Prehistoric and Historic Contexts for Albemarle County, Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VMI History Fact Sheet

VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE Founded in 1839, Virginia Military Institute is the nation’s first state-supported military college. U.S. News & World Report has ranked VMI among the nation’s top undergraduate public liberal arts colleges since 2001. For 2018, Money magazine ranked VMI 14th among the top 50 small colleges in the country. VMI is part of the state-supported system of higher education in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The governor appoints the Board of Visitors, the Institute’s governing body. The superintendent is the chief executive officer. WWW.VMI.EDU HISTORY OF VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE 540-464-7230 INSTITUTE OFFICERS On Nov. 11, 1839, 23 young Virginians were history. On May 15, 1863, the Corps of mustered into the service of the state and, in Cadets escorted Jackson’s remains to his Superintendent a falling snow, the first cadet sentry – John grave in Lexington. Just before the Battle of Gen. J.H. Binford Peay III B. Strange of Scottsville, Va. – took his post. Chancellorsville, in which he died, Jackson, U.S. Army (retired) Today the duty of walking guard duty is the after surveying the field and seeing so many oldest tradition of the Institute, a tradition VMI men around him in key positions, spoke Deputy Superintendent for experienced by every cadet. the oft-quoted words: “The Institute will be Academics and Dean of Faculty Col. J.T.L. Preston, a lawyer in Lexington heard from today.” Brig. Gen. Robert W. Moreschi and one of the founders of VMI, declared With the outbreak of the war, the Cadet Virginia Militia that the Institute’s unique program would Corps trained recruits for the Confederate Deputy Superintendent for produce “fair specimens of citizen-soldiers,” Army in Richmond. -

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

Georgetown's Historic Houses

VITUAL FIELD TRIPS – GEORGETOWN’S HISTORIC HOUSES Log Cabin This log cabin looks rather small and primitive to us today. But at the time it was built, it was really quite an advance for the gold‐seekers living in the area. The very first prospectors who arrived in the Georgetown region lived in tents. Then they built lean‐tos. Because of the Rocky Mountain's often harsh winters, the miners soon began to build cabins such as this one to protect themselves from the weather. Log cabin in Georgetown Photo: N/A More About This Topic Log cabins were a real advance for the miners. Still, few have survived into the 20th century. This cabin, which is on the banks of Clear Creek, is an exception. This cabin actually has several refinements. These include a second‐story, glass windows, and interior trim. Perhaps these things were the reasons this cabin has survived. It is not known exactly when the cabin was built. But clues suggest it was built before 1870. Historic Georgetown is now restoring the cabin. The Tucker‐Rutherford House James and Albert Tucker were brothers. They ran a grocery and mercantile business in Georgetown. It appears that they built this house in the 1870s or 1880s. Rather than living the house themselves, they rented it to miners and mill workers. Such workers usually moved more often than more well‐to‐do people. They also often rented the places where they lived. When this house was built, it had only two rooms. Another room was added in the 1890s. -

Virginia Horse Shows Association, Inc

2 VIRGINIA HORSE SHOWS ASSOCIATION, INC. OFFICERS Walter J. Lee………………………………President Oliver Brown… …………………….Vice President Wendy Mathews…...…….……………....Treasurer Nancy Peterson……..…………………….Secretary Angela Mauck………...…….....Executive Secretary MAILING ADDRESS 400 Rosedale Court, Suite 100 ~ Warrenton, Virginia 20186 (540) 349-0910 ~ Fax: (540) 349-0094 Website: www.vhsa.com E-mail: [email protected] 3 VHSA Official Sponsors Thank you to our Official Sponsors for their continued support of the Virginia Horse Shows Association www.mjhorsetransportation.com www.antares-sellier.com www.theclotheshorse.com www.platinumjumps.com www.equijet.com www.werideemo.com www.LMBoots.com www.vhib.org 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Officers ..................................................................................3 Official Sponsors ...................................................................4 Dedication Page .....................................................................7 Memorial Pages .............................................................. 8~18 President’s Page ..................................................................19 Board of Directors ...............................................................20 Committees ................................................................... 24~35 2021 Regular Program Horse Show Calendar ............. 40~43 2021 Associate Program Horse Show Calendar .......... 46~60 VHSA Special Awards .................................................. 63-65 VHSA Award Photos .................................................. -

A* ACE Study, See Student Body

UVA CLIPPINGS FILE SUBJECT HEADINGS *A* Anderson, John F. Angress, Ruth K, A.C.E. Study, see Student body – Characteristics Anthropology and Sociology, Dept. of A.I.D.S. Archaeology Abbott, Charles Cortez Abbott, Francis Harris Archer, Vincent Architecture - U.Va. and environs, see also Local History File Abernathy, Thomas P. Architecture, School of Abraham, Henry J. Art Department Academic costume, procession, etc. Arts and Sciences - College Academical Village, see Residential Colleges Arts and Sciences - Graduate School Accreditation, see also Self Study Asbestos removal, see Waste Accuracy in Academia Adams (Henry) Papers Asian Studies Assembly of Professors Administration and administrative Astronomy Department committees (current) Athletics [including Intramurals] Administration - Chart - Academic Standards, scholarships, etc. Admissions and enrollment – to 1970\ - Baseball - 1970-1979 - Basketball - 1980- - Coaches - In-state vs. out-of-state - Fee - S.A.T. scores see also Athletes - Academic standards - Football - Funding Blacks - Admission and enrollment - Intercollegiate aspects Expansion - Soccer Women- Admission to UVA - Student perceptions Aerospace engineering, see Engineering, Aerospace see also names of coaches Affirmative Action, Office of Afro-American, Atomic energy, see Engineering, Nuclear see Blacks - Afro-American… Attinger, Ernst O. AIDS, see A.I.D.S. Authors Alcohol, see also Institute/ Substance Abuse Studies Alden, Harold Automobiles Aviation Alderman Library, see Library, Alderman Awards, Honors, Prizes - Directory Alderman, Edwin Anderson – Biography - Obituaries *B* - Speeches, papers, etc. Alderman Press Baccalaureate sermons, 1900-1953 Alford, Neill H., Jr. Bad Check Committee Alumni activities Baker, Houston A., Jr. Alumni Association – local chapter Bakhtiar, James A.H. Alumni – noteworthy Balch lectures and awards American Assn of University Professors, Balfour addition, see McIntire School of Commerce Virginia chapter Ballet Amphitheater| Balz, A.G.A. -

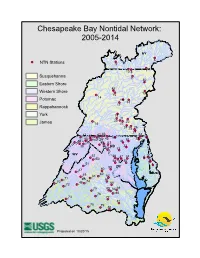

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014 NY 6 NTN Stations 9 7 10 8 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 Western Shore 12 15 14 Potomac 16 13 17 Rappahannock York 19 21 20 23 James 18 22 24 25 26 27 41 43 84 37 86 5 55 29 85 40 42 45 30 28 36 39 44 53 31 38 46 MD 32 54 33 WV 52 56 87 34 4 3 50 2 58 57 35 51 1 59 DC 47 60 62 DE 49 61 63 71 VA 67 70 48 74 68 72 75 65 64 69 76 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: All Stations NTN Stations 91 NY 6 NTN New Stations 9 10 8 7 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 12 Western Shore 92 15 16 Potomac 14 PA 13 Rappahannock 17 93 19 95 96 York 94 23 20 97 James 18 98 100 21 27 22 26 101 107 24 25 102 108 84 86 42 43 45 55 99 85 30 103 28 5 37 109 57 31 39 40 111 29 90 36 53 38 41 105 32 44 54 104 MD 106 WV 110 52 112 56 33 87 3 50 46 115 89 34 DC 4 51 2 59 58 114 47 60 35 1 DE 49 61 62 63 88 71 74 48 67 68 70 72 117 75 VA 64 69 116 76 65 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Table 1. -

The Institute Report

THE INSTITUTE REPORT Volume XVII October27,l989 Number 3 An occasional publication of the Public Information Office, Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia 24450. Tel (703) 464-7207. VMI to Celebrate 150th with Cake, Cannonade, and Convocation While its focus is clearly set on the 21st century, Events ofthe landmark year began last January VMI will spend the Nov. 10-12 weekend in celebration after several years of planning by a 17-member ofits 150th birthday and the accomplishments that VIRGINIA M1UTARY INSTITUTE Sesquicentennial Committee composed of Institute have marked the years since its opening on Nov. 11, wide representatives, including members ofthe Corps 1839. Hundreds ofalumni and special guests will joi n ofCadets. The committee has been headed by Col. intheculminating events ofthe sesquicentennial year. George M. Brooke, Jr., '36, of Lexington, emeritus The weekend program, which is listed in detail professor of history, with Col. Leonard L. Lewane, elsewhere is this publication, includes a three-day '50B, also of Lexington, as executive director of the schedule ofactivities beginning Friday, Nov. 10, with sesquicentennial office. burial of a time capsule, parade, and what promises The year-long anniversary events leading up to that evening to be a stirring and memorable concert. Founders Day November's grand finale have included special memorial observances; on Saturday will include the dedication ofthe new science hall; a con concerts; lectures; exhibits; a play; a leadership conference; several vocation; post-wide luncheons; and an afternoon football game. commemorative items, including a limited edition sesquicentennial Popular NBC weatherman Willard Scott has also been invited to medallion; and thepublication ofthree books. -

Palladio's Influence in America

Palladio’s Influence In America Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources 2008 marks the 500th anniversary of Palladio’s birth. We might ask why Americans should consider this to be a cause for celebration. Why should we be concerned about an Italian architect who lived so long ago and far away? As we shall see, however, this architect, whom the average American has never heard of, has had a profound impact on the architectural image of our country, even the city of Baltimore. But before we investigate his influence we should briefly explain what Palladio’s career involved. Palladio, of course, designed many outstanding buildings, but until the twentieth century few Americans ever saw any of Palladio’s works firsthand. From our standpoint, Palladio’s most important achievement was writing about architecture. His seminal publication, I Quattro Libri dell’ Architettura or The Four Books on Architecture, was perhaps the most influential treatise on architecture ever written. Much of the material in that work was the result of Palladio’s extensive study of the ruins of ancient Roman buildings. This effort was part of the Italian Renaissance movement: the rediscovery of the civilization of ancient Rome—its arts, literature, science, and architecture. Palladio was by no means the only architect of his time to undertake such a study and produce a publication about it. Nevertheless, Palladio’s drawings and text were far more engaging, comprehendible, informative, and useful than similar efforts by contemporaries. As with most Renaissance-period architectural treatises, Palladio illustrated and described how to delineate and construct the five orders—the five principal types of ancient columns and their entablatures. -

Albemarle County in Virginia

^^m ITD ^ ^/-^7^ Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.arGhive.org/details/albemarlecountyiOOwood ALBEMARLE COUNTY IN VIIIGIMIA Giving some account of wHat it -was by nature, of \srHat it was made by man, and of some of tbe men wHo made it. By Rev. Edgar Woods " It is a solemn and to\acKing reflection, perpetually recurring. oy tHe -weaKness and insignificance of man, tHat -wKile His generations pass a-way into oblivion, -with all tKeir toils and ambitions, nature Holds on Her unvarying course, and pours out Her streams and rene-ws Her forests -witH undecaying activity, regardless of tHe fate of Her proud and perisHable Sovereign.**—^e/frey. E.NEW YORK .Lie LIBRARY rs526390 Copyright 1901 by Edgar Woods. • -• THE MicHiE Company, Printers, Charlottesville, Va. 1901. PREFACE. An examination of the records of the county for some in- formation, awakened curiosity in regard to its early settle- ment, and gradually led to a more extensive search. The fruits of this labor, it was thought, might be worthy of notice, and productive of pleasure, on a wider scale. There is a strong desire in most men to know who were their forefathers, whence they came, where they lived, and how they were occupied during their earthly sojourn. This desire is natural, apart from the requirements of business, or the promptings of vanity. The same inquisitiveness is felt in regard to places. Who first entered the farms that checker the surrounding landscape, cut down the forests that once covered it, and built the habitations scattered over its bosom? With the young, who are absorbed in the engagements of the present and the hopes of the future, this feeling may not act with much energy ; but as they advance in life, their thoughts turn back with growing persistency to the past, and they begin to start questions which perhaps there is no means of answering. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10.900 I OM6 No. 102*4018 (Rw. gee) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominatlng or requestlng determinations of eligibility for lndlvldual propertles or districts, See lnstructlons In Quldellnes . for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletln 16). Complete each Item by marking "xu In the appropriate box or by enterlng the requested information. Ifan item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, rnaterlals, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed In the instructions. For additional space use contlnuatlon sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name John Vowles House other nameslsite number 1111 and 1113 West Main Street a 2. Location street & number 1111 and 1113 West Main Street anotfor publication city, town Charlottesville uvicinity state Virginia code VA county Charlottesville code 540 zip code 22901 (city) 3. Classlficatlon Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property W private building(s) Contrlbutlng Noncontributing public-local district 3 buildings public-State site sites public-Federal structure structures object objects 3 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resource8 prevlously N /A listed In the National Register N/A 4. StatelFederal Agency Certlflcatlon -- As the designated authority under the ~atlonalHlstorlc Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that thls anomination request for determination of ellglbllity meets the documentation standards for registering propertles in the Natlonal Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60, In my opinlon, the property [;?meets adoes not meet the Natlonal Register criteria, See contlnuatlon sheet. -

Corridor Analysis for the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail in Northern Virginia

Corridor Analysis For The Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail In Northern Virginia June 2011 Acknowledgements The Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC) wishes to acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions to this report: Don Briggs, Superintendent of the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail for the National Park Service; Liz Cronauer, Fairfax County Park Authority; Mike DePue, Prince William Park Authority; Bill Ference, City of Leesburg Park Director; Yon Lambert, City of Alexandria Department of Transportation; Ursula Lemanski, Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program for the National Park Service; Mark Novak, Loudoun County Park Authority; Patti Pakkala, Prince William County Park Authority; Kate Rudacille, Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority; Jennifer Wampler, Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation; and Greg Weiler, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The report is an NVRC staff product, supported with funds provided through a cooperative agreement with the National Capital Region National Park Service. Any assessments, conclusions, or recommendations contained in this report represent the results of the NVRC staff’s technical investigation and do not represent policy positions of the Northern Virginia Regional Commission unless so stated in an adopted resolution of said Commission. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the jurisdictions, the National Park Service, or any of its sub agencies. Funding for this report was through a cooperative agreement with The National Park Service Report prepared by: Debbie Spiliotopoulos, Senior Environmental Planner Northern Virginia Regional Commission with assistance from Samantha Kinzer, Environmental Planner The Northern Virginia Regional Commission 3060 Williams Drive, Suite 510 Fairfax, VA 22031 703.642.0700 www.novaregion.org Page 2 Northern Virginia Regional Commission As of May 2011 Chairman Hon. -

Gothic Revival Outbuildings of Antebellum Charleston, South Carolina Erin Marie Mcnicholl Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints Master of Science in Historic Preservation Terminal Non-thesis final projects Projects 5-2010 Gothic Revival Outbuildings of Antebellum Charleston, South Carolina Erin Marie McNicholl Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/historic_pres Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation McNicholl, Erin Marie, "Gothic Revival Outbuildings of Antebellum Charleston, South Carolina" (2010). Master of Science in Historic Preservation Terminal Projects. 4. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/historic_pres/4 This Terminal Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Non-thesis final projects at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Science in Historic Preservation Terminal Projects by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOTHIC REVIVAL OUTBUILDNGS OF ANTEBELLUM CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA A Project Presented to the Graduate Schools of Clemson University/College of Charleston In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Historic Preservation by Erin Marie McNicholl May 2010 Accepted by: Ashley Robbins Wilson, Committee Chair Ralph Muldrow Barry Stiefel, PhD ABSTRACT The Gothic Revival was a movement of picturesque architecture that is found all over the United States on buildings built in the first half of the nineteenth century. In Antebellum Charleston people tended to cling to the classical styles of architecture even when the rest of the nation and Europe were enthusiastically embracing the different picturesque styles, such as Gothic Revival and Italianate. In the United States the Gothic Revival style can be found adorning buildings of every use.