CLE Columbian Lawyers Association, First Judicial Department

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Boxing Association

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF AUGUST 2011 th th Based on results held from August 05 To August 29 , 2011 CHAIRMAN MEMBERS Edificio Ocean Business Plaza, Ave. JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] Aquilino de la Guardia con Calle 47, BARTOLOME TORRALBA (SPAIN) Oficina 1405, Piso 14 JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (A RGENTINA) Cdad. de Panamá, Panamá VICE CHAIRMAN ALAN KIM (KOREA) Phone: + (507) 340-6425 GEORG E MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.wbanews.com HEAVYWEIGHT (Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) CRUISERWEIGHT (200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) SUPER CHAMPION: WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO UKR World Champion: GUILLERMO JONES PAN World Cham pion: BEIBU T SHUMENOV KAZ World Champion: Won Title: 09- 27-08 Won Title: 01-29- 10 ALEXANDER POVETKIN RUS Last Mandatory: 10- 02-10 Last Mandatory: 07-23- 10 Won Title: 08-27-11 Last Defense: 10-02-10 Last Defense: 07-29-11 Last Mandatory: INTERIM CHAMPION: YOAN PABLO HERNANDEZ CUB Last Defense: IBF: STEVE CUNNINGHAM - WBO: MARCO HUCK WBC: BERNARD HOPKINS - IBF: TAVORIS CLOUD WBC: KRZYSZTOF WLODARCZYK WBC: VITALY KLITSCHKO - IBF:WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO WBO: NATHAN CLEVERLY WBO : WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO 1. HASIM RAHMAN USA 1. LATEEF KAYODE (NABA) NIG 1. GABRIEL CAMPILLO (OC) SPA 2. DAVID HAYE U.K. 2. PAWEL KOLODZIEJ (WBA INT) POL 2. GAYRAT AMEDOV (WB A INT) UZB 3. ROBERT HELENIUS (WBA I/C) FIN 3. OLA AFOLABI U.K. 3. DAWID KOSTECKY (WBA I/C) POL 4. ALEXANDER USTINO V (EBA) RUS 4. STEVE HERELIUS FRA 4. -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO JESUS MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of AUGUST Based on Results Held from 01St to August 31St, 2018

2018 Ocean Business Plaza Building, Av. Aquilino de la Guardia and 47 St., 14th Floor, Office 1405 Panama City, Panama Phone: +507 203-7681 www.wbaboxing.com WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO JESUS MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF AUGUST Based on results held from 01st to August 31st, 2018 CHAIRMAN VICE CHAIRMAN MIGUEL PRADO SANCHEZ - PANAMA GUSTAVO PADILLA - PANAMA [email protected] [email protected] The WBA President Gilberto Jesus Mendoza has been acting as interim MEMBERS ranking director for the compilation of this ranking. The current GEORGE MARTINEZ - CANADA director Miguel Prado is on a leave of absence for medical reasons. JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA - ARGENTINA MARIANA BORISOVA - BULGARIA Over 200 Lbs / 200 Lbs / 175 Lbs / HEAVYWEIGHT CRUISERWEIGHT LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT Over 90.71 Kgs 90.71 Kgs 79.38 Kgs WBA SUPER CHAMPION: ANTHONY JOSHUA GBR WBA SUPER CHAMPION: OLEKSANDR USYK UKR WORLD CHAMPION: MANUEL CHARR SYR CHAMPION IN RECESS: DENIS LEBEDEV RUS WORLD CHAMPION: DMITRY BIVOL RUS WBC: DEONTAY WILDER WORLD CHAMPION: BEIBUT SHUMENOV KAZ WBC: ADONIS STEVENSON IBF: ANTHONY JOSHUA WBO: ANTHONY JOSHUA WBC: OLEKSANDR USYK IBF: ARTUR BETERBIEV WBO: ELEIDER ALVAREZ 1. TREVOR BRYAN INTERIM CHAMP USA IBF: OLEKSANDR USYK WBO: OLEKSANDR USYK 1. BADOU JACK SWE 2. ALEXANDER POVETKIN I/C RUS 1. ARSEN GOULAMIRIAN INTERIM CHAMP ARM 2. MARCUS BROWNE USA 3. FRES OQUENDO PUR 2. MAKSIM VLASOV RUS 3. KARO MURAT ARM 4. JARRELL MILLER USA 3. KRZYSZTOF GLOWACKI POL 4. SULLIVAN BARRERA CUB 5. DILLIAN WHYTE JAM 4. MATEUSZ MASTERNAK POL 5. SHEFAT ISUFI SRB 6. DERECK CHISORA INT GBR 5. RUSLAN FAYFER RUS 6. -

SERGIO MARTINEZ (ARGENTINA) WON TITLE: September 15, 2012 LAST DEFENCE: April 27, 2013 LAST COMPULSORY : September 15, 2012 by Chavez

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL R A T I N G S JULY 2013 José Sulaimán Chagnon President VICEPRESITENTS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR TREASURER KOVID BHAKDIBHUMI, THAILAND CHARLES GILES, GREAT BRITAIN HOUCINE HOUICHI, TUNISIA MAURICIO SULAIMÁN, MEXICO JUAN SANCHEZ, USA REX WALKER, USA JU HWAN KIM, KOREA BOB LOGIST, BELGIUM LEGAL COUNSELORS EXECUTIVE LIFETIME HONORARY ROBERT LENHARDT, USA VICE PRESIDENTS Special Legal Councel to the Board of Governors JOHN ALLOTEI COFIE, GHANA of the WBC NEWTON CAMPOS, BRAZIL ALBERTO LEON, USA BERNARD RESTOUT, FRANCE BOBBY LEE, HAWAII YEWKOW HAYASHI, JAPAN Special Legal Councel to the Presidency of the WBC WORLD BOXING COUNCIL 2013 RATINGS JULY 2013 HEAVYWEIGHT +200 Lbs +90.71 Kgs VITALI KLITSCHKO (UKRAINE) WON TITLE: October 11, 2008 LAST DEFENCE: September 8, 2012 LAST COMPULSORY : September 10, 2011 WBA CHAMPION: Wladimir Klitschko Ukraine IBF CHAMPION: Wladimir Klitschko Ukraine WBO CHAMPION: Wladimir Klitschko Ukraine Contenders: WBC SILVER CHAMPION: Bermane Stiverne Canada WBC INT. CHAMPION: Seth Mitchell US 1 Bermane Stiverne (Canada) SILVER 2 Seth Mitchell (US) INTL 3 Chris Arreola (US) 4 Magomed Abdusalamov (Russia) USNBC 5 Tyson Fury (GB) 6 David Haye (GB) 7 Manuel Charr (Lebanon/Syria) INTL SILVER / MEDITERRANEAN/BALTIC 8 Kubrat Pulev (Bulgaria) EBU 9 Tomasz Adamek (Poland) 10 Johnathon Banks (US) 11 Fres Oquendo (P. Rico) 12 Franklin Lawrence (US) 13 Odlanier Solis (Cuba) 14 Eric Molina (US) NABF 15 Mark De Mori (Australia) 16 Luis Ortiz (Cuba) FECARBOX 17 Juan Carlos Gomez (Cuba) 18 Vyacheslav Glazkov (Ukraine) -

The Experience of the French Civil Code

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 20 Number 2 Article 3 Winter 1995 Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code Oliver Moreleau Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Oliver Moreleau, Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code, 20 N.C. J. INT'L L. 273 (1994). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol20/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This article is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol20/ iss2/3 Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code Olivier Moriteaut I. Introduction: The Civil Code as a Straight-Jacket? Since 1789, which marked the year of the French Revolution, France has known no fewer than thirteen constitutions.' This fact is scarcely evidence of political stability, although it is fair to say that the Constitution of 1958, of the Fifth Republic, has remained in force for over thirty-five years. On the other hand, the Civil Code (Code), which came into force in 1804, has remained substantially unchanged throughout this entire period. -

Use the Force? Understanding Force Majeure Clauses

Use the Force? Understanding Force Majeure Clauses J. Hunter Robinson† J. Christopher Selman†† Whitt Steineker††† Alexander G. Thrasher†††† Introduction It has been said that, sooner or later, everything old is new again.1 In the wake of the novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) sweeping the globe in 2020, a heretofore largely overlooked and even less understood nineteenth century legal term has come to the forefront of American jurisprudence: force majeure. Force majeure has become a topic du jour in the COVID-19 world with individuals and companies around the world seeking to excuse non- † B.S. (2011), Auburn University; J.D. (2014), Emory University School of Law. Hunter Robinson is an associate at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Hunter is a member of the firm’s litigation and banking and financial services practice groups and represents clients in commercial litigation matters across the country. †† B.S. (2007), Auburn University; J.D. (2012), University of South Carolina School of Law. Chris Selman is a partner at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Chris is a members of the firm’s construction and government contracts practice group. He has extensive experience advising clients at every stage of a construction project, managing the resolution of construction disputes domestically and internationally, and drafting and negotiating contracts for a variety of contractor and owner clients. ††† B.A. (2003), University of Alabama; J.D. (2008), Georgetown University Law Center. Whitt Steineker is a partner at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Whitt is a member of the firm’s litigation practice group, where he advises clients on a full range of services and routinely represents companies in complex commercial litigation. -

Interview With

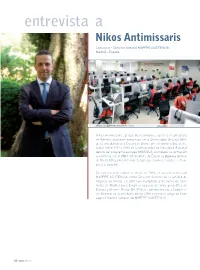

entrevista a Nikos Antimissaris Consejero – Director General MAPFRE ASISTENCIA Madrid – España Contact center de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA en China Nikos Antimissaris, griego de nacimiento, cursó la Licenciatura en Administración de Empresas en la Universidad de Lieja (Bél- gica), vinculándose a España el último año de universidad, al es- tudiar entre 1992 y 1993 en la Universidad de Valladolid (España) dentro del programa europeo ERASMUS. Completó su formación académica con el MBA del Instituto de Empresa Business School, de Madrid (España). Además del griego, domina el inglés, el fran- cés y el español. Su carrera profesional se inició en 1994 en su país natal con MAPFRE ASISTENCIA, como Director General de la Unidad de Negocio de Grecia. En 2001 fue trasladado a los Servicios Cen- trales en Madrid para dirigir el negocio del área geográfica de Europa y Oriente Medio. En 2004 fue promocionado a Subdirec- tor General de la entidad y desde 2006 ostenta el cargo de Con- sejero Director General de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA. 40 / 67 / 2013 667_trebol_esp.indd7_trebol_esp.indd 4040 007/11/137/11/13 001:581:58 “MAPFRE ASISTENCIA aporta una solución integral a sus socios aseguradores que incluye, no sólo la suscripción del riesgo (por la vía del reaseguro), sino también toda la infraestructura operativa para la tramitación de los siniestros y la prestación de los servicios.” Nikos Antimissaris habla siempre en primera persona del plural porque siente que alcanzar en 2013 un volumen de ingresos de mil cien millones de euros es una labor de los seis mil empleados de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA desde los cuarenta y cinco países en que está presente. -

Is COVID-19 an Act of God And/Or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi

ALERT Corporate Practice MAY 2020 Is COVID-19 an Act of God and/or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi This is the second in a series of alerts on Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses against failure to perform contracts. In our first alert, we discussed the elements of a force majeure clause and looked at how various states have interpreted force majeure clauses. We focused on how most states take a narrow view of these provisions and they adhere to the plain meaning of the force majeure provisions. This alert takes a look at one event often listed in force majeure clauses – Acts of God. As discussed in our previous alert, some courts will excuse performance of a contract only if the event causing the breach is actually listed in the force majeure clause. Among the list of events that would most likely excuse a failure to perform under a contract due to COVID-19 would be if the force majeure provision listed pandemics, epidemic, health emergencies or government orders or regulations. While your contract may not list these events, most force majeure provisions do include an Act of God. In this alert we look at whether it is likely that courts will find that COVID-19 is an Act of God and if such consideration will actually be a defense against performance of a contract. In general, courts have found that an Act of God is a natural event that would not occur by the intervention of man, but proceeds from physical causes. -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04Rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O. BOX 377 JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (ARGENTINA) MARACAY 2101 -A ALAN KIM (KOREA) EDO. ARAGUA - VENEZUELA SHIGERU KOJIMA (JAPAN) PHONE: + (58-244) 663-1584 VICE CHAIRMAN GONZALO LOPEZ SILVERO (USA) + (58-244) 663-3347 GEORGE MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORS FAX: + (58-244) 663-3177 E-mail: [email protected] SEBASTIAN CONTURSI (ARGENTINA) Web site: www.wbaonline.com UNIFIED CHAMPION: JEAN MARC MORMECK FRA World Champion: JOHN RUIZ USA Won Title: 04-02-05 World Champion: FABRICE TIOZZO FRA Won Title: 12-13 -03 Last Defense: Won Title: 03-20- 04 Last Mandatory: 04-30 -05 _________________________________ Last Mandatory: 02-26- 05 Last Defense: 04-30 -05 World C hampion: VACANT Last Defense: 02-26- 05 WBC: VITALI KLITSCHKO - IBF: CHRIS BYRD WBC: JEAN MARC MORMECK- IBF: O’NEIL BELL WBC: THOMAS ADAMEK - IBF: CLINTON WOODS WBO : LAMON BREWSTER WBO : JOHNNY NELSON WBO : ZSOLT ERDEI 1. NICOLAY VALUEV (OC) RUS 1. VALERY BRUDOV RUS 1. JORGE CASTRO (LAC) ARG 2. NOT RATED 2. VIRGIL HILL USA 2. SILVIO BRANCO (OC) ITA 3. WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO UKR 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 3. GUILLERMO JONES (0C) PAN 3. MANNY SIACA (LAC-INTERIM) P.R. ( Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 4. RAY AUSTIN (LAC) USA 4. STEVE CUNNINGHAM USA (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) 4. GLEN JOHNSON USA ( 5. CALVIN BROCK USA 5. LUIS PINEDA (LAC) PAN 5. PIETRO AURINO ITA l 6. -

Force Majeure and Climate Change: What Is the New Normal?

Force majeure and Climate Change: What is the new normal? Jocelyn L. Knoll and Shannon L. Bjorklund1 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................2 I. THE SCIENCE OF CLIMATE CHANGE ..................................................................................4 II. FORCE MAJEURE: HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT .........................................................8 III. FORCE MAJEURE IN CONTRACTS ...................................................................................11 A. Defining the Force Majeure Event. ..............................................................................12 B. Additional Contractual Requirements: External Causation, Unavoidability and Notice 15 C. Judicially-Imposed Requirements. ...............................................................................18 1. Foreseeability. .................................................................................................18 2. Ultimate (or external) causation.....................................................................21 D. The Effect of Successfully Invoking a Contractual Force Majeure Provision ............25 E. Force Majeure in the Absence of a Specific Contractual Provision. ...........................25 IV. FORCE MAJEURE PROVISIONS IN STANDARD FORM CONTRACTS AND MANDATORY PROVISIONS FOR GOVERNMENT CONTRACTS ......................................28 A. Standard Form Contracts .............................................................................................28 -

Consent Decree: United States Of

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA ATLANTA DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Civil Action No. 1:00-CV-3142 JTC v. ) ) CONSENT DECREE COLONIAL PIPELINE COMPANY, ) ) Defendant. ) ____________________________________) I. BACKGROUND A. Plaintiff, the United States of America (“United States”), through the Attorney General, at the request of the Administrator of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”), filed a civil complaint (“Complaint”) against Defendant, Colonial Pipeline Company (“Colonial”), pursuant to the Clean Water Act (“CWA”), 33 U.S.C. §§ 1251 et seq., seeking injunctive relief and civil penalties for the discharge of oil into navigable waters of the United States or onto adjoining shorelines. B. The Parties agree that it is desirable to resolve the claims for civil penalties and injunctive relief asserted in the Complaint without further litigation. C. This Consent Decree is entered into between the United States and Colonial for the purpose of settlement and it does not constitute an admission or finding of any violation of federal or state law. This Decree may not be used in any civil proceeding of any type as evidence or proof of any fact or as evidence of the violation of any law, rule, regulation, or Court decision, except in a proceeding to enforce the provisions of this Decree. D. To resolve Colonial’s civil liability for the claims asserted in the Complaint, Colonial will pay a total civil penalty of $34 million to the United States, comply with the injunctive relief requirements in this Consent Decree, and satisfy all other terms of this Consent Decree. -

Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses | a National Survey | Shook, Hardy & Bacon

2020 — Force Majeure SHOOK SHB.COM and Common Law Defenses A National Survey APRIL 2020 — Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses A National Survey Contractual force majeure provisions allocate risk of nonperformance due to events beyond the parties’ control. The occurrence of a force majeure event is akin to an affirmative defense to one’s obligations. This survey identifies issues to consider in light of controlling state law. Then we summarize the relevant law of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. 2020 — Shook Force Majeure Amy Cho Thomas J. Partner Dammrich, II 312.704.7744 Partner Task Force [email protected] 312.704.7721 [email protected] Bill Martucci Lynn Murray Dave Schoenfeld Tom Sullivan Norma Bennett Partner Partner Partner Partner Of Counsel 202.639.5640 312.704.7766 312.704.7723 215.575.3130 713.546.5649 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SHOOK SHB.COM Melissa Sonali Jeanne Janchar Kali Backer Erin Bolden Nott Davis Gunawardhana Of Counsel Associate Associate Of Counsel Of Counsel 816.559.2170 303.285.5303 312.704.7716 617.531.1673 202.639.5643 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] John Constance Bria Davis Erika Dirk Emily Pedersen Lischen Reeves Associate Associate Associate Associate Associate 816.559.2017 816.559.0397 312.704.7768 816.559.2662 816.559.2056 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Katelyn Romeo Jon Studer Ever Tápia Matt Williams Associate Associate Vergara Associate 215.575.3114 312.704.7736 Associate 415.544.1932 [email protected] [email protected] 816.559.2946 [email protected] [email protected] ATLANTA | BOSTON | CHICAGO | DENVER | HOUSTON | KANSAS CITY | LONDON | LOS ANGELES MIAMI | ORANGE COUNTY | PHILADELPHIA | SAN FRANCISCO | SEATTLE | TAMPA | WASHINGTON, D.C. -

World Boxing Association Gilberto Mendoza

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF APRIL 2 009 th TH Based on results held from April 9 , 2008 to May 14 , 2009 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN Edificio Ocean Business Plaza, Ave. BARTOLOME TORRALBA (SPAIN) JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] Aquilino de la Guardia con Calle 47, JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (ARGENTINA) Oficina 1405, Piso 14 VICE CHAIRMAN ALAN KIM (KOREA) Cdad. de Panamá, Panamá GONZALO LOPEZ SILVERO (USA) Phone: + (507) 340-6425 GEORGE MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORS E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.wbaonline.com SEBASTIAN CONTURSI (ARGENTINA) HEAV YWEIGHT (Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) CRUISERWEIGHT (200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) World Champion:RUSLAN CHAGAEV (*) UZB World Champion: GUILLERMO JONES PAN World Champion: HUGO H. GARAY ARG Won Title: 09-27-08 World Champion: NICOLAY VALUEV RUS Won Title: 07-03-08 Won Title: 08-30-08 Last Mandatory: Last Mandatory: 11-22-08 Last Mandatory: Last Defen se: Last Defense: 11-22-08 Last Defense: 12-20- 08 WBC:VITALY KLITSCHKO- IBF:WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO WBC:GIACOBBE FRAGOMENI- WBO: VICTOR RAMIREZ WBC: ADRIAN DIACONU - IBF: CHAD DAWSON WBO: WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO IBF: TOMASZ ADAMEK WBO: ZSOLT ERDEI 1. KALI MEEHAN AUS 1. VALERY BRUDOV (OC) RUS 1. JURGEN BRAHMER (EBU) GER 2. TARAS BIDENKO UKR 2. GRIGORY DROZD (PABA) RUS 2. VYACHESLAV UZELKOV (WBA I/C) UKR 3. JOHN RUIZ (OC) USA 3. FRANCISCO PALACIOS (LAC) P.R. 3. ALEKSY KUZIEMSKI (EBA) POL 4. KEVIN JOHNSON USA 4. FIRAT ARSLAN GER 4.