Win: College Athletes Get Paid for Their Names, Images, and Likenesses, and Colleges Maintain the Primacy of Academics Jayma Meyer and Andrew Zimbalist ................................... 247 Harvard Journal of Sports & Entertainment Law Student Journals Office, Harvard Law School 1585 Massachusetts Avenue, Suite 3039 Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 495-3146; [email protected] www.harvardjsel.com U.S. ISSN 2153-1323 The Harvard Journal of Sports & Entertainment Law is published semiannually by Harvard Law School students. Submissions: The Harvard Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law welcomes articles from professors, practitioners, and students of the sports and entertainment industries, as well as other related disciplines. Submissions should not exceed 25,000 words, including footnotes. All manuscripts should be submitted in English with both text and footnotes typed and double-spaced. Footnotes must conform with The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (20th ed.), and authors should be prepared to supply any cited sources upon request. All manu- scripts submitted become the property of the JSEL and will not be returned to the author. The JSEL strongly prefers electronic submissions through the ExpressO online submission system at http://www.law.bepress.com/expresso or the Scholastica online submission system at https://harvard-journal-sports-ent-law.scholasticahq.com. -

UPDATE NEW GAME !!! the Incredible Adventures of Van Helsing + Update 1.1.08 Jack Keane 2: the Fire Within Legends of Dawn Pro E

UPDATE NEW GAME !!! The Incredible Adventures of Van Helsing + Update 1.1.08 Jack Keane 2: The Fire Within Legends of Dawn Pro Evolution Soccer 2013 Patch PESEdit.com 4.1 Endless Space: Disharmony + Update v1.1.1 The Curse of Nordic Cove Magic The Gathering Duels of the Planeswalkers 2014 Leisure Suit Larry: Reloaded Company of Heroes 2 + Update v3.0.0.9704 Incl DLC Thunder Wolves + Update 1 Ride to Hell: Retribution Aeon Command The Sims 3: Island Paradise Deadpool Machines at War 3 Stealth Bastard GRID 2 + Update v1.0.82.8704 Pinball FX2 + Update Build 210613 incl DLC Call of Juarez: Gunslinger + Update v1.03 Worms Revolution + Update 7 incl. Customization Pack DLC Dungeons & Dragons: Chronicles of Mystara Magrunner Dark Pulse MotoGP 2013 The First Templar: Steam Special Edition God Mode + Update 2 DayZ Standalone Pre Alpha Dracula 4: The Shadow of the Dragon Jagged Alliance Collectors Bundle Police Force 2 Shadows on the Vatican: Act 1 -Greed SimCity 2013 + Update 1.5 Hairy Tales Private Infiltrator Rooks Keep Teddy Floppy Ear Kayaking Chompy Chomp Chomp Axe And Fate Rebirth Wyv and Keep Pro Evolution Soccer 2013 Patch PESEdit.com 4.0 Remember Me + Update v1.0.2 Grand Ages: Rome - Gold Edition Don't Starve + Update June 11th Mass Effect 3: Ultimate Collectors Edition APOX Derrick the Deathfin XCOM: Enemy Unknown + Update 4 Hearts of Iron III Collection Serious Sam: Classic The First Encounter Castle Dracula Farm Machines Championships 2013 Paranormal Metro: Last Light + Update 4 Anomaly 2 + Update 1 and 2 Trine 2: Complete Story ZDSimulator -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

By Vince Shuley Born in a Burnaby Basement Three Decades Ago, British Columbia's Joystick Grip on the Global Video-Game Indust

BORN IN A BURNABY BASEMENT THREE DECADES AGO, BRITISH COLUMBIA’S JOYSTICK GRIP ON THE GLOBAL VIDEO-GAME INDUSTRY SEEMED UNTOUCHABLE. BUT FIERCE COMPETITION, BRAIN DRAINS AND THE FREEMIUM-FUELLED REALITIES OF THE NEW NETSCAPE HAVE BUMPED BC INTO THE BACKSEAT. FROM EA TO INDIE, WE CHRONICLE THE PROVINCE’S REMARKABLE ROLE IN THIS MAMMOTH DIGITAL BUSINESS AND FIND THAT THE GAME IS IN FACT, NOT OVER. Sember and Mattrick BY VINCE SHULEY when the subject of Canada’s greatest cultural but the foundations were laid by ambitious young Vancouverites. exports arises, video games are probably not the first thought that Two Burnaby schoolboys had the smarts and business sense comes to mind. However, more than music, television or film, to hatch Vancouver’s vibrant game industry 30 years ago. Don Canadian video games are bought and played by more people, in Mattrick and Jeff Sember began designing and selling digital com- more places, all over the world. Since the beginning of this medium, puter games out of their living rooms in the early 80s, and their Vancouver has sat at the center of video-game development and first published title, Evolution, was the first commercially successful innovation in the electronic world. From lone-ranger independents game ever made in Canada. After selling 400,000 copies, which paid (indies) to army-sized studios, video-game development companies for both their university tuitions, as well as a couple of shiny sports in Vancouver employ some of the most talented folks in the digital- cars, the teenagers formed Distinctive Software Incorporated (DSI) media industry. -

Redline GT Compatible Games

Redline GT Compatible Games PlayStation®2 PlayStation®2 (con't) 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker ™ NASCAR® 07 Auto Modellista NASCAR® 08 Burnout 2: Point of Impact™ NASCAR® 09 Burnout 3 Takedown™ NASCAR® 2005: Chase for the Cup™ Burnout™ NASCAR® Heat™ 2: Road To The Championship Burnout™ Dominator NASCAR® Heat™ 2002 Burnout™ Revenge NASCAR® Thunder™ 2002 Colin McRae™ 2005 NASCAR® Thunder™ 2003 Colin McRae™ 3 NASCAR® Thunder™ 2004 Colin McRae™ Rally 4 Need For Speed™ Underground Corvette® Need For Speed™: Hot Pursuit 2 Driven Need for Speed™: Most Wanted Enthusia Professional Racing Need for Speed™: Underground 2 Evolution GT™ NHRA™ Championship Drag Racing™ F1™ 2001 Pro Race Driver F1™ 2002 R: Racing Evolution F1™ Career Challenge Rally Championship Ferrari® F355 Challenge™ Rally Fusion: Race of Champions Flatout™ Richard Burns Rally™ Ford Mustang: The Legend Lives RoadKill Formula One 2001™ Shox™ Formula One 2002™ Smuggler's Run 2: Hostile Territory Formula One 2003™ Starsky & Hutch™ Formula One 2004™ Street Racing Syndicate™ Gran Turismo™ 3 A-spec Test Drive® Gran Turismo™ 4 Test Drive® Eve of Destruction Gran Turismo™ Concept: 2001 Tokyo Test Drive® Off-Road: Wide Open™ Gran Turismo™ Concept: 2002 Tokyo-Geneva The Simpsons™ Hit & Run Grand Prix Challenge The Simpsons™ Road Rage Hot Wheels ™ Velocity X TOCA Race Driver™ 2 Initial D: Special Stage TOCA Race Driver™ 3 Juiced™ Total Immersion Racing™ Knight Rider™ Twisted Metal Black Online Lotus Challenge™ V-Rally™ 3 Midnight Club™ 3: DUB Edition World of Outlaws: Sprint Cars 2002 Midnight -

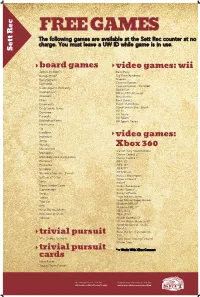

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

New Playstation®3 (Cechh00 Series) Comes in Two Color

NEW PLAYSTATION®3 (CECHH00 SERIES) COMES IN TWO COLOR VARIATIONS AT A NEW PRICE New PS3 with 40GB HDD to become available at 39,980 Yen on November 11th, 2007 Along With DUALSHOCK®3 at 5,500 Yen Tokyo, October 9, 2007 – Sony Computer Entertainment Japan (SCEJ), a division of Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. (SCEI) responsible for business operations in Japan, today announced that it would launch a new PLAYSTATION®3 (PS3™) model in Japan on November 11th at a recommended retail price of 39,980 yen (including tax). The new PS3 is equipped with a 40GB hard disk drive (HDD) and comes in two color variations of “Clear Black” and newly introduced “Ceramic White” to meet a variety of users’ lifestyle and preferences. Along with the introduction of the new model, the company also announced that effective October 17th, 20GB HDD and 60GB HDD models currently available in the market will have a recommended retail price of 44,980 yen and 54,980 yen (including tax) respectively. Moreover, DUALSHOCK®3 Wireless Controller which was revealed at Tokyo Game Show, will become available in the Japanese market on November 11th in two colors of “Black” and “Ceramic White” at a recommended retail price of 5,500 yen including tax. While holding the state-of-the-art technologies which define PS3 as an advanced platform to enjoy next generation interactive entertainment contents on Blu-ray Disc as well as via broadband network at home, new PS3 comes in the market at a highly attractive price. Reflecting both the increased efforts to improve software development environment and the availability of a more extensive line-up of PS3 specific titles, the new PS3 will no longer play PlayStation®2 titles. -

102413435.Pdf

NO 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272 273 274 275 276 277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288 289 290 291 292 293 294 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368 369 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 -

Titles Sep 29, 2021

All titles Sep 29, 2021 Name Description Rating Price Aggressive Inline Skating tricks with massive outdoor levels 77% Used £6.00 Freaky Flyers rare toony flyer 69% Used £10.00 Alias Its got gadgets! and girls! and thats about all 58% Used £10.00 Used £5.00 Full Spectrum Warrior Based on US army training. Best multi 80% America's Army: Rise of a Soldier 75% Used £7.50 No-Bk £4.00 Amped 2 80% No-Bk £4.00 Fuzion Frenzy 65% Used £6.00 Amped: Freestyle Snowboarding 79% Used £6.00 Galleon 71% Used £12.50 Armed and Dangerous 78% Used £8.50 Goblin Commander: Unleash the Horde Command & Conquor type game.. 73% Used £15.00 Bard's Tale The Excellent RPG. Coin & Cleavage is your goal. 73% Used £12.50 GoldenEye: Rogue Agent Intense 3D shooter - 100 weapon combos 62% Used £5.00 Batman Begins A 'dark' Batman game based on the movie 70% Used £10.00 Grabbed by the Ghoulies Jokey and spooky adventure 69% Used £12.50 Beyond Good & Evil Cartoony stealthy action game 88% Used £15.00 Gravity Games Bike: Street Vert Dirt 22% Used £6.00 Black Very nice FPS. 76% Used £12.50 Great Escape The Get out POW camp. Rush around adventure 57% Used £6.00 Blade II Falls short of the goretastic action of the movie 66% Used £12.50 Group S Challenge Street racer 53% Used £5.00 Blinx 2: Masters of Time & Space 72% Used £12.50 Gun Metal Control a 10m high robot fighter 69% Used £7.50 Blinx: The Time Sweeper 67% Used £10.00 Half-Life 2 87% Used £12.50 BloodRayne Dire vampire adventure yarn 74% Used £10.00 Used £7.50 Halo 2 The story continues in this classic 88% Brian Lara International Cricket 2005 Superb cricket game! 77% Used £7.50 No-Bk £5.00 Brothers in Arms: Road to Hill 30 Team Strategy based on D-Day 85% Used £5.00 Halo 2 Multiplayer Map Pack Requires Halo 2 - Play split-screen 85% Used £6.00 Brute Force Squad based shooter 77% Used £5.00 Halo: Combat Evolved THE pioneering Xbox game. -

Fifa 10 Free Download for Pc Full Version FIFA 21 Download

fifa 10 free download for pc full version FIFA 21 Download. Download FIFA 21 for free – learn how to enjoy the latest instalment of FIFA cycle! F IFA 21 is yet another part of very successful series that allowed us to delve into the virtual world of football. It is a discipline that brings almost everyone behind TV screens or stadiums. No wonder that most of us would like to play the game and feel the incredible emotions all the professional footballers feel. For this reason, we decided to create a very simple access to FIFA 21 download links . It is a great opportunity to test out recently released FIFA game. There are plenty of novelties and features that the authors decided to include, so it is definitely not the same game with another number. If you don’t believe, here is your chance to test it out! What makes FIFA 21 so interesting? Before we tell you more about our installing device and FIFA 21 download links, we should certainly take a closer look at the authors of this game as well as the basics. As we all know, FIFA 21 is yet another instalment that was created by Electronic Arts Sports (known as EA Sports). It is one of the most popular and the most profitable cycles that up to this moment sold in millions of copies. Another part of the game once again allows us to control our favorite club or a footballer . The game introduces several novelties. The most important changes regard the artificial intelligence as well as career game mode. -

Driving Academy Gevorderden.Pdf 2.42 Mb

GranTurismo5.nl Jilt GEVORDERDEN GEVORDERDEN Pagina 2 DISCLAIMER Deze driving academy is bedoeld voor het spel Gran Turismo 5 Prologue voor de Sony Playstation 3. Ondanks dat dit spel "real driving simulator" wordt genoemd, is Gran Turismo afwijkend van de werkelijkheid. Dit betekent dat deze driving academy niet bedoeld is voor gebruik op de openbare weg, tuning van auto's of andere zaken die van toepassing zouden kunnen zijn in de "echte wereld". ACADEMY Deze Academy is bedoeld voor iedere race fanaat die in het gelukkige bezit is van Gran Turismo 5 Prologue. Rijden met auto’s die voor velen in het dagelijkse leven financieel niet haalbaar zijn. Passie voor auto’s en racen met de authentieke motor geluiden en dito afstellingen. Deze academy moet je beter op weg kunnen helpen om echt harder te gaan in Gran Turismo 5 Prologue. De grenzen van jezelf, de auto waarin je rijdt en het circuit waar jij je op bevind, op te zoeken. De kunst is om het stapsgewijs uit te bouwen zodat je voor jezelf de fijnste auto’s en afstellingen kunt uitproberen. Veel lees en race plezier. www.GranTurismo5.nl GEVORDERDEN Pagina 3 Welkom als gevorderde! Hier gaan we het hebben over type aandrijving die we in de Gran Turismo 5 Prologue kennen (FWD, RWD, AWD), wat onderstuur en overstuur is en wat er mee of tegen kunnen doen, drafting / slipstreamen, bochten technieken, uitaccelereren en spiegelen. AANDRIJVING FWD Wat is het De Front Wheel Drive, of voorwiel aangedreven auto. In beginners al uitvoerig besproken. De voorwiel aandrijver is een auto met meestal de motor voorin en de aandrijving op de voorste wielen.