Intra-Operative Trans-Ureteric Stent Insertion During Cytoreductive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodegradable Stent with Mtor Inhibitor-Eluting Reduces Progression of Ureteral Stricture

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Biodegradable Stent with mTOR Inhibitor-Eluting Reduces Progression of Ureteral Stricture Dong-Ru Ho 1,2,3 , Shih-Horng Su 4, Pey-Jium Chang 2, Wei-Yu Lin 1, Yun-Ching Huang 1, Jian-Hui Lin 1, Kuo-Tsai Huang 1, Wai-Nga Chan 1 and Chih-Shou Chen 1,* 1 Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi 613016, Taiwan; [email protected] (D.-R.H.); [email protected] (W.-Y.L.); [email protected] (Y.-C.H.); [email protected] (J.-H.L.); [email protected] (K.-T.H.); [email protected] (W.-N.C.) 2 Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan 333323, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 Department of Nursing, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Chiayi 613016, Taiwan 4 DuNing Incorperated, Tustin, CA 92780, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-975-353-211 Abstract: In this study, we investigated the effect of mTOR inhibitor (mTORi) drug-eluting biodegrad- able stent (DE stent), a putative restenosis-inhibiting device for coronary artery, on thermal-injury- related ureteral stricture in rabbits. In vitro evaluation confirmed the dose-dependent effect of mTORi, i.e., rapamycin, on fibrotic markers in ureteral component cell lines. Upper ureteral fibro- sis was induced by ureteral thermal injury in open surgery, which was followed by insertion of biodegradable stents, with or without rapamycin drug-eluting. Immunohistochemistry and Western blotting were performed 4 weeks after the operation to determine gross anatomy changes, collagen deposition, expression of epithelial–mesenchymal transition markers, including Smad, α-SMA, and Citation: Ho, D.-R.; Su, S.-H.; Chang, SNAI 1. -

Cystoscopy Insertion / Removal of Ureteric Stent

Tennyson Centre Darwin Private Hospital Suite 19 Suite 5 520 South Road Rocklands Drive Kurralta Park SA 5037 Tiwi NT 0810 P 08 8292 2399 P 08 8920 6212 F 08 8292 2388 F 08 8920 6213 [email protected] [email protected] www.urologicalsolutions.com.au www.urologicalsolutions.com.au CYSTOSCOPY INSERTION / REMOVAL OF URETERIC STENT Providing Specialist Care in South Australia & Northern Territory Associates: Dr Kym Horsell Dr Kim Pese Dr Michael Chong Dr Jason Lee Dr Alex Jay Dr Henry Duncan What is a Ureteric Stent? A ureteric stent is a specially designed hollow tube, made of a flexible plastic material that is placed in the ureter. The length of the stents used in adult patients varies between 22-30cm. 22-30cm long It is designed to stay in the urinary system by having both ends coiled; the top end coils in the kidney and the lower end coils inside the bladder to prevent its displacement. Stents are flexible enough to withstand various body movements. Stents are temporarily placed in the kidney to prevent or relieve obstruction. They allow urine to pass down the ureter, can help to relieve pain (e.g. from a stone/stone fragments), drain infection or help with kidney function if the kidney is obstructed. Having a stent in place will allow the ureter to heal. In the majority of patients, stents are required for only a short duration. This may be just a few days. However, a stent can stay in for up to three months without the need to replace it. -

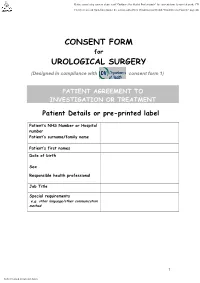

Stent Insertion Under General Anasthesia Patient Identifier/Label Statement of Patient

CONSENT FORM for UROLOGICAL SURGERY (Designed in compliance with consent form 1) PATIENT AGREEMENT TO INVESTIGATION OR TREATMENT Patient Details or pre-printed label Patient’s NHS Number or Hospital number Patient’s surname/family name Patient’s first names Date of birth Sex Responsible health professional Job Title Special requirements e.g. other language/other communication method 1 Patient identifier/label Name of proposed procedure ANAESTHETIC (Include brief explanation if medical term not clear) (Rigid ) CYSTOSCOPY AND STENT PROCEDURE SIDE……….. - GENERAL/REGIONAL THIS PROCEDURE INVOLVES TELESCOPIC INSPECTION OF BLADDER AND URETHRA AND - LOCAL INSERTING, REMOVING OR CHANGING A SOFT PLASTIC TUBE PLACED BETWEEN THE KIDNEY AND - SEDATION THE BLADDER. Statement of health professional (To be filled in by health professional with appropriate knowledge of proposed procedure, as specified in consent policy) I have explained the procedure to the patient. In particular, I have explained: The intended benefits TO DIAGNOSE AND TREAT ABNORMALITY OF THE URETERIC TUBE Serious or frequently occurring risks including any extra procedures, which may become necessary during the procedure. I have also discussed what the procedure is likely to involve, the benefits and risks of any available alternative treatments (including no treatment) and any particular concerns of this patient. Please tick the box once explained to patient COMMON MILD BURNING OR BLEEDING ON PASSING URINE FOR SHORT PERIOD AFTER OPERATION TEMPORARY INSERTION OF A CATHETER TEMPORARY -

Cystoscopy & Retrograde Pyelogram (&/-) Insertion Ureteric Stent

(Affix identification label here) 2018 URN: Cystoscopy & Retrograde Family name: Pyelogram +/- Insertion of Given name(s): Ureteric Stent Address: Date of birth: Sex: M F I Facility: A. Interpreter / cultural needs • Rarely damage to the urethra. A false passage may be produced causing leakage of urine or in the long term, a An Interpreter Service is required? Yes No narrowing that may affect flow of urine. If Yes, is a qualified Interpreter present? Yes No • Damage to the bladder by puncturing the bladder wall. This may need further surgery. A Cultural Support Person is required? Yes No © The State of Queensland (Queensland Health), Health), (Queensland Queensland of State The © • Swelling at the exit of the bladder which may stop If Yes, is a Cultural Support Person present? Yes No passage of urine. A tube (catheter) may need to be inserted to drain the urine until the swelling goes down. B. Condition and treatment • Bacteria may get into the blood stream with the The doctor has explained that you have the following development of septicaemia. Further treatment with condition: (Doctor to document in patient’s own words) antibiotics may be necessary. Permission to reproduce should be sought from [email protected] from sought be should reproduce to Permission • The tube may pass outside the ureter into the tissues. .......................................................................................................................................................................... This may need further surgery to remove and replace This condition requires the following procedure. (Doctor to the tube. document - include site and/or side where relevant to the • Bleeding which may stain the urine colour and procedure) sometimes cause blockage of urine flow. -

Minimally Invasive Management of Ureteral Strictures: a 5-Year

World Journal of Urology (2019) 37:1733–1738 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-018-2539-5 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Minimally invasive management of ureteral strictures: a 5‑year retrospective study C. Reus1 · M. Brehmer2 Received: 13 May 2018 / Accepted: 20 October 2018 / Published online: 30 October 2018 © The Author(s) 2018 Abstract Introduction Ureteric strictures are well-documented complications related to surgery or radiation therapy. Minimally invasive treatment using endoscopic dilatation or laser incision is the standard practice. There are no existing guidelines on which techniques to use in the treatment of diferent stricture types and a paucity of data regarding long-term results. Purpose Our study aimed to retrospectively assess the long-term efcacy of minimally invasive treatment in benign and malignant ureteric strictures. Materials and methods Over a 5-year period, 2007–2012, we analyzed the data of 59 consecutive patients undergoing mini- mally invasive treatment for symptomatic ureteric strictures. We excluded 16 patients from fnal analysis due to failed access or loss to follow-up. All patients but one were treated with antegrade, retrograde balloon or catheter dilatations. Successful outcome was defned as an asymptomatic, completely catheter free patient, with stable renal function. Results 43 patients were eligible for retrospective fnal analysis. The largest proportion of strictures occurred following surgery combined with radiotherapy 8/43 (19%). Preoperative decompression was required in 30/43 (70%). We identifed 32/43 (75%) balloon dilatations, 10/43 (23%) catheter dilatations and 1/43 (2%) laser incision. Overall success rate was 31/43 (72%). All 6 recurrences occurred within 36 months, 4 within the frst 12 months. -

Ureteric Injuries During Cancer Surgery Presentation and Management Over a 20-Year

International Surgery Journal Tohamy AZ et al. Int Surg J. 2021 Feb;8(2):593-599 http://www.ijsurgery.com pISSN 2349-3305 | eISSN 2349-2902 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2349-2902.isj20210370 Original Research Article Ureteric injuries during cancer surgery presentation and management over a 20-year Ali Zedan Tohamy1*, Haisam A. Samy2, Tark Salah3, Marwa T. Hussien4, Mohamed Hussein5 1Department of Surgical Oncology, 2Department of Diagnostic Radiology, 4Department of Pathology, South Egypt Cancer Institute, Egypt 3Department of Clinical Oncology, Assuit university, Egypt 5Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Faculty of medicine, Cairo University, Egypt Received: 01 January 2021 Revised: 13 January 2021 Accepted: 20 January 2021 *Correspondence: Dr. Ali Zedan Tohamy, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Background: Iatrogenic ureteral injury rare 0.3-1.5%. complication of abdominopelvic cancer surgery. We aimed to study the risk and management of ureteral injury among cancer patients. Methods: Diagnosis can be achieved retrograde pyelography, ureteroscopy, CT, or intravenous urography. Results: Years 2000 to 2020, 2904 patients in the Department of Surgical oncology, Assuit University, and 47 ureteral injury cases were identified. (1.62), 4/231 cervical cancer, 9/611 ovarian cancer and 7/462 endometrial cancer.,11/818 colon cancer,12/620 rectal cancer, 1/11 prostatic cancer, 3/151 retroperitoneal sarcoma. -

Stent Insertion.Pdf

Information about your procedure from The British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) This leaflet contains evidence-based information about your proposed urological procedure. We have consulted specialist surgeons during its preparation, so that it represents best practice in UK urology. You should use it in addition to any advice already given to you. To view the online version of this leaflet, type the text below into your web browser: http://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Ureteric stent insertion.pdf Key Points • Ureteric stents are normally used for obstruction (blockage) to one or both of your ureters (the tubes that carry urine from your kidneys to your bladder) • They are usually put in through your bladder using a telescope passed along your urethra (waterpipe) • Most stents are only needed for a short time but, in some patients, they stay for longer and need changing regularly • Significant stent irritation is seen in six out of ten patients (60%) and may result in early removal of the stent • Stent removal can usually be done under local anaesthetic using a small, flexible telescope What does this procedure involve? Ureteric stent procedures are normally carried out because of blockage to one or both of your ureters. The causes of the blockage may include: • a kidney stone (or stone fragment) – this can move into your ureter, either by itself or after treatment such as extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy • a stricture (narrowing) of the ureter – this can occur anywhere in the ureter for a number -

Ureteric Stent Insertion.Pdf

Information about your procedure from The British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) This leaflet contains evidence-based information about your proposed urological procedure. We have consulted specialist surgeons during its preparation, so that it represents best practice in UK urology. You should use it in addition to any advice already given to you. To view the online version of this leaflet, type the text below into your web browser: http://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Ureteric stent insertion.pdf Key Points • Ureteric stents are normally used for obstruction (blockage) to one or both of your ureters (the tubes that carry urine from your kidneys to your bladder) • They are put in through your bladder using a telescope passed along your urethra (waterpipe) • Most stents are only needed for a short time but, in some patients, they stay for longer and need changing regularly • Significant stent irritation is seen in six out of ten patients (60%) and may result in early removal of the stent • Stent removal can usually be done under local anaesthetic using a small, flexible telescope What does this procedure involve? Ureteric stent procedures are normally carried out because of blockage to one or both of your ureters. The causes of the blockage may include: • a kidney stone (or stone fragment) – this can move into your ureter, either by itself or after treatment such as extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy • a stricture (narrowing) of the ureter – this can occur anywhere in the ureter for a number of -

Ureteroscopy Kidney/Ureter Stone Removal

You have been booked for a Ureteroscopy Kidney/ureter Stone Removal 1 WHAT IS A URETEROSCOPY? Ureteroscpy is an examination or procedure using a ureteroscope. A ureteroscope is an instrument for examining the inside of the urinary tract. A ureteroscope is longer and thinner than a cystoscope and is used to see beyond the bladder, into the urteters, the tubes that carry urine from the kidney to the bladder. Some ureteroscopies are flexible like a thin, long straw (flexible uretersocope). Others are more rigid and firm (rigid uretroscope). Ureteroscopy is used to remove kidney or ureteric stones and/or to have a direct view of ureter and kidney to confirm or rule out malignancies. Rigid cystoscope and Flexible ureteroscope 2 Ureteroscopy is a routine procedure performed by urologists. The most common indication for ureteroscopy is to treat upper urinary tract calculi, particularly those that are either unsuitable for extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy or are refractory to that form of treatment. Other common indications include evaluation of an abnormal lesion revealed by less invasive imaging tools (eg, intravenous urography (IVU), MRI, CT scanning) or localisation of the source of positive urine culture or cytology results. Thus, ureteroscopy is often an essential part of the diagnostic algorithm and can also be used to treat the underlying disorder. 3 The reasons for a ureteroscopy include the following conditions: - Frequent urinary tract infections - Find the cause of symptoms such as blood in the urine (haematuria). - Unusual cells found in a urine sample, to confirm or rule out malignancies. - Urinary blockage caused by an abnormal narrowing to the ureter. -

Flexible Cystoscopy and Removal of Ureteric Stent

Flexible Cystoscopy and removal of Ureteric Stent What is flexible cystoscopy and removal of ureteric stent? You have had a stent placed within a ureter (tube connecting the kidney to the bladder) to allow urine to drain freely at a time when there was a blockage (often a stone). Once the blockage has cleared the stent will be removed. This is done using a flexible cystoscope (fine telescope) which is passed through the urethra (water pipe) into the bladder. A flexible cystoscopy is usually a quick procedure lasting approximately one to two minutes. Very often the patient is able to view the same images the practitioner sees via a screen. You may be given intravenous or oral antibiotics at the time of the procedure. On arrival you will either be seen by a nurse who will ask you for a brief medical history including any allergies or this information will be collected by the clinician doing the procedure. You may go to radiology for an X-ray prior to the stent removal. It is not necessary to change into a hospital gown for the procedure but you may do so if you prefer. Each patient is prepared with a wash of the urethral opening. A local anaesthetic gel is passed into the urethra and this also acts as a lubricant. The flexible cystoscope is inserted into the bladder via the urethra. During the procedure sterile water is passed via the cystoscope into the bladder. This process fills the bladder allowing the clinician to view the entire bladder and locate the stent. -

Having a Ureteroscopy and Stone Removal

Urology Procedures - Patient information Having a ureteroscopy and stone removal This leaflet has been designed to give you information about undergoing a ureteroscopy and answer some of the questions that you may have. If you have any further questions about the operation, please contact the nursing staff on 0118 322 7384 / 6546. What is a ureteroscopy? The urinary system is made up of the kidneys, ureter (the tube that links the kidney and bladder), bladder and urethra (the tube that urine passes through from the bladder before exiting the body). A ureteroscopy is a procedure that looks into the ureter and kidney. It involves inserting a special telescope, called a ureteroscope, into the urethra and then passing it through to the bladder and then on into the ureter and kidney. The operation is usually performed under general anaesthetic. This means that you are asleep during the procedure. There are risks associated with having a general anaesthetic, but they are small. The ureteroscope is about the thickness of a pencil and has a tiny camera on one end, so the doctor can view an image of your urinary system on a screen. It is usually used to help make a diagnosis, to see if a treatment has been successful, or to access the kidney or ureter to treat kidney stones. Why do I need a ureteroscopy? You may have been advised to have a ureteroscopy to try to find the cause of your symptoms. Sometimes, this will be clear from X-rays or tests of your blood or urine, but often the only way your doctor can be sure what is going on is to look inside your bladder and ureter. -

Patient Information Cystoscopy & Stent Procedure

Patient Information Department of Urology 15/Urol_04_11 Cystoscopy & stent procedure: procedure- specific information What is the evidence base for this information? This leaflet includes advice from consensus panels, the British Association of Urological Surgeons, the Department of Health and evidence-based sources; it is, therefore, a reflection of best practice in the UK. It is intended to supplement any advice you may already have been given by your GP or other healthcare professionals. Alternative treatments are outlined below and can be discussed in more detail with your Urologist or Specialist Nurse. What does the procedure involve? This procedure involves telescopic inspection of the bladder and urethra combined with insertion, removal or changing of a soft plastic tube placed between the kidney and the bladder. The procedure is usually performed under X-ray control What are the alternatives to this procedure? Observation, placement of a tube directly into the kidney through the back (nephrostomy), open surgical treatment. What should I expect before the procedure? You will usually be admitted on the same day as your surgery. You will normally receive an appointment for pre-assessment, approximately 14 days before your admission, to assess your general fitness, to screen for the carriage of MRSA and to perform some baseline investigations. After admission, you will be seen by members of the medical team which may include the Consultant, Specialist Registrar, House Officer and your named nurse. You will be asked not to eat or drink for 6 hours before surgery and, immediately before the operation, you may be given a pre-medication by the anaesthetist which will make you dry-mouthed and pleasantly sleepy.