Commitment to Reducing Inequality (CRI) Index 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speech by Andy Haldane at the Bank of Estonia, Tallinn, on Wednesday

Folk Wisdom Speech given by Andrew G Haldane Chief Economist Bank of England 100th Anniversary of the Bank of Estonia Tallinn, Estonia 19 September 2018 The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the Bank of England or the Monetary Policy Committee. I would like to thank Shiv Chowla, John Lewis, Jack Meaning and Sophie Stone for their help in preparing the text and to Nicholas Gruen and Matthew Taylor for discussions on these issues. I would like to thank David Bholat, Ben Broadbent, Janine Collier, Laura Daniels, Jonathan Fullwood, Andrew Hebden, Paul Lowe, Clare Macallan and Becky Maule and for their comments and contributions. 1 All speeches are available online at www.bankofengland.co.uk/speeches I am delighted to be here to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Bank of Estonia. It is a particular privilege to be giving this lecture in the Bank’s “Independence Hall” – the very spot where, on 24 February 1918, Estonia’s Provisional Government was formed. The founding of the Bank of Estonia followed on the Republic’s first birthday in 1919. Reaching your first century is a true milestone for any person or institution. In the UK, when you reach your 100th birthday you receive a signed card of congratulations from the Queen. I am afraid I have no royal birthday card for you today. But I have the next best thing – another speech from another central banker. Times are tough in central banking. Central banks have borne much of the burden of supporting the global economy as it has recovered from the global financial crisis. -

Pharma Report Exec 100518

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Prescription for Poverty Drug companies as tax dodgers, price gougers, and influence peddlers SEPTEMBER 2018 Background New Oxfam research shows that four pharmaceutical corporations—Abbott, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Pfizer—systematically stash their profits in overseas tax havens. They appear to deprive developing countries of more than $100 million every year—money that is urgently needed to meet the health needs of people in these countries—while vastly overcharging for their products. And these corporations deploy massive influencing operations to rig the rules in their favor and give their damaging behavior a veneer of legitimacy. Tax dodging, high prices, and influence peddling by drug companies exacerbate the yawning gap between rich and poor, between men and women, and between advanced economies and developing ones. Cover image: Sushmita (left, now 13 and shown here with her mother) was 3 when she got Japanese encephalitis, a mosquito-borne disease, in India’s northern Gorakhpur province. Sushmita was lucky, she survived. But she can't walk properly and has partly lost use of her hands, making it very difficult for her to write. She wants to do well in school, but struggles to keep up. Japanese encephalitis is endemic in this area of India. Poor public health conditions, lack of safe drinking water and proper sanitation, and few health facilities put young children in danger of Japanese encephalitis and other preventable diseases. More than 1,300 children died at the one hospital in the area in 2017, 69 of them in the course of four days when the hospital failed to pay its bill for oxygen the children needed to survive. -

Pricing Farmers out of Cotton: the Costs of World

Oxfam Briefing Paper 99 Pricing Farmers out of Cotton: The costs of World Bank reforms in Mali With global trade talks stalled at the World Trade Organisation (WTO), rich-country cotton subsidies remain unabated, hurting poor cotton farmers. World Bank led reforms to privatise the Malian cotton sector, including the adoption of a new price- setting mechanism, are further exacerbating the dire conditions in cotton-producing communities. A minimum level of price stability is vital for income security in the cotton sector and to prevent further slides into poverty. The wider donor community should provide adequate funds to finance a cotton-sector support fund, as well as invest in rural extension services and sustain capacity building of farmers to enable them to maximise their returns from new market opportunities. Summary Mali is one of the world’s poorest countries, with over two-thirds of the population – mostly in rural areas – living on less than a dollar a day. Mali is also the second largest cotton producer in sub-Saharan Africa after Burkina Faso. Cotton production is generally heralded as a success story in much of West and Central Africa, providing a critical development strategy for poor African countries such as Mali and enabling both governments and farm households to access income. The World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the wider donor community have also recognised the importance of cotton in reducing poverty and supporting the country’s economy. However, in recent years, much of this success has been undermined by depressed and volatile cotton prices, partly as the result of unchecked US subsidies, and the downward trend of commodity prices. -

Introduction to Network Science & Visualisation

IFC – Bank Indonesia International Workshop and Seminar on “Big Data for Central Bank Policies / Building Pathways for Policy Making with Big Data” Bali, Indonesia, 23-26 July 2018 Introduction to network science & visualisation1 Kimmo Soramäki, Financial Network Analytics 1 This presentation was prepared for the meeting. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the BIS, the IFC or the central banks and other institutions represented at the meeting. FNA FNA Introduction to Network Science & Visualization I Dr. Kimmo Soramäki Founder & CEO, FNA www.fna.fi Agenda Network Science ● Introduction ● Key concepts Exposure Networks ● OTC Derivatives ● CCP Interconnectedness Correlation Networks ● Housing Bubble and Crisis ● US Presidential Election Network Science and Graphs Analytics Is already powering the best known AI applications Knowledge Social Product Economic Knowledge Payment Graph Graph Graph Graph Graph Graph Network Science and Graphs Analytics “Goldman Sachs takes a DIY approach to graph analytics” For enhanced compliance and fraud detection (www.TechTarget.com, Mar 2015). “PayPal relies on graph techniques to perform sophisticated fraud detection” Saving them more than $700 million and enabling them to perform predictive fraud analysis, according to the IDC (www.globalbankingandfinance.com, Jan 2016) "Network diagnostics .. may displace atomised metrics such as VaR” Regulators are increasing using network science for financial stability analysis. (Andy Haldane, Bank of England Executive -

Andrew Haldane: the Creative Economy

The Creative Economy Speech given by Andrew G Haldane Chief Economist Bank of England The Inaugural Glasgow School of Art Creative Engagement Lecture The Glasgow School of Art 22 November 2018 The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the Bank of England or the Monetary Policy Committee. I would like to thank Marilena Angeli and Shiv Chowla for their help in preparing the text. I would like to thank Philip Bond, Clare Macallan and Mette Nielson for their comments and contributions. 1 All speeches are available online at www.bankofengland.co.uk/speeches It is a great pleasure to be at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA). For over 170 years, the GSA has been one of the leading educational institutions in the creative arts in Europe. Today, the School continues to provide a conveyor belt of talent that is fuelling the rise in the creative industries, a sector growing rapidly and one where the UK can genuinely be said to be a world-leader. It is creativity, and its role in improving incomes in the economy and well-being in society, that I will discuss this evening. Now, there is a certain irony in me (a middle-aged career public servant) giving a lecture to you (staff and students at one of Europe’s creative hot-spots) about the determinants and benefits of creativity. Don’t worry, that irony is not lost on me. Nonetheless, I hope that by analysing creativity through an economic and historical lens we can learn something about its key ingredients. Developing those raw ingredients, and mixing them appropriately, has been crucial for social and economic progress over the course of history. -

Bosnia and Herzegovina and the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework

Bosnia and Herzegovina and the United Nations 2021- Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework 2025 A Partnership for Sustainable Development Declaration of commitment The authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and the United Nations (UN) are committed to working together to achieve priorities in BiH. These are expressed by: ` The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and selected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and targets1 as expressed in the emerging SDG Framework in BiH and domesticated SDG targets2; ` Future accession to the European Union, as expressed in the Action Plan for implementation of priorities from the European Commission Opinion and Analytical Report3; ` The Joint Socio-Economic Reforms (‘Reform Agenda’), 2019-20224; and ` The human rights commitments of BiH and other agreed international and regional development goals and treaty obligations5 and conventions. This Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (CF), adopted by the BiH Council of Ministers at its 22nd Session on 16 December 2020 and reconfrmed by the BiH Presidency at its 114th Extraordinary Session on 5 March 2021, will guide the work of authorities in BiH and the UN system until 2025. This framework builds on the successes of our past cooperation and it represents a joint commitment to work in close partnership for results as defned in this Cooperation Framework that will help all people in BiH to live longer, healthier and more prosperous and secure lives. In signing hereafter, the cooperating partners endorse this Cooperation Framework and underscore their joint commitments toward the achievement of its results. Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina United Nations Country Team H.E. Dr. Zoran Tegeltija Dr. -

Central African Republic

Human Development Report 2014 Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience Explanatory note on the 2014 Human Development Report composite indices Central African Republic HDI values and rank changes in the 2014 Human Development Report Introduction The 2014 Human Development Report (HDR) presents the 2014 Human Development Index (HDI) (values and ranks) for 187 countries and UN-recognized territories, along with the Inequality-adjusted HDI for 145 countries, the Gender Development Index for 148 countries, the Gender Inequality Index for 149 countries, and the Multidimensional Poverty Index for 91 countries. Country rankings and values of the annual Human Development Index (HDI) are kept under strict embargo until the global launch and worldwide electronic release of the Human Development Report. It is misleading to compare values and rankings with those of previously published reports, because of revisions and updates of the underlying data and adjustments to goalposts. Readers are advised to assess progress in HDI values by referring to table 2 (‘Human Development Index Trends’) in the Statistical Annex of the report. Table 2 is based on consistent indicators, methodology and time-series data and thus shows real changes in values and ranks over time, reflecting the actual progress countries have made. Small changes in values should be interpreted with caution as they may not be statistically significant due to sampling variation. Generally speaking, changes at the level of the third decimal place in any of the composite indices are considered insignificant. Unless otherwise specified in the source, tables use data available to the HDRO as of 15 November 2013. -

Faqs) About the Gender Inequality Index (GII

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Gender Inequality Index (GII) What is the Gender Inequality Index? The Gender Inequality Index is a composite measure reflecting inequality in achievements between women and men in three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market. It varies between zero (when women and men fare equally) and one (when men or women fare poorly compared to the other in all dimensions). The health dimension is measured by two indicators: maternal mortality ratio and the adolescent fertility rate. The empowerment dimension is also measured by two indicators: the share of parliamentary seats held by each sex and by secondary and higher education attainment levels. The labour dimension is measured by women’s participation in the work force. The Gender Inequality Index is designed to reveal the extent to which national achievements in these aspects of human development are eroded by gender inequality, and to provide empirical foundations for policy analysis and advocacy efforts. How is the GII calculated, and what are its main findings in terms of national and regional patterns of inequality? There is no country with perfect gender equality – hence all countries suffer some loss in their HDI achievement when gender inequality is taken into account, through use of the GII metric. The Gender Inequality Index is similar in method to the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) – see Technical Note 3 for details. It can be interpreted as a percentage loss to potential human development due to shortfalls in the dimensions included. Since the Gender Inequality Index includes different dimensions than the HDI, it cannot be interpreted as a loss in HDI itself. -

Speech by Andy Haldane at the Glasgow School of Art, Glasgow, On

The Creative Economy Speech given by Andrew G Haldane Chief Economist Bank of England The Inaugural Glasgow School of Art Creative Engagement Lecture The Glasgow School of Art 22 November 2018 The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the Bank of England or the Monetary Policy Committee. I would like to thank Marilena Angeli and Shiv Chowla for their help in preparing the text. I would like to thank Philip Bond, Clare Macallan and Mette Nielson for their comments and contributions. 1 All speeches are available online at www.bankofengland.co.uk/speeches It is a great pleasure to be at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA). For over 170 years, the GSA has been one of the leading educational institutions in the creative arts in Europe. Today, the School continues to provide a conveyor belt of talent that is fuelling the rise in the creative industries, a sector growing rapidly and one where the UK can genuinely be said to be a world-leader. It is creativity, and its role in improving incomes in the economy and well-being in society, that I will discuss this evening. Now, there is a certain irony in me (a middle-aged career public servant) giving a lecture to you (staff and students at one of Europe’s creative hot-spots) about the determinants and benefits of creativity. Don’t worry, that irony is not lost on me. Nonetheless, I hope that by analysing creativity through an economic and historical lens we can learn something about its key ingredients. Developing those raw ingredients, and mixing them appropriately, has been crucial for social and economic progress over the course of history. -

Printer-Friendly Version

Global Rights Index 2018 - Violations of trade union rights increase in Europe The results of the latest ITUC Global Rights Index 2018 are worrying. The global union confederation notes that the democratic space is shrinking across the world. Corporate greed is on the rise as protection of workers is weakened and corporations like Amazon believe they can get away with anything that stands in the way of making profits. The number of countries with arbitrary arrests and detention of workers increased from 44 in 2017 to 59 in 2018, and freedom of speech was constrained in 54 countries. The global federation notes that more countries seek to exclude workers from labour law – “from migrant workers, public sector employees to workers in platform businesses, with 65% of countries excluding whole categories of workers from labour law.” The report notes that In Europe, 58% of countries violated collective bargaining rights, and three quarters of countries violated the right to strike. Italy is one of the countries mentioned in which there is an increase of workers exposed to physical violence and threats. Kazakhstan and Turkey are among the ten worst countries for workers’ rights in 2018. Macedonia and Spain saw a worsening of their rankings with a rise in attacks on workers’ rights in law and practice. The Global Rights Index reports on annual survey of Violations of Trade Union Rights. It ranks 142 countries against 97 internationally recognised indicators to assess where workers’ rights are best protected in law and in practice. The report rates countries from one to five according to these indicators, with an overall score placing countries in rankings of one to five. -

Human Development Index (HDI)

Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene Briefing note for countries on the 2020 Human Development Report Chile Introduction This year marks the 30th Anniversary of the first Human Development Report and of the introduction of the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI was published to steer discussions about development progress away from GPD towards a measure that genuinely “counts” for people’s lives. Introduced by the Human Development Report Office (HDRO) thirty years ago to provide a simple measure of human progress – built around people’s freedoms to live the lives they want to - the HDI has gained popularity with its simple yet comprehensive formula that assesses a population’s average longevity, education, and income. Over the years, however, there has been a growing interest in providing a more comprehensive set of measurements that capture other critical dimensions of human development. To respond to this call, new measures of aspects of human development were introduced to complement the HDI and capture some of the “missing dimensions” of development such as poverty, inequality and gender gaps. Since 2010, HDRO has published the Inequality-adjusted HDI, which adjusts a nation’s HDI value for inequality within each of its components (life expectancy, education and income) and the Multidimensional Poverty Index that measures people’s deprivations directly. Similarly, HDRO’s efforts to measure gender inequalities began in the 1995 Human Development Report on gender, and recent reports have included two indices on gender, one accounting for differences between men and women in the HDI dimensions, the other a composite of inequalities in empowerment and well-being. -

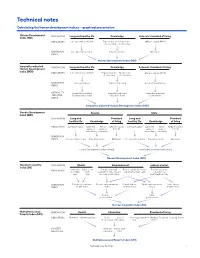

Technical Notes

Technical notes Calculating the human development indices—graphical presentation Human Development DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Index (HDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy index Education index GNI index INDEX Human Development Index (HDI) Inequality-adjusted DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Human Development Index (IHDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy Years of schooling Income/consumption INDEX INEQUALITY- Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted ADJUSTED life expectancy index education index income index INDEX Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) Gender Development Female Male Index (GDI) DIMENSIONS Long and Standard Long and Standard healthy life Knowledge of living healthy life Knowledge of living INDICATORS Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita years of years of (PPP $) years of years of (PPP $) schooling schooling schooling schooling DIMENSION INDEX Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Human Development Index (female) Human Development Index (male) Gender Development Index (GDI) Gender Inequality DIMENSIONS Health Empowerment Labour market Index (GII) INDICATORS Maternal Adolescent Female and male Female