The Development of Dogma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating the Sociology of First Amendment Silence Mae Kuykendall

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 42 Article 3 Number 4 Summer 2015 1-1-2015 Evaluating the Sociology of First Amendment Silence Mae Kuykendall Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Mae Kuykendall, Evaluating the Sociology of First Amendment Silence, 42 Hastings Const. L.Q. 695 (2015). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol42/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evaluating the Sociology of First Amendment Silence by MAE KUYKENDALL* Introduction Silence is that curious answer to the riddle, "What is golden and disappears when you speak its name?" In the context of First Amendment jurisprudence, Silence is just as puzzling as a riddle. Silence may be used as a verb, as in, to cause a speaker to cease speaking or as a noun, as in, the absence of speaking or sound. In either form, Silence has long been recognized as a rhetorical vehicle for expression. As it is wont to do, Silence often sits quietly in the interstices of First Amendment doctrine. But when she speaks, she roars. When Silence becomes speech, and that speech becomes law, Silence can get a thumping for its unseemly intrusion. The thumping of silence as legal doctrine, such as it has been, was a product of the Court's rescue of the Boy Scouts in Boy Scouts of America v. -

People's Power

#2 May 2011 Special Issue PersPectives Political analysis and commentary from the Middle East PeoPle’s Power the arab world in revolt Published by the Heinrich Böll stiftung 2011 This work is licensed under the conditions of a Creative Commons license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. You can download an electronic version online. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: Attribution - you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work); Noncommercial - you may not use this work for commercial purposes; No Derivative Works - you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. editor-in-chief: Layla Al-Zubaidi editors: Doreen Khoury, Anbara Abu-Ayyash, Joachim Paul Layout: Catherine Coetzer, c2designs, Cédric Hofstetter translators: Mona Abu-Rayyan, Joumana Seikaly, Word Gym Ltd. cover photograph: Gwenael Piaser Printed by: www.coloursps.com Additional editing, print edition: Sonya Knox Opinions expressed in articles are those of their authors, and not HBS. heinrich böll Foundation – Middle east The Heinrich Böll Foundation, associated with the German Green Party, is a legally autonomous and intellectually open political foundation. Our foremost task is civic education in Germany and abroad with the aim of promoting informed democratic opinion, socio-political commitment and mutual understanding. In addition, the Heinrich Böll Foundation supports artistic, cultural and scholarly projects, as well as cooperation in the development field. The political values of ecology, democracy, gender democracy, solidarity and non-violence are our chief points of reference. -

Conservation and the Myth of Consensus

Essays Conservation and the Myth of Consensus M. NILS PETERSON,∗ MARKUS J. PETERSON,† AND TARLA RAI PETERSON‡ ∗Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Michigan State University, 13 Natural Resources Building, East Lansing, MI 48824-1222, U.S.A., email [email protected] †Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-2258, U.S.A. ‡Department of Communication, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0491, U.S.A. Abstract: Environmental policy makers are embracing consensus-based approaches to environmental de- cision making in an attempt to enhance public participation in conservation and facilitate the potentially incompatible goals of environmental protection and economic growth. Although such approaches may pro- duce positive results in immediate spatial and temporal contexts and under some forms of governance, their overuse has potentially dangerous implications for conservation within many democratic societies. We suggest that environmental decision making rooted in consensus theory leads to the dilution of socially powerful con- servation metaphors and legitimizes current power relationships rooted in unsustainable social constructions of reality. We also suggest an argumentative model of environmental decision making rooted in ecology will facilitate progressive environmental policy by placing the environmental agenda on firmer epistemological ground and legitimizing challenges to current power hegemonies that dictate unsustainable practices. Key Words: democracy, environmental conflict, -

The Opposition to Israel's Withdrawal from the Gaza Strip: Legi

1 ENGL 114 Professor Andrew Ehrgood The Opposition to Israel's Withdrawal from the Gaza Strip: Legitimizing Civil Disobedience from Both Sides of the Political Map by Aya Shoshan The Left Faces an Unexpected Dilemma As an Israeli leftist, I shared the left’s excitement when, in February 2004, Prime Minister Sharon announced his plan to withdraw from the Gaza strip. Even though this wasn't the peace agreement that the left craved for, no one could ignore the historical importance of this decision. The dominant view among the left was that after 38 years of occupation of Palestinian territories, Israel was finally acknowledging that the occupation was destructive. The withdrawal was also a precedent for evacuating other Israeli settlements. If the plan proved feasible, it would make way for other evacuations in the future. Finally, that the decision to withdraw had been made by a right-wing government meant that the understanding of the need to withdraw had crossed political boundaries and become a consensus. In the midst of this enthusiasm, disturbing voices of resistance appeared from the far right. Aside from expected protests against the withdrawal, some right-wing leaders and activists called for more severe steps, such as refusing to serve in the military and physically resisting the evacuation of settlements. These statements outraged the left. How dare the settlers, who have been nurtured by the state for years, who have taken pride in being patriotic and loyal to the state, who have dragged Israel into countless unnecessary confrontations with the Palestinians, how dare they turn their back on the law and the government now? There was an immense urge among the left to denounce the right resistance, and many left-wing activists and thinkers joined forces to do so. -

Virality : Contagion Theory in the Age of Networks / Tony D

VIRALITY This page intentionally left blank VIRALITY TONY D. SAMPSON UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA PRESS Minneapolis London Portions of chapters 1 and 3 were previously published as “Error-Contagion: Network Hypnosis and Collective Culpability,” in Error: Glitch, Noise, and Jam in New Media Cultures, ed. Mark Nunes (New York: Continuum, 2011). Portions of chapters 4 and 5 were previously published as “Contagion Theory beyond the Microbe,” in C Theory: Journal of Theory, Technology, and Culture (January 2011), http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=675. Copyright 2012 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sampson, Tony D. Virality : contagion theory in the age of networks / Tony D. Sampson. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8166-7004-8 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8166-7005-5 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Imitation. 2. Social interaction. 3. Crowds. 4. Tarde, Gabriel, 1843–1904. I. Title. BF357.S26 2012 302'.41—dc23 2012008201 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Dedicated to John Stanley Sampson (1960–1984) This page intentionally left blank Contents Introduction 1 1. -

Clarifying the Structure and Nature of Left-Wing Authoritarianism

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology PREPRINT © 2021 American Psychological Association In press. Not the version of record. Final version DOI: 10.1037/pspp0000341 Clarifying the Structure and Nature of Left-wing Authoritarianism Thomas H. Costello, Shauna M. Bowes Sean T. Stevens Emory University New York University Foundation for Individual Rights in Education Irwin D. Waldman, Arber Tasimi Scott O. Lilienfeld Emory University Emory University University of Melbourne Authoritarianism has been the subject of scientific inquiry for nearly a century, yet the vast majority of authoritarianism research has focused on right-wing authoritarianism. In the present studies, we inves- tigate the nature, structure, and nomological network of left-wing authoritarianism (LWA), a construct famously known as “the Loch Ness Monster” of political psychology. We iteratively construct a meas- ure and data-driven conceptualization of LWA across six samples (N = 7,258) and conduct quantitative tests of LWA’s relations with over 60 authoritarianism-related variables. We find that LWA, right- wing authoritarianism, and social dominance orientation reflect a shared constellation of personality traits, cognitive features, beliefs, and motivational values that might be considered the “heart” of au- thoritarianism. Still, relative to right-wing authoritarians, left-wing authoritarians were lower in dog- matism and cognitive rigidity, higher in negative emotionality, and expressed stronger support for a political system with substantial centralized state control. Our results also indicate that LWA power- fully predicts behavioral aggression and is strongly correlated with participation in political violence. We conclude that a movement away from exclusively right-wing conceptualizations of authoritarian- ism may be required to illuminate authoritarianism’s central features, conceptual breadth, and psycho- logical appeal. -

Popular Uprisings and Philippine Democracy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UW Law Digital Commons (University of Washington) Washington International Law Journal Volume 15 Number 1 2-1-2006 It's All the Rage: Popular Uprisings and Philippine Democracy Dante B. Gatmaytan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Dante B. Gatmaytan, It's All the Rage: Popular Uprisings and Philippine Democracy, 15 Pac. Rim L & Pol'y J. 1 (2006). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol15/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington International Law Journal by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2006 Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal Association IT’S ALL THE RAGE: POPULAR UPRISINGS AND PHILIPPINE DEMOCRACY † Dante B. Gatmaytan Abstract: Massive peaceful demonstrations ended the authoritarian regime of Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines twenty years ago. The “people power” uprising was called a democratic revolution and inspired hopes that it would lead to the consolidation of democracy in the Philippines. When popular uprisings were later used to remove or threaten other leaders, people power was criticized as an assault on democratic institutions and was interpreted as a sign of the political immaturity of Filipinos. The literature on people power is presently marked by disagreement as to whether all popular uprisings should be considered part of the people power tradition. -

WPA/ISSPD Educational Program on Personality Disorders

WPA/ISSPD Educational Program on Personality Disorders Editors Erik Simonsen, M.D., chair Elsa Ronningstam, Ph.D. Theodore Millon, Ph.D., D.Sc. December 2006 International Advisory panel John Gunderson, USA Roger Montenegro, Argentina Charles Pull, Luxembourg Norman Sartorius, Switzerland Allan Tasman, USA Peter Tyrer, UK 2 Authors Module I Authors Module II Renato D. Alarcon, USA Anthony W. Bateman, UK Judith Beck, USA Robert F. Bornstein, USA G.E. Berrios, UK Vicente Caballo, Spain Vicente Caballo, Spain David J. Cooke, UK Allen Frances, USA Peter Fonagy, UK Glen O. Gabbard, USA Stephen D. Hart, Canada Seth Grossmann, USA Elisabeth Iskander, USA W. John Livesley, Canada Yutaka Ono, Japan Juan J. Lopez-Ibor, Spain J. Christopher Perry, Canada Theodore Millon, USA Bruce Pfohl, USA Joel Paris, Canada Elsa Ronningstam, USA Robert Reugg, USA Henning Sass, Germany Michael Rutter, UK Reinhild Schwarte, Germany Erik Simonsen, Denmark Larry J. Siever, USA Peter Tyrer, UK Michael H. Stone, USA Irving Weiner, USA Svenn Torgersen, Norway Drew Westen, USA Reviewer Module I Reviewers Module II Melvin Sabshin, USA/UK David Bernstein, USA Sigmund Karterud, Norway Cesare Maffei, Italy John Oldham, USA James Reich, USA 3 Authors Module III Reviewers Module III R.E. Abraham, The Netherlands Anthony Bateman, UK Claudia Astorga, Argentina Robert Bornstein, USA Marco Aurélio Baggio, Brazil Vicente Caballo, Spain Yvonne Bergmans, Canada Glen O. Gabbard, USA Mirrat Gul Butt, Pakistan Yutaka Ono, Japan H.R. Chaudhry, Pakistan Elsa Ronningstam, USA Dirk Corstens, The Netherlands Henning Sass, Germany Kate Davidson, UK Erik Simonsen, Denmark Mircea Dehelean, Romania Allan Tasman, USA Andrea Fossati, Italy E. -

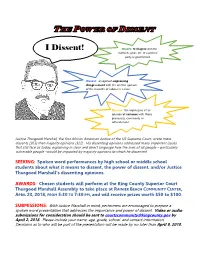

I Dissent! Dissent: to Disagree with the Methods, Goals, Etc

I Dissent! Dissent: to disagree with the methods, goals, etc. of a political party or government. Dissent: an opinion expressing disagreement with the written opinion of the majority of judges in a case. Dissent: to disagree with the methods, goals, etc. of a politicalDissent: the expression of an opinion at variance with those party or governmentpreviously, commonly or officially held. Justice Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Justice of the US Supreme Court, wrote more dissents (363) than majority opinions (322). His dissenting opinions addressed many important issues that still face us today, explaining in clear and direct language how the lives of all people – particularly vulnerable people –would be impacted by majority opinions to which he dissented. SEEKING: Spoken word performances by high school or middle school students about what it means to dissent, the power of dissent, and/or Justice Thurgood Marshall’s dissenting opinions. AWARDS: Chosen students will perform at the King County Superior Court Thurgood Marshall Assembly to take place at RAINIER BEACH COMMUNITY CENTER, APRIL 23, 2018, FROM 5:30 TO 7:30 PM, and will receive prizes worth $50 to $100. SUBMISSIONS: With Justice Marshall in mind, performers are encouraged to prepare a spoken word presentation that addresses the importance and power of dissent. Video or audio submissions for consideration should be sent to [email protected] by April 2, 2018. Please include your name, age, grade, school, and contact information. Decisions as to who will be part of the presentation will be made by no later than April 9, 2018. Submission Information: This information is provided to assist with submissions for participation in the King County Superior Court’s Justice Thurgood Marshall Assembly on April 23, 2018 at the Rainier Beach Community Center from 5:30 to 7:30 PM. -

Nussbaum's Concept of Cosmopolitanism

Paideusis, Volume 15 (2006), No. 2, pp. 51-60 Nussbaum’s Concept of Cosmopolitanism: Practical Possibility or Academic Delusion? M. AYAZ NASEEM and EMERY J. HYSLOP-MARGISON Concordia University, Canada In this paper, we explore Martha Nussbaum’s version of cosmopolitanism and evaluate its potential to reduce the growing global discord we currently confront. We begin the paper by elucidating the concept of cosmopolitanism in historical and contemporary terms, and then review some of the major criticisms of Nussbaum’s position. Finally, we suggest that Nussbaum’s vision of cosmopolitanism, in spite of its morally noble intentions, faces overwhelming philosophical and practical difficulties that undermine its ultimate tenability as an approach to resolving international conflict. Introduction During the present period of rapid economic globalization and widespread international conflict there are obvious and compelling reasons to enhance understanding and cooperation among individuals from different cultures and regions of the world. The promise of creating a cosmopolitan, or global, citizen, then, in an effort to reduce or eliminate conflict between cultures and nations understandably appeals to many individuals. In this paper, we explore Martha Nussbaum’s version of cosmopolitanism and evaluate its potential to reduce the growing global discord we currently confront. We begin the paper by elucidating the concept of cosmopolitanism in historical and contemporary terms, and then review some of the major criticisms of Nussbaum’s position. Finally, we suggest that Nussbaum’s vision of cosmopolitanism, in spite of its morally noble intentions, faces overwhelming philosophical and practical difficulties that undermine its ultimate tenability as an approach to resolving international conflict. -

Informal Types of Eclecticism in Psychotherapy

Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome © 2012 Italian Area Group of the Society for Psychotherapy Research 2012, Vol. 15, No. 1, 10-21 ISSN 2239-8031 DOI: 10.7411/RP.2012.002 When Therapists Do Not Know What to Do: Informal Types of Eclecticism in Psychotherapy Diego Romaioli1 and Elena Faccio2 Abstract. Eclecticism usually arises from the perception of one’s own theoretical model as being inadequate, which may be the case in situations of therapeutic stalemate. In need of new strategies, therapists criticize their own approach and take eclectic knowledge onboard. The goal of this qualitative study is to explore basic elements of this informal knowledge, with reference to the theory of social representations and points of view. Episodic interviews were conducted with 40 therapists. Results confirmed that clinical knowledge often turns eclectic, showing different styles of reorganization; a so- cial co-evolution model will be pointed out to explain this personalization of one’s own approach. The results achieved might contribute to the amelioration of the therapeutic awareness of one’s own knowledge structure and the use of eclecticism in carrying out therapies, leading to significant benefit in treatment effectiveness. Keywords: psychotherapy, eclecticism, social representations, points of view, quali- tative methodology Clinical intervention is increasingly structured lecticism is called technical eclecticism (Lazarus & according to an eclectically oriented style of psy- Beutler, 1993; Lazarus, Beutler, & Norcross, 1992; chotherapy; such eclecticism is encouraged as a way Norcross, 1986) and prescribes the use of the most that allows the therapist—through the use of a dif- promising techniques after having proven their ef- ferent theoretical frame—to expand the possibility ficacy through scientific research studies (Beutler & of understanding the client’s issues better (Slife, Clarkin, 1990). -

Chinese Cosmopolitanism in Two Senses and Postcolonial National Memory

UC Berkeley New Faculty Lecture Series (formerly Morrison Library Inaugural Address) Title Chinese Cosmopolitanism in Two Senses and Postcolonial National Memory Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8qv9f5tv Author Cheah, Pheng Publication Date 2000 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California *r. r i -s. n :L i b- r a r- y . n a.u g. u r a I' .. .. A d d r e s. s S e r iae s : Chin'e.s'e Co$m0polhanism -ih Two,Sens6s an&Postcolo'nial Ndtio'n"al Meinory I ., : University of Calif6rnia, Berkeley 2000 Morrison Library Inaugural Address Series No. 19 Editorial Board Jan Carter, issue editor Carlos R. Delgado, series editor Morrison Library:-Alex Warren Text format and design.y-Mary-ScottScott Forthcopning in Cosmopolitan,Geographics: New Locations of Literature and Culture. N.Y.: Routledge, 2000. Reprinted with permission. ISSN: 1079-2732 Publisbed by: The' Doe Library University of California Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 We wish to thank the Rhetoric Departmentfor supporting the lecture and the publication of this issue. PREFACE The goal of this series is to foster schol- arship on campus by providing new faculty members with the opportunity to share their research interest with their colleagues and students. We see the role of an academic li- brary not only as a place where bibliographic materials are acquired, stored, and made ac- cessible to the intellectual community, but also as an institution that is an active partici- pant in the generation of knowledge. New faculty members represent areas of scholarship the University wishes to develop or further strengthen.