Deathscapes in Diaspora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cathcart Heritage Trail.Pdf

TOURIST INTOR*VATION CATHCART: A VILLAGE IN THE CITY Cathcan is siruared on *re southem edee ot Gla-.ec* Visiton can rravel to rhe area bv can ..r bts or bv rarl The name Cathcan is thought to be derived from the 'caer' 'fort' 'cart' The trail starr at the Cor4'er In-sriruteLrbran. at rhe Celtic meaning and meaning a nofth end of Clarkton Roal. fenilising sffeam. Cathcart used to be a small villaee By Car: Clarkton Road r-.rhe 8?67. From the Crn on the banksof the White Can. Its history goesbaik Centre follou' sigr- tbr \{ounr Florida. Carhcan. to the times of King David I of Scotland (1124-1153\. Clarkton or Gitrrock'\{uirend. The king gave Cathcan to Walter Fitzalan, a loyal knight who was appointed Great Steward of Scotland. By Bus: Busesto Clarkton, Ca*rcan and \{uirend *'rll In his tum, Fitzalan, divided his lands amongsr often have routes using Clarkron Road. other knights and Renaldus was given Cathcart. The Cathcart By Rail: Trains on the Carhcan Circle leaveGlasgo*-'s lineage continued with Sir William de Ketkert who, in Central station frequentlv. The Coup'er Instirure and 1296, signedthe Ragman Roll thus swearingallegiance Library is a five minute l'alk trom rhe starion (unsuiml.le to Edward I, King of England. You will discover more - plartbrm|, to wheelchair users staircasear srarion about this noble militarv familv later. ourist Information Centre. Grearer Glasgow Toun-.t ' Board, 35/19 St. Vincent Place.GLASCO\I'Gl IER (-felephone: 041-204 4,100) ,) {/,<;r-rz,Ror:) -.>- r .. E.t'<._ -. -

Food Growing Strategy 2020 - 2025 DRAFT Information Contact Department

LET’S GROW TOGETHER Glasgow Food Growing Strategy 2020 - 2025 DRAFT information contact department... Contents Introduction 1.0 Our Vision • Achieving Our Vision • Strategic Context • National Strategies and policies • Local strategies and policies 2.0 Community Growing Options • Allotments • Community Gardens • Backcourts (and private gardens) • Stalled Spaces • School Grounds (or educational establishments in general) • Social Enterprises • Hospital Grounds • Housing Associations 3.0 What you said – Community Consultation 2015 to 2019 4.0 Increasing space for community growing and allotments • Allotment Sites • Community growing groups and spaces 5.0 How do I get started? • Finding land for growing • Getting permission to use a growing site • Who owns the land and do I need a lease? • Dealing with planning requirements • Getting community support or developing community group • Access to funding • Access to growing advice 6.0 How do I find out about community growing in my area? 7.0 Key Growing Themes / Opportunities Going Forward 8.0 Monitoring and Review 9.0 Next Steps / Action Plan 10.0 Appendices Appendix 1 – Food Growing Strategy Legislation Appendix 2 – Key Policies and Strategies Appendix 3 – Community Growing Matrix Appendix 4a – Food Growing Strategy Consultations Appendix 4b – Food Growing Strategy Appendix 4c – Allotments Consultation Appendix 5 – Help and Resources • Access to Land • Access to Community Support ■ Who can help you get your growing project off the ground ■ How do I set up my group • Access to funding • Funding Advice ■ Funding Guide • Access to Growing Advice ■ I want to grow fruit and vegetables – who can help me? ■ Lets Grow Glasgow Growing Guide Appendix 6 - Thanks Glasgow Food Growing Strategy 2020DRAFT Introduction I am delighted to introduce ..... -

Affordable Housing 4 Ath

FOR SALE Two Residential Development sites in Castlemilk, Glasgow ARDENCRAIG ROAD SITE MACHRIE ROAD SITE Ardencraig Road, Castlemilk, G45 9US Machrie Road, Castlemilk, Glasgow, G45 0AG • Residential development opportunities • Site areas of approximately 4.05 hectares (10.01 acres) and 5.79 hectares (14.31 acres) respectively • Key sites close to local amenities • The sites are being offered as a portfolio only 1 LOCATION Ardencraig Road site Machrie Road site LINN HAMPDEN PARK STADIUM KINGS PARK MACHRIE NCRAIG ROA E D D R ROAD SITE A ARDENCRAIG C R ROAD SITE O F T F O O T RO D DRIV A MILK E D A LE ST O CASTLEMILK CA R C HIGH SCHOOL A S MACHRIE G T I LEM A IL ROAD SITE A K R D R D R E IV C C R N E O GLASGOW CLUB D F N R A M TFO CASTLEMILK E IG A O T D R C R O H OA R AD R D A IE R O E A RIV K D D MIL TLE C AS A C ST L E M IL K D IVE R DR IV ILK E EM ASTL C The subject sites are situated approximately 5 miles south of the city centre within the There is good access to Castlemilk’s main bus routes, which provide connections to Castlemilk area of Glasgow. This area has seen the benefits of a regeneration strategy Glasgow city centre. There are also road links to the M77 and beyond to the M8 and which has improved local housing, amenities and the education estate. -

Cathcart House Sales Brochure

(F20878) - Cathcart House Brochure Digital Artwork.qxp_(F20878) - Cathcart Mill Brochure 07/03/2018 16:21 Page 1 CATHCART HOUSE GLASGOW An exclusive redevelopment of this landmark building forming Seventy Nine luxury apartments with allocated car parking space. COMING SOON (F20878) - Cathcart House Brochure Digital Artwork.qxp_(F20878) - Cathcart Mill Brochure 07/03/2018 16:21 Page 2 Introduction Cathcart House is an exclusive redevelopment of a landmark grade 'B' listed building and is situated in the sought-after south side of Glasgow close to transport links, with Cathcart and Mount Florida train stations providing quick & easy links into the city centre. The regeneration of Cathcart House, formerly the headquarters of Scottish Power, is to be carried out by The FM Group and will provide Seventy Nine luxury apartments with a mix of 1, 2 & 3 bedroom flats and 2 bedroom Penthouses. Train Stations approximately 10 minutes walk Glasgow City Centre 3.5 miles away Glasgow Airport 12 miles away Shops and amenities nearby (F20878) - Cathcart House Brochure Digital Artwork.qxp_(F20878) - Cathcart Mill Brochure 07/03/2018 16:21 Page 3 (F20878) - Cathcart House Brochure Digital Artwork.qxp_(F20878) - Cathcart Mill Brochure 07/03/2018 16:21 Page 4 Description Iconic Cathcart House being a Listed Building will retain its original entrance hallway showcasing its fantastic marble staircase with stunning decorative balustrades. The luxury apartments will be spread over five floors and will benefit from an attractive internal landscaped courtyard area. (F20878) - Cathcart House Brochure Digital Artwork.qxp_(F20878) - Cathcart Mill Brochure 07/03/2018 16:21 Page 5 The Building Cathcart House was designed by Sir John James Burnet, a Scottish Edwardian architect and built by the Wallace Scott Tailoring Institute in 1913 and extended 1919-22. -

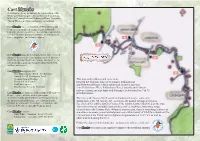

Cart Blanche Leaflet 6/10/02 12:42 Pm Page 1

Cart blanche Leaflet 6/10/02 12:42 pm Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Cart blanche is a voluntary group promoting the regeneration of the White Cart Water neighbourhoods between Pollok House in Pollok Country Park and Holmwood House, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson’s villa masterpiece in Cathcart. Cart blanche was constituted in 1999 to identify and connect communities along this highly urbanised four-mile stretch of waterway, also an important wildlife corridor for many plants and animals, including otters, foxes, kingfishers and Atlantic salmon. Cart blanche supports development that improves and enhances the amenity of this natural artery of the city’s southside and specifically encourages the creation of a riverbank linear park, providing facilities that favour walkers and cyclists. Cart blanche is supported by New Opportunities Fund - Fresh Futures Awards for All Community Fund Scottish Natural Heritage This four-mile walkway and cycle route Glasgow City Council between the National Trust for Scotland’s Pollok House Carts Greenspace and Holmwood House is fully signposted. It can be accessed The National Trust for Scotland. from Pollokshaws West, Pollokshaws East, Langside and Cathcart railway stations and also links with National Cycle routes Nos 7 & 75 Cart blanche meetings are held monthly at Holmwood at Pollok House. House - open to all who wish to participate. Activities include Guided Walks led by specialists in The river is the focus of local social and industrial history - some of it the natural and built heritage, also illustrated talks, dating back to the 7th century AD - as well as the natural heritage of the area. -

Glasgow Community Safety Index of Priority 2010/11 (Multi Member Wards) 0-15% Over Glasgow Average Below Glasgow Average

> 50% Glasgow Average 15-50% over Glasgow Average Glasgow Community Safety Index of Priority 2010/11 (Multi Member Wards) 0-15% over Glasgow Average Below Glasgow Average Risk Safe Theme Priority Outcome Indicators Anderston/City Calton North East (Glasgow) Govan Canal East Centre Hillhead Maryhill/Kelvin Southside Central Drumchapel/ Anniesland Garscadden/ Scotstounhill Springburn Greater Pollok Baillieston Craigton Partick West Langside Linn Shettleston Newlands/Auldburn Pollokshields Number of persons reported for drinking in public 561 454 244 293 220 76 53 179 189 112 70 96 85 74 77 112 137 112 46 60 32 Alcohol and Drugs Number of drug and alcohol related hospital admissions 283 618 213 529 327 298 42 71 125 183 188 134 320 219 326 101 69 157 58 108 46 Reported incidence of antisocial behaviour 286 156 117 146 106 97 143 130 145 108 99 92 85 84 94 98 79 96 65 79 84 Recorded crimes of vandalism, malicious mischief etc 195 157 160 155 131 106 124 128 125 121 95 92 107 118 106 74 64 121 80 65 98 Incidence of fire setting and fire related antisocial behaviour 296 391 698 278 374 177 110 221 73 384 174 96 310 220 164 47 39 108 112 21 80 Detection for the supply and possession with intent to supply Antisocial behaviour 493 346 306 332 270 350 135 207 151 151 125 102 115 88 130 124 84 39 34 50 58 controlled drugs In the past 12 months, have you been affected by antisocial 116 80 89 85 99 80 99 101 110 101 121 103 105 79 106 86 88 113 94 114 67 behaviour? (%Yes) Number of offences in relation to the possession of drugs 560 375 220 264 214 -

Castlemilk YC Community Sports Hub YOUR LOCAL COMMUNITY SPORTS HUB

Castlemilk YC Community Sports Hub YOUR LOCAL COMMUNITY SPORTS HUB www.castlemilkyouthcomplex.com [email protected] Castlemilk YC Sports and Activities Community Sports Hub As a local charity working in Castlemilk we continue to provide children and young Castlemilk Community Centre people with opportunities to help them recognise, raise and achieve their aspirations. 121 Castlemilk Drive, Glasgow, G45 9UG Tel: 0141 634 2233 The Community Sports Hub programme gives us scope to look at helping people www.glasgowlife.org.uk/communities/facilities/castlemilk-community-centre/ across the community become more active and live healthier lifestyles. KW Kickboxing Caroline Green Ages 4 – 16 years A big thank you to the many partners who helped make this sports and activity Open to all abilities directory as full and inclusive as possible, we hope this helps you and your family live Club School of Irish Contact: Karen Burns Monday 4 – 6pm a more active and healthier lifestyle. Dance 07590297068 Ages 4 – 16 years Tuesday 6.30 – 8pm We would always recommend contacting the coach or organisation before attending Contact: Tam Watt, 07847 Ages 3 – 16 years 568865, tamkfm@yahoo. Line Dancing any session. If you want to find out more or would like to get involved then please Open to all co.uk Wednesday 7 – 9pm contact [email protected] £6 per class Ages 16 + Contact: Caroline This an open class, some Glasgow Eagles 07784986119 or Michelle previous line dancing Table Tennis Club 07968698943, experience needed, both Monday 5 – 7pm caroline.parfery@btinternet. men and women welcome. com 1 8 16 + years. -

Flat 2/1, 427 Clarkston Road, Muirend

Flat 2/1, 427 Clarkston Road, Muirend www.nicolestateagents.co.uk Situation The area is well served by first class train and bus services to the City Centre (5 miles) and to East Kilbride, Muirend and its neighbouring suburbs of Shawlands, Langside and Giffnock which provide a broad range of excellent shopping facilities, supermarkets, fine restaurants, bars and numerous recreational facilities. Silverburn shopping centre provides an extensive range of shops, restaurants and supermarkets. There are a number of golf courses in the area and a selection of local health clubs. Pollok Country Park is also within easy reach. Linn Park is the second largest park in the city offering a wide variety of activities including an 18 hole golf course, children’s play area and its extensive grounds offer woodland and river walks. Holmwood House, situated within Linn Park was designed by one of Scotland’s greatest classical architects, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson (1817-1875) it is now maintained by the national Trust for Scotland and is open for the public to view, and can also be hired for events. The M77 provides commuter access to the City Centre, Glasgow Airport and along with the Southern Orbital provides an excellent connection to the Central Scotland motorway network as well as south towards Ayrshire and Prestwick Airport. Description Seldom available and beautifully presented one bedroom second floor flat, presented to the market in walk-in condition. The complete accommodation comprises: Well kept Communal entrance hallway and stairwell. Spacious reception hall with ample storage. Generous bay window sitting room/ dining room affording aspects over the surrounding area. -

Schools Ward Strategic Planning Area Learning

GLASGOW CITY COUNCIL EDUCATION SERVICES THIS IS A FORMAL CONSULTATIVE DOCUMENT Proposal to close Ardencraig Nursery School Strategic Learning Community Schools Ward Planning Area Ardencraig Nursery School (1) Linn South East Castlemilk St Martin’s Extended Day Centre Nursery (1) Linn South East Partnership Provider This document has been issued by Glasgow City Council for consultation in terms of the Schools (Consultation) (Scotland) Act 2010. The Ordnance Survey map data included within this document is provided by Glasgow City Council under licence from Ordnance Survey in order to fulfil its public function in relation to this public consultation. Persons viewing this mapping should contact Ordnance Survey Copyright for advice where they wish to licence Ordnance Survey mapping/data for their own use. 1 1. Background Information 1.1 On 12 September 2008, Glasgow City Council approved the Early Childhood and Extended Services Strategy 2008-2013. 1.2 The Strategy outlined the future vision for early childhood and extended services across Glasgow, and supported the Council’s commitment to improving access to childcare in the city which will enable more parents to access training and employment, as well as support parents already in employment. Included within the strategy and vision are the following key features: Within the next 5 years, to work towards parents being able to access childcare provision, 52 weeks a year, 8.00 a.m. until 6.00 p.m. and beyond where appropriate. All services to children and families, during the earliest years of a child’s life, are committed to ensuring that all children have the best possible start in life. -

GLASGOW 04.Indd

Local Government Boundary Commission for Scotland Fourth Statutory Review of Electoral Arrangements Glasgow City Council Area Report E06015 Report to Scottish Ministers August 2006 Local Government Boundary Commission for Scotland Fourth Statutory Review of Electoral Arrangements Glasgow City Council Area Constitution of the Commission Chairman: Mr John L Marjoribanks Deputy Chairman: Mr Brian Wilson OBE Commissioners: Professor Hugh M Begg Dr A Glen Mr K McDonald Mr R Millham Report Number E06015 August 2006 Glasgow City Council Area 1 Local Government Boundary Commission for Scotland 2 Glasgow City Council Area Fourth Statutory Review of Electoral Arrangements Contents Page Summary Page 7 Part 1 Background Pages 9 – 14 Paragraphs Origin of the Review 1 The Local Governance (Scotland) Act 2004 2 – 4 Commencement of the 2004 Act 5 Directions from Scottish Ministers 6 – 9 Announcement of our Review 10 – 16 General Issues 17 – 18 Defi nition of Electoral Ward Boundaries 19 – 24 Electorate Data used in the Review 25 – 26 Part 2 The Review in Glasgow City Council Area Pages 15 – 28 Paragraphs Meeting with Glasgow City Council 1 – 3 Concluded View of the Council 4 – 5 Aggregation of Existing Wards 6 – 9 Initial Proposals 10 – 14 Informing the Council of our Initial Proposals 15 – 16 Glasgow City Council Response 17 – 21 Consideration of the Council Response to the Initial Proposals 22 – 29 Provisional Proposals 30 – 34 Representations 35 Consideration of Representations 36 – 56 Part 3 Final Recommendation Pages 29 – 30 Appendices Pages 31 – -

Cathcart Walk 1 Link to Photo Album

Cathcart Walk 1 link to photo album Clarkston Road 1. Cathcart Trinity Church William Gardner Rowan, 1893-4, as Cathcart Free Church. Memorial stone laid 8 April 1893. B listed. 2. The Couper Institute. Funded by a bequest from Robert Couper of the local Millholm Paper Mills. Institute by James Sellars, 1887-8 (1887 datestone); new public library added to N by John Alfred Taylor Houston, 1923-4; Sellars' hall and library in range to S replaced by present hall, also by Houston. B listed. 3. Cathcart Station (former entrance/kiosk). Now a pub – The Beechings. Newlands Road 4. New Cathcart Church (former). John Bennie Wilson, 1907, as Cathcart UF Church; hall to left by John H Hamilton, 1899. Housing conversion completed 2006. B listed. 5. Weirs Pumps Headquarters (former). Pair of large, near identical ranges fronting Newlands Road with the entrance in recessed narrow link. The west range built 1912 to a design purchased from Albert Kahn’s Trussed Concrete Steel Co (USA): steel-framed, with concrete, multi-paned glazed infill panels, horizontal courses with classical mouldings. It is 4-storeys, with a setback 5th storey added by James Miller, 1928-9. Externally identical (minus 5th storey) east range built 1949-51. Facade only listed, as forms group with west range and amenity building. Wrought-iron gates with Art Nouveau ornament. Asymmetrical Amenity Block to east built 1937 by Wylie, Shanks and Wylie Architects. White-rendered with streamlining. B listed. Holmhead Place/Crescent 6. Traditional Victorian tenements with ‘wally close’ tiles. Built on the site of the Geddes Brothers Cathcart Carpet and Dye Works. -

152 Carmunnock Road, Cathcart

152 Carmunnock Road, Cathcart www.nicolestateagents.co.uk Situation The area is well served by first class train and bus services to the city centre and to East Kilbride. The neighbouring suburbs of Shawlands, Langside and Giffnock and Muirend provide a broad range of excellent shopping facilities, supermarkets, fine restaurants, bars and numerous recreational facilities. Silverburn shopping centre provides an extensive range of shops, restaurants and supermarkets. There are a number of golf courses in the area and a selection of local health clubs. Pollok Country Park is also within easy reach. Schooling is available locally at both primary and secondary level including St Fillan’s Primary School, OLA and Merrylee Primary. There are a number of pick up points in the South Side for Glasgow’s leading independent schools. Cathcart, located approximately five miles south of Glasgow City Centre, originated as a small village that grew up on the banks of the White Cart around Cathcart Castle in the area now known as Snuff Mill. The Conservation Area is centred on the Snuff Mill Bridge (c 1624) which spans the White Cart Water with Netherlee Road to the west and Holmhead Road to the north. It is dissected from north to south by the river and bounded on the south side through the centre line of the river as it bends along the northern part of Linn Park. Linn Park is the second largest park in the city and with its variety of activities including a golf course, children play areas and its extensive grounds offer woodland, river walks and Holmwood House, designed by one of Scotland’s greatest Classical architects, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson (1817-1875) and is now maintained by the National Trust for Scotland.