Laura Olson Osterman Associate Professor University of Colorado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigation Map of Bulgaria Including Offroadmap by Offroad-Bulgaria.Com Version 2021 Q1

Navigation Map of Bulgaria Including OFFRoadMap by OFFRoad-Bulgaria.com Version 2021 Q2 The purpose of this map is to provide accessible, accurate and up-to-date information for your GPS devices. Despite all efforts made by the creators to achieve this goal, the roads and the data included in this digital map are intended to be used as guidance only and should not be used solely for navigation. The creators of this map make no warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of the map data. In no event will the creators of this map be liable for any damages whatsoever, including but not limited to loss of revenue or profit, lost or damaged data, and expenses, arising in any way from or consequential upon the use of, or the inability to use this digital map. Contents: - Registering your map - Usage details - OFRM Geotrade 2021 Q2 variants - Coverage >>>>> REGISTRATION <<<<< To register your OFRM Geotrade map, please visit out website www.karta.bg. Click on “Create profile” in the top right corner of the screen and create your personal account. When done, the Support page will load automatically. Click on the button “Register OFRM Geotrade” and enter the 25-symbol map serial number and GPS model to activate your map’s update subscription (if your map includes one). To obtain the 25-symbol serial number, connect your GPS device to your computer via USB cable. If you have a GPS device with preloaded OFRM map, you will find the serial number in file “serial.txt” in the root folder of your device’s base memory or in the file “gmapsupp.unl” in folder “Garmin” (or folder “Map” on the newer models of the nüvi series and the new Drive series) of your device’s base memory. -

Bulgaria Revealed.Pages

Licensed under Velvet Tours 1 Spiridon Matei St. 032087 Bucharest, Romania Tour operator license #6617 Bulgaria revealed (10 nights) Tour Description: "Bulgaria Revealed" allows you to experience an extensive array of carefully-chosen Bulgarian cultural landmarks via a comprehensive, yet relaxed itinerary. Begin in Sofia, where you’ll stroll along the famed yellow brick road to view the capital’s major sights. Continue on to Boyana Church and the spectacular Rila Monastery before traveling to Melnik, surrounded by unusual sand formations and situated right in the heart of Bulgarian wine country. Next, tour Rozhen Monastery before stopping off in the exquisite town of Kovacevica. Take in the breathtaking natural scenery at Dospat Lake and Trigrad Gorge, then explore the mysterious Yagodinska Cave. In Batak, visit a key site in the 1876 April Uprising; in the village of Kostandovo, tour the workshop of a master traditional carpet-maker. Experience an evening walking tour in Plovdiv, then admire the abundance of traditional architecture in Koprivshtitsa. At Starosel, investigate the largest Thracian burial complex in Bulgaria. Visit the Thracian Tomb at Kazanlak, drive through the stunning Shipka Pass, and tour the incredible outdoor cultural museum at Etara. Witness the woodcarving tradition at Tryavna, shop for crafts in Veliko Tarnovo, and stroll through the architectural gem of Arbanassi. View the Madara Horseman as well as the exquisite sites at Ivanovo and Sveshtari. See the world’s oldest gold treasure at Varna, with the option to tour Balchik Palace and the Aladzha Cave Monastery—or simply spend the afternoon on the beach. Finally, enjoy a splendid day on the magnificent peninsula of Nessebar before returning to Sofia and your flight home. -

PROFESSIONAL PROFILE Arch. Yordan Todorov Ulyanov

PROFESSIONAL PROFILE arch. Yordan Todorov Ulyanov Address: Sofia, Mladost - 1, block 98, entrance V, floor 7, аp. 46 Phone: (+359) 0889233722 E-mail: [email protected] Date of birth: 12.03.1983г., Sofia Nationality: Bulgarian Marital status: Married with two kids Education: Master degree in Architecture Name of school Date from (month/year) - to (month/ year) Obtained qualifications or diplomas: from 10.2001 to 02.2007 Master degree University if Architecture, Civil Engineering Serial number: UACG-99, № 011524, and Geodesy, Sofia, Faculty of Architecture Registration № 35684 from 2007, ARCHITECT to 24.05.2001 Diploma of Secondary Education PMG “Nancho Popovich”, Shumen, Serial number А-01, № 2151023 profiled class with intensive math, computer Registration № 529 / 28.06.2001 science and English training Languages: (level of language proficiency from 1 to 5, 1- best, 5 – worst) Language Reading Speaking Writing English 1 1 1 German 4 4 4 Membership in professional associations: The Chamber of Architects in Bulgaria Additional qualifications: Arch. Yordan Ulyanov is certified by the “Passive House Institute”, Darmstadt, Germany passive house designer - CERTIFIED PASSIVE HOUSE DESIGNER. Other skills: · Computer skills: - ArchiCAD, 2D and 3D; - ArtLantis Studio for 3D rendering; - PhotoShop, CorelDraw; - High level proficiency in Windows, MS Office. · Artistical skills: - concept development; - drawing and modeling; Current employment: “Ulyanov Architects” Ltd. – Senior architect, lead designer and project manager Work experience in current employment: 14.09.2010 - present Employment History: Date: City Employer Position Job description/ from (month/year) - Responsibilities to (month/year) from 01.03.2007 – to Sofia “Atelier Karadjov” architect Designing concept 14.09.2010 Ltd., and technical Sofia projects. -

Identity, Nationalism, and Cultural Heritage Under Siege Balkan Studies Library

Identity, Nationalism, and Cultural Heritage under Siege Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović (University College London) Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos (Columbia University) Alex Drace-Francis (University of Amsterdam) Jasna Dragović-Soso (Goldsmiths, University of London) Christian Voss, (Humboldt University, Berlin) Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic (University of Munich) Lenard J. Cohen (Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup (Columbia University) Robert M. Hayden (University of Pittsburgh) Robert Hodel (Hamburg University) Anna Krasteva (New Bulgarian University) Galin Tihanov (Queen Mary, University of London) Maria Todorova (University of Illinois) Andrew Wachtel (Northwestern University) VOLUME 14 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Identity, Nationalism, and Cultural Heritage under Siege Five Narratives of Pomak Heritage—From Forced Renaming to Weddings By Fatme Myuhtar-May LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Pomak bride in traditional attire. Ribnovo, Rhodope Mountains, Bulgaria. Photo courtesy Kimile Ulanova of Ribnovo. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Myuhtar-May, Fatme. Cultural heritage under siege : five narratives of Pomak heritage : from forced renaming to weddings / by Fatme Myuhtar-May. pages cm. — (Balkan studies library, ISSN 1877-6272 ; volume 14) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-27207-1 (hardback : acid-free paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-27208-8 (e-book) 1. Pomaks—Bulgaria—Social conditions. 2. Pomaks—Bulgaria—Social life and customs. 3. Pomaks— Bulgaria—Case studies. 4. Pomaks—Bulgaria—Biography. 5. Culture conflict—Bulgaria. 6. Culture conflict—Rhodope Mountains Region. 7. Bulgaria—Ethnic relations. 8. Rhodope Mountains Region— Ethnic relations. I. Title. DR64.2.P66M98 2014 305.6’970499—dc23 2014006975 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual ‘Brill’ typeface. -

Demografija-8.Pdf

ДЕМОГРАФИЈА, књ. VIII, 2011. DEMOGRAPHY vol. VIII 2011 UDK 314.116-022.527(100)”200/...”; 314.113(497.11) ”199/...” Прегледни чланак Review article Милена Спасовски Даница Шантић СЕДАМ МИЛИЈАРДИТИ СТАНОВНИК СВЕТА – ПОЛАРИЗОВАНОСТ ДЕМОГРАФСКОГ РАЗВИТКА НА ∗∗∗ ПОЧЕТКУ XXI ВЕКА Извод: Поводом рођења седам милијардитог становника света скреће се пажња на дивергентне демографске трендове у националним, регионалним и континентал- ним оквирима. Они се манифестују кроз проширену природну репродукцију и по- пулациону експанзију у Африци, Латинској Америци и Азији, са једне и депопу- лацију и старење становништва у Европи, Северној Америци и Аустралији са дру- ге стране. Повећање броја становника света за 1 милијарду дешава се у току једне деценије, што има бројне репрекусије на стање и заштиту животне средине, иско- рењивање глади и сиромаштва, политичких напетости и сукоба, односно опстанка будућих генерација. Србија се данас налази међу земљама које се суочавају са смањењем популације и страхом од изумирања. Кључне речи: становништво, демографски трендови, Србија, природне компо- ненте, миграције. Abstrac t: THe birtH of seven billiontH citizen of tHe world draws attention to tHe divergent demograpHic trends in national, regional and continental level. THose trends are evident tHrougH extensive natural reproduction and population expansion in Africa, Latin America and Asia, and tHrougH depopulation and population aging in Europe, NortH America and Australia. World population number is increasing for 1 billion almost everY decade, wHicH Has numerous repercussions on tHe environment, eradicating Hunger and povertY, political tensions and conflicts, and survival of future generations. Serbia is todaY among tHe countries facing a population decline and fear of population extinction. Key worDs: population, demograpHic trends, Republic of Serbia, natural increase, migrations Увод Уједињене Нације су 31. -

Priority Public Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste

Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Develonment Europe and Central Asia Region 32051 BULGARIA Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL SEQUENCING STRATEGIES FOR EU ACCESSION PriorityPublic Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste *t~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Public Disclosure Authorized IC- - ; s - o Fk - L - -. Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized May 2004 - "Wo BULGARIA ENVIRONMENTAL SEQUENCING STRATEGIES FOR EU ACCESSION Priority Public Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste May 2004 Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Europe and Central Asia Region Report No. 27770 - BUL Thefindings, interpretationsand conclusions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Coverphoto is kindly provided by the external communication office of the World Bank County Office in Bulgaria. The report is printed on 30% post consumer recycledpaper. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................... i Abbreviations and Acronyms ..................................................................... ii Summary ..................................................................... iiM Introduction.iii Wastewater.iv InstitutionalIssues .xvi Recommendations........... xvii Introduction ...................................................................... 1 Part I: The Strategic Settings for -

Agriculture & Food ISSN 1314-8591, Volume 8, 2020 Journal Of

Agriculture & Food Journal of International Scientific Publications ISSN 1314-8591, Volume 8, 2020 www.scientific-publications.net CONSERVING LOCAL DIVERSITY OF COMMON BEAN (PHASEOLUS VULGARIS L.) IN SITU / ON FARM T. Stoilova*, P. Chavdarov, N. Velcheva Institute of Plant Genetic Resources, 2 Drugba str., Sadovo 4122, Bulgaria Abstract Dry bean is considered as one of the major legume crop with big number of landraces grown in Bulgaria. Local forms of Phaseolus spp. are conserved on farm in different geographical regions and show a wide morphological diversity. The aim of our study was to collect, conserve and characterize local populations of Phaseolus vulgaris L. and Phaseolus coccineus L. typically grown in Smilyan, Troyan and Velingrad regions. The most popular local forms were characterized using different approaches. In this paper we will present results from morphological characterization and phythopathological evaluation. Qualitative and quantitative traits were assessed on 50 accessions of Phaseolus spp. during vegetation cycle. All information was documented in European electronic catalog “EURISCO” and is available on line (http://eurisco.ecpgr.org) Key words: diversity, common bean, landraces, conservation 1. INTRODUCTION The grain legumes are important source of protein against to hunger and malnutrition in the world [1]. They supply 18-20% of total fund of plant protein. The seeds are 2 to 5 richest of proteins comparing with cereals, and most of them consist between 20-35% crude proteins [2]. Traditional food for Bulgarians is field beans (Phaseolus spp.). The common bean (Ph. vulgaris L.) is more popular in the country, while runner bean (Ph. coccineus L.) is adapted and well grown in the mountain regions. -

Microsoft Word

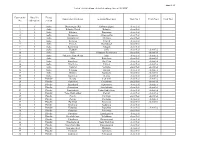

Health Promotion & Preventive Maternal and Child Health Care EuropeAid/122909/D/SER/BG Consortium led by Open Society Institute- Sofia Annex І – Monthly Progress Report – October 2008 V FINAL PROGRESS REPORT SEPTEMBER 2007 – NOVEMBER 2008 MONTHLY PROGRESS REPORT Reporting period 1-31 October 2008 During the reporting period – 1 – 31October 2008, the Consultant worked on the implementation of the following activities planned: Implementation of the primary health program for disadvantaged ethnic minority women and children – start of the preventive medical examinations The statistics for October 2008 show that the following examinations were conducted in the four project regions: October 2008 Region/period Pediatric OG Pap smears Total number of examinations examinations taken examinations Yambol (01.10- 330 330 210 660 25.10.2008) Dobrich (01.10- 682 579 579 626 28.10.2008 г.) Montana (01- 460 430 176 890 31.10.2008) Pazardjik 640 378 351 1018 (01-31.10.2008) Total 2112 1717 1316 3194 In October 2008 all mobile teams continued conducting the preventive examinations at places. In all four project regions the interest towards the examinations is growing. We present specific numbers, information and conclusions for each region: 1 Yambol region In October the OG and pediatric mobile units started visits in locations within the municipalities of Elhovo and Bolyarovo. The OG and pediatric examinations were conducted in accordance with the following schedule in the following locations: Date Location 01.10.2008 Straldzha 02.10.2008 Irechekovo 03.10.2008 Yambol, Kozarevo village 06.10.2008 Kozarevo village 07.10.2008 Straldzha 08.10.2008 Okop village 09.10.2008 Lozenets village 10.10.2008 Boyanovo 13.10.2008 Drazhevo village 14.10.2008 Straldzha, Zimnitsa 15.10.2008 Boyanovo village 16.10.2008 Zimnitsa village 17.10.2008 Malomirovo village 20.10.2008 Mamarchevo, Voden 24.10.2008 Yambol 25.10.2008 Straldzha To support the organization of preventive examinations in new locations, the following meetings were held: • 03.10.2008 г. -

Annex 14 Consecutive No No of the Railway Line Energy Section from Station/Block Post to Station/Block Post Track No 1 Track No

Annex 14 List of electrified/non-electrified railway lines of SE NRIC Consecutive No of the Energy from station/block post to station/block post Track No 1 Track No 2 Track No 3 No railway line section 1 1 Sofia Dimitrovgrad RS Kalotina Zapad electrified 2 1 Sofia Kalotina Zapad Kalotina electrified 3 1 Sofia Kalotina Dragoman electrified 4 1 Sofia Dragoman Aldomirovtsi electrified 5 1 Sofia Aldomirovtsi Slivnitsa electrified 6 1 Sofia Slivnitsa Petarch electrified 7 1 Sofia Petarch Kostinbrod electrified 8 1 Sofia Kostinbrod Voluyak electrified 9 1 Sofia Voluyak Sofia electrified electrified 10 1 Sofia Sofia Poduyane Patnicheska electrified electrified 11 1 Sofia Poduyane Patnicheska Iskar electrified electrified 12 1 Sofia Iskar Kazichene electrified electrified 13 1 Sofia Kazichene Elin Pelin electrified electrified 14 1 Sofia Elin Pelin Vakarel electrified electrified 15 1 Sofia Vakarel Verinsko electrified electrified 16 1 Sofia Verinsko Ihtiman electrified electrified 17 1 Sofia Ihtiman Kostenets electrified electrified 18 1 Sofia Kostenets Belovo electrified electrified 19 1 Plovdiv Belovo Septemvri electrified electrified 20 1 Plovdiv Septemvri Pazardzhik electrified electrified 21 1 Plovdiv Pazardzhik Ognyanovo electrified electrified 22 1 Plovdiv Ognyanovo Stamboliyski electrified electrified 23 1 Plovdiv Stamboliyski Todor Kableshkov electrified electrified 24 1 Plovdiv Todor Kableshkov Plovdiv electrified electrified 25 1 Plovdiv Plovdiv Por Iztok electrified electrified 26 1 Plovdiv Plovdiv Por Iztok electrified electrified -

RESULTS ANALYSIS from Survey for the Level of Awareness And

RESULTS ANALYSIS from survey for the level of awareness and knowledge of EU policies, and in particular the work of the EP in areas of importance to citizens, the political nature of the EP and the upcoming European Parliament elections in 2019 Contracting authority: Bratstvo 1869 Community Centre, Kyustendil Executor: Orlin Balabanov Date of preparation of the analysis: 27.02.2018 Kyustendil, 2018 I. INTRODUCTION The analysis of the results of a survey on the level of awareness and knowledge of EU policies, and in particular the work of the EP in areas of relevance to the citizens, the political nature of the EP and the upcoming 2019 European elections have been prepared under the project "Europe is hears your voice - BE ACTIVE!", Contract № COMM/SUBV/2017/E/0003, co-funded by the EP and Bratstvo 1869 Community Centre Kyustendil. Period of implementation: 01.01.2018 – 30.06.2018 Principal objective: The main objective of the project is to raise citizens' awareness of one of the main institutions of the EU - the European Parliament, showing its role not only in promoting democratic decision-making in Europe but also in supporting the struggle for democracy, freedom of speech and expression and fair elections all over the world. Specific objective: - to promote and multiply among the citizens of South-West Bulgaria / Kyustendil region and Blagoevgrad region a better understanding of the identity, role and political nature of the EP as the only democratically elected EU institution, by organizing information campaigns in different towns -

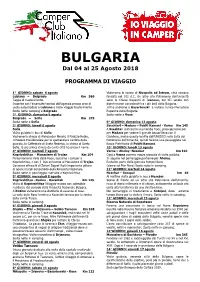

Programma Bulgaria

BULGARIA Dal 04 al 25 Agosto 2018 PROGRAMMA DI VIAGGIO 1° GIORNO: sabato 4 agosto Visiteremo le rovine di Nicopolis ad Istrum, città romana Lubiana – Belgrado Km 560 fondata nel 102 d.C. Un altro sito Patrimonio dell’Umanità Tappa di trasferimento. sono le Chiese Rupestri di Ivanovo, del XII secolo con Incontro con l’incaricato tecnico dell’agenzia presso area di dipinti murari considerati tra i più belli della Bulgaria. sosta autostradale a Lubiana e inizio viaggio trasferimento Infine andremo a Basarbovski a visitare l’unico Monastero Sosta notte camping a Belgrado. Rupestre della Bulgaria. 2° GIORNO: domenica 5 agosto Sosta notte a Ruse. Belgrado – Sofia Km 375 Sosta notte a Sofia. 9° GIORNO: domenica 12 agosto 3° GIORNO: lunedì 6 agosto Sveshtari – Madara – Pobiti Kamani - Varna Km 245 Sofia A Sveshtari visiteremo una tomba trace, proseguiremo poi Visita guidata in bus di Sofia. per Madara per vedere il grande bassorilievo con il Vedremo la chiesa di Aleksander Nevski, il Palazzo Reale, Cavaliere, anche questo iscritto dall’UNESCO nella Lista del Il Palazzo Presidenziale per lo spettacolare cambio della Patrimonio dell’Umanità, quindi faremo una passeggiata nel guardia, la Cattedrale di Sveta Nedelya, la chiesa di Sveta Bosco Pietrificato di Pobiti Kamani. Sofia, la più antica chiesa da cui la città ha preso il nome. 10° GIORNO: lunedì 13 agosto 4° GIORNO: martedì 7 agosto Varna – Aheloy -Nesebar km 103 Koprivshtitsa - Monastero di Trojan Km 104 Oggi a Varna avremo mezza giornata di visita guidata. Percorriamo la Valle delle Rose, lasciamo i camper a In seguito nel pomeriggio partiamo per Aheloy. -

SUPPORTING REPORT C Water Quality

SUPPORTING REPORT C Water Quality The Study on Integrated Water Management Final Report in the Republic of Bulgaria Supporting Report C Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................. i List of Tables ................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ................................................................................................................. iii List of Annexes ............................................................................................................... iv C WATER QUALITY ........................................................................................... C-1 C.1 General ............................................................................................................... C-1 C.2 Current Conditions of Water Quality ................................................................. C-1 C.2.1 Existing Water Quality Monitoring Networks ...................................... C-1 C.2.2 Water Quality Conditions ..................................................................... C-3 C.3 Current Conditions of Water Quality ................................................................. C-7 C.3.1 Existing Urban and Municipal wastewater Treatment Plants ............... C-7 C.3.2 National Program for Constructing WWTPs ........................................ C-7 C.4 Water Quality Management Plan ......................................................................