Nonsolvable Polynomials with Field Discriminant 5A 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solving Cubic Polynomials

Solving Cubic Polynomials 1.1 The general solution to the quadratic equation There are four steps to finding the zeroes of a quadratic polynomial. 1. First divide by the leading term, making the polynomial monic. a 2. Then, given x2 + a x + a , substitute x = y − 1 to obtain an equation without the linear term. 1 0 2 (This is the \depressed" equation.) 3. Solve then for y as a square root. (Remember to use both signs of the square root.) a 4. Once this is done, recover x using the fact that x = y − 1 . 2 For example, let's solve 2x2 + 7x − 15 = 0: First, we divide both sides by 2 to create an equation with leading term equal to one: 7 15 x2 + x − = 0: 2 2 a 7 Then replace x by x = y − 1 = y − to obtain: 2 4 169 y2 = 16 Solve for y: 13 13 y = or − 4 4 Then, solving back for x, we have 3 x = or − 5: 2 This method is equivalent to \completing the square" and is the steps taken in developing the much- memorized quadratic formula. For example, if the original equation is our \high school quadratic" ax2 + bx + c = 0 then the first step creates the equation b c x2 + x + = 0: a a b We then write x = y − and obtain, after simplifying, 2a b2 − 4ac y2 − = 0 4a2 so that p b2 − 4ac y = ± 2a and so p b b2 − 4ac x = − ± : 2a 2a 1 The solutions to this quadratic depend heavily on the value of b2 − 4ac. -

Elements of Chapter 9: Nonlinear Systems Examples

Elements of Chapter 9: Nonlinear Systems To solve x0 = Ax, we use the ansatz that x(t) = eλtv. We found that λ is an eigenvalue of A, and v an associated eigenvector. We can also summarize the geometric behavior of the solutions by looking at a plot- However, there is an easier way to classify the stability of the origin (as an equilibrium), To find the eigenvalues, we compute the characteristic equation: p Tr(A) ± ∆ λ2 − Tr(A)λ + det(A) = 0 λ = 2 which depends on the discriminant ∆: • ∆ > 0: Real λ1; λ2. • ∆ < 0: Complex λ = a + ib • ∆ = 0: One eigenvalue. The type of solution depends on ∆, and in particular, where ∆ = 0: ∆ = 0 ) 0 = (Tr(A))2 − 4det(A) This is a parabola in the (Tr(A); det(A)) coordinate system, inside the parabola is where ∆ < 0 (complex roots), and outside the parabola is where ∆ > 0. We can then locate the position of our particular trace and determinant using the Poincar´eDiagram and it will tell us what the stability will be. Examples Given the system where x0 = Ax for each matrix A below, classify the origin using the Poincar´eDiagram: 1 −4 1. 4 −7 SOLUTION: Compute the trace, determinant and discriminant: Tr(A) = −6 Det(A) = −7 + 16 = 9 ∆ = 36 − 4 · 9 = 0 Therefore, we have a \degenerate sink" at the origin. 1 2 2. −5 −1 SOLUTION: Compute the trace, determinant and discriminant: Tr(A) = 0 Det(A) = −1 + 10 = 9 ∆ = 02 − 4 · 9 = −36 The origin is a center. 1 3. Given the system x0 = Ax where the matrix A depends on α, describe how the equilibrium solution changes depending on α (use the Poincar´e Diagram): 2 −5 (a) α −2 SOLUTION: The trace is 0, so that puts us on the \det(A)" axis. -

Polynomials and Quadratics

Higher hsn .uk.net Mathematics UNIT 2 OUTCOME 1 Polynomials and Quadratics Contents Polynomials and Quadratics 64 1 Quadratics 64 2 The Discriminant 66 3 Completing the Square 67 4 Sketching Parabolas 70 5 Determining the Equation of a Parabola 72 6 Solving Quadratic Inequalities 74 7 Intersections of Lines and Parabolas 76 8 Polynomials 77 9 Synthetic Division 78 10 Finding Unknown Coefficients 82 11 Finding Intersections of Curves 84 12 Determining the Equation of a Curve 86 13 Approximating Roots 88 HSN22100 This document was produced specially for the HSN.uk.net website, and we require that any copies or derivative works attribute the work to Higher Still Notes. For more details about the copyright on these notes, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/ Higher Mathematics Unit 2 – Polynomials and Quadratics OUTCOME 1 Polynomials and Quadratics 1 Quadratics A quadratic has the form ax2 + bx + c where a, b, and c are any real numbers, provided a ≠ 0 . You should already be familiar with the following. The graph of a quadratic is called a parabola . There are two possible shapes: concave up (if a > 0 ) concave down (if a < 0 ) This has a minimum This has a maximum turning point turning point To find the roots (i.e. solutions) of the quadratic equation ax2 + bx + c = 0, we can use: factorisation; completing the square (see Section 3); −b ± b2 − 4 ac the quadratic formula: x = (this is not given in the exam). 2a EXAMPLES 1. Find the roots of x2 −2 x − 3 = 0 . -

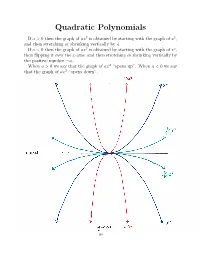

Quadratic Polynomials

Quadratic Polynomials If a>0thenthegraphofax2 is obtained by starting with the graph of x2, and then stretching or shrinking vertically by a. If a<0thenthegraphofax2 is obtained by starting with the graph of x2, then flipping it over the x-axis, and then stretching or shrinking vertically by the positive number a. When a>0wesaythatthegraphof− ax2 “opens up”. When a<0wesay that the graph of ax2 “opens down”. I Cit i-a x-ax~S ~12 *************‘s-aXiS —10.? 148 2 If a, c, d and a = 0, then the graph of a(x + c) 2 + d is obtained by If a, c, d R and a = 0, then the graph of a(x + c)2 + d is obtained by 2 R 6 2 shiftingIf a, c, the d ⇥ graphR and ofaax=⇤ 2 0,horizontally then the graph by c, and of a vertically(x + c) + byd dis. obtained (Remember by shiftingshifting the the⇥ graph graph of of axax⇤ 2 horizontallyhorizontally by by cc,, and and vertically vertically by by dd.. (Remember (Remember thatthatd>d>0meansmovingup,0meansmovingup,d<d<0meansmovingdown,0meansmovingdown,c>c>0meansmoving0meansmoving thatleft,andd>c<0meansmovingup,0meansmovingd<right0meansmovingdown,.) c>0meansmoving leftleft,and,andc<c<0meansmoving0meansmovingrightright.).) 2 If a =0,thegraphofafunctionf(x)=a(x + c) 2+ d is called a parabola. If a =0,thegraphofafunctionf(x)=a(x + c)2 + d is called a parabola. 6 2 TheIf a point=0,thegraphofafunction⇤ ( c, d) 2 is called thefvertex(x)=aof(x the+ c parabola.) + d is called a parabola. The point⇤ ( c, d) R2 is called the vertex of the parabola. -

The Determinant and the Discriminant

CHAPTER 2 The determinant and the discriminant In this chapter we discuss two indefinite quadratic forms: the determi- nant quadratic form det(a, b, c, d)=ad bc, − and the discriminant disc(a, b, c)=b2 4ac. − We will be interested in the integral representations of a given integer n by either of these, that is the set of solutions of the equations 4 ad bc = n, (a, b, c, d) Z − 2 and 2 3 b ac = n, (a, b, c) Z . − 2 For q either of these forms, we denote by Rq(n) the set of all such represen- tations. Consider the three basic questions of the previous chapter: (1) When is Rq(n) non-empty ? (2) If non-empty, how large Rq(n)is? (3) How is the set Rq(n) distributed as n varies ? In a suitable sense, a good portion of the answers to these question will be similar to the four and three square quadratic forms; but there will be major di↵erences coming from the fact that – det and disc are indefinite quadratic forms (have signature (2, 2) and (2, 1) over the reals), – det and disc admit isotropic vectors: there exist x Q4 (resp. Q3) such that det(x)=0(resp.disc(x) = 0). 2 1. Existence and number of representations by the determinant As the name suggest, determining Rdet(n) is equivalent to determining the integral 2 2 matrices of determinant n: ⇥ (n) ab Rdet(n) M (Z)= g = M2(Z), det(g)=n . ' 2 { cd 2 } ✓ ◆ n 0 Observe that the diagonal matrix a = has determinant n, and any 01 ✓ ◆ other matrix in the orbit SL2(Z).a is integral and has the same determinant. -

Nature of the Discriminant

Name: ___________________________ Date: ___________ Class Period: _____ Nature of the Discriminant Quadratic − b b 2 − 4ac x = b2 − 4ac Discriminant Formula 2a The discriminant predicts the “nature of the roots of a quadratic equation given that a, b, and c are rational numbers. It tells you the number of real roots/x-intercepts associated with a quadratic function. Value of the Example showing nature of roots of Graph indicating x-intercepts Discriminant b2 – 4ac ax2 + bx + c = 0 for y = ax2 + bx + c POSITIVE Not a perfect x2 – 2x – 7 = 0 2 b – 4ac > 0 square − (−2) (−2)2 − 4(1)(−7) x = 2(1) 2 32 2 4 2 x = = = 1 2 2 2 2 Discriminant: 32 There are two real roots. These roots are irrational. There are two x-intercepts. Perfect square x2 + 6x + 5 = 0 − 6 62 − 4(1)(5) x = 2(1) − 6 16 − 6 4 x = = = −1,−5 2 2 Discriminant: 16 There are two real roots. These roots are rational. There are two x-intercepts. ZERO b2 – 4ac = 0 x2 – 2x + 1 = 0 − (−2) (−2)2 − 4(1)(1) x = 2(1) 2 0 2 x = = = 1 2 2 Discriminant: 0 There is one real root (with a multiplicity of 2). This root is rational. There is one x-intercept. NEGATIVE b2 – 4ac < 0 x2 – 3x + 10 = 0 − (−3) (−3)2 − 4(1)(10) x = 2(1) 3 − 31 3 31 x = = i 2 2 2 Discriminant: -31 There are two complex/imaginary roots. There are no x-intercepts. Quadratic Formula and Discriminant Practice 1. -

Resultant and Discriminant of Polynomials

RESULTANT AND DISCRIMINANT OF POLYNOMIALS SVANTE JANSON Abstract. This is a collection of classical results about resultants and discriminants for polynomials, compiled mainly for my own use. All results are well-known 19th century mathematics, but I have not inves- tigated the history, and no references are given. 1. Resultant n m Definition 1.1. Let f(x) = anx + ··· + a0 and g(x) = bmx + ··· + b0 be two polynomials of degrees (at most) n and m, respectively, with coefficients in an arbitrary field F . Their resultant R(f; g) = Rn;m(f; g) is the element of F given by the determinant of the (m + n) × (m + n) Sylvester matrix Syl(f; g) = Syln;m(f; g) given by 0an an−1 an−2 ::: 0 0 0 1 B 0 an an−1 ::: 0 0 0 C B . C B . C B . C B C B 0 0 0 : : : a1 a0 0 C B C B 0 0 0 : : : a2 a1 a0C B C (1.1) Bbm bm−1 bm−2 ::: 0 0 0 C B C B 0 bm bm−1 ::: 0 0 0 C B . C B . C B C @ 0 0 0 : : : b1 b0 0 A 0 0 0 : : : b2 b1 b0 where the m first rows contain the coefficients an; an−1; : : : ; a0 of f shifted 0; 1; : : : ; m − 1 steps and padded with zeros, and the n last rows contain the coefficients bm; bm−1; : : : ; b0 of g shifted 0; 1; : : : ; n−1 steps and padded with zeros. In other words, the entry at (i; j) equals an+i−j if 1 ≤ i ≤ m and bi−j if m + 1 ≤ i ≤ m + n, with ai = 0 if i > n or i < 0 and bi = 0 if i > m or i < 0. -

Lyashko-Looijenga Morphisms and Submaximal Factorisations of A

LYASHKO-LOOIJENGA MORPHISMS AND SUBMAXIMAL FACTORIZATIONS OF A COXETER ELEMENT VIVIEN RIPOLL Abstract. When W is a finite reflection group, the noncrossing partition lattice NC(W ) of type W is a rich combinatorial object, extending the notion of noncrossing partitions of an n-gon. A formula (for which the only known proofs are case-by-case) expresses the number of multichains of a given length in NC(W ) as a generalized Fuß-Catalan number, depending on the invariant degrees of W . We describe how to understand some specifications of this formula in a case-free way, using an interpretation of the chains of NC(W ) as fibers of a Lyashko-Looijenga covering (LL), constructed from the geometry of the discriminant hypersurface of W . We study algebraically the map LL, describing the factorizations of its discriminant and its Jacobian. As byproducts, we generalize a formula stated by K. Saito for real reflection groups, and we deduce new enumeration formulas for certain factorizations of a Coxeter element of W . Introduction Complex reflection groups are a natural generalization of finite real reflection groups (that is, finite Coxeter groups realized in their geometric representation). In this article, we consider a well-generated complex reflection group W ; the precise definitions will be given in Sec. 1.1. The noncrossing partition lattice of type W , denoted NC(W ), is a particular subset of W , endowed with a partial order 4 called the absolute order (see definition below). When W is a Coxeter group of type A, NC(W ) is isomorphic to the poset of noncrossing partitions of a set, studied by Kreweras [Kre72]. -

Galois Groups of Cubics and Quartics (Not in Characteristic 2)

GALOIS GROUPS OF CUBICS AND QUARTICS (NOT IN CHARACTERISTIC 2) KEITH CONRAD We will describe a procedure for figuring out the Galois groups of separable irreducible polynomials in degrees 3 and 4 over fields not of characteristic 2. This does not include explicit formulas for the roots, i.e., we are not going to derive the classical cubic and quartic formulas. 1. Review Let K be a field and f(X) be a separable polynomial in K[X]. The Galois group of f(X) over K permutes the roots of f(X) in a splitting field, and labeling the roots as r1; : : : ; rn provides an embedding of the Galois group into Sn. We recall without proof two theorems about this embedding. Theorem 1.1. Let f(X) 2 K[X] be a separable polynomial of degree n. (a) If f(X) is irreducible in K[X] then its Galois group over K has order divisible by n. (b) The polynomial f(X) is irreducible in K[X] if and only if its Galois group over K is a transitive subgroup of Sn. Definition 1.2. If f(X) 2 K[X] factors in a splitting field as f(X) = c(X − r1) ··· (X − rn); the discriminant of f(X) is defined to be Y 2 disc f = (rj − ri) : i<j In degree 3 and 4, explicit formulas for discriminants of some monic polynomials are (1.1) disc(X3 + aX + b) = −4a3 − 27b2; disc(X4 + aX + b) = −27a4 + 256b3; disc(X4 + aX2 + b) = 16b(a2 − 4b)2: Theorem 1.3. -

Discriminants, Resultants, and Their Tropicalization

Discriminants, resultants, and their tropicalization Course by Bernd Sturmfels - Notes by Silvia Adduci 2006 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Newton polytopes and tropical varieties 3 2.1 Polytopes . 3 2.2 Newton polytope . 6 2.3 Term orders and initial monomials . 8 2.4 Tropical hypersurfaces and tropical varieties . 9 2.5 Computing tropical varieties . 12 2.5.1 Implementation in GFan ..................... 12 2.6 Valuations and Connectivity . 12 2.7 Tropicalization of linear spaces . 13 3 Discriminants & Resultants 14 3.1 Introduction . 14 3.2 The A-Discriminant . 16 3.3 Computing the A-discriminant . 17 3.4 Determinantal Varieties . 18 3.5 Elliptic Curves . 19 3.6 2 × 2 × 2-Hyperdeterminant . 20 3.7 2 × 2 × 2 × 2-Hyperdeterminant . 21 3.8 Ge’lfand, Kapranov, Zelevinsky . 21 1 4 Tropical Discriminants 22 4.1 Elliptic curves revisited . 23 4.2 Tropical Horn uniformization . 24 4.3 Recovering the Newton polytope . 25 4.4 Horn uniformization . 29 5 Tropical Implicitization 30 5.1 The problem of implicitization . 30 5.2 Tropical implicitization . 31 5.3 A simple test case: tropical implicitization of curves . 32 5.4 How about for d ≥ 2 unknowns? . 33 5.5 Tropical implicitization of plane curves . 34 6 References 35 2 1 Introduction The aim of this course is to introduce discriminants and resultants, in the sense of Gel’fand, Kapranov and Zelevinsky [6], with emphasis on the tropical approach which was developed by Dickenstein, Feichtner, and the lecturer [3]. This tropical approach in mathematics has gotten a lot of attention recently in combinatorics, algebraic geometry and related fields. -

Eisenstein and the Discriminant

Extra handout: The discriminant, and Eisenstein’s criterion for shifted polynomials Steven Charlton, Algebra Tutorials 2015–2016 http://maths.dur.ac.uk/users/steven.charlton/algebra2_1516/ Recall the Eisenstein criterion from Lecture 8: n Theorem (Eisenstein criterion). Let f(x) = anx + ··· + a1x + a0 ∈ Z[x] be a polynomial. Suppose there is a prime p ∈ Z such that • p | ai, for 0 ≤ i ≤ n − 1, • p - an, and 2 • p - a0. Then f(x) is irreducible in Q[x]. p−1 p−2 You showed the cyclotomic polynomial Φp(X) = x + x + ··· + x + 1 is irreducible by applying Eisenstein to the shift Φp(x + 1). Tutorial 2, Question 1 asks you to find a shift of x2 + x + 2, for which Eisenstein works. How can we tell what shifts to use, and what primes might work? We can use the discriminant of a polynomial. 1 Discriminant n The discriminant of a polynomial f(x) = anx + ··· + a1x + a0 ∈ C[x] is a number ∆(f), which gives some information about the nature of the roots of f. It can be defined as n 2n−2 Y 2 ∆(f) := an (ri − rj) , 1≤i<j≤n where ri are the roots of f(x). Example. 1) Consider the quadratic polynomial f(x) = ax2 + bx + c. The roots of this polynomial are √ 1 2 r1, r2 = a −b ± b − 4ac , √ 1 2 so r1 − r2 = a b − 4ac. We get that the discriminant is √ 2 2·2−2 1 2 2 ∆(f) = a a b − 4ac = b − 4ac , as you probably well know. 1 2) The discriminant of a cubic polynomial f(x) = ax3 + bx2 + cx + d is given by ∆(f) = b2c2 − 4ac3 − 4b3d − 27a2d2 + 18abcd . -

On Facets of the Newton Polytope for the Discriminant of the Polynomial System

On facets of the Newton polytope for the discriminant of the polynomial system Irina Antipova,∗ Ekaterina Kleshkova† Abstract We study normal directions to facets of the Newton polytope of the discriminant of the Laurent polynomial system via the tropical approach. We use the combinato- rial construction proposed by Dickenstein, Feichtner and Sturmfels for the tropical- ization of algebraic varieties admitting a parametrization by a linear map followed by a monomial map. Keywords: discriminant, Newton polytope, tropical variety, Bergman fan, matroid. 2020 Mathematical Subject Classification: 14M25, 14T15, 32S25. 1 Introduction Consider a system of n polynomial equations of the form X (i) λ Pi := aλ y = 0; i = 1; : : : ; n (1) λ2A(i) n (i) with unknowns y = (y1; : : : ; yn) 2 (C n 0) , variable complex coefficients a = (aλ ), where (i) n the sets A ⊂ Z are fixed, finite and contain the zero element 0, λ = (λ1; : : : ; λn), λ λ1 λn y = y1 · ::: · yn . Solution y(a) = (y1(a); : : : ; yn(a)) of (1) has a polyhomogeneity property, and thus the system usually can be written in a homogenized form by means of monomial transformations x = x(a) of coefficients (see [1]). To do this, it is necessary to distinguish a collection of n exponents !(i) 2 A(i) such that the matrix ! = !(1);:::;!(n) is non-degenerated. As a result, we obtain a reduced system of the form !(i) X (i) λ Qi := y + xλ y − 1 = 0; i = 1; : : : ; n; (2) arXiv:2107.04978v1 [math.AG] 11 Jul 2021 λ2Λ(i) (i) (i) (i) (i) where Λ := A n f! ; 0g and x = (xλ ) are variable complex coefficients.