Copyright Chawton House Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blockade Runners: MS091

Elwin M. Eldridge Collection: Notebooks: Blockade Runners: MS091 Vessel Name Vessel Type Date Built A A. Bee Steamship A.B. Seger Steamship A.C. Gunnison Tug 1856 A.D. Vance Steamship 1862 A.H. Schultz Steamship 1850 A.J. Whitmore Towboat 1858 Abigail Steamship 1865 Ada Wilson Steamship 1865 Adela Steamship 1862 Adelaide Steamship Admiral Steamship Admiral Dupont Steamship 1847 Admiral Thatcher Steamship 1863 Agnes E. Fry Steamship 1864 Agnes Louise Steamship 1864 Agnes Mary Steamship 1864 Ailsa Ajax Steamship 1862 Alabama Steamship 1859 Albemarle Steamship Albion Steamship Alexander Oldham Steamship 1860 Alexandra Steamship Alfred Steamship 1864 Alfred Robb Steamship Alhambra Steamship 1865 Alice Steamship 1856 Alice Riggs Steamship 1862 Alice Vivian Steamship 1858 Alida Steamship 1956 Alliance Steamship 1857 Alonzo Steamship 1860 Alpha Steamship Amazon Steamship 1856 Amelia Steamship America Steamship Amy Steamship 1864 Anglia Steamship 1847 Anglo Norman Steamship Anglo Saxon Steamship Ann Steamship 1857 Anna (Flora) Steamship Anna J. Lyman Steamship 1862 Anne Steamship Annie Steamship 1864 Annie Childs Steamship 1860 Antona Steamship 1859 Antonica Steamship 1851 Arabian Steamship 1851 Arcadia Steamship Ariel Steamship Aries Steamship 1862 Arizona Steamship 1858 Armstrong Steamship 1864 Arrow Steamship 1863 Asia Steamship Atalanta Steamship Atlanta Steamship 1864 Atlantic Steamship Austin Steamship 1859 B Badger Steamship 1864 Bahama Steamship 1861 Baltic Steamship Banshee Steamship 1862 Barnett Steamship Barroso Steamship 1852 Bat Steamship -

The Newark Post

-...--., -- - ~ - -~. I The Newark Post PLANS DINNER PROGRAM oC ANDIDATES Newark Pitcher Twirls iFINED $200 ON ANGLERS' ASS'N No Hit, No-Run Game KIWANIS HOLDS FORP LACE ON Roland Jackson of t he Newark SECOND OFFENCE SEEKS INCREASE J uni or Hig h Schoo l baseball ANNUAL NIGHT team, ea rly in life realized t he SCHOOLBOARD I crowning ambition of every Drunken Driver Gets Heavy Newark Fishermen Will Take AT UNIVERSITY ',L baseball pitcher, when, Friday, Penalty On Second Convic- 50 New Members; Sunset S. GaJlaher Fil es For Re- I he pi tched a no-hit, no-run game against Hockessin, in the D. I. 300 Wilmington Club Mem election , !\ ll's. F. A. Wheel tion; Other T rafflc Cases Lake .Well Stocked A. A. Elementary League. To bers Have Banquet In Old ess Oppno's Him ; Election make it a real achievement, the ga me was as hard and cl ose a s Frank Eastburn was a rre ted, Mon The Newa rk Angler Association College; A. C . Wilkinson May 4. ewark Pupils Win a ba ll game can be that comes to day, by a New Cast le County Con held its first meeting of the year, last a decision in nine innings, for stabl e on a charge of dr iving while F riday night at the Farmer's Trust Arranges Program Newark won the game with a in toxicated. After hi s arrest he was Company. O. W. Widdoes, the presi lone run in the lucky seventh. taken before a physician and pro dent, presided. -

Dr. J. T. SALTER Rose & Ellsworth

B u c h a n a n R ecord, BIG BARGAINS . PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY, ----- EVT----- -iN - 7 0 H 1 T Gr- H O L M E S. TSRMS, S 1.50 PER YEAR eAXABCE IS ADVANCE. uiEencuiEs nits Kim si imam. VOLUME XXV. BUCHANAN, BEBPJEN COUNTY, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY. OCTOBER 29, 1891. NUMBER 40. OFFICE—IaRecorfl BuUding,OakStreet THE PESSIMISTIC MILLIONAIRE. that the quiet and silence seemed not Selfishness W ell Bewavded. Ask No Questions. unnatural. BT BROWNE I'liHIiOIAJs. The subject of the ethics of polite The old proverb to the effect that Business Directory. She opened the door and'went in. ness as manifested by travelers in those who ask no questions will be In Iho days when I was a growing boy, Ho one was there. The door into the yielding or retaining their car seats told no lies conveys a lesson that is I longed for man’s pow er and pleasure save, ticket office was open, hut the seat in SABBATU SERVICES. forms a never-ending topic of conver worth heeding. Even among the well- But now that I’ve reached that high estate, front of the desk was empty. sation among those who have occasion bred, questions are often asked which SERVICES are Reid, every Sabbath at 10:30 Long1 Goats & Cloaks. I ’d ju st like to bo a b oy onco m ore. Phyllis looked around in some per O o’ clock A. a ., at the Church o f the “ Larger to study the various phases of the it is irksome or inexpedient, to answer. -

Dwight D. Eisenhower Stereo Slide Collection

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER STEREO SLIDE COLLECTION Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum Audiovisual Collection Because of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s interest in stereographic photography, the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum holds a large collection of stereo slides. The majority of the 1,154 slides were taken during the years 1948-1958 by Eisenhower and members of his staff using a Realist Stereo Camera made by the David White Company, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The collection documents events from his personal life as well as major news events. Slides relate to the personal interests, family, and social life of Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower as well as friends and acquaintances. There are slides of friends, members of their staff and business associates, either appearing alone or as a group with the Eisenhower’s. Other slides taken during official SHAPE trips include scenic views as well as official functions, and military inspections. There are slides of places and scenes, primarily scenic in nature, including views of Camp David, Maryland; Abilene, Kansas; and the Augusta National Golf Course. Slides taken of historic events include coverage of the 1952 Presidential Campaign, the 1953 Inauguration, as well as international events such as the 1953 Bermuda Conference and the funeral of King George VI in 1952. 1 STEREO SLIDES 71-856-1--23 Lipson, Portugal, January 1959 (23) 71-857-1--7 Luxemburg, January 19, 1951, Pearl Mesta’s Residence (3) Luxemburg, January 19, 1951, Hotel Alfa (4) 71-858-1 Pad Hambourg, Germany, January -

51ST ANNUAL CONVENTION March 5–8, 2020 Boston, MA

Northeast Modern Language Association 51ST ANNUAL CONVENTION March 5–8, 2020 Boston, MA Local Host: Boston University Administrative Sponsor: University at Buffalo SUNY 1 BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Carole Salmon | University of Massachusetts Lowell First Vice President Brandi So | Department of Online Learning, Touro College and University System Second Vice President Bernadette Wegenstein | Johns Hopkins University Past President Simona Wright | The College of New Jersey American and Anglophone Studies Director Benjamin Railton | Fitchburg State University British and Anglophone Studies Director Elaine Savory | The New School Comparative Literature Director Katherine Sugg | Central Connecticut State University Creative Writing, Publishing, and Editing Director Abby Bardi | Prince George’s Community College Cultural Studies and Media Studies Director Maria Matz | University of Massachusetts Lowell French and Francophone Studies Director Olivier Le Blond | University of North Georgia German Studies Director Alexander Pichugin | Rutgers, State University of New Jersey Italian Studies Director Emanuela Pecchioli | University at Buffalo, SUNY Pedagogy and Professionalism Director Maria Plochocki | City University of New York Spanish and Portuguese Studies Director Victoria L. Ketz | La Salle University CAITY Caucus President and Representative Francisco Delgado | Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY Diversity Caucus Representative Susmita Roye | Delaware State University Graduate Student Caucus Representative Christian Ylagan | University -

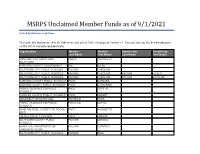

MSRPS Unclaimed Member Funds As of 4/30/2021

MSRPS Unclaimed Member Funds as of 9/1/2021 Sorted by Member Last Name To search this document, click the Edit menu and select Find, or just press Control + F. You can also use the Bookmarks pane on the left to navigate alphabetically. Organization Member Member Beneficiary Beneficiary Last Name First Name Last Name First Name UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND PABLA TARUNJEET BALTIMORE HARFORD COUNTY GOVERNMENT PAC ELLEN BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA PACANA ELISEO BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA PACANA ELIZALDE HARFORD COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE BARBARA HOWARD COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE CATHERINE PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PACE CRYSTAL SCHOOLS CHARLES COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE ROBERT UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND PACHECO ELVIA PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PACHECO MAYRA SCHOOLS ANNE ARUNDEL CO DEPT OF SOCIAL PACK ANJENETTE SERV TALBOT COUNTY COUNCIL PACK LANARD BALTIMORE COUNTY PUBLIC PACKER AMANDA SCHOOLS MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF PACKER KIMBERLY TRANSPORTATION BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PADDER IRAM Organization Member Member Beneficiary Beneficiary Last Name First Name Last Name First Name PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADDOCK JACK SCHOOLS PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADDOCK JACK PADDOCK LANDON SCHOOLS ANNE ARUNDEL CO PUBLIC SCHOOLS PADDY GLADYS PADDY CYNTHIA WESTERN MARYLAND HOSPITAL PADEN GLENNA PADEN HAROLD CENTER PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADEN JENNIFER SCHOOLS WASHINGTON COUNTY PUBLIC PADEN JULIAN PADEN MARY SCHOOLS TOWN OF CHEVERLY PADGETT MATTHEW HARFORD COUNTY GOVERNMENT PADGETT TIFFANY -

The Evolution of Yeats's Dance Imagery

THE EVOLUTION OF YEATS’S DANCE IMAGERY: THE BODY, GENDER, AND NATIONALISM Deng-Huei Lee, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2003 APPROVED: David Holdeman, Major Professor Peter Shillingsburg, Committee Member Scott Simpkins, Committee Member Brenda Sims, Chair of Graduate Studies in English James Tanner, Chair of the Department of English C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Lee, Deng-Huei, The Evolution of Yeats’s Dance Imagery: The Body, Gender, and Nationalism. Doctor of Philosophy (British Literature), August 2003, 168 pp., 6 illustrations, 147 titles. Tracing the development of his dance imagery, this dissertation argues that Yeats’s collaborations with various early modern dancers influenced his conceptions of the body, gender, and Irish nationalism. The critical tendency to read Yeats’s dance emblems in light of symbolist- decadent portrayals of Salome has led to exaggerated charges of misogyny, and to neglect of these emblems’ relationship to the poet’s nationalism. Drawing on body criticism, dance theory, and postcolonialism, this project rereads the politics that underpin Yeats’s idea of the dance, calling attention to its evolution and to the heterogeneity of its manifestations in both written texts and dramatic performances. While the dancer of Yeats’s texts follow the dictates of male-authored scripts, those in actual performances of his works acquired more agency by shaping choreography. In addition to working directly with Michio Ito and Ninette de Valois, Yeats indirectly collaborated with such trailblazers of early modern dance as Loie Fuller, Isadora Duncan, Maud Allan, and Ruth St. -

Ballet and Modern Dance in the Construction of Modern México (1919-1940): an Overview 9

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Choreographing Politics, Dancing Modernity: Ballet and Modern Dance in the Construction of Modern México (1919-1940) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Jose Luis Reynoso 2012 © Copyright by Jose Luis Reynoso 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Choreographing Politics, Dancing Modernity: Ballet and Modern Dance in the Construction of Modern México (1919-1940) by Jose Luis Reynoso Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair In this dissertation, I analyze the pivotal role that ballet and modern dance played in the construction of modern México during the development of its post-revolutionary history and culture from 1919 to 1940. In this doctoral research, I approach dance as a means of knowledge production that contributes to shaping the cultural contexts in which individual and collective identities are produced while perpetuating systems of sociopolitical and economic domination and/or offering alternatives to restructure unequal power relations. As an organizing principle, this dissertation presupposes that dances always enact, explicitly and/or implicitly, sets of political assumptions that affect the bodies that participate by dancing or by watching dance. In other words, I examine how dance represents race, class, gender, and sexuality; how corporeal ii difference is arranged in space; what does the dance say about human relations; and how subjectivity is constructed through dance training and performing on stage. I also consider whose worldview, values and interests are enacted on stage and thereby normalized beyond the stage. -

(LAC) Title 33, Part IX, Chapter 11

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. September 7, 2021 Louisiana Administrative Code (LAC) Title 33, Part IX. Water Quality Chapter 11. Surface Water Quality Standards Effective August 10, 2021 The following provisions are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes with the exception of the provisions described below. - Seasonal dissolved oxygen (DO) criteria for waters in the Lake Pontchartrain Basin (eastern Lower Miss River Alluvial Plain ecoregion) were vacated by court order number 18-1632 on February 25, 2019 and are not in effect for CWA purposes. Affected criteria appear in strikeout. Title 33, Part IX Chapter 11. Surface Water Quality §1105. Definitions Standards Acute Toxicity―any lethal or deleterious effect on representative sensitive organisms that results from a single §1101. Introduction dose or exposure of a chemical or mixture of chemicals within A. The purpose of this Chapter is to establish surface a short period of time, usually less than 96 hours. water quality standards that will: Administrative Authority―the Secretary of the Department of Environmental Quality, or his designee or the appropriate 1. provide for the protection and preservation of the assistant secretary or his designee. abundant natural resources of Louisiana's many and varied aquatic ecosystems; Ambient Toxicity―the effect measured by a toxicity test on a sample collected from a water body. -

Naval Force Shells Inchon As Signs of Chinese

LIGHTINGUP TIME 6.17 pain. Yesterday's Weather Maximum temperature 71.5 Minimum temperature '. 65.5 Sunshine 7J hours Tide Table Fer January Rainfall 18 inches Date High Water Low Water Sun- Sun- A.M. P.M. A.M. P.M. rise set 26 10=39 11.59 4.22 5.00 7.19 5 47 27 11.18 1144 5.07 5.36 7.18 5.48 ffilj.* VOL 31 — NO. 22. HAMILTON, BERMUDA FRIDAY, JANUARY 26, 1951 6D PER COPY Fate Of Britain's "Z" Men Undecided Naval Force Shells Inchon As Signs LONDON, Jan. 25 (Reuter). — One other important topic be Commons on Monday. Deputy The Cabinet is expected to make lieved discussed by the Cabinet Prime Minister Morrison made a definite statement on Britain's today was the future of Britain's the announcement today after the rearmament and military call-up 4,000,000 "Z" men — reservists Cabinet had met to study the plans before General Eisenhower who fought in the Second World effects of the expanded pro reports to Congress next Thursday War. gramme on the national economy Of Chinese 'Withdrawal" Multiply on the state of the Atlantic The Government has indicated and to discuss how far to go in nation's defences, observers here it intends to call up the "_." men calling up reserves for the forces. .aid today. for training. But it has not stated The Cabinet met again in the TOKYO, Jan. 25 (Reuter). — A Tbey said General Eisenhower how many it wiU mobilize or evening but final decisions prob United Nations naval force tonight should be familiar with Britain's when they will be called up. -

“It Would Just Kill Me to Marry Mary Todd”: Courtship and Marriage

Chapter Six “It Would Just Kill Me to Marry Mary Todd”: Courtship and Marriage (1840-1842) In 1842, Lincoln married Mary Todd, a woman who was to make his domestic life “a burning, scorching hell,” as “terrible as death and as gloomy as the grave,” according to one who knew him well.1 COURTING MARY OWENS Lincoln’s courtship of Mary Todd is poorly documented, but indirect light on it is shed by his earlier, well-documented romance with Mary S. Owens. Born in Kentucky a few months before Lincoln, Mary Owens received a good education at the home of her wealthy father, a planter in Green County.2 She “was very different from Anne Rutledge.” Not only was she older, bigger, better-educated, and raised “in the most refined society,” she also “dressed much finer than any of the ladies who lived about New 1 William H. Herndon, quoted in Michael Burlingame, The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 268. 2 Nathaniel Owens, out “of his deep concern for the education of his children . maintained a private school in his pretentious plantation home, to which came instructors from Transylvania University, Ky., to give instruction to his children and those of his neighbors.” On his 5000-acre plantation he grew cotton and tobacco, which he farmed with the help of two dozen slaves. Notes on Nathaniel Owens, Fern Nance Pond Papers, Menard County Historical Museum, Petersburg, Illinois. According to William B. Allen, Owens “was a farmer of good education for the times, and of a high order of native intellect. -

Emerging Agency in American Women's Novels Before the Civil War

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2013 From Sinners to Saints: Emerging Agency in American Women's Novels before the Civil War Amy Howard Green West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Green, Amy Howard, "From Sinners to Saints: Emerging Agency in American Women's Novels before the Civil War" (2013). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4969. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4969 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Sinners to Saints: Emerging Agency in American Women's Novels before the Civil War Amy Howard Green Dissertation submitted to The Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Timothy Sweet, Ph.D., Chair Cari Carpenter, Ph.D. Michael Germana, Ph.D. John Ernest, Ph.D. Janie Hinds, Ph.D.