Authenticity of Yum Cha in Auckland, New Zealand, As Compared with Guangzhou, China, the Country of Origin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11566 Let's Yum Cha!

11566 Let’s Yum Cha! Yum cha, a term in Cantonese, literally meaning “drinking tea”, refers to the custom of eating small servings of different foods (dim sum) while sipping Chinese tea. It is an integral part of the culinary culture of Guangdong and Hong Kong. For Cantonese people, to yum cha is a tradition on weekend mornings, and whole families gather to chat and eat dim sum and drink Chinese tea. The tea is important, for it helps digest the foods. In the past, people went to a teahouse to yum cha, but dim sum restaurants have been gaining overwhelming popularity recently. Dim Sum literally means “touch your heart”, which consists of a wide spectrum of choices, including combinations of meat, seafood, vegetables, as well as desserts and fruit. Dim sum can be cooked, inter alia, by steaming and deep-frying. The various items are usually served in a small steamer basket or on a small plate. The serving sizes are usually small and normally served as three or four pieces in one dish. Because of the small portions, people can try a wide variety of food. Some well-known dim sums are: • Har gow: A delicate steamed dumpling with shrimp filling and thin (almost translucent) wheat starch skin. It is one of my favourite dim sum. • Siu mai: A small steamed dumpling with pork inside a thin wheat flour wrapper. It is usually topped off with crab roeand mushroom. • Char siu bau: A bun with Cantonese barbeque-flavoured pork and onions inside. It is probably the most famous dim sum around the world. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Happy Dining in the Valley Tennis Clinic TERM 2 There’S Much More Than Ding Dings and Horse Racing to Hong Kong’S 3 January to 1 April 2017 Cheeriest Vale

food WINTER CAMPS & CLINICS ENROLLING NOW AT www.esf.org.hk INSPIRING FUTURES Open to ESF Sports ESF & Non ESF Winter Camps & Clinics Students ENROL ONLINE WINTER CAMPS & CLINICS 13 - 30 December 2016 ESF Sports will host a number of sports camps Multi Sports Camp - starts at age 2! and clinics across Hong Kong. With access to Basketball Clinic Catch a tram to some of Hong Kong’s top gourmet stops. top quality facilities and our expert team of Football Clinic coaches, your child will have fun while developing Netball Clinic sporting abilities! Gymnastics Clinic Happy dining in the valley Tennis Clinic TERM 2 There’s much more than ding dings and horse racing to Hong Kong’s 3 January to 1 April 2017 cheeriest vale. Kate Farr & Rachel Read sniff out Happy Valley’s tastiest The role and power of sport in the development of young eateries. children cannot be overestimated. ESF Sports deliver a whole range of fun, challenging and structured sports programmes Dim sum delights like spring rolls, har gau and char siu bao Spice it up designed to foster a love of sport that will last a lifetime. If you prefer siu mai to scones with your come perfectly executed without a hint of Can you take the heat? The Michelin-starred afternoon tea, then Dim Sum, The Art of MSG, making them suitable for the whole Golden Valley sits on the first floor of The • Basketball • Multi Sports Chinese Tidbits is for you. It has been based family. The restaurant is open weekdays from Emperor Hotel and with its traditional decor • Football • Gymnastics in the same spot for nearly 25 years and 11am-11pm, or 10.30am-11pm at weekends and relaxed ambience, makes a pleasant • Netball • Kung Fu everything about this yum cha joint - from its (closed daily between 4.30 and 6pm), but we change of pace compare to the usual rowdy art deco-inspired interior to the long queues recommend swerving the scrum by dining Chinese banquet restaurants. -

Cuisines of Thailand, Korea and China

Journal of multidisciplinary academic tourism ISSN: 2645-9078 2019, 4 (2): 109 - 121 OLD ISSN: 2548-0847 www.jomat.org A General Overview on the Far East Cuisine: Cuisines of Thailand, Korea and China ** Sevgi Balıkçıoğlu Dedeoğlu*, Şule Aydın, Gökhan Onat ABSTRACT Keywords: Far east cuisine Thailand The aim of this study is to examine the Thai, Korean and Chinese cuisines of the Far East. Far Eastern Korea cuisine has a rich culinary culture that has hosted many civilizations that serve as a bridge between past China and present. Thai, Korean and Chinese cuisines are the most remarkable ones among the Far Eastern Ethnic Food cuisines. Therefore, these three cuisines have been the main focus of this study. In this study, cuisines’ history and their development are explained by giving basic information about these three countries. After this step, the general characteristics of the cuisines of these countries are mentioned. Finally, some of the foods that are prominent in these countries and identified with these countries are explained in Article History: general terms. Submitted: 04.06.2019 Accepted:07.12.2019 Doi: https://doi.org/10.31822/jomat.642619 1. Introduction With the reflection of postmodern consumption East can be highlighted in order to be able to mentality on tourist behavior, national cuisines attract them to these regions. As a matter of fact, have reached another level of importance as tourist the popularity of many cuisines from the Far East attractions. Despite the fact that local food has an regions is gradually increasing and they are important place in the past as a touristic product, becoming an attraction element. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Chinese Cuisine the Most Common Way to Greet People Is to Say

Chinese Cuisine The most common way to greet people is to say nǐ hǎo 你好! • 25% of the world’s population • 7% of world’s arable land 民以食为天 nǐ chi fan le ma? 你吃饭了吗? Chinese food can be divided into 8 regional cuisines 34 provincial regions Common features of Chinese food Colour, shape, aroma & taste 8 regional cuisines Peking duck Shanghai snack (scallion, wrap, sauce ) 8 regional cuisines Shandong Cuisine Stewed Meat Ball Lion's Head Meatballs Yellow River Carp in Sweet and Sour sauce 8 regional cuisines Sichuan Cuisine Hot Pot Sichuan cooks specialize in chilies and hot peppers and Sichuan dish is famous for aromatic and spicy sauces. 8 regional cuisines Sichuan Cuisine Kung Pao Chicken Mapo Dofu 8 regional cuisines Roasted Piglet Cantonese Cuisine Shark Fin Soup Steamed Sea Bass 8 regional cuisines Cantonese Cuisine Dim Sum Jiangsu 8 regional cuisines Cuisine Jiangsu Cuisine Fujian Stewed Crab with Clear Soup Cuisine Long-boiled and Dry-shredded Meat Duck Triplet Crystal Meat Buddha Jumping Squirrel with Mandarin Fish Over the Wall Liangxi Crisp Eel Snow Chicken 8 regional cuisines Hunan Cuisine Peppery and Hot Chicken 江西人不怕辣 四川人辣不怕 湖南人怕不辣 8 regional cuisines Anhui Cuisine Stewed Snapper; Huangshan Braised Pigeon Zhejiang Cuisine Sour West Lake Fish, Longjing Shelled Shrimp, Beggar's Chicken In general, southerners have a sweet tooth northerners crave salt Traditionally, one typical meal contains: Cold dishes (starter) Meat dishes Unlike British, Vegetables Chinese will invite Soup honorable guests Fish to dinner in Starch restaurants. Starter Meat dish 鸡 Ji Luck Chicken's feet are referred to As_______________phoenix feet. -

Chinese Cuisine from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia "Chinese Food

Chinese cuisine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "Chinese food" redirects here. For Chinese food in America, see American Chinese cuisine. For other uses, see Chinese food (disambiguation). Chao fan or Chinese fried rice ChineseDishLogo.png This article is part of the series Chinese cuisine Regional cuisines[show] Overseas cuisine[show] Religious cuisines[show] Ingredients and types of food[show] Preparation and cooking[show] See also[show] Portal icon China portal v t e Part of a series on the Culture of China Red disc centered on a white rectangle History People Languages Traditions[show] Mythology and folklore[show] Cuisine Festivals Religion[show] Art[show] Literature[show] Music and performing arts[show] Media[show] Sport[show] Monuments[show] Symbols[show] Organisations[show] Portal icon China portal v t e Chinese cuisine includes styles originating from the diverse regions of China, as well as from Chinese people in other parts of the world including most Asia nations. The history of Chinese cuisine in China stretches back for thousands of years and has changed from period to period and in each region according to climate, imperial fashions, and local preferences. Over time, techniques and ingredients from the cuisines of other cultures were integrated into the cuisine of the Chinese people due both to imperial expansion and from the trade with nearby regions in pre-modern times, and from Europe and the New World in the modern period. In addition, dairy is rarely—if ever—used in any recipes in the style. The "Eight Culinary Cuisines" of China[1] are Anhui, Cantonese, Fujian, Hunan, Jiangsu, Shandong, Sichuan, and Zhejiang cuisines.[2] The staple foods of Chinese cooking include rice, noodles, vegetables, and sauces and seasonings. -

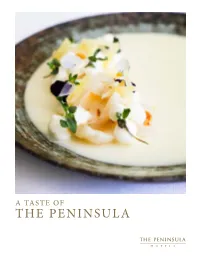

A Taste of the Peninsula Cookbook

A TASTE OF THE PENINSULA ABOUT THIS COOKBOOK Over the years, many visitors and guests have enjoyed TABLE OF CONTENTS the delicious cuisine and libations offered across The Peninsula Hotels, which is often missed once BREAKFAST they have returned home. This special collection Fluffy Egg-White Omelette – The Peninsula Tokyo 2 of signature recipes, selected by award-winning Peninsula chefs and mixologists, has been created with these guests in mind. SOUP Chilled Spring Lettuce Soup – The Peninsula Shanghai 4 These recipes aim to help The Peninsula guests recreate the moments and memories of their SALADS AND APPETISERS favourite Peninsula properties at home. The Stuffed Pepper and Mushroom Parmesan – The Peninsula Shanghai 6 collection includes light and healthy dishes from Heritage Grain Bowl – The Peninsula New York 7 The Lobby; rich, savoury Cantonese preparations Charred Caesar Salad – The Peninsula Beverly Hills 8 from one of The Peninsula Hotels’ Michelin-starred restaurants; and decadent pastries and desserts that evoke the cherished tradition of The Peninsula CHINESE DISHES Afternoon Tea. Cocktail recipes are also included, Barbecued Pork – The Peninsula Hong Kong 10 with which guests can revisit the flavours of Chive Dumplings – The Peninsula Shanghai 11 signature Peninsula tipples. Steamed Bean Curd with XO Sauce – The Peninsula Beijing 12 Summer Sichuan Chicken – The Peninsula Tokyo 13 By gathering these recipes, The Peninsula Hotels Fried Rice with Shrimp – The Peninsula Bangkok 14 aims to share a few of its closely guarded culinary -

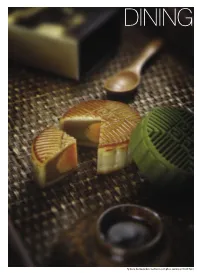

2009.09 P39-60 Dining.Indd

DINING DINING that’smags www.thebeijinger.com Septemberwww. 200 thatsbj.com9 / the Beijinger Sept. 200539 Fly me to the mooncakes. See Events, p41; photo courtesy of Grand Hyatt Take ining FANCY CAKES 5 21Cake 廿一客 These cute cubist creations use only fresh New Zealand cream, D Swiss chocolate and American hazelnuts in their search for confection perfection. Go retro with the Black Forest – fruity Kirsch-infused sponge and rich chocolate (RMB 168 for 15x15cm). Delivery only; order five hours in advance. Mon-Fri 7am-8pm, Sat-Sun 8am-6pm. Ste 1002, Bldg 9, Jianwai Soho, 39 Dongsanhuan Zhonglu, Chaoyang District (400 650 2121, [email protected]) www.21cake.com 朝阳区东三环中路39号建外Soho9号楼1002室 Bento & Berries 缤味美食屋 Michelangelo, da Vinci, Botticelli – surely they all would have appreciated the artistry inherent in B&B’s new cakes made from DINING Italian ice cream (RMB 85), available in chocolate, vanilla, green tea, mango and strawberry. Capital M(mmm) Mon-Fri 7am-11pm, Sat-Sun 7am-7pm. 1/F, Shangri-La’s Kerry Centre Hotel, 1 Guanghua This little piggy comes to Beijing. See below. Lu, Chaoyang District (6561 8833 ext 45) 朝阳区光华路1号嘉里中心饭店1层 an a plate of food be considered art? Spanish gastrono- Awfully Chocolate mist Ferran Adrià, head chef at “world’s best restaurant” A study in sweet simplicity, these cocoa-rich cakes come in a trio El Bulli, was controversially invited to exhibit his food at the C of flavors – plain chocolate (RMB 140), chocolate and banana Documenta art show in Germany a year or two back. He’s known (RMB 170) and chocolate, rum and cherry (RMB 180). -

Peer Reviewed Title: Critical Han Studies: the History, Representation, and Identity of China's Majority Author: Mullaney, Thoma

Peer Reviewed Title: Critical Han Studies: The History, Representation, and Identity of China's Majority Author: Mullaney, Thomas S. Leibold, James Gros, Stéphane Vanden Bussche, Eric Editor: Mullaney, Thomas S.; Leibold, James; Gros, Stéphane; Vanden Bussche, Eric Publication Date: 02-15-2012 Series: GAIA Books Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/07s1h1rf Keywords: Han, Critical race studies, Ethnicity, Identity Abstract: Addressing the problem of the ‘Han’ ethnos from a variety of relevant perspectives—historical, geographical, racial, political, literary, anthropological, and linguistic—Critical Han Studies offers a responsible, informative deconstruction of this monumental yet murky category. It is certain to have an enormous impact on the entire field of China studies.” Victor H. Mair, University of Pennsylvania “This deeply historical, multidisciplinary volume consistently and fruitfully employs insights from critical race and whiteness studies in a new arena. In doing so it illuminates brightly how and when ideas about race and ethnicity change in the service of shifting configurations of power.” David Roediger, author of How Race Survived U.S. History “A great book. By examining the social construction of hierarchy in China,Critical Han Studiessheds light on broad issues of cultural dominance and in-group favoritism.” Richard Delgado, author of Critical Race Theory: An Introduction “A powerful, probing account of the idea of the ‘Han Chinese’—that deceptive category which, like ‘American,’ is so often presented as a natural default, even though it really is of recent vintage. A feast for both Sinologists and comparativists everywhere.” Magnus Fiskesjö, Cornell University eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. -

Letter of Invitation

12th Congress of the Asian Society of Cardiovascular Imaging 2018 Letter of Invitation Dear Colleagues, We would like to cordially invite you to join the 12th Congress of Asian Society of Cardiovascular Imaging (ASCI) which is held in China National Convention Center in Beijing from August 16th to 18th, 2018 (Thurday to Saturday). Our theme is “Cardiac Imaging – the Belt and Road Invitation”. China National Convention Center is standing in the heart of Beijing Olympic Park and overlooking the beautiful ancient capital with easy access to the city center. Beijing was the capital in1045 BC and is considered the national political center, cultural center, international communication center, science and technology innovation center of China, with 7309 cultural relics, over 200 tourists attractions, beautiful gardens, and numerous other traditional culture and events. ASCI has grown dramatically in the past 11 years and now plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis, optimizing therapeutic decision making and improving outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease in Asia. The ASCI2018 Congress in Beijing will provide excellent opportunities for the education and scientific communication in the field of cardiovascular imaging among radiologists, cardiologists, technologist, researchers and individuals in the industry. We look forward to your participation and invite you to enjoy the ASCI2018 congress and the charms of Beijing with us. Prof. Zheng-yu Jin President-elect of Chinese Society of Radiology (CSR) Chairman of the Beijing Society of Radiology Professor and Chairman of the Department of Radiology, PUMC Hospital Beijing, China, 100730 Tel: 86-10-69155442 Fax: 86-10-69155441 E-mail: [email protected] 1 Welcome to China “Welcoming friends from afar gives one great delight.” ——Confucian Analects Whether you looking for the ancient history, urban wonders, cultural experience, and picturesque landscape, China is the best choice. -

Three Cases in China on Hakka Identity and Self-Perception

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Three cases in China on Hakka identity and self-perception Ricky Heggheim Master’s Thesis in Chinese Studie KIN 4592, 30 Sp Departement of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages University of Oslo 1 Summary Study of Hakka culture has been an academic field for only a century. Compare with many other studies on ethnic groups in China, Hakka study and research is still in her early childhood. This despite Hakka is one of the longest existing groups of people in China. Uncertainty within the ethnicity and origin of Hakka people are among the topics that will be discussed in the following chapters. This thesis intends to give an introduction in the nature and origin of Hakka identity and to figure out whether it can be concluded that Hakka identity is fluid and depending on situations and surroundings. In that case, when do the Hakka people consider themselves as Han Chinese and when do they consider themselves as Hakka? And what are the reasons for this fluidness? Three cases in China serve as the foundation for this text. By exploring three different areas where Hakka people are settled, I hope this text can shed a light on the reasons and nature of changes in identity for Hakka people and their ethnic consciousness as well as the diversities and sameness within Hakka people in various settings and environments Conclusions that are given here indicate that Hakka people in different regions do varies in large degree when it comes to consciousness of their ethnicity and background.