Transcript(PDF 211.40

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Nationals Released a Plan

COVID-19 RESPONSE May 2020 michaelobrien.com.au COVID-19 RESPONSE Dear fellow Victorians, By working with the State and Federal Governments, we have all achieved an extraordinary outcome in supressing COVID-19 that makes Victoria – and Australia - the envy of the world. We appreciate everyone who has contributed to this achievement, especially our essential workers. You have our sincere thanks. This achievement, however, has come at a significant cost to our local economy, our community and to our way of life. With COVID-19 now apparently under a measure of control, it is urgent that the Andrews Labor Government puts in place a clear plan that enables us to take back our Michael O’Brien MP lives and rebuild our local communities. Liberal Leader Many hard lessons have been learnt from the virus outbreak; we now need to take action to deal with these shortcomings, such as our relative lack of local manufacturing capacity. The Liberals and Nationals have worked constructively during the virus pandemic to provide positive suggestions, and to hold the Andrews Government to account for its actions. In that same constructive manner we have prepared this Plan: our positive suggestions about what we believe should be the key priorities for the Government in the recovery phase. This is not a plan for the next election; Victorians can’t afford to wait that long. This is our Plan for immediate action by the Andrews Labor Government so that Victoria can rebuild from the damage done by COVID-19 to our jobs, our communities and our lives. These suggestions are necessarily bold and ambitious, because we don’t believe that business as usual is going to be enough to secure our recovery. -

2010 Victorian State Election Summary of Results

2010 VICTORIAN STATE ELECTION 27 November 2010 SUMMARY OF RESULTS Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Legislative Assembly Results Summary of Results.......................................................................................... 3 Detailed Results by District ............................................................................... 8 Summary of Two-Party Preferred Result ........................................................ 24 Regional Summaries....................................................................................... 30 By-elections and Casual Vacancies ................................................................ 34 Legislative Council Results Summary of Results........................................................................................ 35 Incidence of Ticket Voting ............................................................................... 38 Eastern Metropolitan Region .......................................................................... 39 Eastern Victoria Region.................................................................................. 42 Northern Metropolitan Region ........................................................................ 44 Northern Victoria Region ................................................................................ 48 South Eastern Metropolitan Region ............................................................... 51 Southern Metropolitan Region ....................................................................... -

For VFBV District Councils

For VFBV District Councils This list shows responses from Victorian State MPs to VFBV’s 11 June letter on the issue of presumptive legislation – the firefighters’ cancer law that would simplify the path to cancer compensation for Victorian volunteer and career firefighters. District Councils are encouraged to use this list as part of their planning to ensure that volunteers contact all State MPs in their area and seek their support on this important issue. See the VFBV website for more information on the issue, including a copy of our ‘Notes for MPs’ that volunteers can present to MPs. As at 22 August 2013; There has been strong support from the Greens, who have presented draft legislation to State Parliament, and in-principle support from Labor The Coalition Government has not committed to supporting presumptive legislation. VFBV is committed to working with all Victorian MPs to secure all-party support for fairer and simpler access to cancer compensation for Victorian volunteer and career firefighters and a part of that is having volunteers talk to their local MPs. See below for the response received from individual MPs, listed in alphabetical order. Please advise the VFBV office of any contacts made and responses from MPs. Name, Party and Electorate Have they replied to VFBV’s Summary of the MPs’ advice or actions letter of 11 June 2013? Jacinta Allan No Supportive: Yes. Labor Bendigo East Shadow Minister for Emergency Services Jacinta Allan issued a media release on 6 February 2013, calling for the State Government to take part in round table discussions and stating that Labor supports the principal of presumptive legislation and wants to work with all parties on progressing this Bill through Parliament. -

Victoria New South Wales

Victoria Legislative Assembly – January Birthdays: - Ann Barker - Oakleigh - Colin Brooks – Bundoora - Judith Graley – Narre Warren South - Hon. Rob Hulls – Niddrie - Sharon Knight – Ballarat West - Tim McCurdy – Murray Vale - Elizabeth Miller – Bentleigh - Tim Pallas – Tarneit - Hon Bronwyn Pike – Melbourne - Robin Scott – Preston - Hon. Peter Walsh – Swan Hill Legislative Council - January Birthdays: - Candy Broad – Sunbury - Jenny Mikakos – Reservoir - Brian Lennox - Doncaster - Hon. Martin Pakula – Yarraville - Gayle Tierney – Geelong New South Wales Legislative Assembly: January Birthdays: - Hon. Carmel Tebbutt – Marrickville - Bruce Notley Smith – Coogee - Christopher Gulaptis – Terrigal - Hon. Andrew Stoner - Oxley Legislative Council: January Birthdays: - Hon. George Ajaka – Parliamentary Secretary - Charlie Lynn – Parliamentary Secretary - Hon. Gregory Pearce – Minister for Finance and Services and Minister for Illawarra South Australia Legislative Assembly January Birthdays: - Duncan McFetridge – Morphett - Hon. Mike Rann – Ramsay - Mary Thompson – Reynell - Hon. Carmel Zollo South Australian Legislative Council: No South Australian members have listed their birthdays on their website Federal January Birthdays: - Chris Bowen - McMahon, NSW - Hon. Bruce Bilson – Dunkley, VIC - Anna Burke – Chisholm, VIC - Joel Fitzgibbon – Hunter, NSW - Paul Fletcher – Bradfield , NSW - Natasha Griggs – Solomon, ACT - Graham Perrett - Moreton, QLD - Bernie Ripoll - Oxley, QLD - Daniel Tehan - Wannon, VIC - Maria Vamvakinou - Calwell, VIC - Sen. -

The 2010 Victorian State Election

Research Service, Parliamentary Library, Department of Parliamentary Services Research Paper The 2010 Victorian State Election Bella Lesman, Rachel Macreadie and Greg Gardiner No. 1, April 2011 An analysis of the Victorian state election which took place on 27 November 2010. This paper provides an overview of the election campaign, major policies, opinion polls data, the outcome of the election in both houses, and voter turnout. It also includes voting figures for each Assembly District and Council Region. This research paper is part of a series of papers produced by the Library’s Research Service. Research Papers are intended to provide in-depth coverage and detailed analysis of topics of interest to Members of Parliament. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors. P a r l i a m e n t o f V i c t o r i a ISSN 1836-7941 (Print) 1836-795X (Online) © 2011 Library, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of Parliamentary Services, other than by Members of the Victorian Parliament in the course of their official duties. Parliamentary Library Research Service Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 PART A: THE CAMPAIGN......................................................................................... 3 1. The Campaign: Key Issues, Policies and Strategies ......................................... 3 1.1 The Leaders’ Debates....................................................................................... 6 1.2 Campaign Controversies................................................................................... 7 1.3 Preference Decisions and Deals...................................................................... -

LCPC 59 01 Commencement of Sitting Day Proceedings

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Procedure Committee Commencement of sitting day proceedings Parliament of Victoria Legislative Council Procedure Committee Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER November 2019 PP No 102, Session 2018-19 ISBN 978 1 925703 92 4 (print version), 978 1 925703 93 1 (PDF version) Committee membership CHAIR DEPUTY CHAIR Hon. Shaun Leane Hon. Wendy Lovell Georgie Crozier President Deputy President Southern Metropolitan Hon. David Davis Stuart Grimley Dr Tien Kieu Southern Metropolitan Western Victoria South Eastern Metropolitan Fiona Patten Hon. Jaala Pulford Hon. Jaclyn Symes Northern Metropolitan Western Victoria Northern Victoria ii Legislative Council Procedure Committee About the Committee Functions The Procedure Committee considers any matter regarding the practices and procedure of the House and may consider any matter referred to it by the Council or the President. The following Members were appointed to the Procedure Committee on 21 March 2019: Hon. Shaun Leane, Hon. Wendy Lovell, Hon. David Davis, Ms Georgie Crozier, Mr Stuart Grimley, Dr Tien Kieu, Ms Fiona Patten, Hon. Jaala Pulford, and Hon. Jacyln Symes. The Committee held its first meeting on 1 May 2019. The President assumed the Chair and Ms Lovell was elected Deputy Chair pursuant to Standing Order 23.08(4). Staff Richard Willis, Secretary, Assistant Clerk Procedure Annemarie Burt, Research and Administration, Manager, Chamber Support Andrew Young, Advisor, Clerk Natalie Tyler, Executive Assistant to the President Contact details Address c/o Assistant Clerk Procedure, Legislative Council Parliament of Victoria Spring Street EAST MELBOURNE VIC 3002 Phone 61 3 9651 8673 Email [email protected] Web https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/procedure-committee This report is available on the Committee’s website. -

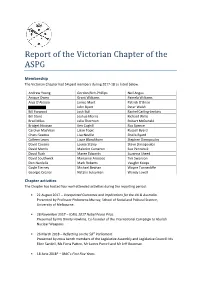

Report of the Victorian Chapter of the ASPG

Report of the Victorian Chapter of the ASPG Membership The Victorian Chapter had 54 paid members during 2017-18 as listed below. Andrew Young Gordon Rich-Phillips Neil Angus Anique Owen Grant Williams Pamela Williams Anja D’Alessio Janice Munt Patrick O’Brien John Byatt Peter Walsh Bill Forwood Josh Bull Rachel Carling-Jenkins Bill Stent Joshua Morris Richard Willis Brad Miles Julia Thornton Robert McDonald Bridget Noonan Ken Coghill Ros Spence Carolyn MacVean Lilian Topic Russell Byard Charu Saxena Lisa Neville Sheila Byard Colleen Lewis Lizzie Blandthorn Stephen Dimopoulos David Cousins Louise Staley Steve Dimopoulos David Morris Malcolm Cameron Sue Pennicuik David Rush Maree Edwards Suzanna Sheed David Southwick Marianne Aroozoo Tim Swanson Don Nardella Mark Roberts Vaughn Koops Gayle Tierney Michael Beahan Wayne Tunnecliffe Georgie Crozier Natalie Suleyman Wendy Lovell Chapter activities The Chapter has hosted four well-attended activities during the reporting period: • 22 August 2017 – Unexpected Outcomes and Implications for the UK & Australia. Presented by Professor Philomena Murray, School of Social and Political Science, University of Melbourne. • 28 November 2017 – ICAN, 2017 Nobel Peace Prize. Presented by Ms Dimity Hawkins, Co-founder of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. • 26 March 2018 – Reflecting on the 58th Parliament. Presented by cross bench members of the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council: Ms Ellen Sandell, Ms Fiona Patten, Mr James Purcell and Mr Jeff Bourman. • 18 June 2018* – IBAC’s First Five Years. Presented by Mr Alistair Maclean, Chief Executive Officer, Independent Broad-based Anti- corruption Commission. *This seminar was postponed to 23 July 2018. Corporate membership votes at AGM • ASPG Victoria Chapter is unaware of formal requests by the parent body for corporate membership, including any amounts paid. -

Investigation of Matters Referred from the Legislative Assembly on 8 August 2018

Investigation of matters referred from the Legislative Assembly on 8 August 2018 December 2019 Ordered to be published Victorian government printer Session 2018-19 P.P. No. 103 Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please call 9613 6222, using the National Relay Service on 133 677 if required, or email [email protected]. The Victorian Ombudsman pays respect to First Nations custodians of Country throughout Victoria. This respect is extended to their Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge their sovereignty was never ceded. Letter to the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly To The Honourable the President of the Legislative Council and The Honourable the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Pursuant to sections 25 and 25AA of the Ombudsman Act 1973 (Vic), I present to Parliament my: Investigation of matters referred from the Legislative Assembly on 8 August 2018. Deborah Glass OBE Ombudsman 12 December 2019 2 www.ombudsman.vic.gov.au Contents Foreword 4 Observations 79 Credit note for CML issued to Liberal Introduction 6 Party Victoria, September 2013 79 The Referral and commencement of Liberal Party Victoria’s internal controls, investigation 6 2010-2015 82 Scope and focus of the investigation 8 Structural factors 88 Evidence gathering and methodology 11 Investigation statistics 12 The Member for Lowan 90 Applicable Members’ Guide rules 90 Members’ entitlements and responsibilities 13 The email of 2 July 2018 91 The Members’ Guide 13 Discussion 98 The Electorate -

Minutes Ordinary Meeting of Council

Minutes Ordinary Meeting of Council Monday, 28th November 2016 City of Kingston Ordinary Meeting of Council Minutes 28 November 2016 Table of Contents 1. Apologies ......................................................................................................... 3 2. Confirmation of Minutes of Previous Meetings ................................................ 3 3. Foreshadowed Declaration by Councillors, Officers or Contractors of any Conflict of Interest ................................................................................. 4 [Note that any Conflicts of Interest need to be formally declared at the start of the meeting and immediately prior to the item – being considered type and nature of interest is required to be – disclosed if disclosed in writing to the CEO prior to the meeting only the type of interest needs to be disclosed prior to the item being considered.] 4. Petitions ........................................................................................................... 4 5. Presentation of Awards .................................................................................... 4 6. Reports from Delegates Appointed by Council to Various Organisations ................................................................................................... 4 7. Question Time .................................................................................................. 4 8. Planning and Development Reports ................................................................. 5 9. Community Sustainability Reports -

59Th PARLIAMENT MEMBERS of the LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL

VICTORIA - 59th PARLIAMENT MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Parliament House, Spring Street, East Melbourne Victoria 3002 (03) 9651 8678 [email protected] www.parliament.vic.gov.au As at 1 October 2021 Member (M.L.C) Region Party Address Atkinson, Mr Bruce Eastern Metropolitan LP R19B, Level 3, West 5 Car Park Entrance, Eastland Shopping Centre, 171-175 Maroondah Highway, Ringwood, VIC, 3134 (03) 9877 7188 [email protected] Bach, Dr Matthew Eastern Metropolitan LP Suite 1, 10-12 Blackburn Road, Blackburn, VIC, 3130 (03) 9878 4113 [email protected] Barton, Mr Rodney Eastern Metropolitan TM 128 Ayr Street, Doncaster, VIC, 3108 (03) 9850 8600 [email protected] https://rodbarton.com.au Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RodBartonMP/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/rodbarton4 Bath, Ms Melina Eastern Victoria NAT Shop 2, 181 Franklin Street, Traralgon, VIC, 3844 (03) 5174 7066 [email protected] Bourman, Mr Jeff Eastern Victoria SFP Unit 1, 9 Napier Street, Warragul, VIC, 3820 (03) 5623 2999 [email protected] Crozier, Ms Georgie Southern Metropolitan LP Suite 1, 780 Riversdale Road, Camberwell, VIC, 3124 (03) 7005 8699 [email protected] Cumming, Dr Catherine Western Metropolitan Ind 75 Victoria Street, Seddon, VIC, 3011 (03) 9689 6373 [email protected] Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/crcumming1/ Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/crcumming1 Davis, The Hon. David Southern Metropolitan LP 1/670 Chapel Street, South Yarra, VIC, 3141 (03) 9827 6655 [email protected] Elasmar, The Hon. -

Members of Parliament ( PDF 106.15KB)

Level of Government Name Position Address Phone / Email PO Box 102 Phone: 9808 3188 FEDERAL Gladys Liu MP Federal Member for Chisholm Burwood Vic 3125 Email: [email protected] (Level 1,140 Burwood Hwy, Burwood VIC 3125) PO Box 232 Phone: 9874 1711 The Hon Michael Sukkar MP Federal Member for Deakin Mitcham VIC 3132 Email: [email protected] (Unit 5/602 Whitehorse Road, Mitcham VIC 3132) PO Box 1253 Phone: 9882 3677 The Hon Josh Frydenberg MP Federal Member for Kooyong Camberwell Vic 3124 Email: [email protected] (145 Camberwell Road, Hawthorn East Vic 3123) PO Box 4307 Phone: 9887 0255 STATE The Hon Shaun Leane MLC Member for Eastern Metropolitan Knox City Centre VIC 3152 Email: [email protected] Region (Suite 3, Level 2, 420 Burwood Highway Wantirna VIC 3152) PO Box 508 Phone: 9877 7188 The Hon Bruce Atkinson MLC Member for Eastern Metropolitan Ringwood, 3134 Email: [email protected] Region (R19B, Level 3 West 5 Car Park Entrance, Eastland Shopping Centre, 171-175 Maroondah Highway, Ringwood VIC 3134) Suite 1, 10-12 Blackburn Road Phone: 9878 4113 Member for Eastern Metropolitan Dr Matthew Bach MLC Blackburn VIC 3130 Email: [email protected] Region 56 Beetham Parade Phone: 9803 0592 Member for Eastern Metropolitan Sonja Terpstra MLC Rosanna Vic 3084 Email: [email protected] Region 128 Ayr Street Phone: 9850 8600 Member for Eastern Metropolitan Rodney Barton MLC Doncaster VIC 3108 Email: [email protected] Region Vogue -

ABALINX ENEWS LETTER 12 Liberal Party of Australia (Victorian Division)

ABALINX NEWSLETTER 1. This is the first of many newsletters yet to come. The information provided is only as good as the sources who provide it and even then one must be cautious when taking such news on board. Today in the world of technology where Artificial Intelligence reigns supreme it is difficult to separate the truth from fiction and vice versa. Yet we shall try to remain as factual as much as possible. WHAT HAPPENED TO KARINA OKOTEL? While I have always found her charming, invigorating, informative and very engaging; the once rising star Karina Okotel has disappeared from political view. Members are asking questions why is she is absent. Has her political that her star has dimmed, fallen or extinguished? I am told by senior Conservatives that nationally Karina had lost their support. In fact it is alleged that she had run around visiting the offices of Senators attempting to gain their support. What in fact happened was that all of the Senators being pursued abandoned her before the Federal ballot and carried only support from twenty dissident members. Some are even saying that Karina has been dealt a political snub and has been ostracised from the Liberal Party for her disloyal political behaviour. Now others in the so called know are using innuendoes, gossip, whispers to accuse her of alleged disloyalty after all her good work. It has been alleged that Karina actively worked against the past President Michael Kroger and undermined him rather than working with him. But I ask myself whether this is mere scuttlebutt and misinformation or is there more to her disappearing from the political scene.