NAG FS006 97 Hay&Pellets-JONI FEB 24

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda - Mammals and Mountains

Uganda - Mammals and Mountains Naturetrek Tour Report 9th - 21st January 2005 Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk All photos by Peter Price Front page (clockwise from top): African Finfoot, Mountain Gorilla, African Fish Eagle, Mountain Gorilla Above (clockwise from top): Pied Kingfisher, Malachite Kingfisher Citrus Swallowtail, Mountain Gorilla Uganda - Mammals and Mountains Tour Report Day 1 Sunday 9th January The group departed London Heathrow on a scheduled British Airways flight that departed at 2125 hours. Day 2 Monday 10th January We arrived at Entebbe International airport early this morning and having completed the usual airport formalities without any problems we met our Churchill Safaris guides, Alfred and Suza, waiting for us. We were soon on the road and drove from Entebbe into the bustling Kampala for a brief stop before driving south-westwards towards Lake Mburo National Park. We stopped for a late light lunch on the side of the road at a small, very clean restaurant only a few yards from the equator. A nearby tree was full of active Black-headed Weaver nests, a swallow perched on a roadside wire was eventually identified as Angola Swallow (very similar to our own Barn Swallow), a Black- shouldered Kite was hunting nearby – interesting species of bird weren’t in short supply. After lunch we continued our drive to our destination for that evening, Mantana Luxury Tented Camp. We arrived at the park with time to look at our first African mammals of the trip. -

A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates

veterinary sciences Review A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates Hendrik Swanepoel 1,2, Jan Crafford 1 and Melvyn Quan 1,* 1 Vectors and Vector-Borne Diseases Research Programme, Department of Veterinary Tropical Disease, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0110, South Africa; [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (J.C.) 2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Institute of Tropical Medicine, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-12-529-8142 Abstract: (1) Background: Viral diseases are important as they can cause significant clinical disease in both wild and domestic animals, as well as in humans. They also make up a large proportion of emerging infectious diseases. (2) Methods: A scoping review of peer-reviewed publications was performed and based on the guidelines set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews. (3) Results: The final set of publications consisted of 145 publications. Thirty-two viruses were identified in the publications and 50 African ungulates were reported/diagnosed with viral infections. Eighteen countries had viruses diagnosed in wild ungulates reported in the literature. (4) Conclusions: A comprehensive review identified several areas where little information was available and recommendations were made. It is recommended that governments and research institutions offer more funding to investigate and report viral diseases of greater clinical and zoonotic significance. A further recommendation is for appropriate One Health approaches to be adopted for investigating, controlling, managing and preventing diseases. Diseases which may threaten the conservation of certain wildlife species also require focused attention. -

Transboundary Species Project

TRANSBOUNDARY SPECIES PROJECT ROAN, SABLE AND TSESSEBE Rowan B. Martin Species Report for Roan, Sable and Tsessebe in support of The Transboundary Mammal Project of the Ministry of Environment and Tourism, Namibia facilitated by The Namibia Nature Foundation and World Wildlife Fund Living in a Finite Environment (LIFE) Programme Cover picture adapted from the illustrations by Clare Abbott in The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion by Reay H.N. Smithers Published by the University of Pretoria Republic of South Africa 1983 Transboundary Species Project – Background Study Roan, Sable and Tsessebe CONTENTS 1. BIOLOGICAL INFORMATION ...................................... 1 a. Taxonomy ..................................................... 1 b. Physical description .............................................. 3 c. Habitat ....................................................... 6 d. Reproduction and Population Dynamics ............................. 12 e. Distribution ................................................... 14 f. Numbers ..................................................... 24 g. Behaviour .................................................... 38 h. Limiting Factors ............................................... 40 2. SIGNIFICANCE OF THE THREE SPECIES ........................... 43 a. Conservation Significance ........................................ 43 b. Economic Significance ........................................... 44 3. STAKEHOLDING ................................................. 48 a. Stakeholders ................................................. -

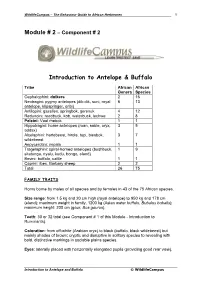

Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo

WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 1 Module # 2 – Component # 2 Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo Tribe African African Genera Species Cephalophini: duikers 2 16 Neotragini: pygmy antelopes (dik-dik, suni, royal 6 13 antelope, klipspringer, oribi) Antilopini: gazelles, springbok, gerenuk 4 12 Reduncini: reedbuck, kob, waterbuck, lechwe 2 8 Peleini: Vaal rhebok 1 1 Hippotragini: horse antelopes (roan, sable, oryx, 3 5 addax) Alcelaphini: hartebeest, hirola, topi, biesbok, 3 7 wildebeest Aepycerotini: impala 1 1 Tragelaphini: spiral-horned antelopes (bushbuck, 1 9 sitatunga, nyalu, kudu, bongo, eland) Bovini: buffalo, cattle 1 1 Caprini: ibex, Barbary sheep 2 2 Total 26 75 FAMILY TRAITS Horns borne by males of all species and by females in 43 of the 75 African species. Size range: from 1.5 kg and 20 cm high (royal antelope) to 950 kg and 178 cm (eland); maximum weight in family, 1200 kg (Asian water buffalo, Bubalus bubalis); maximum height: 200 cm (gaur, Bos gaurus). Teeth: 30 or 32 total (see Component # 1 of this Module - Introduction to Ruminants). Coloration: from off-white (Arabian oryx) to black (buffalo, black wildebeest) but mainly shades of brown; cryptic and disruptive in solitary species to revealing with bold, distinctive markings in sociable plains species. Eyes: laterally placed with horizontally elongated pupils (providing good rear view). Introduction to Antelope and Buffalo © WildlifeCampus WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 2 Scent glands: developed (at least in males) in most species, diffuse or absent in a few (kob, waterbuck, bovines). Mammae: 1 or 2 pairs. Horns. True horns consist of an outer sheath composed mainly of keratin over a bony core of the same shape which grows from the frontal bones. -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Pigs (Suidae)

Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Team Leader, Toni’s Zoo, Rothenburg, Luzern, Switzerland Email: [email protected] 9th May 2021 Cover photo © Krisztián Svábik Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Use of space and enclosure furnishings ................................................................... 3 Feeding ..................................................................................................................... 3 Breeding ................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of species and individuals ............................................................................ 4 List of mixed-species exhibits involving Suids ........................................................ 5 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – SUIDAE .......................................................... 6 Sulawesi Babirusa, Babyrousa celebensis ...............................................................7 Common Warthog, Phacochoerus africanus ......................................................... 8 Giant Forest Hog, Hylochoerus meinertzhageni ..................................................10 Bushpig, Potamochoerus larvatus ........................................................................ 11 Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus ............................................................... -

Speaker Notes

Malignant Catarrhal Fever S Malignant catarrhal fever is an infectious disease of ruminants. It is also l referred to as malignant catarrh, malignant head catarrh, gangrenous i coryza, catarrhal fever, and snotsiekte, which is a South African word meaning "snotting sickness“. d Malignant Catarrhal Fever e Malignant Catarrh, Malignant Head Catarrh, Gangrenous Coryza, Catarrhal Fever, 1 Snotsiekte S In today’s presentation we will cover information regarding the organism l Overview that causes Malignant Catarrhal Fever and its epidemiology. We will also i • Organism talk about the economic impact the disease has had in the past and could • Economic Impact have in the future. Additionally, we will talk about how it is transmitted, d • Epidemiology the species it affects, clinical and necropsy signs seen, and diagnosis and e • Transmission treatment of the disease. Finally, we will address prevention and control • Clinical Signs • Diagnosis and Treatment measures for the disease as well as actions to take if Malignant Catarrhal 2 • Prevention and Control Fever is suspected. • Actions to Take Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011 (Photo: Hartebeest) S l i d The Organism e 3 S Malignant catarrhal fever (MCF) is caused by several viruses in the genus l The Organism Rhadinovirus of the family Herpesviridae (subfamily i • Herpesviridae Gammaherpesvirinae). The specific serotype varies depending on species – Genus Rhadinovirus and geographic distribution. Wildebeest in Africa are the natural host d • Multiple serotypes species that carry the alcelaphine herpesvirus-1 (AHV-1). All varieties of e – Species and geographically dependent • AHV-1 natural host: wildebeest in Africa domestic sheep, as well as goats, in North America and throughout the • OHV-2 natural host: domestic sheep and goats worldwide world are carriers of ovine herpesvirus-2 (OHV-2); this serotype is the 4 • AHV-2 nonpathogenic major cause of MCF worldwide. -

Malignant Catarrhal Fever

Amb~vomma are present in the USA. Are they potential Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. Trop Anim Hlth Prod. I. ( 1969): 119-130. - vectors of pathogenic T. mutans? Amb~vomma variegatum 4. Brocklesby, D. W .• and Bailey. K. P.: Oxytetracycline Hydrochloride is now present in Puerto Rico and is a proven vector of in East Coast Fever (Thl!ileria pan1a Infection). Brit Yet J. I 18. ( 1962): 81- 85 . - 5. Brocklesby. D. W .. and Bailey. K. P.: The Immunization of Cattle pathogenic theilerias. Numerous wild African ungulates are against East Coast Fever (Theileria parva Infection) Using Tetracyclines: A introduced into the USA each year. They could carry in review of the Literature and a Reappraisal of the Method. Bull Epiz Dis theilerias since 24 species have been shown to be carriers of Afr. 13, (1965): 161-168. - 6. Burridge. M. J.: Application ofthe Indirect theilerias-like organisms. Fluorescent Antibody Test in Experimental East Coast Fever (Theileria parva Infection of Cattle). Res Vet Sci, 12. (1971): 338-341. - 7. All of these facts make it obvious that the possibility exists Cunningham, M. P .• and others: Immunization Against East Coast Fever, that T. parva could become established in the United States the Relationship between Infective Dose and the Severity of the Disease in of America if it were introduced. Cattle. J Parasitol, 58. (1970): 61 (966). - 8. Hulliger. L. : Cultivation of Three Species of Theileria in Lymphoid Cells in 1•itro. J Protozool, 12, ( 1965): 649-655. - 9. Malmquist, W. A .. and Brown, C. G. D.: Cell Culture of Theileria parva. J Parasitol. 56, ( 1970): 66-67 (975). -

GNUSLETTER Vol 37#2.Pdf

GNUSLETTER Volume 37 / Number 2 December 2020 ANTELOPE SPECIALIST GROUP IUCN Species Survival Commission Antelope Specialist Group GNUSLETTER is the biannual newsletter of the IUCN Species Survival Commission Antelope Specialist Group (ASG). First published in 1982 by first ASG Chair Richard D. Estes, the intent of GNUSLETTER, then and today, is the dissemination of reports and information regarding antelopes and their conservation. ASG Members are an important network of individuals and experts working across disciplines throughout Africa, Asia and America. Contributions (original articles, field notes, other material relevant to antelope biology, ecology, and conservation) are welcomed and should be sent to the editor. Today GNUSLETTER is published in English in electronic form and distributed widely to members and non-members, and to the IUCN SSC global conservation network. To be added to the distribution list please contact [email protected]. GNUSLETTER Editorial Board - David Mallon, ASG Co-Chair - Philippe Chardonnet, ASG Co-Chair ASG Program Office - Tania Gilbert, Marwell Wildife The Antelope Specialist Group Program Office is hosted and supported by Marwell Wildlife https://www.marwell.org.uk The designation of geographical entities in this report does not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of IUCN, the Species Survival Commission, or the Antelope Specialist Group concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or concerning the delimitation of any frontiers or boundaries. Views expressed in GNUSLETTER are those of the individual authors, Cover photo: Young female bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus), W National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Niger (© Daniel Cornélis) 2 GNUSLETTER Volume 37 Number 2 December 2020 FROM IUCN AND ASG………………………………………………………. -

Ground Counts for Medium to Large Mammals in Pian Upe Wildlife Reserve Karamoja, Uganda

GROUND COUNTS FOR MEDIUM TO LARGE MAMMALS PIAN-UPE WILDLIFE - 2018 GROUND COUNTS FOR MEDIUM TO LARGE MAMMALS IN PIAN UPE WILDLIFE RESERVE KARAMOJA, UGANDA Report by F. E. Kisame, F. Wanyama, E. Buhanga and A. Rwetsiba Uganda Wildlife Authority 2018 I UGANDA WILDLIFE AUTHORITY TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS IV ABSTRACT V 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1. POPULATION ESTIMATES AND SURVEYS 1 1.2. THE OBJECTIVES FOR THE SURVEY WERE: 1 2.0 SURVEY AREA AND METHODS 2.1. LOCATION OF THE SURVEY AREA: 2 2.2. DESCRIPTION OF THE SURVEY AREA 2 2.3. METHOD (FOOT - TRANSECT SURVEY) 3 2.3.1. Survey design 3 2.3.2. Data collection 3 3.0 RESULTS 5 3.1. DISTRIBUTION 6 3.1.1. Direct observations 6 3.1.2. Distribution of carnivore species by spoors in Pian Upe Wildlife Reserve 11 3.1.3. Distribution of buffalo and topi by spoors in Pian Upe Wildlife Reserve 12 3.2. HUMAN ACTIVITIES 12 3.2.1. Distribution of settlements and cultivation activities in PUWR 14 4.0 DISCUSSION Roan antelope Hippotragus equinus 16 Mountain reedbuck Redunca fulvorufula 16 Gazelle 16 Bushbucks Tragelaphus scriptus 16 Bohor’s Reedbuck Redunca redunca 16 Waterbuck Kobus ellipsiprymnus ssp. defassa 16 Zebra 17 Klipspringer Oreotragus oreotragus 17 Eland Tragelaphus oryx 17 Hartebeest Alcelaphus buselaphus 17 5.0 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 6.0 REFERENCES 20 7.0 APPENDICES 21 Appendix I. Teams preparing to start the survey 21 II GROUND COUNTS FOR MEDIUM TO LARGE MAMMALS PIAN-UPE WILDLIFE - 2018 FIGURES Figure 1. Map of Uganda showing the location of Pian Upe Wildlife Reserve (2018). -

Hadrosaurs As Ungulate Parallels: Lost Lifestyles and Deficient Data

Hadrosaurs as ungulate parallels: Lost lifestyles and deficient data MATTHEW T. CARRANO, CHRISTINE M. JANIS, and J. JOHN SEPKOSKI,JR.? Carrano, M.T, Janis, C.M., & Sepkoski, J.J., Jr. 1999. Hadrosaurs as ungulate parallels: Lost Lifestyles and deficient data. -Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 44,3,237-261. Hadrosaur dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Hadrosauridae) were abundant in Late Cretaceous terrestrial environments of North America and Asia. Their derived dental and postcranial specializations for herbivory have led to the suggestion that these dinosaurs were analo- gous to modem ungulates in lifestyle. Ungulates display a suite of morphological fea- tures that are correlated with diet, habitat preference, and sexual dimorphism. In this pa- per we examine several of these same features in hadrosaurs in order to determine whether they display similar patterns under multivariate analysis. Initial results confirm the resemblances between hadrosaurs and ungulates but suggest that missing data may considerably affect the outcomes of statistical analyses. Using the hadrosaur dataset as a template, we artificially degrade the (previously complete) ungulate datasets and per- form the same analyses. Results are consistent with earlier results and provide an oppor- tunity to assess the impact of missing data on the original multivariate structure. Our re- sults support the hypothesis that hadrosaurs were similar to ungulates in patterns of ecomorphology. Key words : Dinosauria, Ornithischia, Ornithopoda, multivariate statistics, paleoeco- logy, Marnmalia, NMDS. Matthew T. Carrano [[email protected]],Department of Anatomical Sci- ences, Health Sciences Center T-8, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, New York, 11 794 USA. Christine M. Janis [[email protected]], Department of Ecology and Evolution- ary Biology, Division of Biology and Medicine, Box G-B209, Brown University, Provi- dence, Rhode Island, 02912 USA. -

Diapositive 1

Niche overlap and resource partitioning between rare topi antelope (Damaliscus korrigum) and other sympatric bulk grazers in Pendjari Biosphere Reserve (Northern Benin): Implication for topi conservation Chabi A.M.S. Djagoun1, Brice Sinsin, Nicole Wrage-Mönnig 1 Contact Email:[email protected] Mammalian herbivores – Diversity and global distribution Orders Families Genera Species Africa 4 9 45 107 Eurasia 3 10 38 84 Americas 2 6 20 35 African refuge? African Codron D (2013) In: Grzimek B, MacLeod N, Archibald JD, Levin PS, Blanchfield DS (eds) Grzimek's animal life encyclopedia: Extinction. Gale/Cengage Learning, Detroit, pp 385-395 To prevent from biodiversity extinction PA have been created worldwide including Africa Worldwide: large mammal populations are restricted to protected areas of Low - minimal human disturbance High - density density opulation p Cause: Human population growth and mammal land transformations also negatively influence ungulate population dynamics large large Human - - through the degradation and destruction of animal natural habitats Low High with high exploitation (Ogutu et al., 2009) NETWORK OF BENIN PROTECTED AREA Reduncinae •Redunca redunca Population: 957 Diet: Gr •Kobus defassa GRAZER Population: 1235 ind Diet: MF herbivores •Kobus kob Population: 12513 ind Diet: Gr diversity – Population Alcelaphinae Density in Pendjari •Damaliscus lunatus Population: 209 ind Diet: Gr Biosphere •Alcelaphus buselaphus Reserve Population: 1117 ind Diet: Gr Hippotraginae •Hippotragus equinus Bovinae Population: 2975 ind Diet: Gr •Syncerus cafer Population: 14450 ind Diet: Gr •Tragelaphus scriptus Population: 42Kg Diet: Br One of the major problems associated with management of animal community confined in protected area is the accommodation of the number of different species in equilibrium with one another and their natural environment. -

Lake Mburo—A New National Park in Africa Jonathan Kingdon

Lake Mburo—a new national park in Africa Jonathan Kingdon The opening of a new national park in Uganda On the morning of Saturday 14 July 1984 a cloud is significant and welcome evidence of the of dust rose into the sky as lorries, landrovers and resuscitation of the country's commitment to cars made their way over a hastily laid track that conservation. The author, an FFPS Council led to a low hill overlooking Lake Mburo. School member, who has a long and active assoc- children and students, workers and businessmen, iation with Uganda, attended the ceremonial dancers, bands, politicians and scientists con- opening of Lake Mburo National Park last July. verged in a noisy cheerful crowd on this spot in He tells the story behind the achievement and south-western Uganda to celebrate a very makes a plea for international support to remarkable event— the birth of a new national enable Uganda to sustain its efforts to reverse park in one of the loveliest areas of Uganda. Few the trend towards environmental degradation. people at the ceremony and practically no one Klipspringer in Lake Mburo National Park (J.B. White). A new national park in Africa Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.203.74, on 07 Oct 2021 at 15:14:37, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605300019475 outside Uganda was likely to appreciate the scale in the late 1950s and 1960s was made possible by of this achievement.